Opening Up the Museum to an Emerging Artist

The first view of Shura Chernozatonskaya’s work is on the soaring white wall of the Brooklyn Museum’s lobby, spanning over forty feet and high above viewer’s heads.

The first view of Shura Chernozatonskaya’s work is on the soaring white wall of the Brooklyn Museum’s lobby, spanning over forty feet and high above viewer’s heads. “Domino” (2012) is a painting installation of thirty-three canvasses set-out in a recognizable game formation: a yellow-to-blue chain tic-tacking its way across the threshold to the galleries. Each canvas is marked with approximations of the traffic-light symbol with circles of red/amber/green applied, in glowing transparency, to grounds ranging from pale lemon to deep indigo. Graphically cheerful in tone, the work nonetheless sparks significant cognitive tension. The integration of two distinct pictorially communicative systems, “domino” and “traffic light,” here orchestrates a string of yes/no, stop/go associations in a reception space where viewers’ expectations are strongest. “Domino” is a youthful work. It suggests a brave execution — an exuberant, if harmoniously imperfect, immersion in color and play — and is a fitting symbol to Raw/Cooked, the Museum’s bold new exhibition series of emerging artists of which Chernozatonskaya is the featured third.

Raw/Cooked is curated by Eugenie Tsai in collaboration with an advisory board of established Brooklyn artists. The aim of the series is to feature underexposed artists through the direct incorporation of their works into the museum’s permanent galleries. It is, in essence, an uncontrolled curatorial experiment within one of the city’s most important museums, and the value of the endeavor is significant. It takes an almost reckless courage to open up establishment doors to an emerging artist, and allow them to make the museum his or her own. In this case the payoff proves proportionate to the risk. Raw/Cooked bluntly posits the importance of an emerging artist within a context of visible tradition, and in so doing addresses central issues of contemporary artistic practice: what is the relation, if any, of artwork being made today to that of the canonized past? What is the museum’s role in dissemination of contemporary artwork? The answers are ventured materially, rather than theoretically, through this current exhibition, and its strength owes much to the thoughtful and self-conscious way in which the artist has matched her works to the challenge of the scenario.

Born in Moscow and now based in Red Hook, Chernozatonskaya studied classical piano at Oberlin before earning her master’s degree from New York’s Hans Hofmann-esque Studio School in 2006. Related, perhaps, to these earlier studies is the attitude towards tradition on view in this exhibition which is at once reverent and playful. Having selected some of the Museum’s most architecturally impressive environments in which to show, she created large-scale paintings reflexively in response to the spaces and pieces in the collection. The result is an ambitious body of work, which nonetheless appears to have been shaped at its inception by an attitude of curiosity, one even senses humility, towards the possibilities latent in the Museum’s august surroundings.

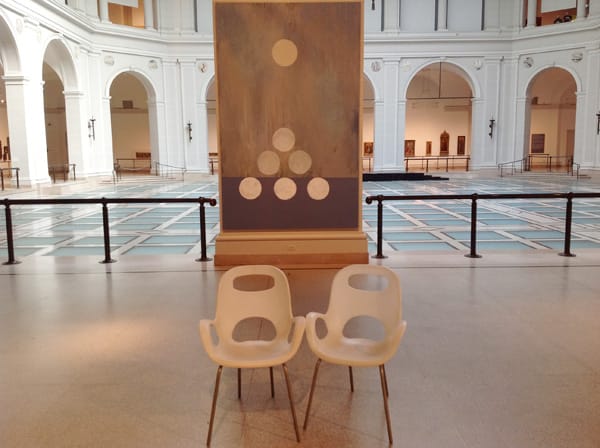

The second and main part of exhibition takes place in the museum’s enormous skylit European-gallery courtyard. Chernozatonskaya’s works here display greater range, subtlety and surprise than in the lobby’s introductory piece. The installation consists of eight paintings, two for each side of the courtyard’s square arcade gallery, where the museum has grouped key works from the collection into four themes: Tracing the Figure; Art and Devotion; Land and Sea and Russian Modern. Chernozatonskaya’s works are hung on the column-like walls demarcating the inner courtyard, opposite paintings by masters such as Goya, Picasso, Soutine, Bellini, Monet and Kandinsky. Although Chernozatonskaya’s panels each measure a sizeable 6’ x 8’, their placement within the gallery sets them apart from the permanent works by allowing them to exist in quiet parallel. The serendipitous hanging supports what appears to be the artist’s intentions, which is to use the museum’s thematic scheme through the quiet echoes of influence.

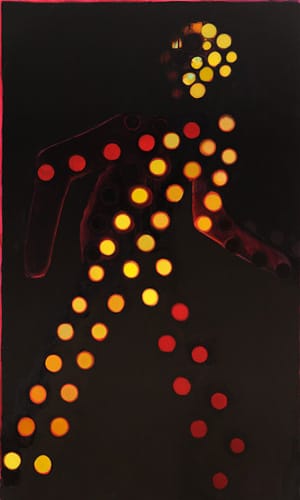

“Tracing the Figure: Man” (2012) is among the strongest of the works. Placed opposite portraits by Picasso and Goya, this painting picks up from where the Spanish red-to-black color sensibility leaves off. It depicts, six feet high, the iconic signage symbol of “man.” In this contemporary portrait “he” is slipping into tonal and existential obscurity, as the crimson pixels-shapes which define him sink into an expansive ground of subtly modulated darkness. The tableaux is re-activated by a slight frame of reddest-red underpainting left visible towards the top — a reminder that this “man” is, prior to his sign/symbol existence, a pure creature of color and imagination.

A similar tense dynamic between symbol-shape and color plays out through the diverse works which complete the show. The circle-forms so prominent in the lobby piece are put to work in a range of scenarios: cue-balls (or snowballs perhaps?) gather mysteriously in battle formation within the white-to-grey abstractions of the Russia Modern section. They appear later, movingly, as haloed faces in the Art and Devotion quarter of the show: shy icons peering out towards the viewer from void-like shrouds of gold and green. For all of the sophisticated play between source and imagery, not to mention the formal agility required in response to four distinct themes, Chernozatonskaya’s paintings are ultimately grounded in a Color Field sensibility. The evocative strength of her statements lies in the broad areas of color that make up her works, and in an application which suggests total commitment to the visual force inherent to pure, unmodulated hue.

It is unlikely that anyone would mistake Chernozatonskaya’s work for anything other than that of a younger artist. Moments of tentativeness can sometimes suggest her paintings as having a prototype, rather than a product existence. It would be difficult to deny, however, that this exhibition successfully features the very best traits of an emerging artist’s work: vitality, bravery and a full engagement with the possibilities of the medium. Implicit to Raw/Cooked is a question not always meaningfully addressed in the current critical system, namely when is an artist really ready to show? In contrast to the dominant thesis project-driven model for aspiring artists, Raw/Cooked suggests a more organic scenario. It is as though the artists featured here, though a process akin to blooming or ripening, simply become ready at some internally-determined point to join the conversation surrounding important works of art.

Shura Chernozatonskaya’s Raw/Cooked exhibition continues at the Brooklyn Museum ( (200 Eastern Parkway, Prospect Park, Brooklyn) until April 8.