The Egalitarian Vision of Nativity Scenes

In all its artistic iterations across millennia, the nativity remains inherently political in its depiction of God choosing to enter the world in marginalized circumstances.

The Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola had been martyred less than two years when the early Renaissance master Sandro Botticelli completed his strange painting “The Mystical Nativity” around 1500. Eschewing the wooden panels on which he normally rendered his compositions, Botticelli’s latest painting was on canvas — the better to roll it up, should its incendiary message anger Florence’s rulers. Indeed, just a few years before he completed the painting, Savonarola, then powerful in the city-state, had been sentenced to death in part for his thunderous edict that Florentines should let the “rich give to the poor, [and] let the churches be stripped of their excessive wealth.” Like all nativities, whether sentimental or censorious, sugary or surreal, Botticelli’s compsoition conveys the central paradox of God being created by a human, and the implications of taking that belief seriously. In all its artistic iterations across millennia, the nativity — the birth of Jesus in a humble manger — remains inherently political. It reveals not just the paradox of divine embodiment, but the radical truth of equality inherent in God choosing to enter the world in marginalized circumstances, thereby declaring the sacred dignity of all human beings and our moral obligations to one another.

The archetype of nativities transcends the Christian account in Luke 2:16 of “Mary, and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger.” The earliest example of the form, discovered by Marco Morelli, director of the Museum of Planetary Sciences in Prato, Italy, in a cave in the Egyptian Sahara, depicted simple male and female figures with a floating infant in between them in red ochre, a star placed above. “As death was associated to Earth in contemporary rock art from the same area,” Morelli told Archaeology Magazine in 2016, “it is likely that the birth was linked to the sky.” Remarkably, this “nativity” was rendered 3,000 years before the events of the gospels. No hypothesis of direct influence needs to be posited — such themes are simply in our collective unconscious.

Among the earliest of artistic representations of the nativity that actually do concern the Bible narrative is another Egyptian piece, a remarkable Coptic Orthodox icon preserved since the eighth century at the Monastery of St. Catherine in the Sinai desert. Rendered in hot wax paint on wood, the icon depicts a dark-complexioned Mary berobed in red, reclining and smiling at her son before a chorus of angels. Other early depictions of the nativity in Christian art, as Gail Paterson Corrington writes in The Harvard Theological Review (1989) present him as “seated on her lap in the position of Horus being nursed by Isis.” Such images of Madonna breastfeeding Christ proliferated first in Egypt and then parts of the Roman Empire that were also familiar with venerating images of Isis and Horus.

There is a central paradox to the nativity: The simultaneously exhausted and delighted icon of Mary is a woman and not a goddess, though she births the God that created her — she is the theotokos, or God-bearer. A similar paradox ensnares Christ Himself, who is both man and God. Even in its most basic forms, then, the nativity subverts hierarchies; it is a mystical statement about the relationship between the sacred and the profane expressed by the 19th-century English Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, who in sprung rhythm evoked she who “Gave God’s infinity/Dwindled to infancy” (1883).

Nowhere is the central paradox of Christianity’s faith in Christ being equally both man and God as apparent as in the crèche, or tableaux representing His birth. As a subject, the nativity dwells in embodiment, of the reality of being a human born between piss and shit, the grotesque and glorious truth of what it means to be a physical being — which doesn’t just tinge the material world with the sacred, but indeed makes the sacred material. As different as the Sinai icon is from Botticelli's nearly a millennium later, the central concern remains the same. The Italian painter's “The Mystical Nativity” spatially delineates the realm of the above from that of the below via the roof of the manger; the nativity itself is the belly button connecting the transcendent to the prosaic, the eternal to the present, the heavens to the earth. As with any traditional crèche, the infant Jesus is swaddled in his straw-filled crib with the blessed mother in her celestial blue robe kneeling in prayer before her son. It encompasses both Genesis and apocalypse, eternity collapsing into the present — which could very well define the symbolic itself. The baby’s swaddling cloth looks like a death shroud, the darkened manger like the cave where the dead Christ’s body will one day be placed. Womb and tomb, death and birth, creation and destruction — all are expressed through the same visual idiom, conveying that which is beyond its literal self. It is the only painting that Botticelli ever saw fit to apply that most intimate of symbols, his signature, in a flurry of black paint.

Botticelli’s signature on this nativity scene represents the application of the individual to the cosmic — such is the nature of any individual representation of the archetypal. Yet within generic confines, there can be marked displays of difference, and the ways in which the nativity has been represented by artists is no exception. The earliest representations of what’s clearly the theme of the Madonna and child — and not just Neolithic cave paintings that evoke that story — are from the catacombs of Rome during the second century, before the canon of the Bible was even finalized. Beneath the streets of the Eternal City is a fresco in the Catacomb of Priscilla, the earliest discovered version of art depicting Mary nursing Christ, rendered in red pigment that can’t help but recall the ochre in that similarly hidden and dark Sahara cave. A full nativity scene isn’t found until three centuries later, among the earliest being the frieze on a sarcophagus lid from the early fifth century in Milan (after the ecumenical councils had already decided issues of Church theology and the Empire itself had converted to Christianity) where the infant Jesus is swaddled while two beasts of the field watch over him, in keeping with the prophecy from Isaiah 1:3 that the “ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib.”

Those elemental images, totemic in their simplicity, gave rise to innumerable variations. In his “Nativity at Night” (c. 1490), now held by the National Gallery in London, the late Medieval Netherlandish master Geertgen tot Sint Jans offers a take that is contemporary to Botticelli. If it is less hermetic in its symbolism, it is every bit as mystical. Drawing from the visions of Saint Bridget of Sweden, in which the infant Christ “radiated such an ineffable light and splendor that the sun was not comparable to it,” Sint Jans depicts the vaguely alien-looking infant in startling chiaroscuro, a burst of radiance glowing forth towards Mary. A similar effect of light in darkness — the great Christmas theme, after all — is explored in ostensibly secular form in the French painter Georges de la Tour’s c. 1640s “The Newborn Child,” held by the Museum of Fine Arts in Rennes, France. In it, an attendant and a mother holding her child are burnished to a glowing, smooth, uniform simplicity and framed by a flickering candle. This is a portrait of Mary, but it’s also a portrait of all mothers. De la Tour’s depiction is less a secularization than a return to the elemental as first expressed in ochre 5,000 years ago.

The nativity, with its expressions of embodiment, paradox, and subversion, can’t help but have political ramifications. The dyad of Mary and child is one of human and God — of the human delivering God into the world, that paradoxical relationship between the divine and the lowly Hopkins wrote of. A turning of the world upside down in its subversions, as well as an embrace of the gritty and grimy reality of matter, a world in which God Himself was born in a filthy stable reeking of urine-soaked hay and animal dung. According to the Slovenian Marxist philosopher Slavoj Žižek in The Puppet and the Dwarf: The Perverse Core of Christianity (2003), the incarnation — which begins with the nativity — represents the “subversive kernel” of the faith, which is “accessible only to a materialist approach.” In the birth of Christ, there is the subservience of spirit to the flesh, of their unity. Furthermore, because this is God who is being born, there is an implicit egalitarian truth to the unity of all who dwell in matter — all of us, in other words, who have bodies.

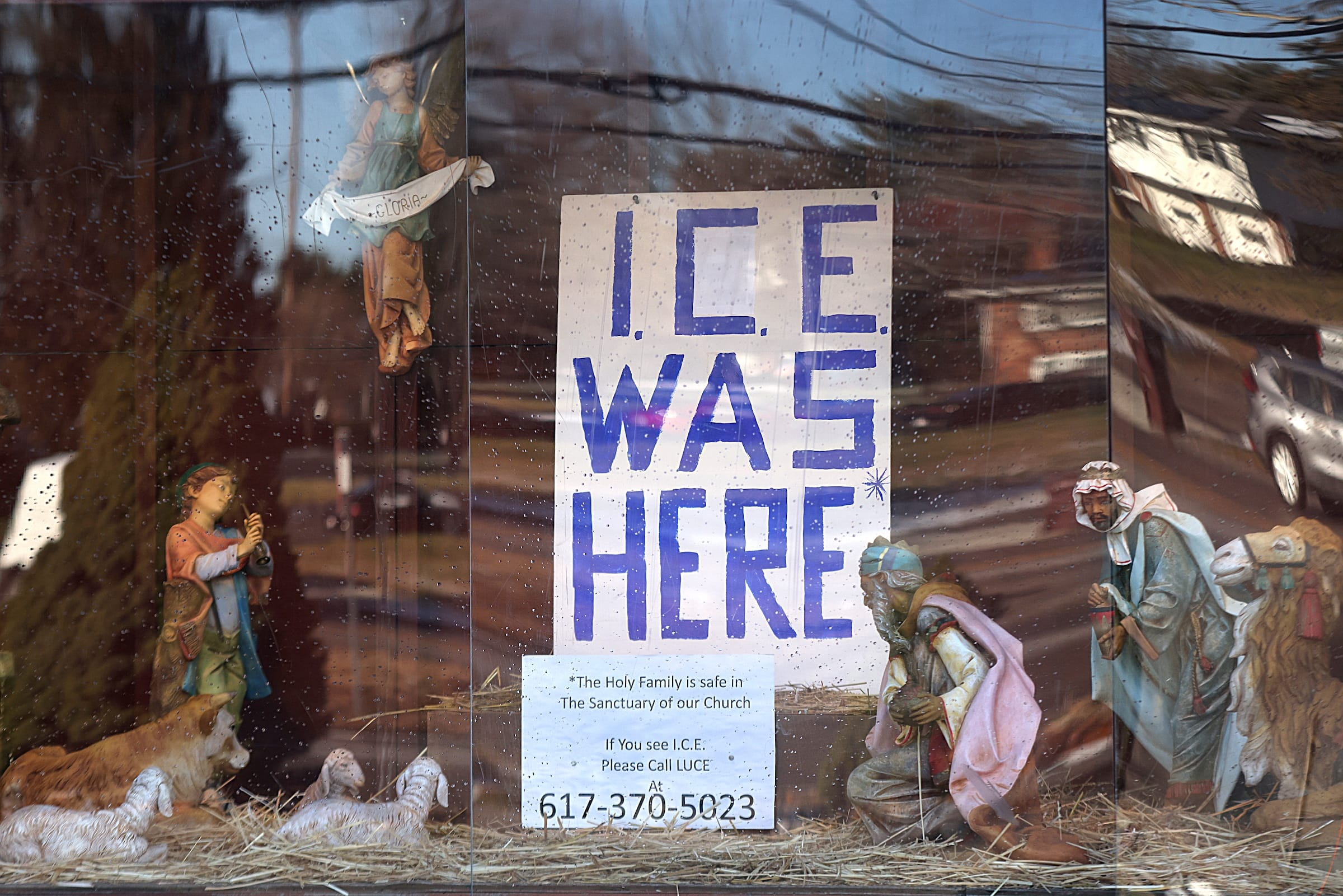

And so the nativity can be used as the most potent of political commentaries. Churches such as St. Susanna Parish in Dedham, Massachusetts, have assembled crèches in which the Holy Family is absent, replaced by a sign reading “ICE WAS HERE,” in reference to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). In Evanston, Illinois, Lake Street Church presents a Mary, Joseph, and Jesus that are zip-tied, the Roman centurions outfitted in the tactical gear of immigration officers. Contemporary artist Benjamin Wildflower, whose work often explores radical politics and faith from an anarchically Christian perspective, crafted a 2018 linocut that imagines a distinctly non-Western Mary as a refugee during the flight into Egypt, the haloed Mother of God prying open a barbed wire fence. Another popular illustration, which goes viral every Advent season, is a family Christmas card originally made by artist Everett Patterson in 2014 entitled “José y Maria.” Here, the parents of Christ are Hispanic migrants outside of a blasted-and-dingy convenience store in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania — Mary wears a “Nazareth High School” sweatshirt. Joseph is on a payphone trying to see if there is room at the motel across the street (some letters are missing in the sign so that “New Manager” reads “New Manger”), while the neon light of “Starr Beer” glows in red and green.

Acting Director of ICE Todd Lyons referred to the nativity scene in Dedham as being “abhorrent,” and castigated the parish priest Stephen Josoma as an “activist reverend.” Of course, the Christian nationalists in the Trump administration, having fully supplicated themselves to the idols of state and capital, are incapable of detecting that subversive kernel in the gospels, or perhaps are unwilling to do so for what it might imply about the state of their own mortal souls. But a nativity is by its very nature political, for it expresses that God dwells in the lowliest, most degraded, and most marginalized of places, that the face of the Lord can be found in the weakest and the most ignored.

What would all these pearl-clutchers and boot-lickers complaining about political nativities think of Botticelli’s c. 1483 “Madonna of the Magnificat”? True to the same radical politics of “The Mystical Nativity,” this work depicts not the birth of Christ, but rather when Mary was visited by her cousin Elizabeth, who was pregnant with John the Baptist. A beatific Christ sits on his mother’s lap, gazing upward at her, his small hand on her arm, as she writes out a line of Latin words in Gothic script. This Mary is no mere vessel, no meek and supplicating virgin progenitor of Christ, but rather an active agent in her own right, penning the words of the prayer known as the Magnificat. “Praise be to God,” Mary writes, who “hath put down the mighty from their seat, and hath exalted the humble. He hath filled the hungry with good things, and the rich He hath sent empty away.” Reactionaries perennially grumble about a so-called “War on Christmas.” That's because it's easier than fully living the implications of the "War for Christmas" — in the most shining truth of the nativity there is no culture war, only a class war.