The Evolution of the Watermelon, Captured in Still Lifes

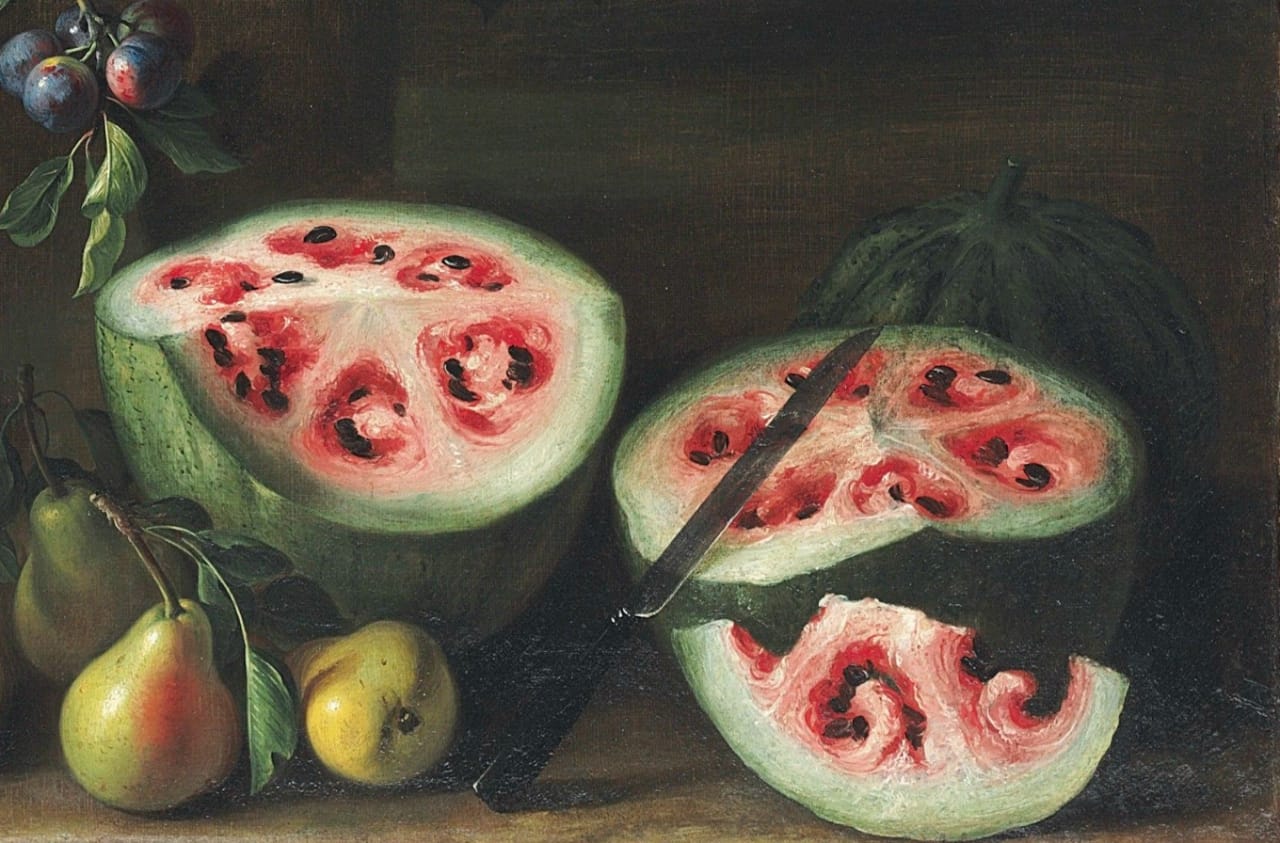

The watermelons of our summers are not the watermelons of yesteryear, as demonstrated by a 17th-century painting by Italian artist Giovanni Stanchi.

The watermelons of our summers are not the watermelons of yesteryear, as demonstrated by a 17th-century painting by Italian artist Giovanni Stanchi. The Renaissance still life depicts a sliced watermelon with a knife resting over pinkish, pale flesh full of dark seeds— much different from the lush reds with only a scattering of seeds that we see when slicing them open today.

As Vox reported this week, the painting captures an early form of the fruit so well that James Nienhuis, a University of Wisconsin horticulture professor, shows it to his classes when teaching crop breeding. The painting, which was auctioned last year at Christie’s, captures the watermelon in the midst of domestication from its wild form, which originated in Africa.

Over time, watermelons were bred to have different shapes, fewer seeds, more water and sugar, and that rich, red flesh. And they’re still evolving: we now have seedless watermelons, square watermelons, and even — horror — watermelons with human faces. Most of us likely realize on some level that the majority of the fruits, vegetables, and meat in our grocery stores are not completely natural, resulting from centuries of selective breeding and modifications. For example, almost all of our carrots are orange despite the fact that they grow in shades from yellow to purple, the result of a 17th-century cultivating frenzy of an orange breed with a hefty amount of beta-Carotene, as a tribute to William of Orange. The peach, also, once only found in China, was cultivated to be bigger, sweeter, and have a smaller pit for easier consumption.

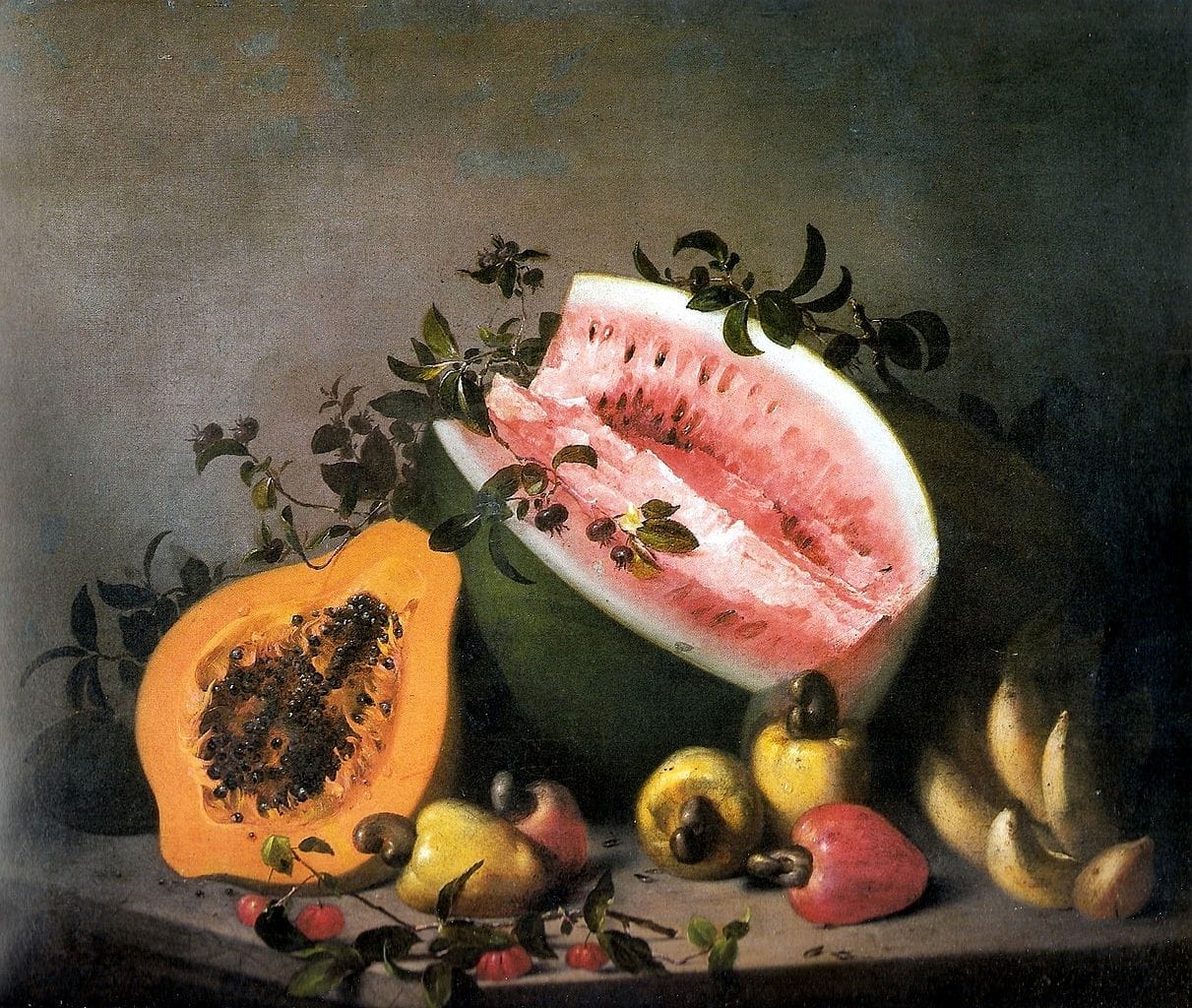

Old master still-life artists like Stanchi froze fragments of time, including moments in our agricultural history. Below are more examples of watermelons of the past captured in art.