Photographs of Life at Two Edges of the North American Plate

For her book Rift/Fault, Marion Belanger investigated landscapes along the San Andreas Fault in California and the Mid-Atlantic Rift in Iceland.

Incredible geological forces move miles below our feet, yet few of us spend much time considering Earth’s tectonic plates and liquid mantle. Only when a volcano spits ash and lava or an earthquake rattles a city do we collectively remember. For those who live along the rifts and faults, however, that activity is harder to forget. Between 2006 and 2012, photographer Marion Belanger investigated the landscapes at two edges of the North American Plate: the San Andreas Fault in California and the Mid-Atlantic Rift in Iceland.

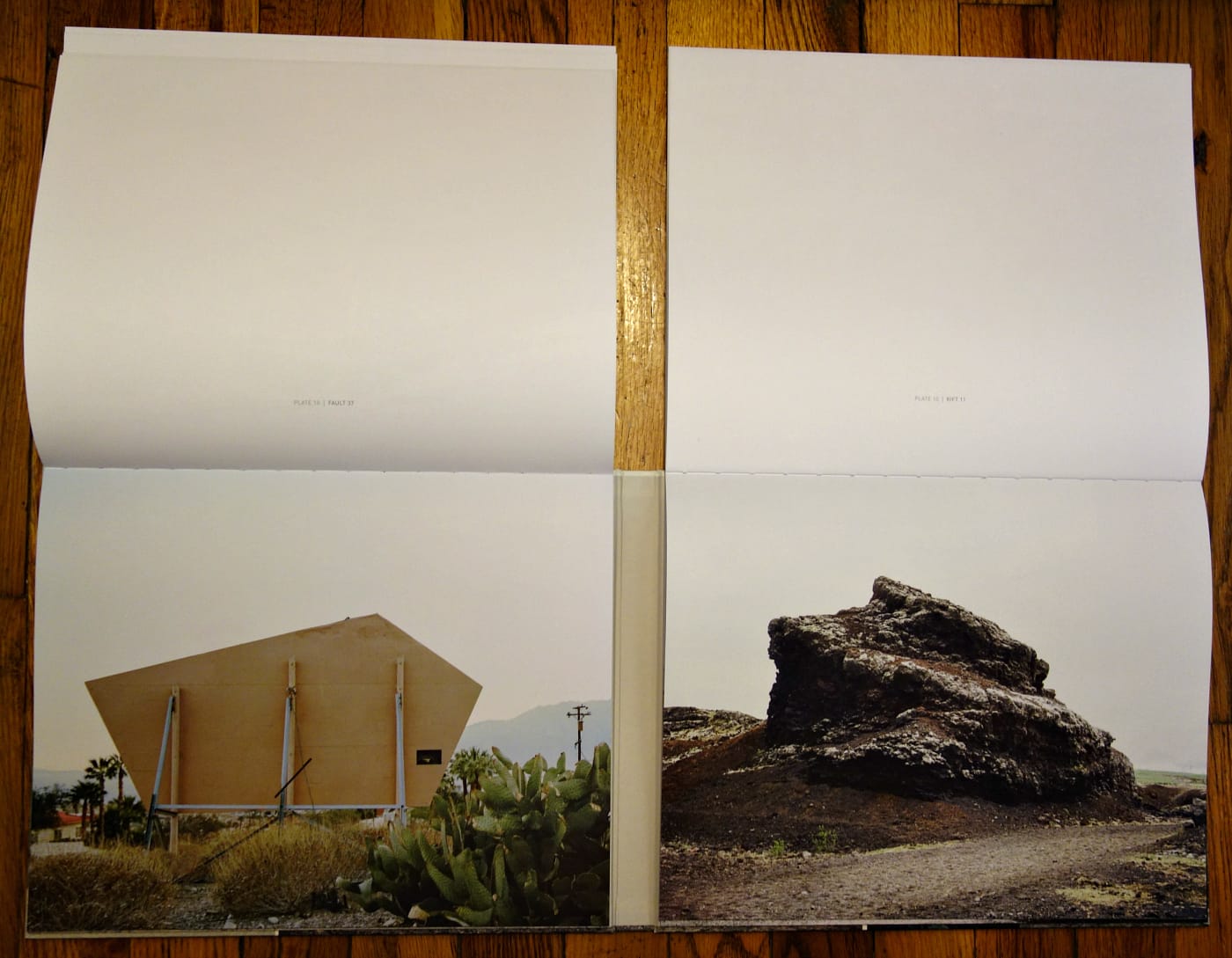

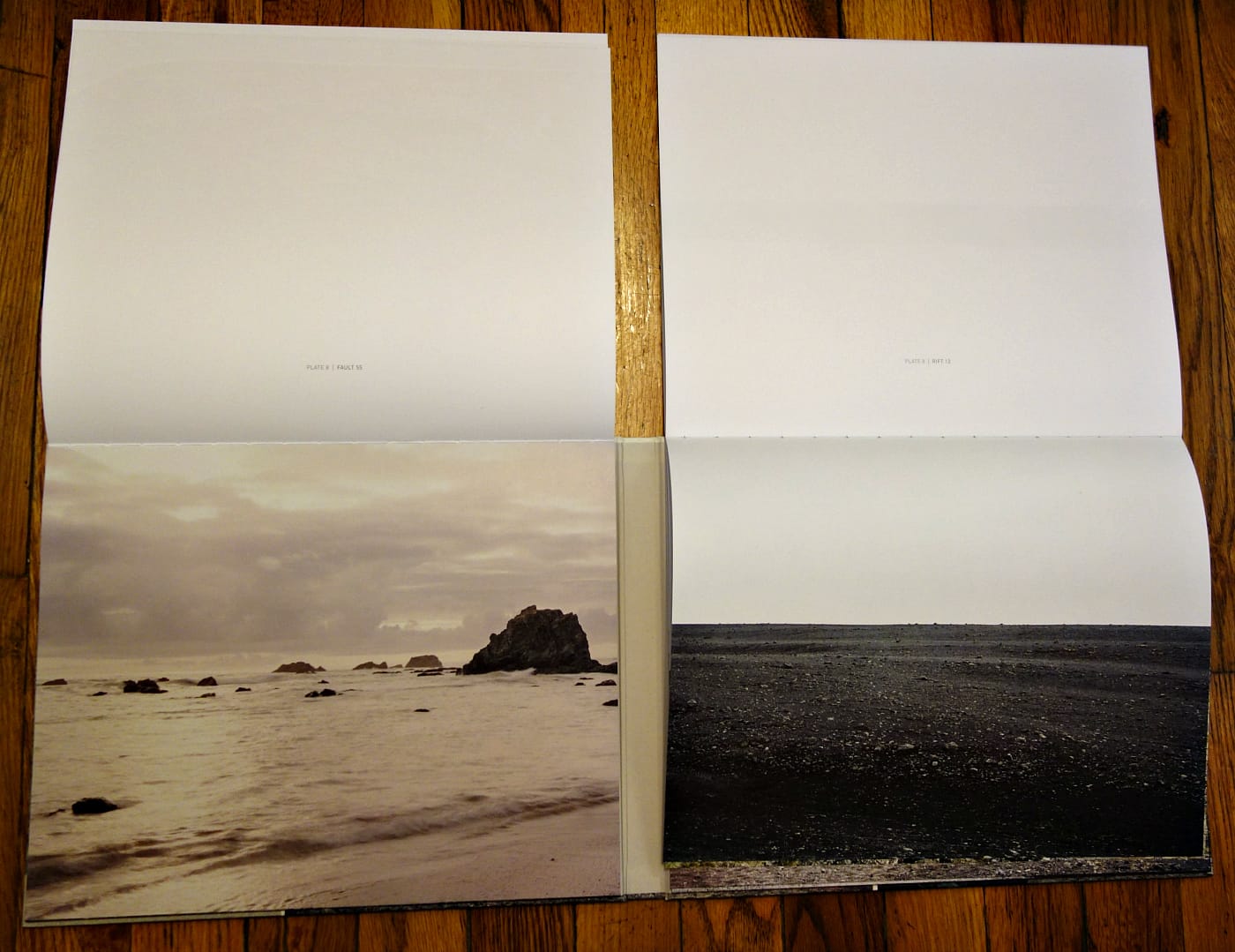

Rift/Fault, recently released by Radius Books, contrasts 48 of Belanger’s photographs from those two precarious locales. A cracked concrete retaining wall in Hollister, California, where the Calaveras Fault is splitting the city in two, is juxtaposed with a burbling mud pool in the geothermal area of Hverir, Iceland. Other images offer panoramas of the seismic scenery, such as the landslide-prone cliff of Daly City, which is perched above the San Andreas, and a dark volcanic excavation site alongside small houses in Heimaey, which experienced an eruption on January 23, 1973 — without warning, volcanic ash swallowed 400 of the island’s homes, creating a modern-day Pompeii. In another spread, Belanger compares a consumed Heimaey house with an empty one in San Bernardino, where the economic crisis stalled development.

Fog and mist, captured in cool light, visually connect these distant edges of the North American Plate, although Rift/Fault feels more like two books in its design. The California and Iceland photographs are sewn separately on either side of the hardcover monograph, so you can flip through them independently or as one. This makes it a little difficult to navigate the book except on a large table, and the captions and essay by art critic Lucy Lippard are presented in a separate pamphlet. Nevertheless, the book’s instability, with a physical chasm between its two subjects, reinforces the themes of Rift/Fault. It’s a photographic tour of places where humans continue to build, whether subdivisions or geothermal plants, even as recent histories of tsunamis and lava flows are visible. As Lippard writes in her essay:

Iceland, with its geothermal energy, hydroelectric, and wind farms (less than 0.1% of its power comes from fossil fuels) is a model for the rest of the world, especially as California burns. But it’s a trade-off. Unlike climate change and so many other vital ecological issues, there is nothing we can do about the great beast stirring restlessly beneath our feet, beneath our lives. It is what it is.

She adds, though, that this “powerlessness can remind us of what we can change.” Through mundane details of cactus farms and grand vistas of rocky boundaries, Belanger’s photographs add to our visual understanding of the colossal shifting of plates below the Earth’s surface.

Marion Belanger: Rift/Fault is out now from Radius Books.