The Anti-Spectacle of the Black Avant-Garde

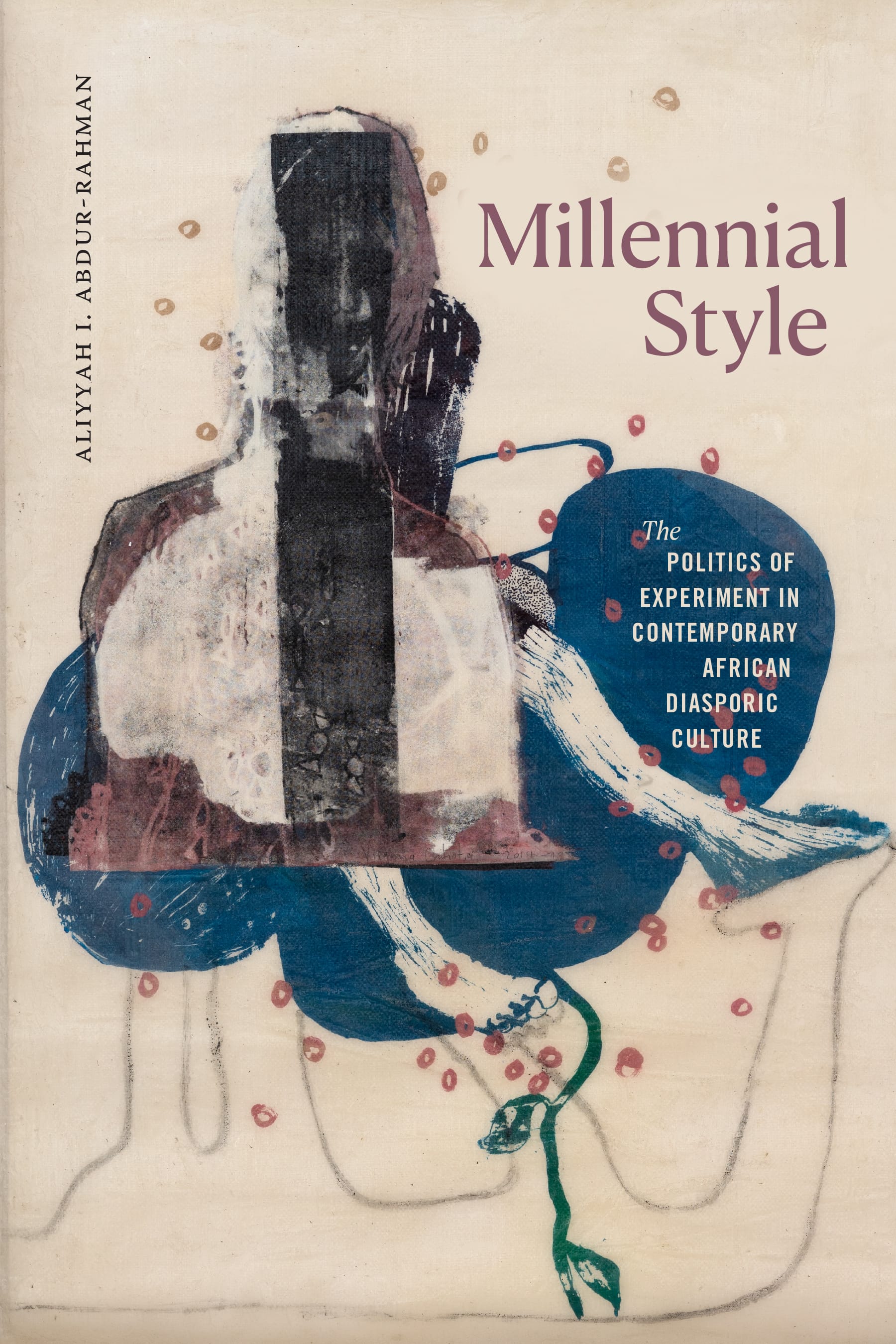

Aliyyah Abdur-Rahman’s Millennial Style considers the political utility of Black abstraction and related forms to refute false narratives of progress.

A tremendous offering to Black studies and cultural criticism has just entered the conversation. Aliyyah Abdur-Rahman’s Millennial Style: The Politics of Experiment in Contemporary African Diasporic Culture (2024) examines the political urgency of formal experimentation in recent Black visual, sonic, and literary culture. Addressing our present moment and the histories that bear on it, Abdur-Rahman analyzes the anti-representational strategies of contemporary Black cultural production. In the introduction, she delineates the contours of a 21st-century Black avant-garde that chose abstraction and other non-realist methods to escape the constraints of normative representation, and the creative offspring of their experimentation. The core chapters of the book are organized into four critical concepts: “Black Grotesquerie,” “Hollowed Blackness,” “Black Cacophony,” and “The Black Ecstatic.” Each chapter contains profound implications for how we interpret the politics and aesthetics of post-civil rights Black cultural production.

Abdur-Rahman grounds her argument in the realities of Black life, from which avant-gardist practices with radical possibilities emerge. In the dominant teachings of neoliberal democracy, we are taught that seeking representation in the institutions that kill us will bring incremental change and, eventually, comprehensive equality. Contrary to that narrative of inevitable progress, the recursive nature of anti-Blackness reveals a difficult truth: “Never in modernity — this period that founded new empires and global economies through the transatlantic shipment, sale, and forced labor of millions and millions of Africans — have we secured or even approached durable black freedom.” Neither witnessing nor protesting, she points out, has “curtailed the sickening accumulation of black corpses.”

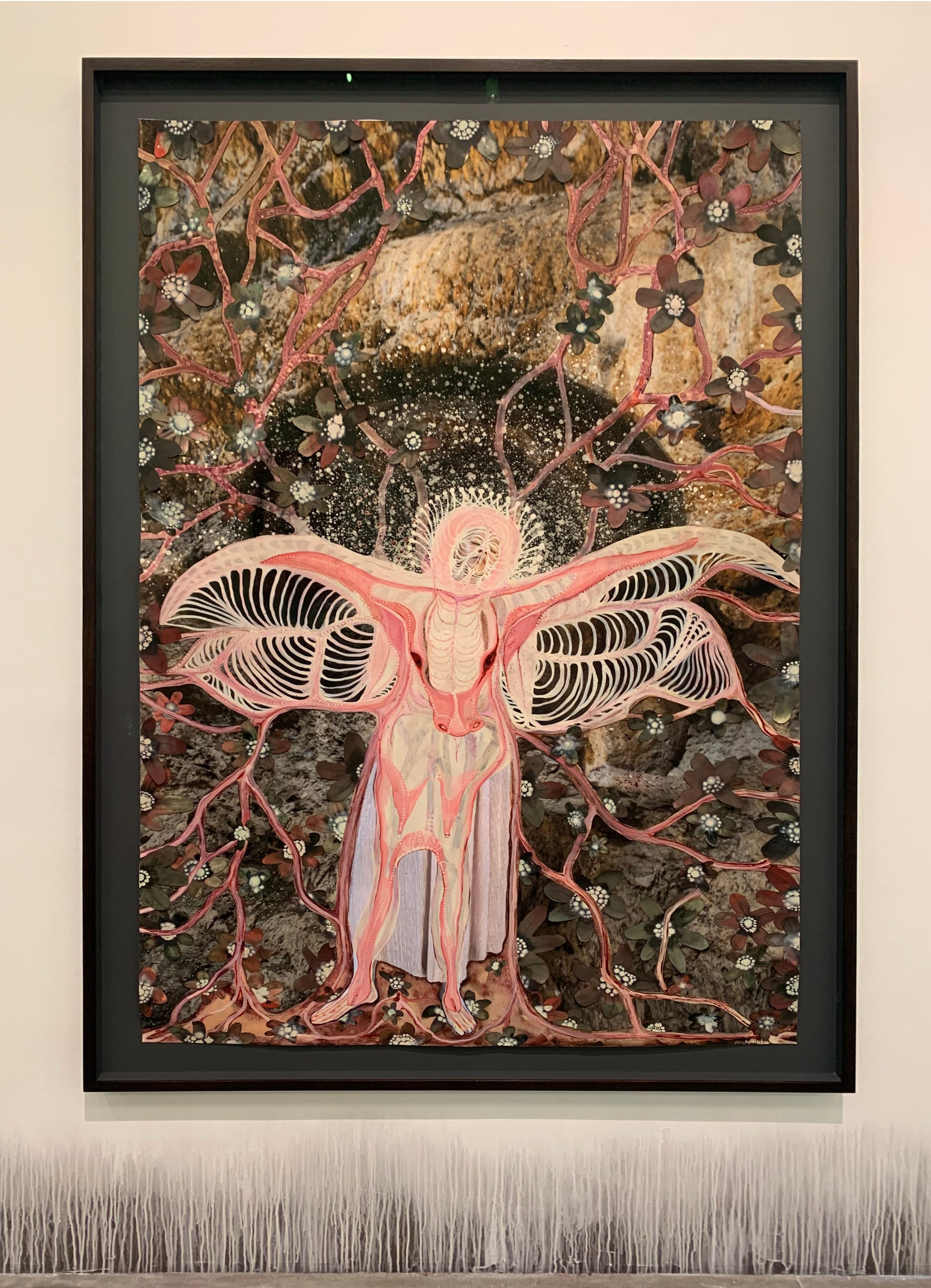

Abdur-Rahman builds the concept of “Black Grotesquerie” to describe aesthetic practices that capture racialized abjection, or radical possibility, through renderings of Black life at the porous borders of horror and freedom, living and dying, desire and disaster, and so on. I understand Black Grotesquerie as a mode through which artists confront the wreckage of a world built on anti-Blackness and choose to build an alternative. Indeed, it’s only through our refusal of a colorblind or postracial notion of existence that we live as Black people not (at least fully) fixed in what Abdur-Rahman aptly considers our “catastrophic present.” Wangechi Mutu’s mixed media collages and sculptures serve as the primary visual sources in this chapter. In “Howl” (2006), for instance, the anatomical disfiguration of Black women’s embodiment, in the literal sense of splattered blood and the metaphorical form of bleeding earth, creates an assemblage of forms both familiar and confounding. Mutu’s turn toward the grotesque to confront the anatomy of both Black people and Black worlds marked by slavery and colonialism exemplifies the regenerative capacities of experimental forms that don’t depend on building upon the anti-Black structures that exist.

In “Hollowed Blackness,” Abdur-Rahman urges us to reconsider Black space and freedom by contending with practices of enclosure that evade literal and representational capture, such as Harriet Jacobs’s fugitive confinement to her grandmother’s attic crawl space as detailed in her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861). Alexandria Smith’s mixed media representations of Black girls communing in hidden spaces illustrate Black feminist communality across “hideouts, watery enclaves, and fragmented terrain.” Rendered abstractly in mirrored poses and shadows, the hollows in Smith’s representations evoke Black feminist practices of concealment that protect, create privacy, and maintain togetherness.

The chapter “Black Cacophony” addresses sound; it is the “aesthetic of noise within language, at its limits.” Examples are “screaming, wailing, blabbering, moaning, howling.” These sounds embody the incommunicable horrors of racial slavery and its afterlives: “Speech recoils from that which evades human comprehension.” Abdur-Rahman analyzes Harmony Holiday’s digital project, “The Black Catatonic Scream” (2024), in which the Swahili word Maafa, meaning catastrophe, is repeated throughout. The enunciation of Maafa recognizes centuries of genocidal violence and enslavement that produces ongoing terror for African peoples throughout the world.

The “Black Ecstatic" is perhaps the concept most entangled with physical pleasure, although it leaves space for varied affective possibilities and sensations. Embodied touch, relation, and political desires imbue the difficulty and uncertainty of Back queer life with the joy and possibility of a world beyond the present one. Grappling with desire and disaster in Barry Jenkins’s film Moonlight (2016), Abdur-Rahman notes that the premature death and incarceration of characters take place off-screen, granting Black people a sense of intimate privacy we are regularly denied under the surveillance of an anti-Black society. Instead, there is “fleeting, rapturous communion between subjects gendered black and male.” Such entanglement between pain and pleasure is pertinent, “for it is in the intersection, the churning overlap, of catastrophe and ecstasy that we may encounter a perilous and queer black freedom.”

In taking special notice of the ubiquity of Blackness and Black art in contemporary cultural production, as well as politically charged rejections of realist representation, Millennial Style characterizes the Black avant-garde as an “aesthetic repudiation of spectacularity” in which the political pressure for normative representation is replaced by a desire for opacity that occludes dominant gazes. Abdur-Rahman’s critical intervention ought to mobilize critics of art and culture to consider the political utility of Black abstraction and related experimental forms while refusing narratives of progress that erase the immense suffering of a modern world created by a consistently shapeshifting anti-Blackness.

Millennial Style: The Politics of Experiment in Contemporary African Diasporic Culture (2024) by Aliyyah Abdur-Rahman is published by Duke University Press and available for purchase at online Bookshop.org and in bookstores.