Scrimshaw: A Lost Art of Boredom

19th century whalers could be at sea for years, and for those months surrounded by the perilous currents of the oceans, boredom was often the biggest danger. One of the art forms that emerged from this sanity-threatening tedium was scrimshaw, a time-enveloping practice of tattooing art onto bones.

19th century whalers could be at sea for years, and for those months surrounded by the perilous currents of the oceans, boredom was often the biggest danger. One of the art forms that emerged from this sanity-threatening tedium was scrimshaw, a time-enveloping practice of tattooing art onto bones.

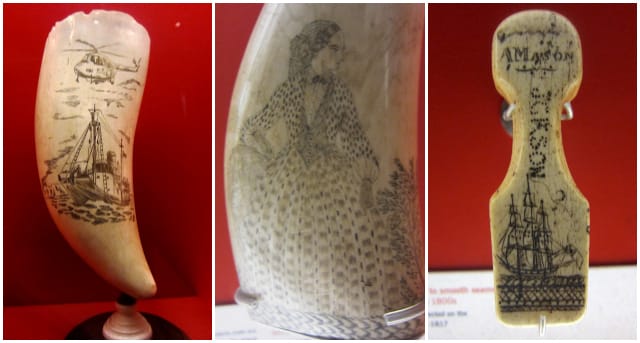

As our time whaling at sea has diminished, so has scrimshaw, but you can see a few incredible examples at the American Museum of Natural History in their current exhibition Whales: Giants of the Deep. Coming from both the museum’s permanent collections and the traveling exhibition, the scrimshaw reveals what was on the mind of these sailors isolated out in far flung corners of our watery planet.

“Whale-bone, I am told, lends itself as a medium easily to this type of marking with metal tools,” Peter Whiteley, Curator of North American Ethnology, explained. “Clearly excess whalebone and whale teeth was plentifully available to whalers—perhaps like wood if you live in a forest.”

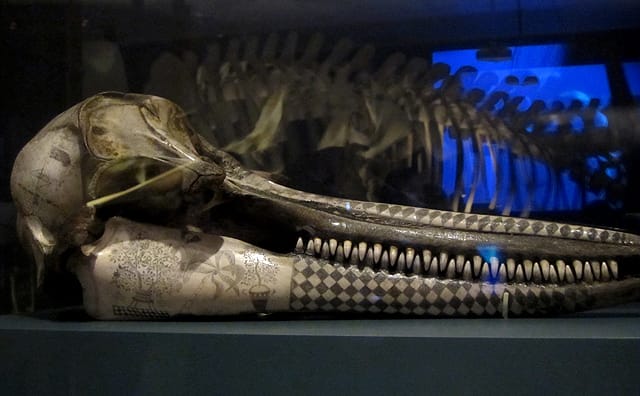

Most of the examples are on teeth, as these were readily available by-products of whaling on the ship, and you could obsess over a portable gift for your loved ones upon your return. Yet the highlight by far is a dolphin skull totally covered in designs that seem to have been picked up from a trip around the world, with exotic flowering trees on the lower jaw and painstakingly detailed ships and flags around the cranium, while the beak is checkered in black ink on either side. Months and months must have spent on it, although the exhibition remains vague, just giving the years as somewhere between 1750 and 1850.

Whiteley noted that sailors weren’t the only bored wanderers of the 18th century to create these carved designs, and that soldiers in the long French and Indian War (1754-63) also “carved scrimshaw-type designs, often with maps and other important historical information, onto powder horns.”

These “scrimshanders,” as scrimshaw practitioners are called, haven’t entirely disappeared. One interesting item in the exhibition is a sperm whale tooth decorated in scrimshaw by a Soviet Russian sailor in 1958, where the modern, arguably more brutal, whaling practices are shown, with a helicopter flying in advance to spot whales while a sailor stands ready with the harpoon gun on the deck. Whatever whale this came from obviously didn’t have a chance.

It’s kind of surprising with the surge of arcane salon style learning in New York, with classes on bone articulation, bitters making, millinery, and other 19th century-inspired skills, that no one has taken up the old tedious work of scrimshaw. That’s not to say it has died out completely, and there’s even a Scrimshaw Weekend coming up for its practitioners this month at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, but most of us just don’t have the time to sit around carefully carving an elaborate illustration into a whale’s tooth. Perhaps these examples at the natural history museum will inspire some artists to think of these lost arts of boredom and spend some time this summer seeing what kind of creativity can come out of having absolutely nothing else to do.

Whales: Giants of the Deep is at the American Museum of Natural History (Central Park West at 79th Street, Upper West Side) through January 5, 2014.