When an Art Fair Becomes a Place for Discovery and Unexpected Pairings

It's in the quaint, quirky artworks that TEFAF becomes much more than a bazaar for the decorative.

Typically, when I’ve visited TEFAF (short for the European Fine Art Fair) in the past, I’ve been most attentive to the paintings, but this time, objects that had been on my periphery came into clear view.

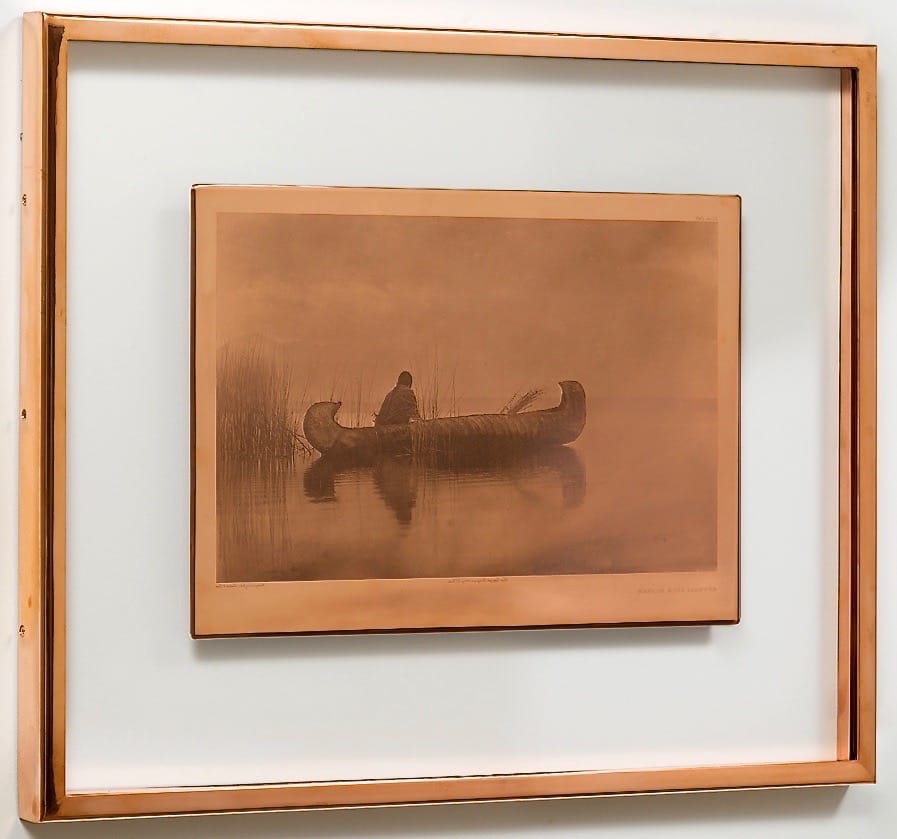

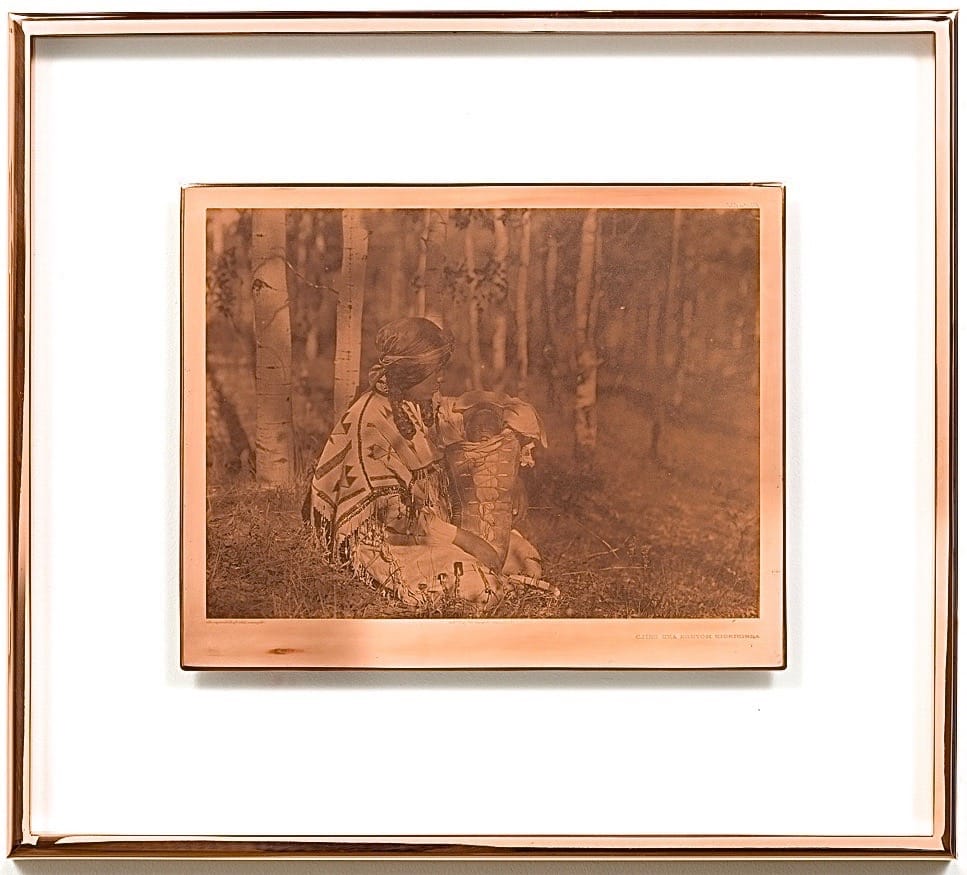

The first set of objects that mesmerized me were the copper photogravure printing plates of Edward S. Curtis presented by the Bruce Kapson Gallery. I understand that Curtis is a contested figure. He was an ethnographic photographer whose massively comprehensive project, The North American Indian, documented about 82 Indigenous American tribes in images that established for outsiders blinkered and stereotypical understandings of Native Americans. But I had never seen the plates up close. They are set within pristinely clear acrylic fields that mimic fine art photo matting with an outer frame of gleaming copper that mirrors the plates. The figures in the plates seem etched with graphite, dark against the sanguine backdrop in extravagant detail. Hair pulled into winged buns, birch bark, and still water all seem carved out of the world with a devious knife. I would rather look at the plates than the photo images made from them just about any day.

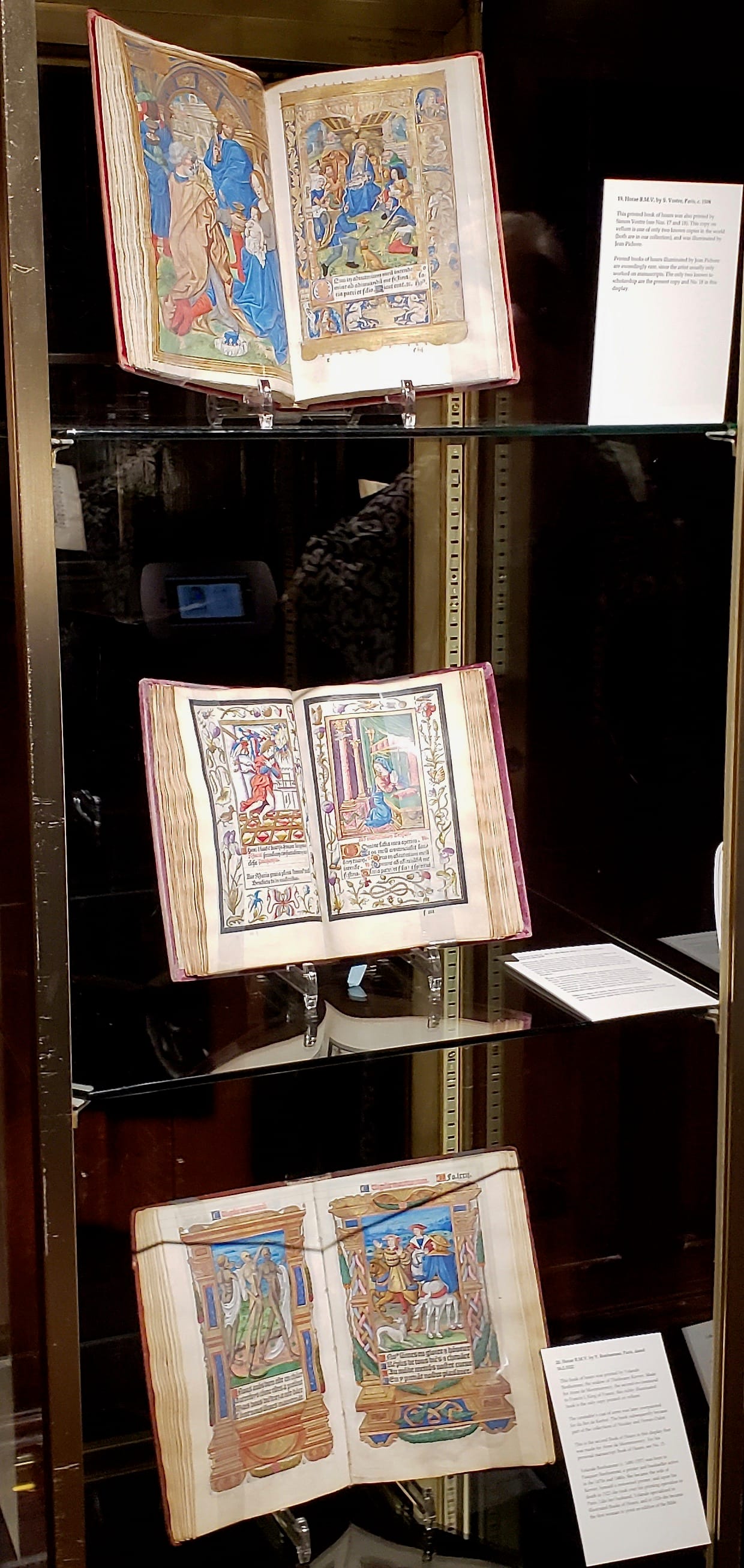

Other objects that I have glimpsed elsewhere but never paid attention to included the illuminated manuscripts in the booth of Heribert Tenschert, a Swiss collector of antiquities. The history of the particular books they had on display is fascinating: one designed by Geoffroy Tory introduced a type design that did not mimic handwriting and purportedly initiated the art of book design in France. It is also one of only three existing books that are known to have been printed on vellum. The associate of the gallery confirmed that the pages consist of Latin and explained that the particular tome is a book of hours, a religious guide that contained prayers and psalms a follower would refer to throughout the day. At another gallery, Mireille Mosler, I saw a lovely portrait of two nuns, and the older one holds what might well be a book of hours.

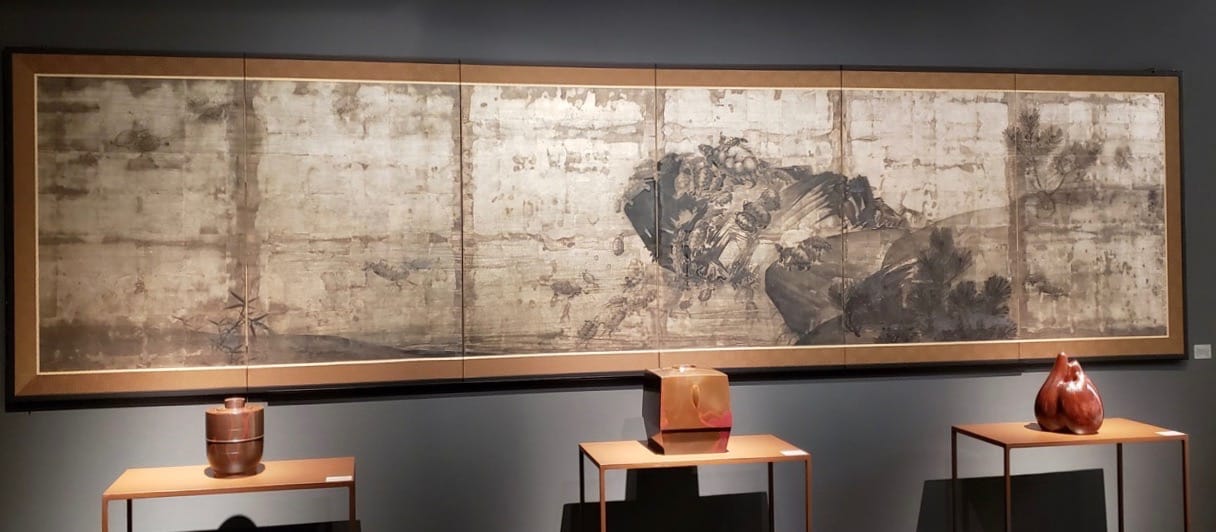

Another non-painting highlight was an El Anatsui draped tapestry, presented close to an ancient Egyptian head of a pharaoh (ca. 589–570 BCE), at the Axel Vervoordt gallery. This display scheme strikes me as a strange homology since El Anatsui is Ghanaian working primarily in Nigeria, and in the 21st century, no less, while the Egyptian artifact is both geographically and chronologically distal. Another gallery, Colnaghi, featured a long display table of Central and South American mace heads, which displayed this manner — on a table without any contextualizing information as they would be at a bazaar — suggested that they might be purchased as tchotchkes for someone’s home office, a paper weight with an intriguing back story.

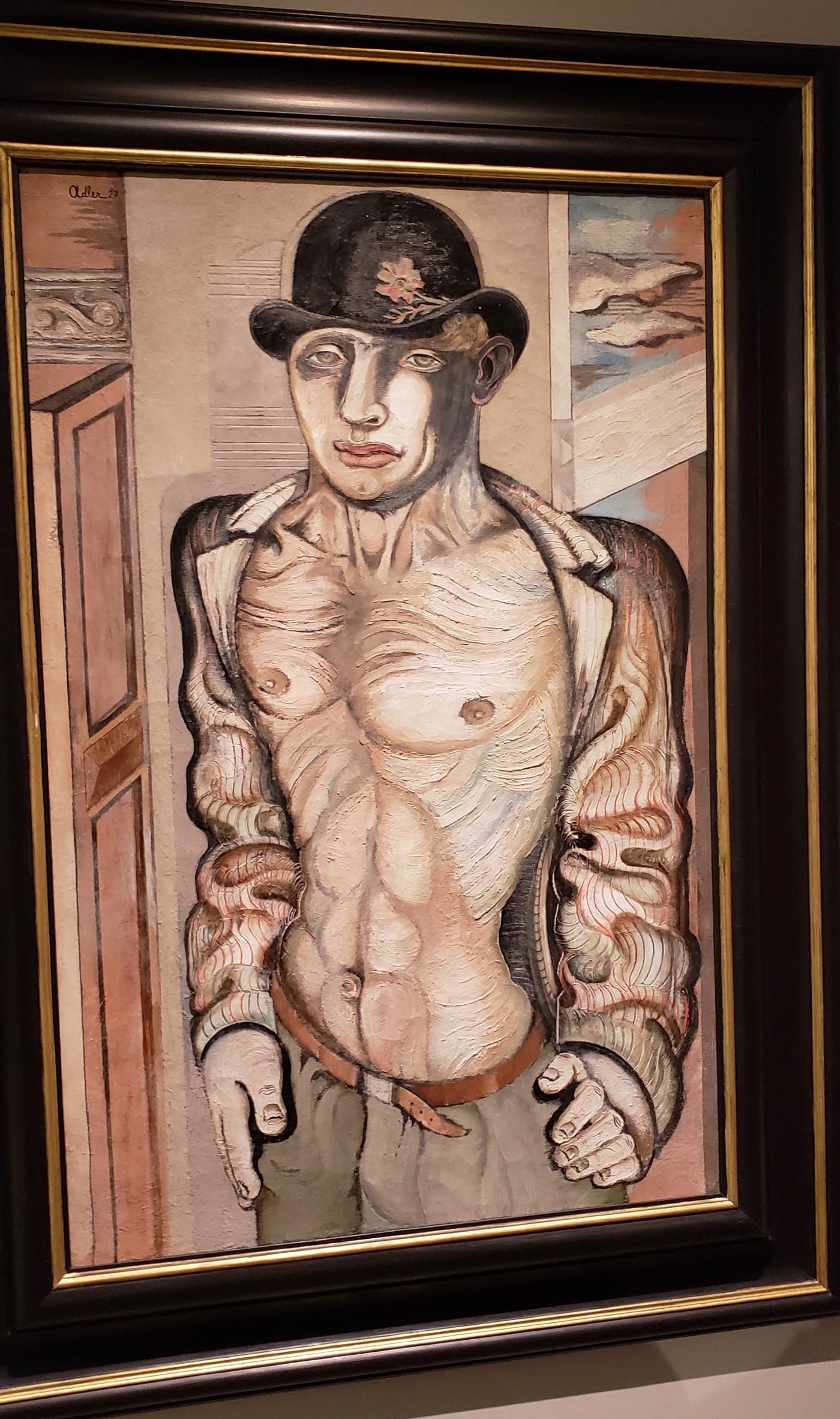

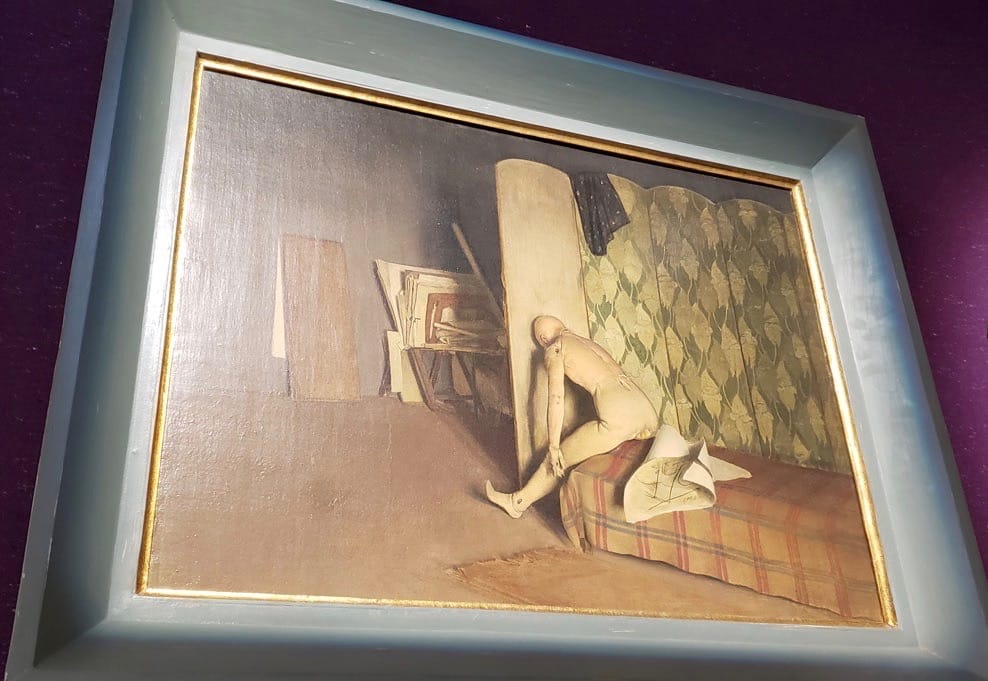

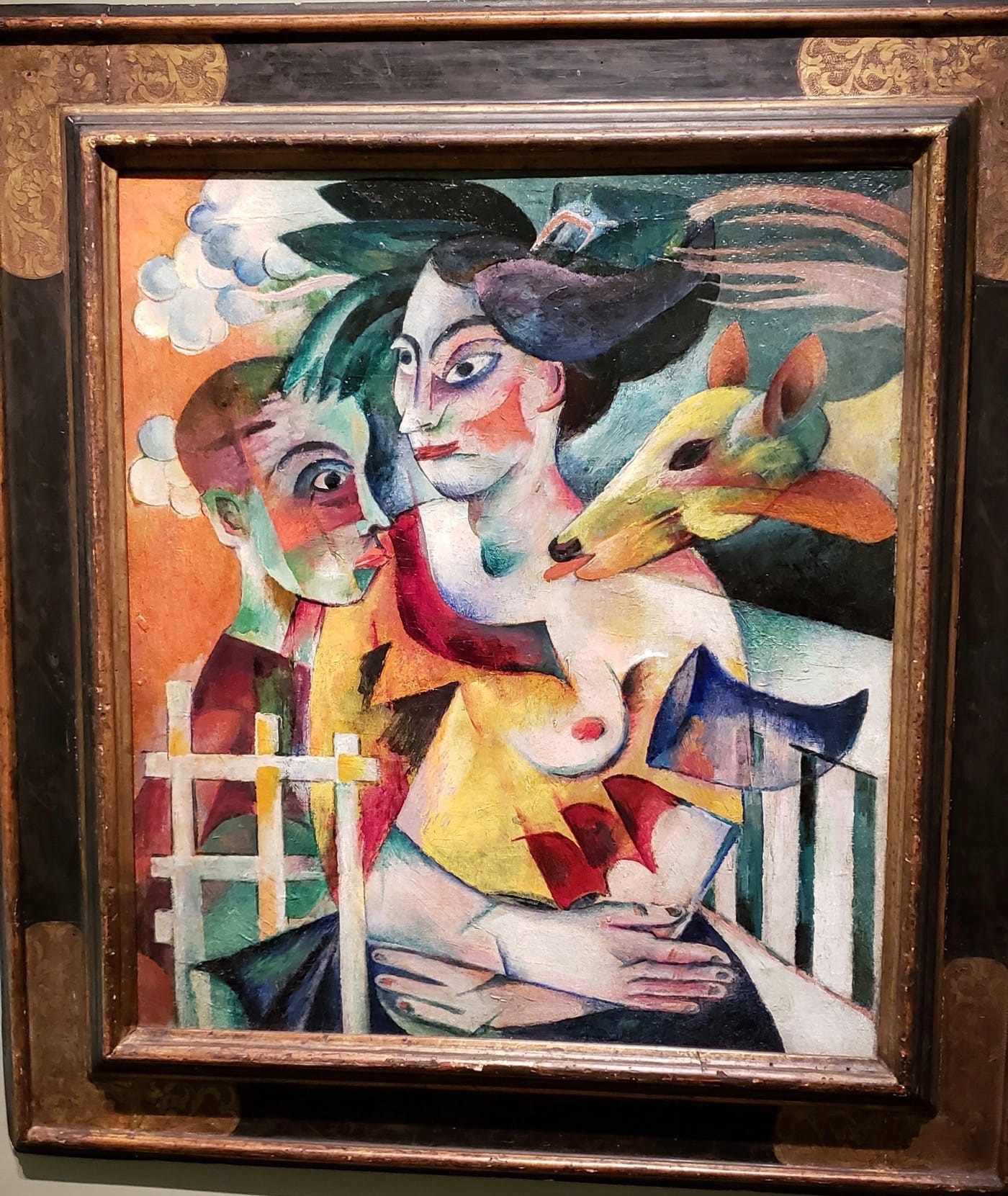

TEFAF, which proclaims itself to be a fair of fine and decorative art from antiquity to 1920, offers a manageable and even fun experience for me, because I just ignore all the jewelry and ornamental schtick and look for the unexpected art. Inevitably, I did find some paintings that were quirky and surprising like the Pietro Annigoni portrait of what looks like an inert man on the edge of a couch, with his head collapsed against a dressing screen. The title gives the game away though: “A Mannequin in a Studio” (1947). Lastly, there is the Heinrich Campendonk portrait “Mother with Child and Deer” (ca. 1913) which looks like a lavish fusion of Surrealism, Cubism, squeezed through the palette of Franz Marc of the Blue Rider Group. It’s in those pieces when the TEFAF becomes much more than a bazaar for the decorative: It becomes a place of discovery.

TEFAF continues at the Park Avenue Armory (643 Park Ave, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through October 31.