The Art of Fallen Cities

BOSTON, MASS. — Having grown up on the Great Plains, the first ruin of the Romantic variety I remember encountering was the shell of the Rock of Cashel in Ireland.

BOSTON, MASS. — Having grown up on the Great Plains, the first ruin of the Romantic variety I remember encountering was the shell of the Rock of Cashel in Ireland. Sure, there are plenty of decrepit farmhouses, and some Mississippian mounds, haunting my home turf, but this roofless stronghold with its soaring window frames evoked a more melancholy, old world abandonment. If this was today, I would have posted an appropriately moody Instagram of its gaping cathedral. As I was 19, I wrote a poem instead that’s now lost to its own passage of time.

That impulse, however successful, to respond to the relics of the past with brooding on their meaning in regards to our mortal transience is an enduring theme of art. In the 1860s, Roger Fenton photographed two women resting beneath the arches Tintern Abbey. Its vacant stones have a medieval architecture similar to the Rock of Cashel, and encouraged many a poet from William Wordsworth to Thomas Gray to write a few lines about their decay and symbolic tranquility. Fenton’s image is among 40 works on paper on view in Ruined: When Cities Fall at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). The exhibition explores this fascination of fallen cities in art, from the Renaissance to the present.

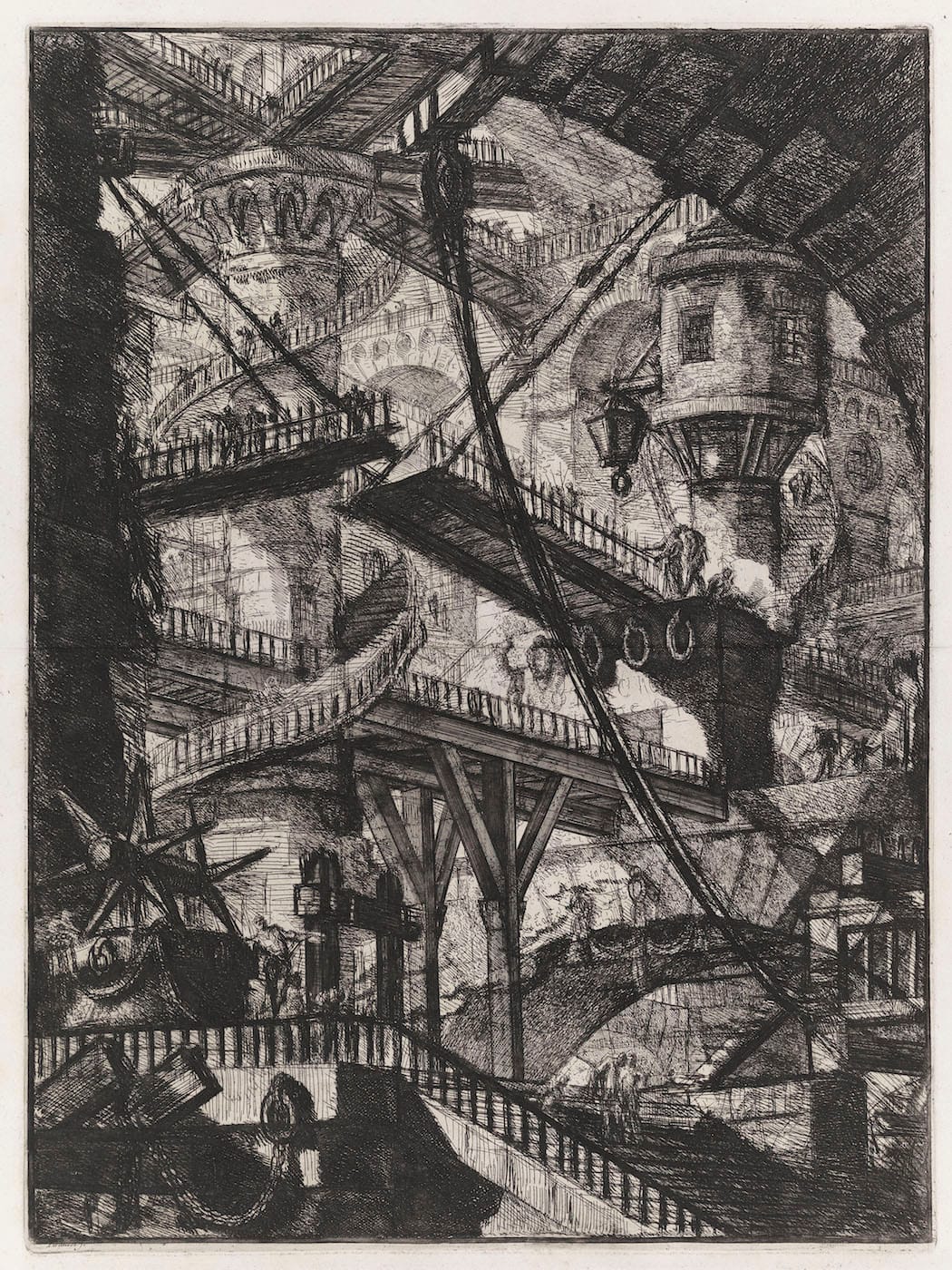

Ruined was organized in conjunction with Megacities Asia, an exploration of the meteoric growth of Beijing, Shanghai, Delhi, Mumbai, and Seoul, which closed in July. However, Ruined stands on its own in one long gallery as a sort of portrait hall of doom. Bartholomeus Breenbergh’s 1627 brown and gray wash painting portrays the Roman Colosseum as a shadowy specter of the past hovering over a small traveler with a dog, and four 16th-century etchings by Hieronymus Cock document more of Roman antiquity overgrown on the city’s outskirts, including a reminder of just who he considered to have destroyed the Colosseum (the “Barbarians”). Giovanni Battista Piranesi morphed his 18th-century studies of Roman ruins into fictional “prisons of the imagination,” which responded to the shattered structures with elaborate, foreboding constructions.

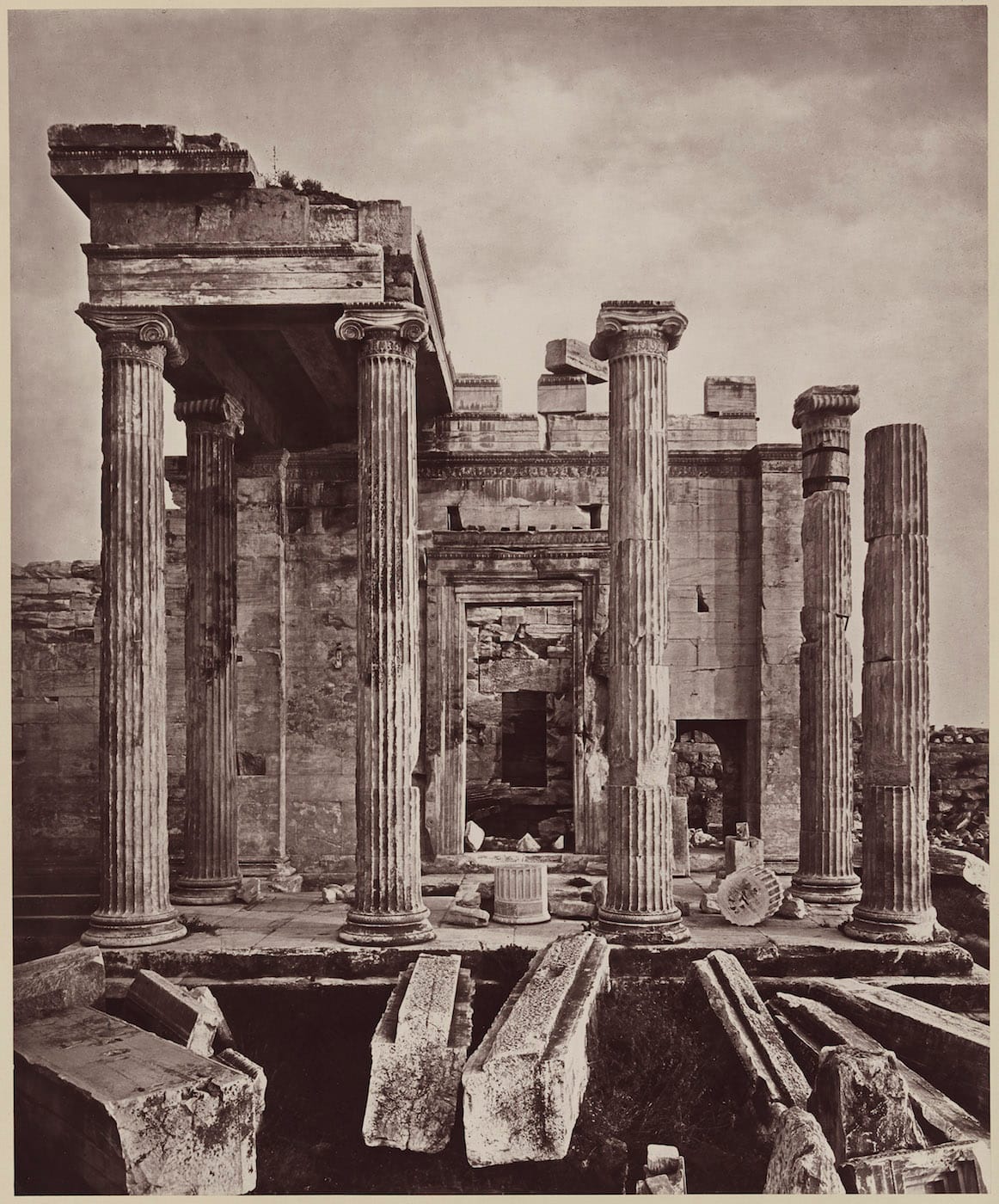

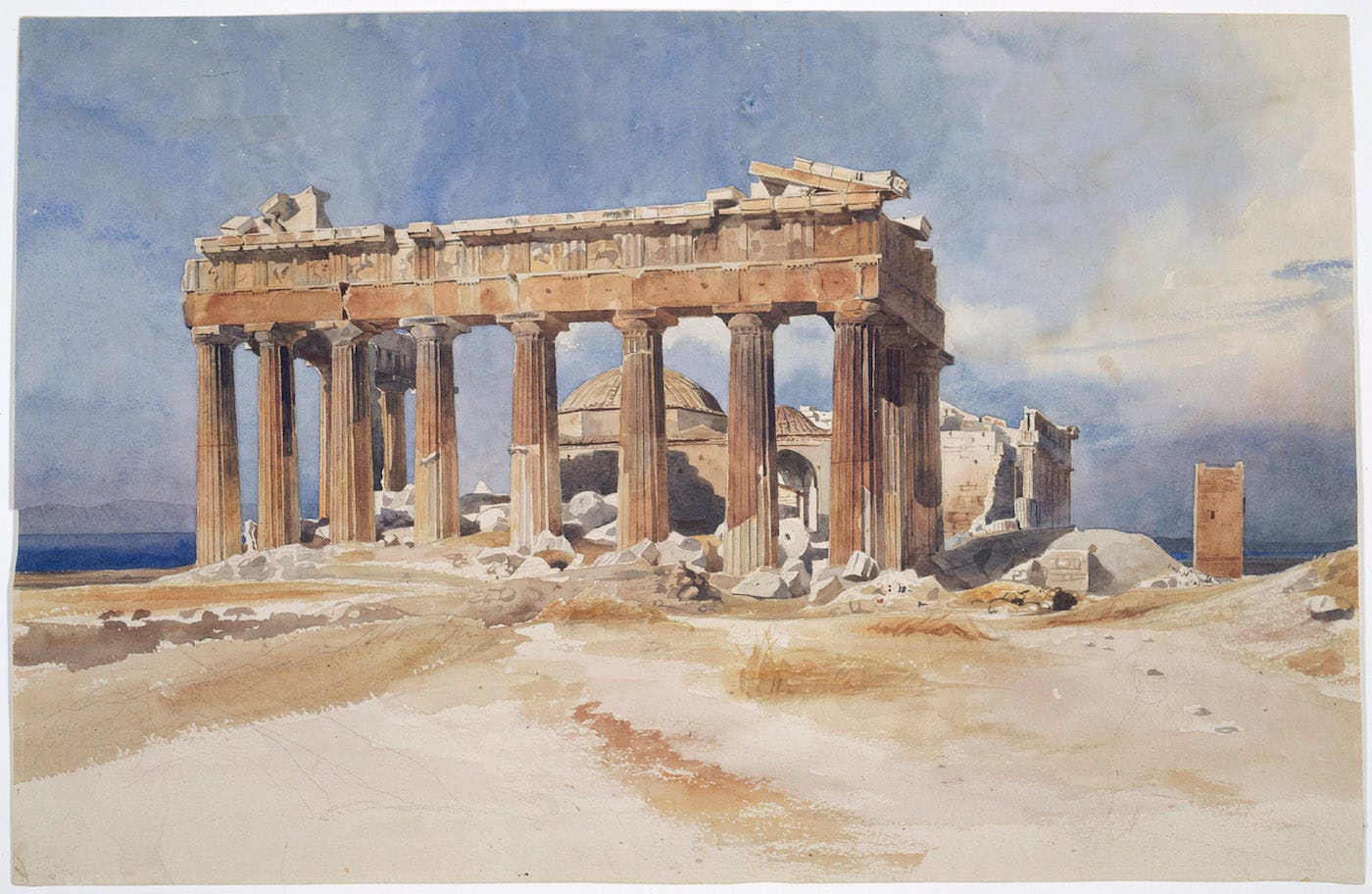

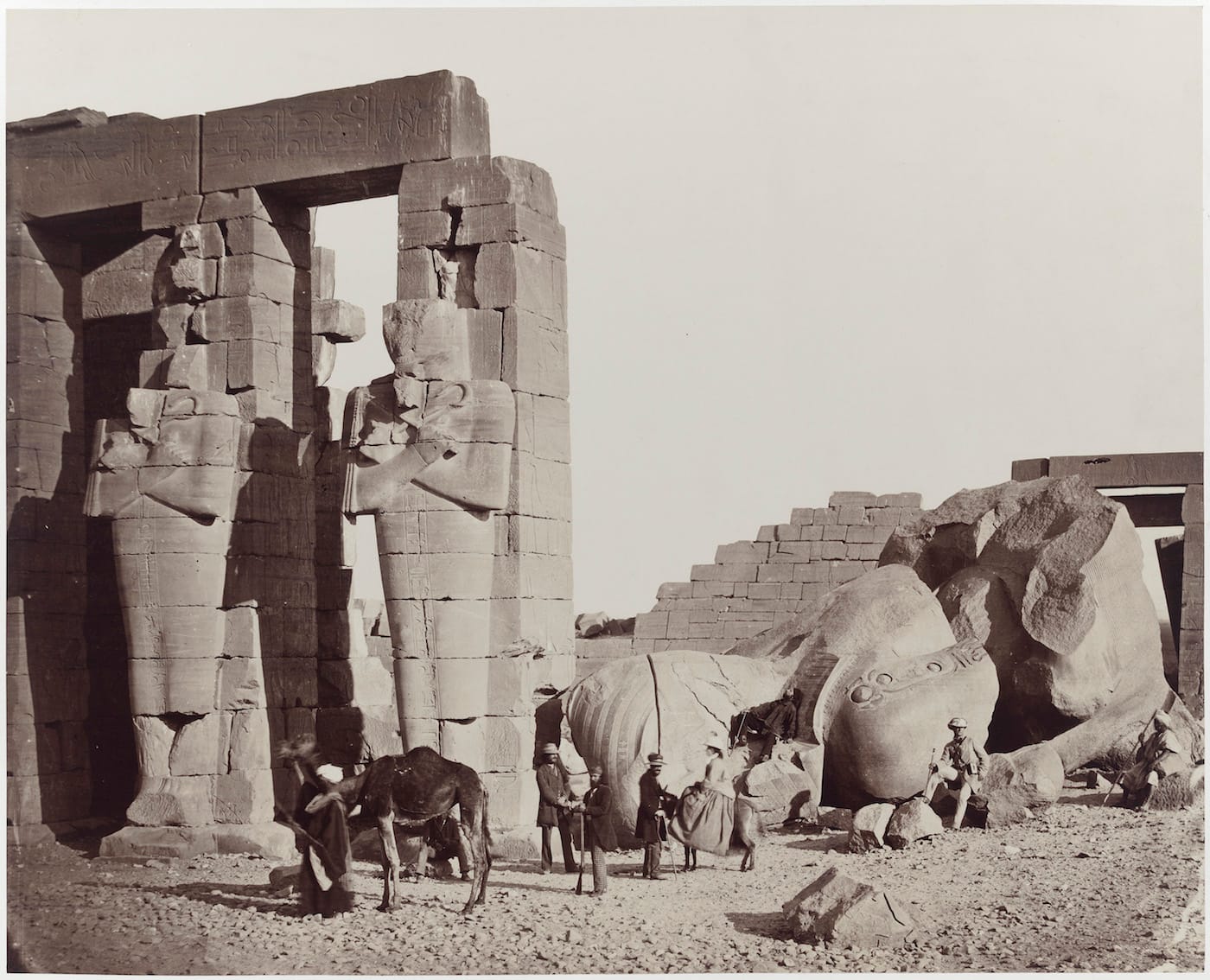

Other images, like an 1857 photograph by Francis Frith of the “Fallen Colossus of Rameses” fixate on the monolithic ruins of Egypt and their toppled giants. Yet there are reminders these are not static places left to futilely cry out, to borrow from Percy Bysshe Shelly, “My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!” The very act of creating these works shows a continued human interaction, even if the once great civilizations have collapsed. Nestled in Charles Gleyre’s vibrant 1834 watercolor of the Parthenon, for instance, is a small mosque between its columns, a sacred space torn down later in the 19th century. And it’s impossible to consider ruins and destruction in 2016 without the shadow of ISIS, which casts over the quiet 18th and 19th-century depictions of Palmyra.

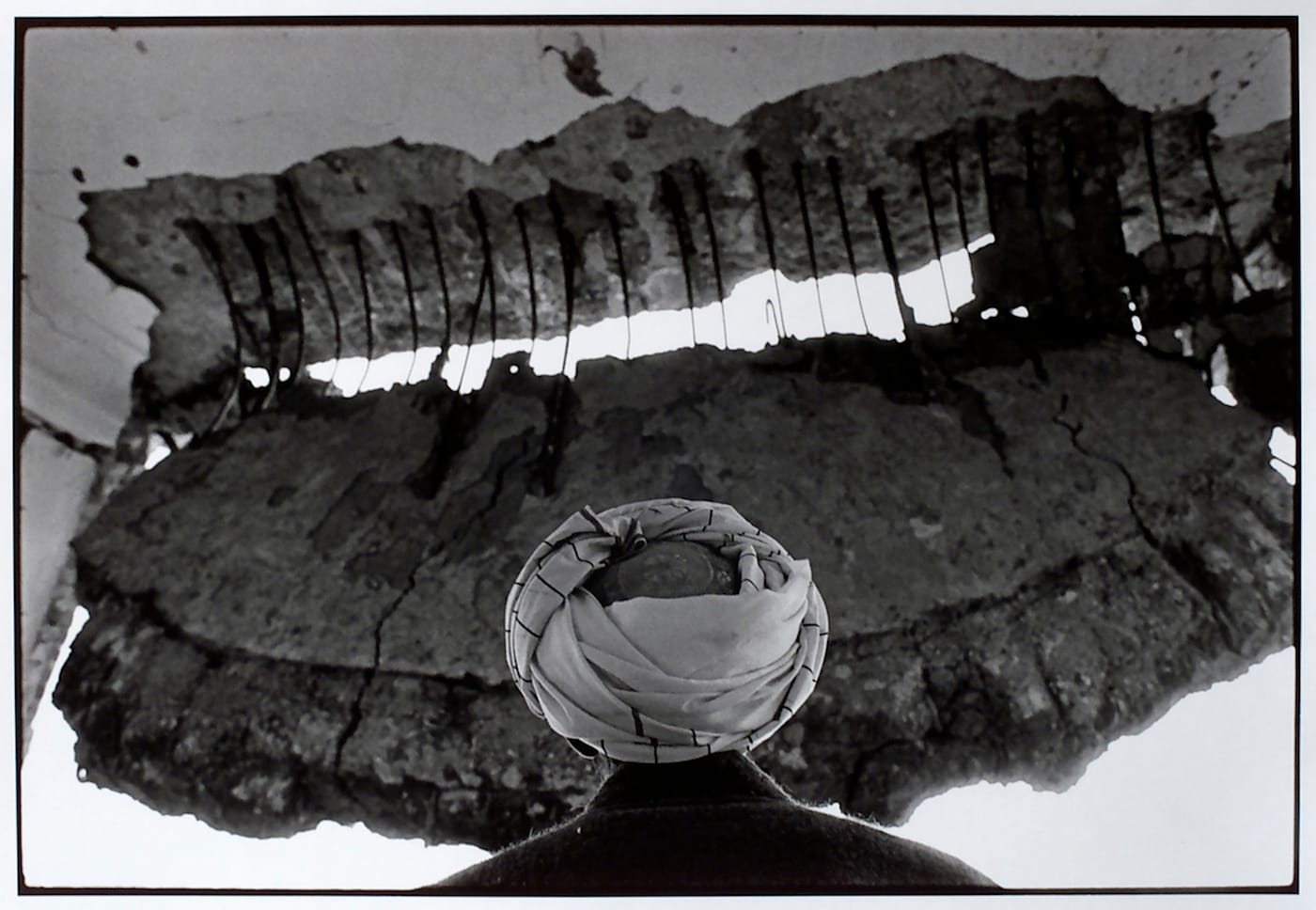

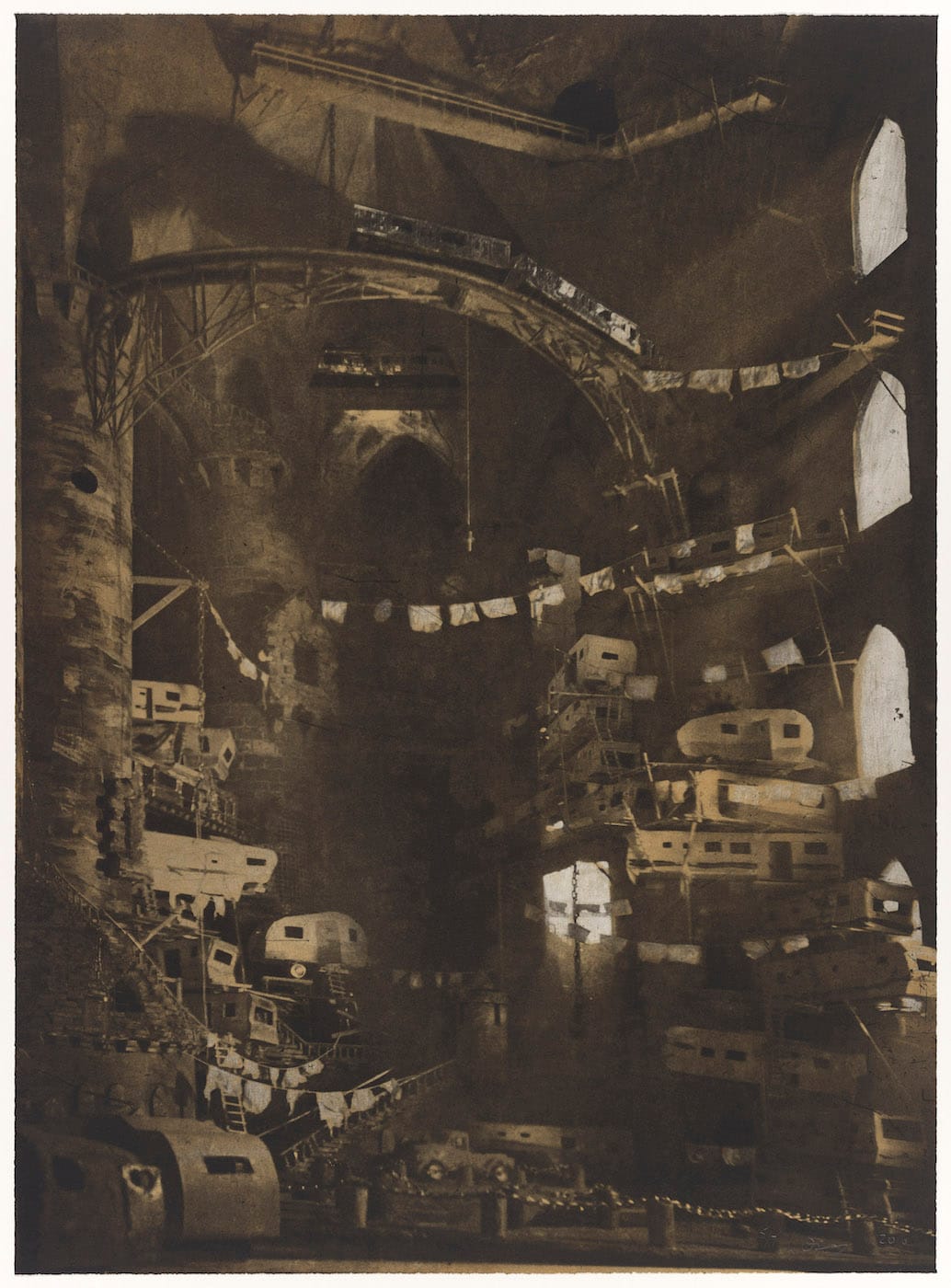

Contemporary work like James Nachtwey’s 1990s photographs from ruins in Kabul, and Lothar Osterburg’s 2010 “Vaulted Trailer Park” that positions stacks of caravans beneath stone arches, show artists continuing to grapple with the vulnerability of cities. Because these expressions are more about the cities than the people, or else this would be an exhibition of scattered bones. These are architectural triumphs that could not move with shifting populations and climates. Whether with the anxiety of the Industrial Age, or our current growth of high rises, they continue to be a portal for comprehending the future by acknowledging our fragile past.

Ruined: When Cities Fall continues through October 23 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (465 Huntington Avenue, Fenway/Kenmore, Boston).