The Contemporary Relevance of Palestinian Tatreez

“When people wear Palestinian embroidery, it’s not just decorative. It's beautiful, of course, but it is saying something,” says author Joanna Barakat.

On November 4, 2025, Election Night in New York City, artist Rama Duwaji joined her husband, mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, on his victory stage. The 28-year-old was wearing all black, but her top appeared subtly textured. It was laser-etched with a pattern that recalled classic tatreez, the ancient and celebrated style of Palestinian embroidery.

“She’s making a powerful statement by wearing that,” said Narrative Threads: Palestinian Embroidery in Contemporary Art author Joanna Barakat about Zeid Hijazi’s “Frequency Top.” “When people wear Palestinian embroidery, it’s not just decorative. It's beautiful, of course, but it is saying something.”

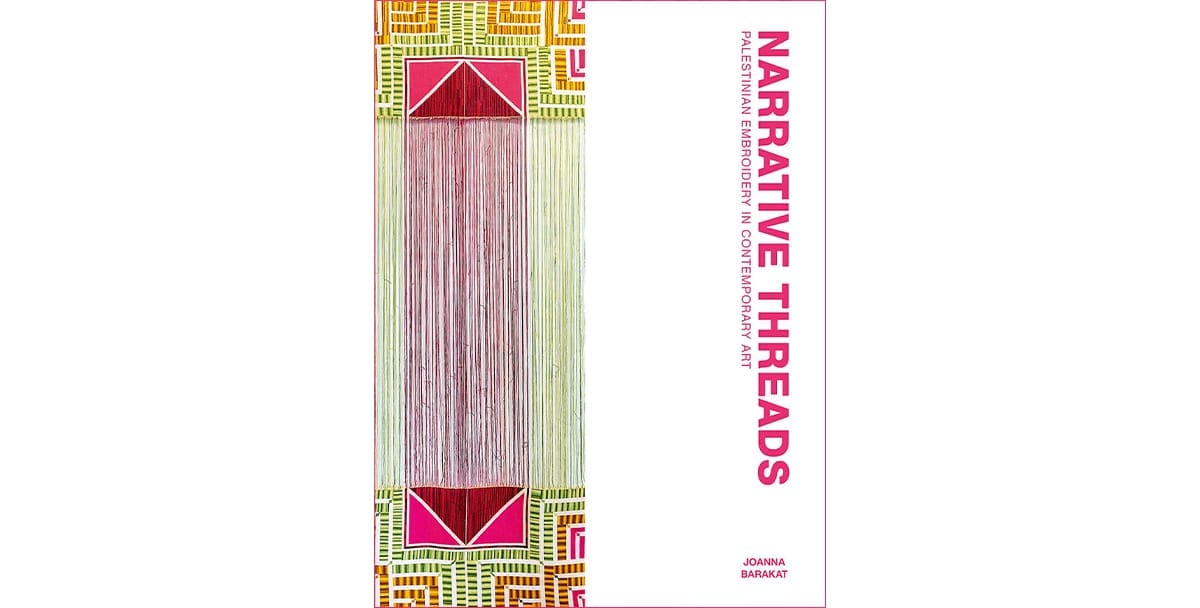

Narrative Threads is Barakat’s comprehensive look at the tradition of tatreez — its meaning, its influence, and its appeal. Published by Saqi Books, it takes a historically undervalued art form (embroidery and textiles are often written off as feminine-coded “crafts”) as an entry point into a historically undermined political struggle. Rather than only looking to the past, though, Barakat is interested in the art form’s current technical and symbolic uses across a range of practices.

“When you look at artwork made by Palestinians, you are going to learn so much about Palestinian experiences and Palestinian stories — those of the artist, and those the artist is depicting or discussing,” Barakat told Hyperallergic on a call from her home in Abu Dhabi. For example, did you know that in 1980 Israel banned the Palestinian flag? The mere use of its combination of colors in a public forum could be reason for imprisonment or steep fines. So Palestinian women began to stitch dresses and thobes in subtle combinations of red, green, and black, preserving a message the freedom fighters would not forget then, or today.

The book provides this history, but it also functions as a kind of almanac for the state of tatreez today by featuring more than 200 works by 24 established and emerging artists, all of whom Barakat interviewed. “It was really important to me that there were direct quotes. I wanted them to talk about their work, and I wanted them to speak about the ideas and what mattered to them, and what they wanted to share with the viewer.”

The images include portraits of women under olive trees or in orange fields in Jaffa by Sliman Mansour, who co-founded the League of Palestinian Artists; collages of Gaza landscapes from Hazem Harb; manipulated archival photos from Sary Zananiri that question “how archaeological or ethnographic knowledge is generated”; the kaleidoscopic floral prints of Steve Sabella; and the colossal embroidery installations of Samar Hejazi, whose work is shown on the book’s cover.

Barakat, who was born in Jerusalem and raised in Los Angeles, is an artist herself. She began researching the relationship between textiles and her homeland while working on her painting “Heart Strings” (2017). In it, she depicts herself stitching a Palestinian motif onto the skin of her chest, embroidering cotton thread directly onto the canvas. She went on to lead tatreez workshops and to create the social media community The Tatreez Circle.

“This medium [of embroidery] provided me with a sense of connection to Palestine and to being Palestinian that no other medium had,” she explained. “I grew up far from Palestine. My Arabic is sadly terrible. This forged a closeness because being able to embroider meant I could speak that language, just like my ancestors may have done.”