The Design Battle to Sell, and to Stop, Smoking

In terms of breadth and controversy, two 20th-century advertising campaigns are almost unrivaled: the drive to sell cigarettes and the backlash to get people to stop smoking. Selling Smoke: Tobacco Advertising and Anti-smoking Campaigns at the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library at Yale

In terms of breadth and controversy, two 20th-century advertising campaigns are almost unrivaled: the drive to sell cigarettes and the backlash to get people to stop smoking. Selling Smoke: Tobacco Advertising and Anti-smoking Campaigns at the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library at Yale University presents these dual crusades side-by-side.

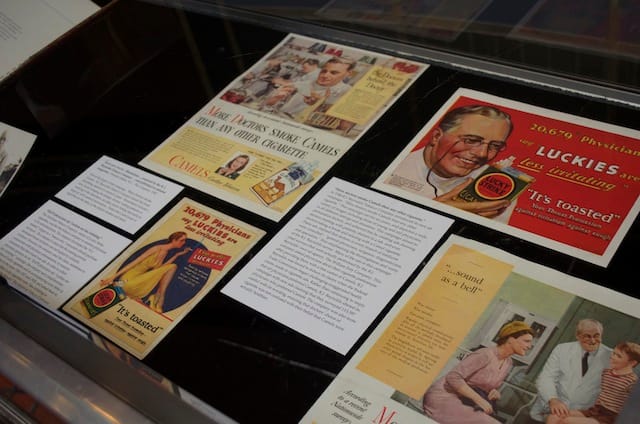

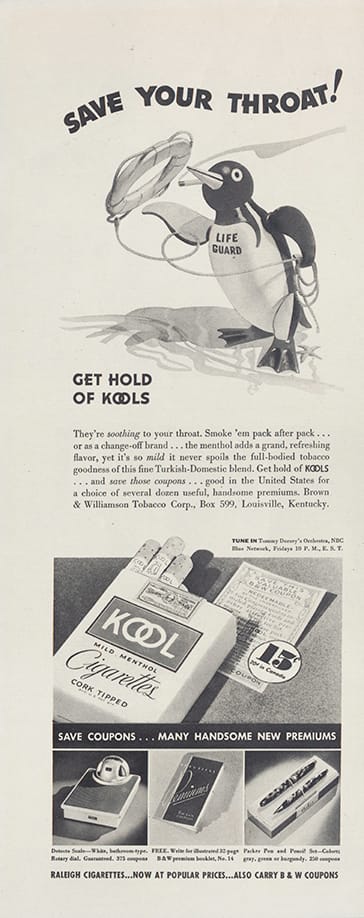

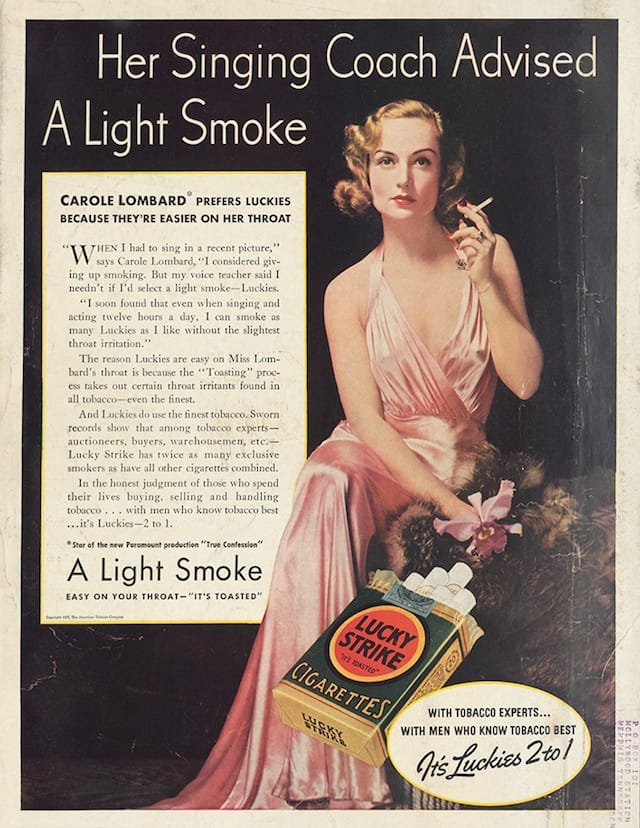

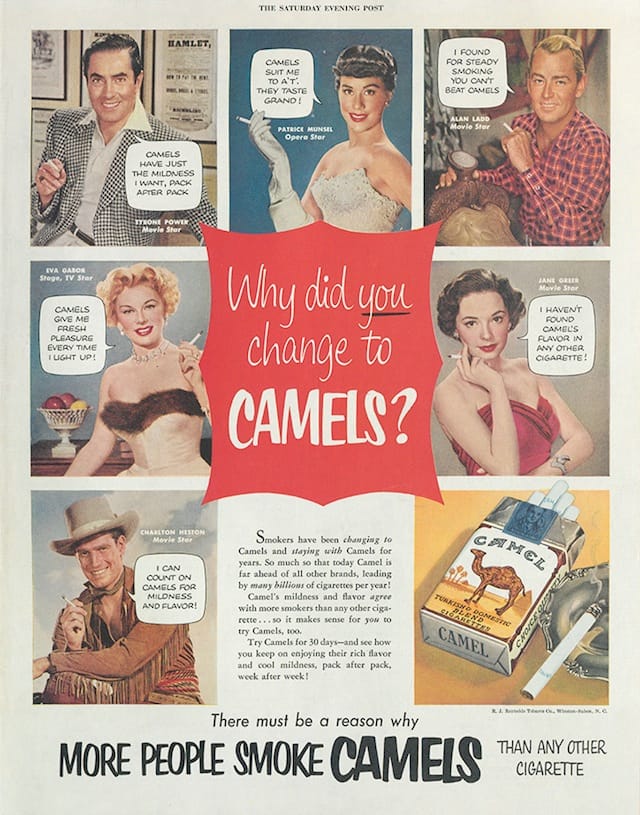

The smoking ads are displayed in glass cases in the Cushing Rotunda, while the anti-smoking posters look down from the walls. Sourced from the the William Van Duyn Collection at the Medical Historical Library (now digitized in conjunction with the exhibition), much of the eager ephemera has doctors, celebrities, beautiful ladies, and even Santa offering a taste of tobacco. The sterner awareness posters from public health organizations and US Surgeons General emphasize the detrimental dangers of those same products. Today the old ads with the Kools cartoon penguin urging viewers to “smoke ’em pack after pack” seem almost comically laissez-faire about health concerns, but it wasn’t easy to shake smoking advertisements’ grip on media.

In the coinciding online exhibition, Yale chronicles the steep rise and gradual fall traced by Selling Smoke. In the early decades of the 20th century, cigarettes were marketed to women as a reflection of slowly liberating societal standards, coupled with dancing, dating, and shortening dresses. Advertisers tapped patriotism during World Wars I and II. Things also started to get more competitive in the 1930s, when the first studies were released on the dangers of smoking; in response, both Camel and Lucky Strike incorporated doctors into their ads, as well as advice on smoking to help the nerves and digestion.

In the 1960s, nonprofit advocacy groups such as the American Cancer Society finally sparked the real rise of the anti-smoking movement. Celebrity endorsements were banned in 1964 (leading to the substitution of “ordinary folk,” and the endurance of the Marlboro Man), health warnings added to cigarette packs in 1965, radio and TV advertising stopped in 1969. As Yale states: “Since 1964, smoking rates have dropped from 42 percent of adults to 18 percent.”

With the exhibition presented in Yale’s medical library, there’s a definite emphasis on the health crisis spurred by the ads. Yet they’re also interesting to look at in terms of visual marketing and graphic design of the 20th century. Society needs a reason to adopt any product, whether vice or virtue, and Selling Smoke displays how cigarettes were precisely presented at every angle to form a national habit.

Selling Smoke: Tobacco Advertising and Anti-smoking Campaigns continues at the Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library at Yale University (333 Cedar Street, New Haven, Connecticut) through August 12.