Still Chill

Remember when chillwave was considered a genre? Remember when a select number of elite, unrelated, alternative-identified musicians making slow, synthy loungetronica were considered the future of Western civilization?

Remember when chillwave was considered a genre? Remember when a select number of elite, unrelated, alternative-identified musicians making slow, synthy loungetronica were considered the future of Western civilization? Back before indie obsessives realized that these musicians — rather than cutting conventional electropop with distortion and reverb effects in an acceptably ironic rejection-embrace — were just earnest artisans crafting feelgood, escapist ear candy? The vaguely chillwave-associated Ariel Pink remains active, and Animal Collective frontman Noah Lennox, who preceded these succès d’estime chronologically but fits right in sonically, returned this year with a fairly consistent solo album. But Neon Indian hasn’t released a new full-length in four years; Youth Lagoon, for all his hype, failed to catch on; and Washed Out, whose follow-up two years ago proved all but indistinguishable from his debut, earned for his efforts unmitigated critical indifference. My, how quickly fashion recycles itself; how quickly dilettantes playing with themselves slip passively through the drain, carried along by the bathwater. Only Toro y Moi, plodding on faithfully, continues to make the music that so ignited the blogosphere in 2010.

Now generally recognized as a classic example of eager bloggers announcing the existence of a so-called trend way too early and on way too little evidence, chillwave nevertheless does command its own rough aesthetic: hazy electronic rock, with mild vocals and awkwardly cheerful melodies. A natural corollary of the homegrown psychedelia pioneered/patched together/accidentally stumbled upon by Animal Collective, chillwave’s distinguishing factor was an extra coating of cloudy synthesizer vapor that obscured lyrical details, downplayed rhythm, and pursued ambience, further diminishing the tangible songform in the Animal Collective style while stressing all the glittering sound effects. Essentially, this is a modern version of what bands like the Zombies, say, were doing in the late ‘60s, using electronic sequencing technology to replicate kaleidoscopic, drugged-out studio techniques that used to require the physical playing of instruments. But because the vocals have gotten so much breathier, the tempos so much slower, and the textures so much more monolithic, its overall impact reminds me of digitally adjusted shoegaze flattening the listener with an impressionistic wash of soft, sensual sound, inserting computerized guitar replications where actual distorted guitars used to be. Between those two far-fetched comparisons lies Toro y Moi. Since Toro y Moi’s music includes audible drums and outgoing tunes, his records assert themselves with more confidence than those of the totally misty and opaque Washed Out, and perhaps this explains why he’s lasted longer than his contemporaries. His new album, What For?, features ten scrupulously polished tracks, each instantly recognizable as a clear, comprehensible song. Whether or not the lyrics actually make sense matters considerably less than the fact that they can be deciphered at all.

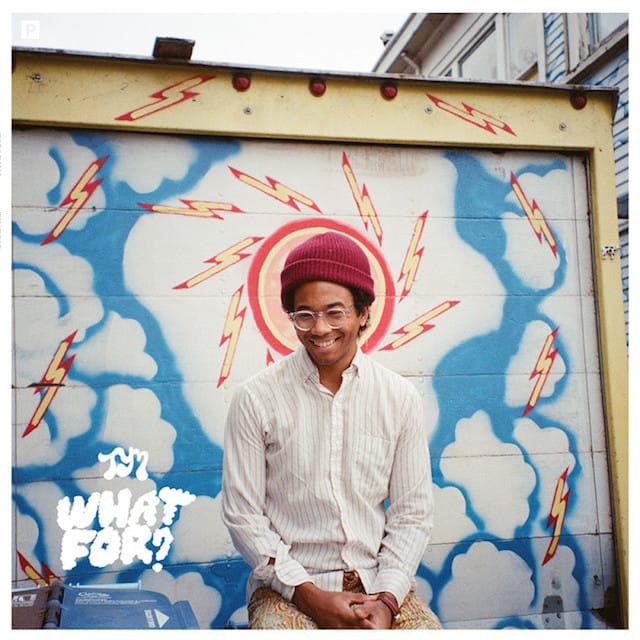

Toro y Moi is Berkeley electroauteur Chaz Bundick. Although he tours and records with a live band, his absurd pseudonym refers to himself only. He has also recorded under the names Les Sins and Sides of Chaz. What For? is his fourth album as Toro y Moi; while the others fill out a constantly kooky, rubbery palette, 2011’s Underneath the Pine is, very roughly speaking, the most engaging, and 2010’s Causers of This the most difficult. Causers of This revolved around samples and unfolding textures, while Underneath the Pine sacrificed samples for a working band that stayed with him on 2013’s Anything in Return and What For?. He specializes in smooth, midtempo quirkpop somewhat livelier and a tiny bit more tuneful than any of the aforementioned chillwave artists, with committed rhythm guitar and subtle background harmony keeping the music’s floaty qualities under control. Rather than inventing sounds and patterns and minimalist mantras to build on, you get the sense he sits down and writes coherent lyrics, devises a corresponding verse-chorus-verse structure, and then adds the sonics. That is, he performs songs, not compositions — his music is arranged melodically enough and sung articulately enough that he successfully creates the illusion of expressing himself. Additionally, from shimmering ostinato to whistling siren to goofy clavinet to low sliding bass to high dinky piano to hyperactive acoustic strumming to an endless flood of wah-wah keyboard to his intermittent faux-Brit vocal filter, his sonics are distinctive and diverse where his contemporaries settle for somber and monochromatic. His albums have a tangible feel. They’re amusing to listen to.

What For? certainly goes overboard on the sound sensation, keying every song to a specific instrumental jolt or buzz or wriggle. “Buffalo,” one of the faster numbers, sticks in the mind’s ear by way of jerky staccato chords, while “Spell It Out” joins an electric funk figure with a pretty bassline to a sudden burst of falsetto on Bundick’s part to intoxicating effect. The thin clouds of atmosphere behind “Run Baby Run” actually lend an appealingly smoky feel to the sunny chorus, and elsewhere the circular keyboard whirlicopter spinning its way into so many of these songs provides musical continuity on a record whose inventive, almost unstable sonic range could very well make for a disjointed listen. The melodies have a way of proceeding happily as usual until tripping over some weird chord change or unconventional harmony before just barely recovering and flowing away. His singing, friendly but rather ordinary, rarely makes these melodic devices sound anything but gauche and self-conscious, especially when he overdubs himself with sappy squealing about two octaves up from his normal range (except on “Buffalo,” whose sheer rhythmic eccentricity makes your ears twitch despite it all). Bundick seems sincerely to believe that he’s making straightforward pop music, and he’s right in a way. It’s all so pleasant and unobtrusive, so well-groomed, so mild. Whatever blatant flaws in craft, the ultimate package is disconcertingly streamlined, easily and instantly digestible, totally ready for passive consumption. Not even the extensive reverb pedaling that is chillwave’s hallmark adds the slightest bit of fuss — for other edgier artists, keyboard haze functions as a wall to hide the music behind; for Bundick, his various adventures in the land of the synthesizer serve up a sleek, tasteful, adult cosmopolitanism, attenuating his textures down so finely that only a seasoned connoisseur’s mind could know them all. Dependent on global tonal range to differentiate each song, adrift in an ocean of beatitude and blanditude, this is comfort food for bored aesthetes, chicken soup for the pseudointellectual soul.

My fantasy of an ideal Toro y Moi album cuts the reverb entirely and strips the lineup down to a single keyboard, a guitar or two, and drums. Thus would spareness magnify the need to write intelligible songs, and Bundick would rise to the challenge, penning a unified set of consistently strong, happy tunes. He might venture in this direction anyway; What For? is already a lot more pop-friendly than its predecessor, Anything in Return. It might also not make a difference. Sometimes the problem with an artist has nothing to do with message, or content, or cultural context, or what the artist stands for. Sometimes the problem with an artist is purely formal. The artist simply lacks the acuity to produce art that other people find compelling. Nothing clicks; everything fizzles; the artist stands revealed as a dilettante.

What For? and Anything in Return are available from Amazon and other online retailers.