The Design for 2 WTC and the Dangers of Building Neighborhoods in the Sky

It’s one thing for an architect to invoke a low-rise historic neighborhood on the mega-scale of a high-rise office tower, but it’s quite another to imagine that an office building can actually embody the authentic neighborhood that surrounds it — and not merely the spectacular simulation of said nei

We, the quasi-entitled, live comfortably amid gut-wrenching gut renovations, tear-downs converted into luxuriant build-ups, tautological street-infrastructure projects inspired by Samuel Beckett (digging holes, filling holes, digging up the same holes again), prices through the roof, a baby boom, nanny armies, bespoke dog walkers, and other potent signs of accelerated fabulousness. More real than reality: unreal real estate in downtown Manhattan.

Yet we persist, undaunted by hyper-accelerated urban redevelopment — perhaps epitomized by the new Herzog & de Meuron ultraluxe glass condo tower at 56 Leonard Street in east Tribeca. In concept stage, at least, their design imparted a playful structural dynamism, but now that the building is reaching completion, it seems to have been dumbed down into a run-of-the-mill North Miami Beach residential tower. Another lost opportunity? Or simply a zone- and scale-transgressing extravaganza that should never have been erected in the first place?

Architects, developers, and politicians invariably do the design-for-expediency trade-off tango, a dance of compromises that occasionally results in architectural miracles but more often generates cookie-cutter buildings with hotel-like amenities — and the occasional poor door just to rub salt in the wound — that land in our cities with the dull thud of a pallid satisfactoriness. These days, however, just a hint of innovation seems to act as a sufficient tonic to the pervasive sense of melancholy brought on by buildings of soul-crushing mediocrity. All in all, we seem to be resigned to taking what little we can get in terms of the redesigning of our city, even if this means that our sense of place is becoming displaced into an abiding sense of nonplace. Why anyone would want to spend big bucks to live in a city increasingly characterized by nonplaces — a city that may be reaching the tipping point of population density, particularly downtown — is anyone’s guess. Maybe it’s just becoming more difficult to distinguish nonplace from place?

Two new Manhattan projects — the tetrahedron luxury rental at 625 West 57th Street (currently under construction) and the apparently non-Euclidean stack that will be 2 WTC (in concept stage) — have been designed by BIG, the firm led by Dane Bjarke Ingels. Probably the hottest young architect on the scene right now, Ingels seems to be attracted to the notion that architects still have some degree of responsibility to invoke context/place, i.e., that place still has a place, so to speak, in the nonplace of our post-neomodernist cities. Skyscrapers and towers are part of the DNA of the modern metropolis — embodiments of capital and power, facilitated by trade-offs between private and public sectors, and occasional beacons of innovative, progressive design. In the second decade of the 21st century, nearly 15 years after the destruction of the World Trade Center and just months since the completion of 1 WTC — itself a passable yet uninspired tower that is a monument to design compromises and too many chefs in the master-planning kitchen — another opportunity has arisen from the ashes of that paradigm-shifting day. And like an architectural superhero (perhaps Thor’s distant cousin?), it seems as if the sky has opened up and Ingels has thunderbolted to the rescue with his design concept for 2 WTC.

Larry Silverstein, who controls the site, had apparently struck an agreement with Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp and 21st Century Fox, both of which were to be headquartered in the lower half of the tower, until Murdoch recently decided against relocating the companies to the 2 WTC site. Ingels replaced Norman Foster on this high-profile project, and he has been outspoken about his desire to produce a building that is deeply contextual — i.e., responsive to the memorial, to 1 WTC, to the phantom limbs of the original twin towers, and, in particular, to the historical district of Tribeca. In broad conceptual terms, the desire to allude to context and history may be salutary, yet there is also some reason for trepidation: it’s one thing for an architect to invoke the distinct scale of a low-rise historic neighborhood on the mega-scale of a high-rise office tower, but it’s quite another to imagine that an office building can actually embody the authentic neighborhood that surrounds it — and not merely the spectacular simulation of said neighborhood. Ingels suggests that the slightly off-kilter stack of rectilinear volumes will not only invoke this contextual vernacular, but that each stack element will function as a distinct, flexible ecosystem that can be tailored to the needs, uses, and programs of the client. In other words, employees will not merely labor in alienating workspaces, but will belong to a neighborhood of workers in the sky: the “lifestyle community” of corporate employment. The workplace as privileged neighborhood? Reading the Ingels design on metaphorical terms, to me it symbolizes not the potential harmonization of older human-scaled structures with newer post–human scale megastructures in our cityscape, but rather their basic irreconcilability. Of course, such disparities in scale — often brought about by peculiar zoning allowances — are increasingly in evidence throughout New York. Admittedly, when I first saw the Ingels design, it brought to mind a gargantuan, bulked-up version of SANAA’s New Museum building on the Bowery.

Just as Ingels would like to somehow signify early-20th-century neighborhood charm within an early-21st-century office tower, his design for Google’s new campus in Northern California attempts to engender an interpenetration of the contextual “natural” landscape and the workplace/space, producing what might become a kind of quasi-organic, biosphere-inflected workscape. These projects indicate the same kind of combinatory impulse: for 2 WTC, weaving together the space of work and the space of neighborhood, and for the Google campus, weaving together the space of work and the space of nature. In both instances, design is an instrument with which to blur categories and experiences, or at least to produce a persuasive simulation of this blurring. It’s one thing to introduce nature into the workspace, but quite another to displace the vernacular codes of a neighborhood into/onto an office tower — the latter creates the impression that the architect is sensitive to place, even though what’s being proposed is closer to postplace. But since communities/residents have precious little say in what private developers and their hired architects do, we are reduced to holding our collective breaths and hoping for the best.

One hopes that 2 WTC will not merely become a signifier of Downtown’s final, triumphant, ecstatic financialization. Who needs authentic neighborhoods when simulated neighborhoods can be generated as/within residential and office towers? And who can distinguish between the real and the simulation at this point anyway? It almost goes without saying that a brand new simulated version of a neighborhood is sexier, and far more millennialesque, than the existing neighborhood that served as the model for the simulation. I’m being coy, dear reader, but you get the point. In the future, when I look up at 2 WTC, will I see a new, improved, workspace version of… the neighborhood?

We appear to be in the midst of an accelerated towerizing — and, in certain instances, mega-towerizing — of Manhattan (and Brooklyn, too). My use of the term “towerizing” is not meant to be confused in any way with terrorizing, of course. Although, come to think of it, it is a bit terrifying to consider the stratospheric prices for sky-kissing condos, and to acknowledge that such buildings evince a desire for a separate enclave of class-based living/lifestyle perched on Olympian heights, far removed from the teeming mass of mortals that make up the urban dross. This is not an entirely new phenomenon historically, yet we seem to have entered into a hyperbolic expression of this tendency, wherein floor-through palaces in the sky are the bejeweled testaments to the materialization of global capital. Think of it as Fritz Lang’s Metropolis on financial steroids, but, regrettably, without the highways in the sky that would in fact now be a pragmatic infrastructural response to the overcrowding of streets and sidewalks in downtown Manhattan.

If you build vertical towers, this produces increased urban density down at street level, yet there seems to be little thought about how to deal with this density on an everyday, lived basis. Traffic is our infrastructure, but perhaps the most bizarre example to date of this lust for mega-towers has not even been envisioned for a city, but rather within the quaint town of Vals in the Swiss Alps, where Thom Mayne/Morphosis won a hotel competition with a design featuring a mirrored, slenderized, 381-meter-tall needle-tower. The dream here, apparently, is to reach the towering heights of mountains, because that’s where gods, power, and ultra-customized hotel services dwell. Do megatowers presage the emergence of megacities? Or are megatowers a necessary element of megacities? Let’s hope this is not the future for Vals. And then we have China’s planned Jing-jin-ji megacity around Beijing, which would comprise a population of more than 130 million souls, covering an area of over 200,000 square kilometers, dwarfing a place like New York. The emergence of what might be a new kind of city-state.

But to get back to the point, since it is, at least ostensibly, the redevelopment of Ground Zero that we are discussing here: 13 years ago I wrote “A Strangely New New York: From Viewing Platform at WTC/Ground Zero to Prada Epicenter Store.” First published in the March/April 2002 issue of Flash Art, and subsequently revised for my 2013 book, Art Is a Problem, the essay offered a comparative analysis of these two new architectural-urban projects. Like many other residents of NYC, I witnessed the attacks and the collapse of the WTC towers, and I harbored conflicting thoughts about what should be done to heal the wound, so to speak:

Regarding the appropriateness of the Viewing Platform, this is an issue — moral, ethical, and spiritual — that each of us has to reflect upon. Many people — on regional, national, and global levels — want to, and will, make pilgrimages to Ground Zero. The Platform does help to regulate the flow of visitors through lower Manhattan, even though its existence, paradoxically, may attract more people. At the same time, no one wants to be perceived as linking the Viewing Platform to a broader marketing campaign to revitalize New York’s tourist economy; this would be distasteful. (And what of the family members who lost loved ones in 9/11: how do we gauge their various perspectives?) New Yorkers are concerned, legitimately, about escalating voyeurism and spectacle, particularly since bodies are still being unearthed from the site. At the same time, given that live and recorded images of Ground Zero have been on television continuously for months, and that the site exists for most people as pure media event, the Viewing Platform does, at the very least, create the opportunity for another kind of experience. This is all a preamble, of course, to the public debates that will heat up regarding the actual redevelopment of the WTC site, and the design of a permanent memorial.

1 WTC is currently the tallest building in the United States and the third tallest in the world; Dubai has the highest. Massive tower projects are under way in China, Russia, and elsewhere. Maybe this is just an extreme version of Le Corbusier’s dream of cities in the sky: cities in the rarefied air of the upper stratosphere. Evidence: Billionaire’s Row in and around 57th Street. For instance, Rafael Vinoly’s 432 Park Avenue supertower stretches 1,396 feet to the heavens like an elevator shaft with windows, making it the tallest residential building in NYC, visible from almost everywhere. This megastructure heralds the pending arrival of more supertowers in this urban node, unless our mayor can somehow thwart the onslaught, which seems unlikely. This is urban acupuncture taken to an absurd limit; these super-expensive needle supertowers may burst the city before the real estate bubble bursts. Perhaps one day, New York’s underclasses will all live under the shadows of the superrich’s supertowers, as in certain neighborhoods in Mumbai. How soon until we arrive at that post-cosmopolitan, dystopian future here in NYC?

In the Financial District, perhaps as a riposte to Frank Gehry’s “New York” torqueing rental 76-story supertower at 8 Spruce Street, a Robert A.M. Stern condo tower is going up: 30 Park Place, owned by Silverstein Properties and marketed as Four Seasons Private Residences. Here’s an excerpt from the building’s description on Stern’s website: “Sharing a city block with the Woolworth Building, Cass Gilbert’s iconic 1913 skyscraper, 30 Park Place, will combine a 189-key five-star Four Seasons hotel with 157 top-end condominium apartments in a slender 82-story tower that will become an important landmark among the constellation of towers in Manhattan’s Downtown.” Enough said? Well, perhaps just one thing to add: Although this tower is still being constructed, it already reeks of ersatz historicism and a kind of deadly (and deadening) self-importance. Worse still, it’s drab on a gargantuan scale. Taken together, the Gehry, Stern, and Herzog & de Meuron towers can be understood to symbolize the transformation of lower Manhattan into an amalgamated cartography of speculative, luxury-lifestyle capital.

When Ingels speaks of how the scale and vernacular of downtown’s historical districts influenced his design concept for the WTC 2, we may be seduced by his desire to use the neighborhood’s DNA to grow a building that, he implies, will challenge the archetypal office tower — perhaps this is his way of acknowledging the need for preservation. Or perhaps it is his way of suggesting that the preservation of historical architecture — its language, scale, proportions, and embedded urban histories — will eventually become an anachronism, because it can be invoked or assimilated as codified vernacular, as branding device, within the form of new buildings. Is this Ingels’s way of proposing a kinder, gentler, and smarter version of postmodernism, or post-historicism?

A building that is a shape-shifter, that is continuously adjustable, mutable, and flexible, that can be designed to be structurally responsive to its urban environs, reshaping the city that in turn reshapes it, is a seductive fantasy. Ingels seems to be attracted to the dialectical relationship between the unitary building and the multiplicities of urban space that surround it. His architectural language suggests flexibility and organic mutability, an approach — not entirely unlike Zaha Hadid’s — that can generate pleasing visual and spatial effects, particularly in relation to the literal immutability of monumental urban edifices and megastructures. There is something magnetic, at least at the level of style and the image of the cityscape, about seemingly post-rational, post-Euclidean, sculptural architecture in the midst of assembly-line neomodernist rationality. Yet I think this is more of a spectacular theater of formal ingenuity and engineering pyrotechnics than it is a fundamental rethinking of the role of architecture and architect in our cities. Historically, and in the present, we’ve observed suggestions of movement, mutability, and urban responsiveness within aspects of designs by Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, Niemeyer, Gaudi, Gehry, Libeskind, Hadid, Koolhaas, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, and Mayne/Morphosis, among others. These impulses suggest a different kind of morphological life for architectural form that invokes fluidity and movement, particularly in relation to the putative rigidities of Mies van der Rohe and his high-modernist progeny (although there can be reflected movement in/on the glass curtain). Superstudio and Constant dreamt of a different kind of city beyond the rational expressions of urban capitalism, wherein megastructures would, ironically, unite urban differences while also opening up the possibility of mutable, post-capitalist city spaces, becoming a kind of negative utopia designed to consume the dystopias of rationalized, capitalist urban space. This never came to pass, of course, perhaps because real megastructures lend themselves all too easily to economic and political power. Luxury supertowers are our post-utopian megastructures.

But I have a sense that Ingels would like to throw a bit of a curveball at the pandemic lust for phallic needles poking at the sky. Ingels has nicknamed his West 57th Street rental building a “courtscraper,” which apparently is meant to signify the dovetailing of elements of a European courtyard building and the scale of a skyscraper. Currently under construction, the tetrahedron appears to be swept away from the West Side Highway as if by the Hudson River’s tides. The building has a kind of horizontal verticality, exuding a dynamic, neofuturistic spatial-structural elasticity that distinguishes it from the surroundings, yet also suggests a playful relationship to place. It seems to have a sense of humor about itself, which is refreshing. But I also have the impression that the building would be more comfortable on the Santa Monica beachfront than in Midtown Manhattan — though maybe that’s part of Ingels’s point.

The problem with innovative buildings is that they eventually become static monuments to their own architectural ingenuity, which, admittedly, is still preferable to the vast majority of buildings that memorialize their own mediocrity. It’s questionable whether New York was ever really a delirious city or an event-city on architectural and urbanistic terms, but if there is delirium today, it is the delirium of excess capital, some of which has been generated by an overheated real estate market that threatens to transform the city into a vast gated community of luxury condos and rentals. And while I suppose I prefer that someone like Ingels is the recipient of this excess capital as opposed to some hack, I’m more committed to the idea and practice that significant amounts of capital (political and economic) need to be invested into communities that are being pushed out of their neighborhoods by the forces of unrestrained gentrification and inequitable urban development. New York City needs not only more affordable housing, but an affordable urban ecosystem — and both seem to be slipping further out of reach, the current Mayor’s efforts notwithstanding.

Empty space, and available sky-space, have always seemed to induce horror vacui and kenophobia in property owners and real estate developers. After 9/11, this tendency was intensified due to the desperation to rebuild what had been lost, to fill the void, to prove that the United States would not capitulate to terrorisms. And so, after more than a decade, we have 1 WTC, a half-baked structure that reads like textbook architectural compromise. It is adequate but inelegant. It doesn’t even work particularly well on its own terms, because its terms are internally inconsistent. The most effective characteristic of 1 WTC may be its oblique allusion to the skin of the original Twin Towers. In all other respects, however, it appears to be the result of a design-by-committee process, an inert mélange of stillborn ideas, and a monument to missed opportunities. But there it is, nonetheless standing its ground, dumb and defiant, utterly humorless (despite being topped with an immense light saber) and oblivious to anything we might say about it. It’s like an architectural bully hulking at the bottom end of Manhattan. But at least there’s an observation deck.

Perhaps Ingels senses that something is amiss with 1 WTC, and sees 2 WTC as an opportunity to inject a bit more adventurousness into the post–Ground Zero context that had already devolved from master plan to mishmash, if only to distract us from the mundaneness of 1 WTC. Although it will be difficult to compete with Santiago Calatrava’s new transportation hub, which invokes the beautiful skeleton of a colossal extraterrestrial spaceship. My understanding of the Ingels design is that when the building is viewed from one angle, a phantom limb of one of the original WTC towers will be connoted — the continuous surface side of 2 WTC somehow mirroring 1 WTC, and the specter of the Twin Towers reconstituted, in a deft act of perceptual conjuring. From the other primary perspective, we will observe the irregular stack of boxes, ascending like a stairway to architectural and — Silverstein hopes — financial heaven.

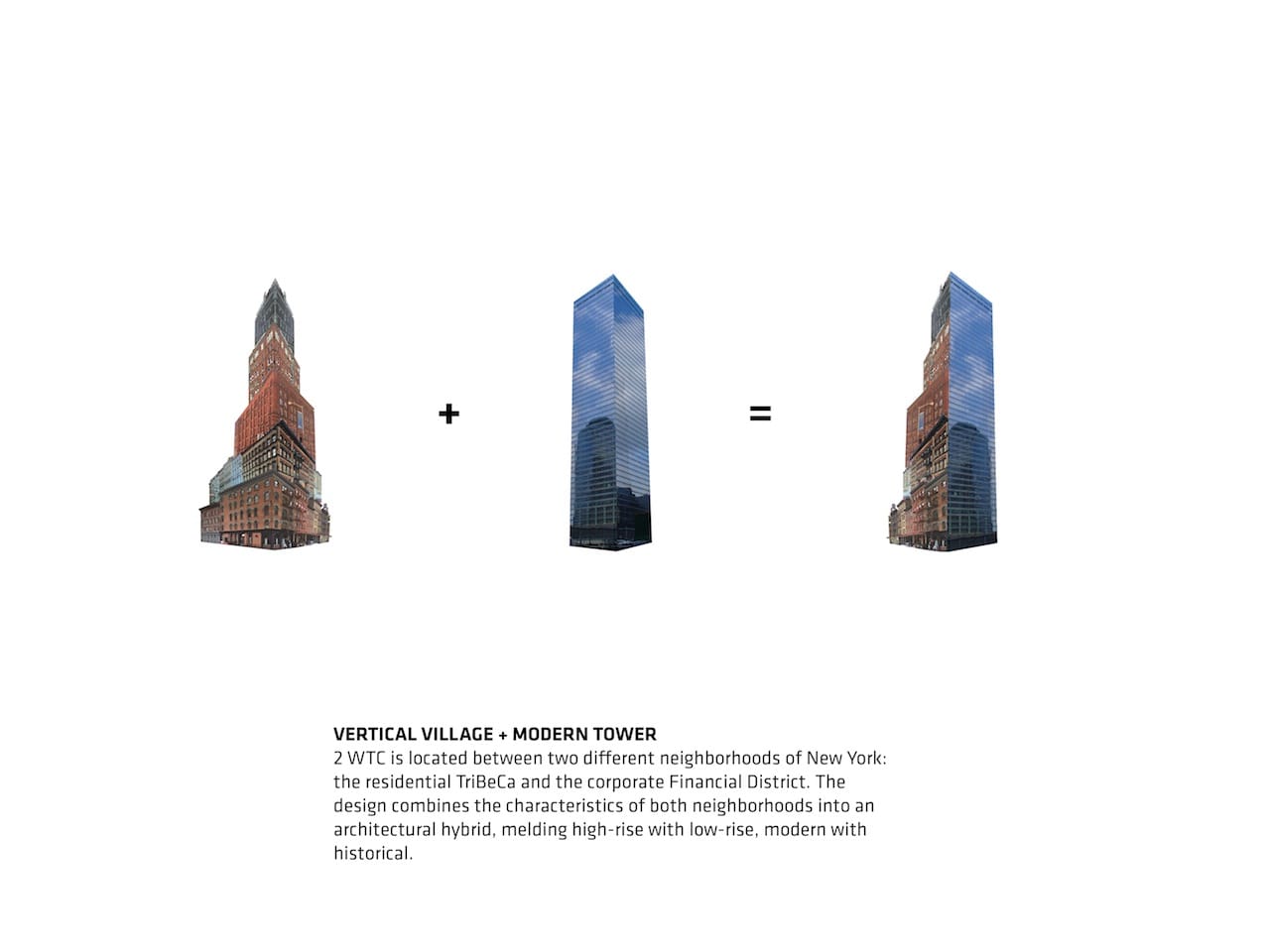

Whereas Le Corbusier wished to produce streets in the sky, Ingels appears to be trying to engender neighborhoods in the sky with this design. In one of his explanatory diagrams for 2 WTC, he promotes a simple formula: “Vertical Village + Modern Tower = 2 WTC.” Perhaps invoking MVRDV’s use of the vertical village concept in rethinking Asian cities, Ingels would like to fuse together the more intimate historical scales of the pre- or early modern urban village with the seemingly unstoppable mega-scales of 21st-century supermodernism into a hybrid that probably would have given Jane Jacobs heartburn, but might have been heartening to Robert Moses. On conceptual and formal terms, there is something interesting about how Ingels takes one step backward and two steps forward, while avoiding some of the worst tendencies of postmodern architecture’s kitschy, ersatz neohistoricism, yet there is nevertheless something rather generically corporatist about his 2 WTC design. Beyond alluding to local context in an obliquely codified manner, and even taking into account the sophistication of his design, wouldn’t it be nice to see Ingels engage with a wide range of NYC residents in public dialogues about 2 WTC, instead of merely paying lip service to ideas of neighborhood and community by producing a ginormous hypermodernist corporate simulacrum that seems to usher in the end of any traditional conditions of human-scale density, neighborhood and community? Maybe we have arrived at the cusp of post-human urban density.

Yet the citizens of this city are also Ingels’s clients: we have to live with the buildings too. Of course, this is a ridiculous suggestion that invokes the possibility of a dangerously democratic, egalitarian urban/architectural design process. In terms of the ethics and politics of architecture and urban development, today’s progressive architect needs to rethink the top-down, fait accompli approach and find innovative ways to constructively reach out to the multiple populations (in addition to community boards) that comprise a city, as an integral part of the design process. In other words: during the design process, not after it.

In the end, though, do we really need to fill another void at Ground Zero, regardless of the merits of the architectural design? Yes, some temporary construction jobs will be created, and more office space will be made available. But is this the best we can do at a moment when many in New York City are demanding a more equitable approach to urban development? An approach that deemphasizes the financial center, and instead seeks to redistribute investment capital — and political capital — to traditionally marginalized communities in ways that will not reproduce the inequitable aspects of gentrification? Maybe we should have a citywide referendum. Oh, never mind, I must be dreaming.

As a born and bred New Yorker, I’m still committed to this place; it’s where I’ve lived and worked most of my life, and where my parents died. But is our city still a place? Or is it a nonplace that is on the verge of becoming a postplace wherein the only space left is the space of capital? Maybe we’ve reached a tipping point, and now we need to tip back in the direction of an authentically diverse, equitable cosmopolitanism, and embrace the ethos of inhabiting a complex, shared urbanity: a just city that benefits the many, not only the few.

Correction: This piece originally failed to note that News Corp and 21st Century Fox will no longer move to 2 WTC. We regret the error, and it has been fixed.