The Humble Art of Decorated Paper

In April of 1789, a few months before the storming of the Bastille, the paper factory of Jean-Baptiste Réveillon in Paris was taken over by labor protestors, who commandeered the machines to print paper in red, white, and blue.

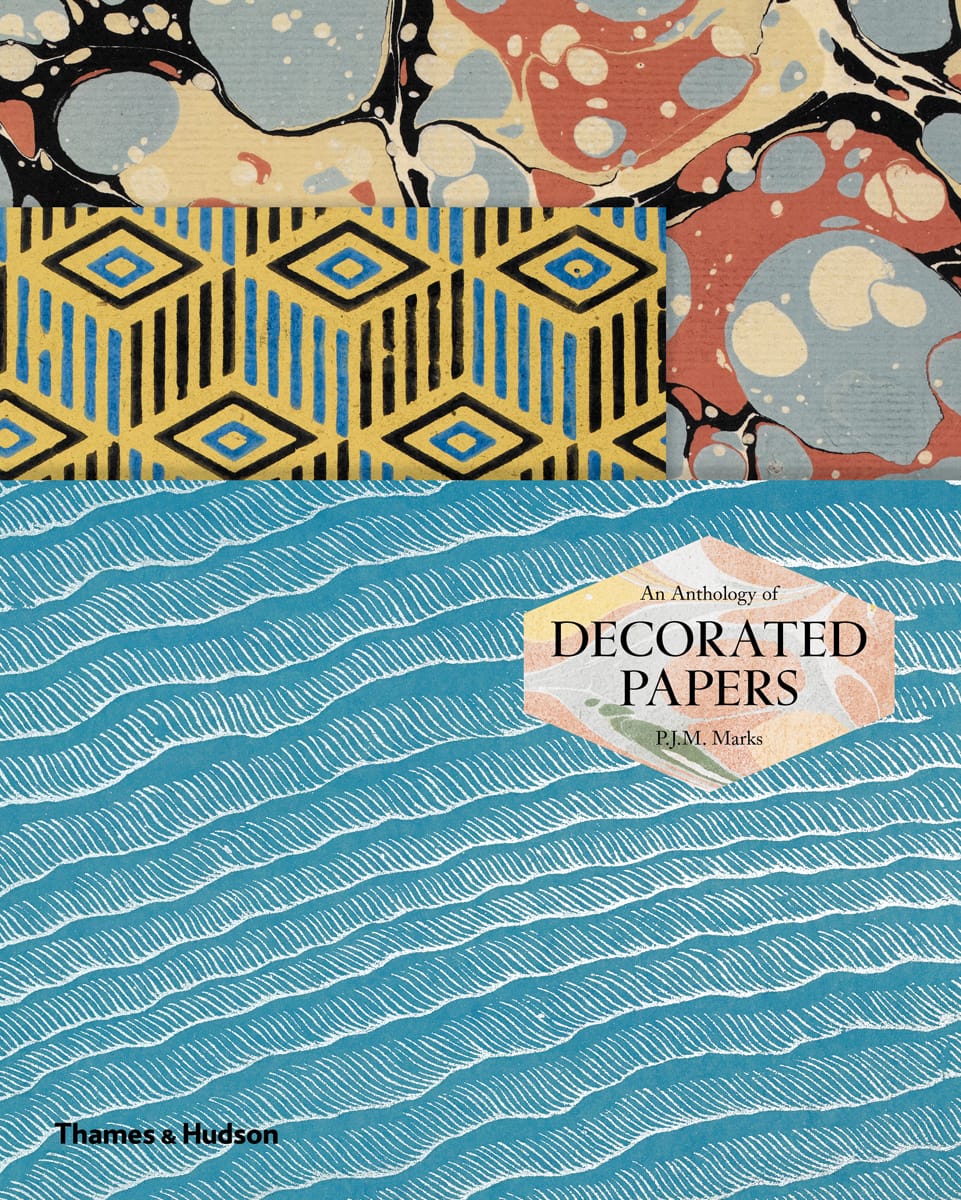

In April of 1789, a few months before the storming of the Bastille, the paper factory of Jean-Baptiste Réveillon in Paris was taken over by labor protestors, who commandeered the machines to print paper in red, white, and blue. This early act of the French Revolution is just one of the intriguing historic moments in An Anthology of Decorated Papers by P. J. M. Marks, out this month from Thames & Hudson.

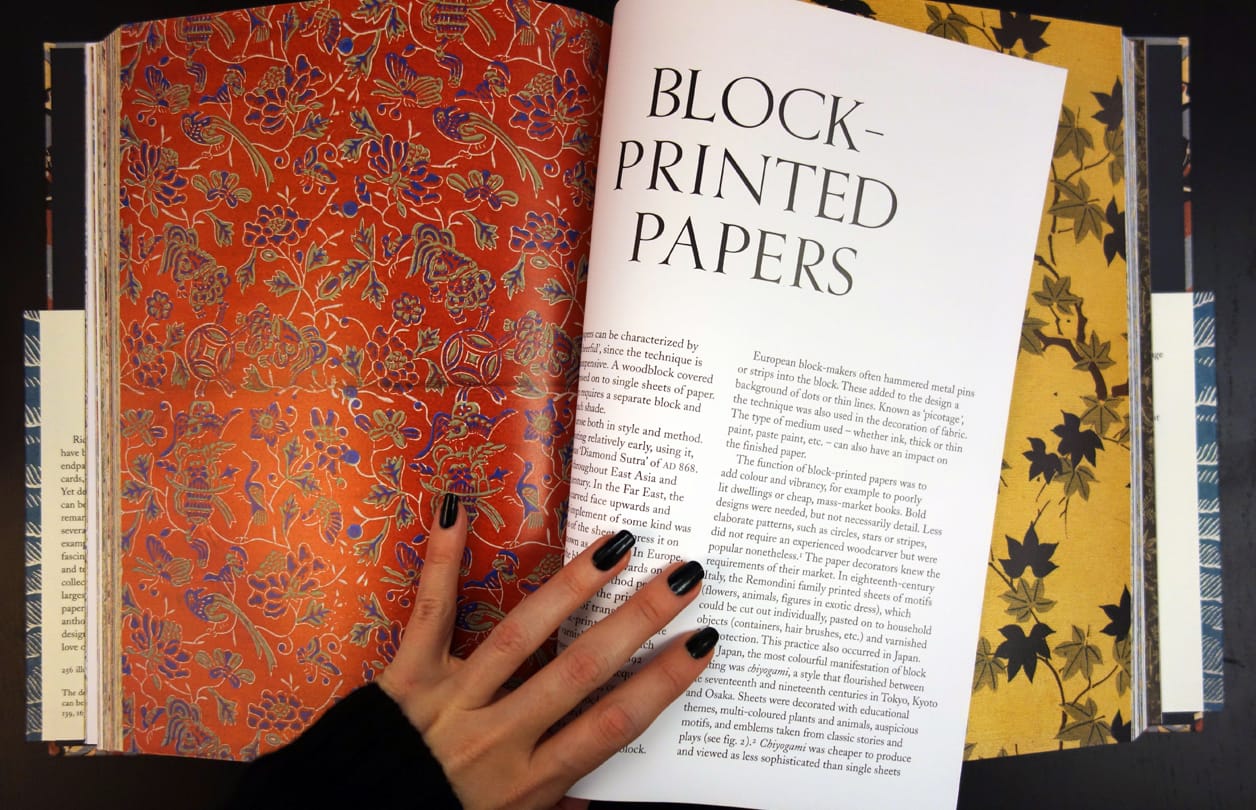

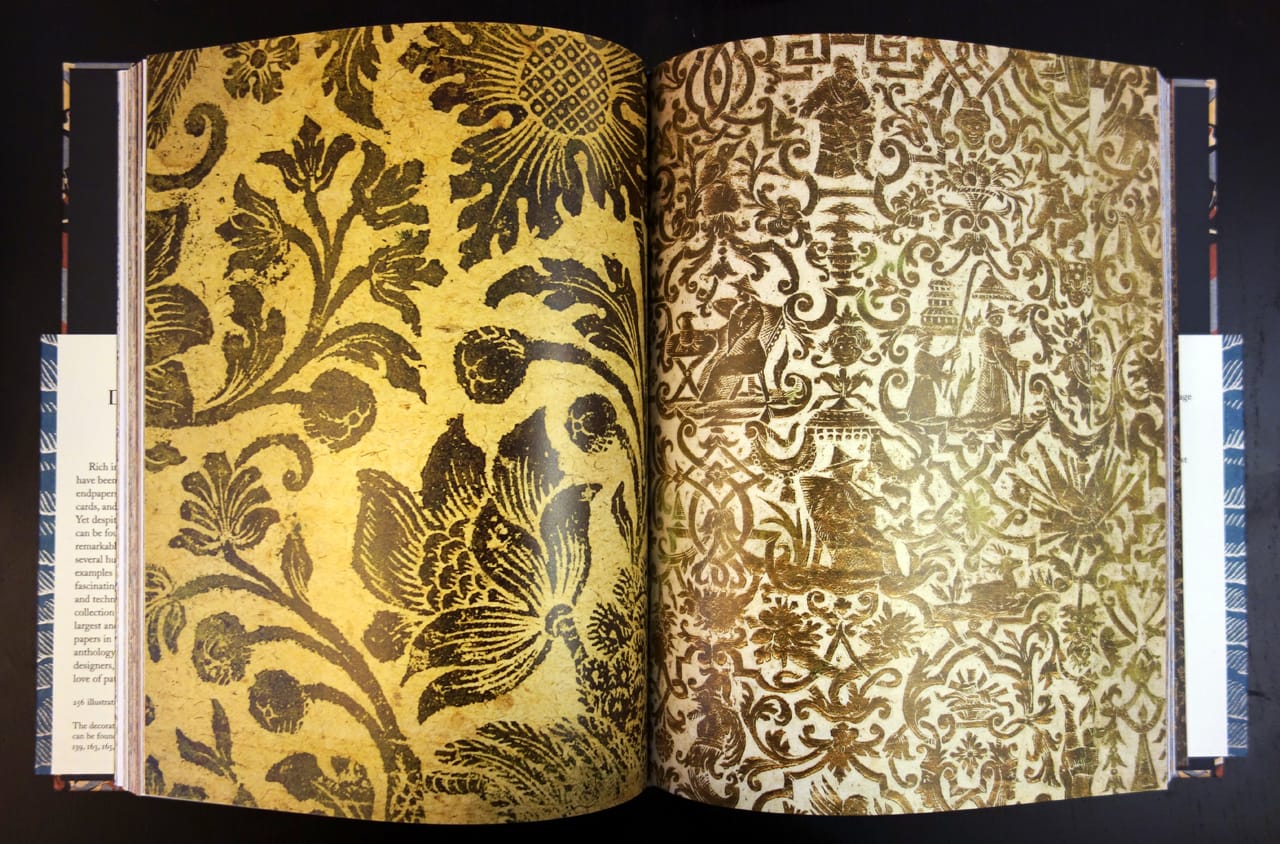

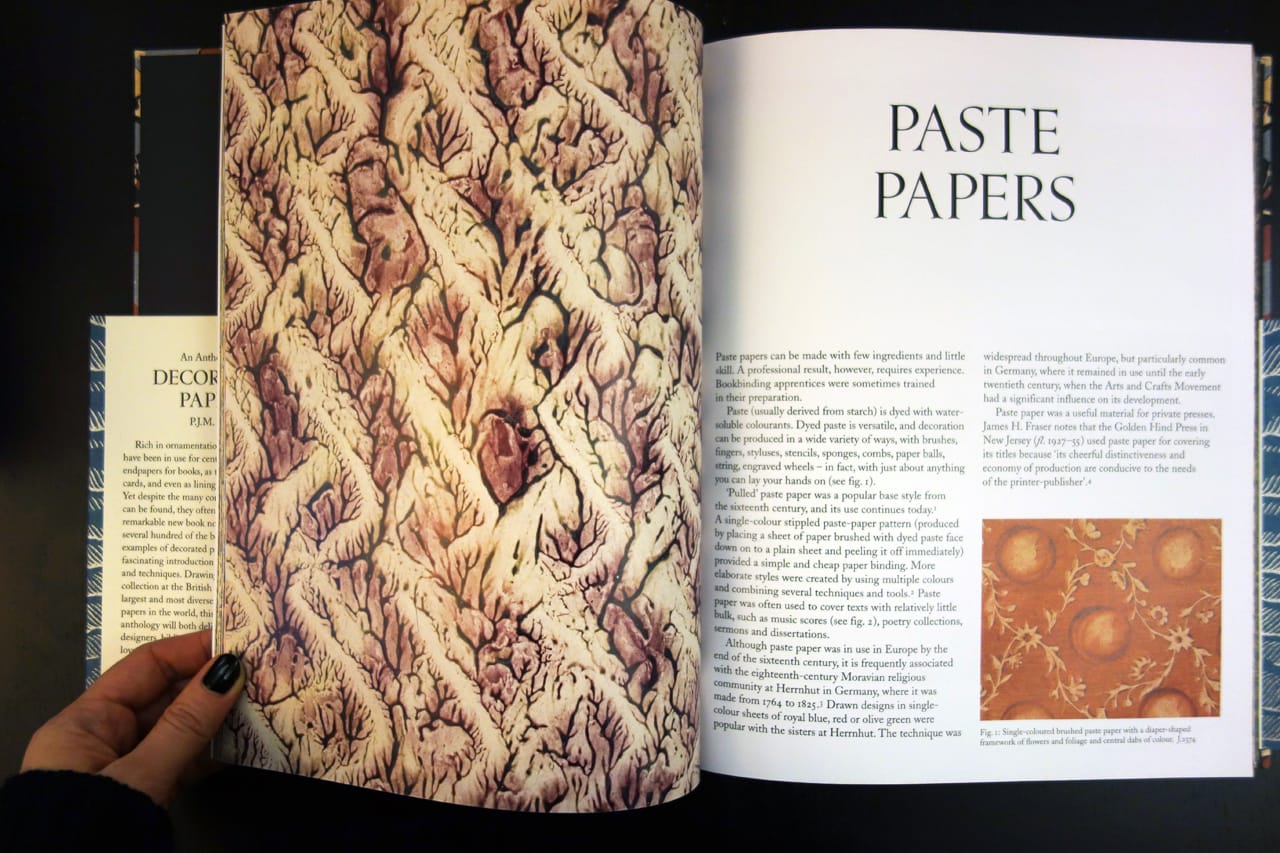

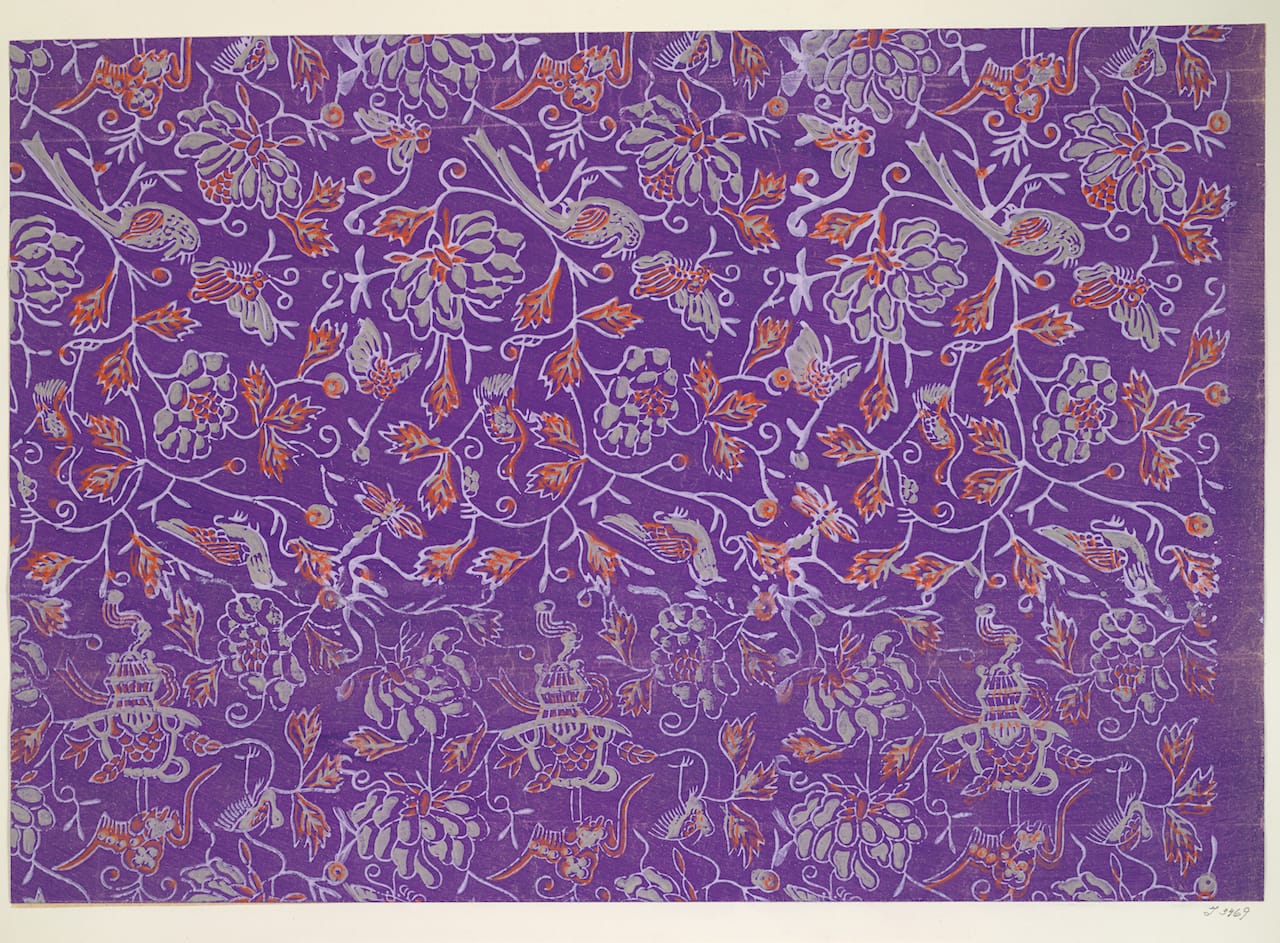

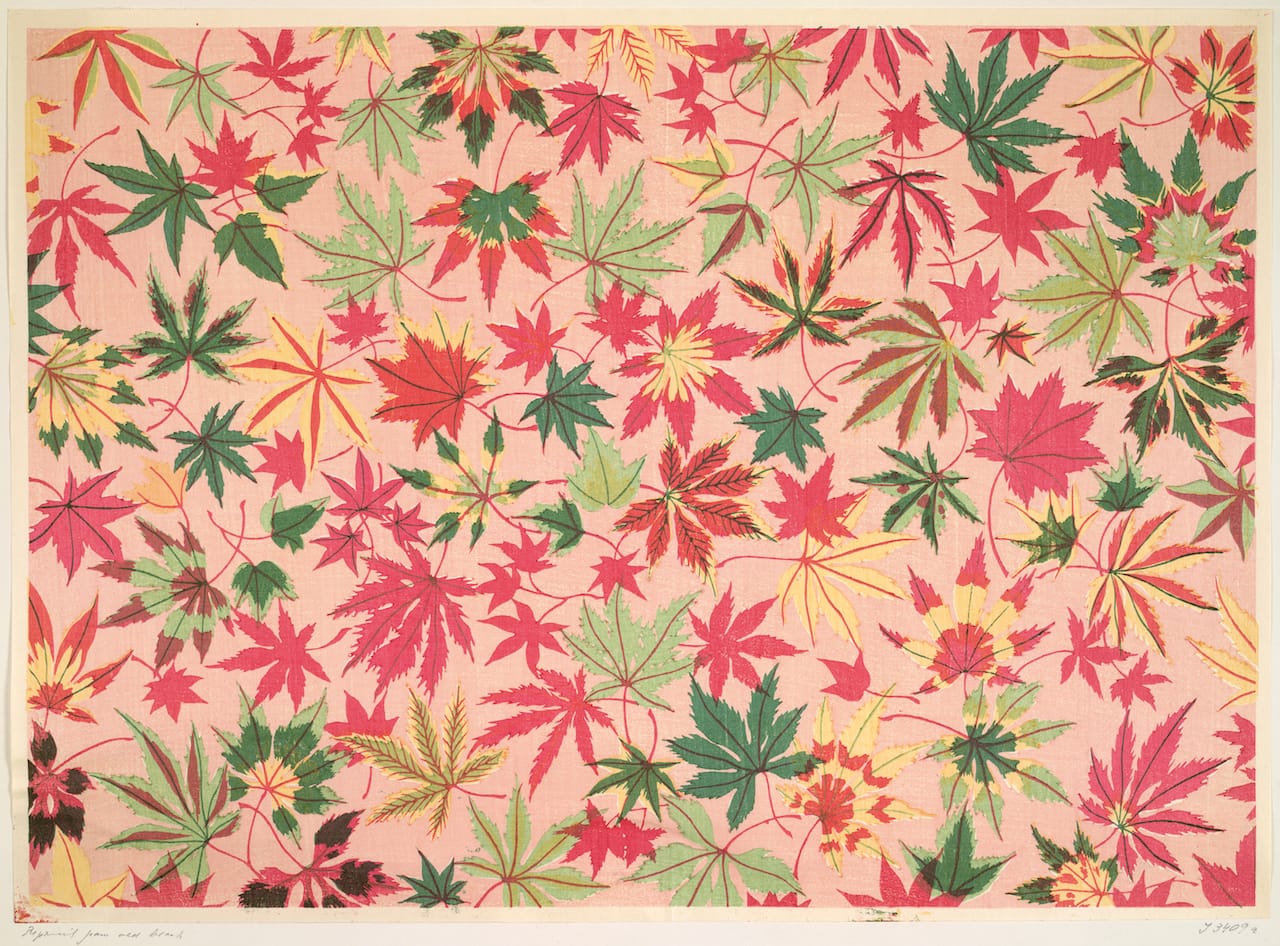

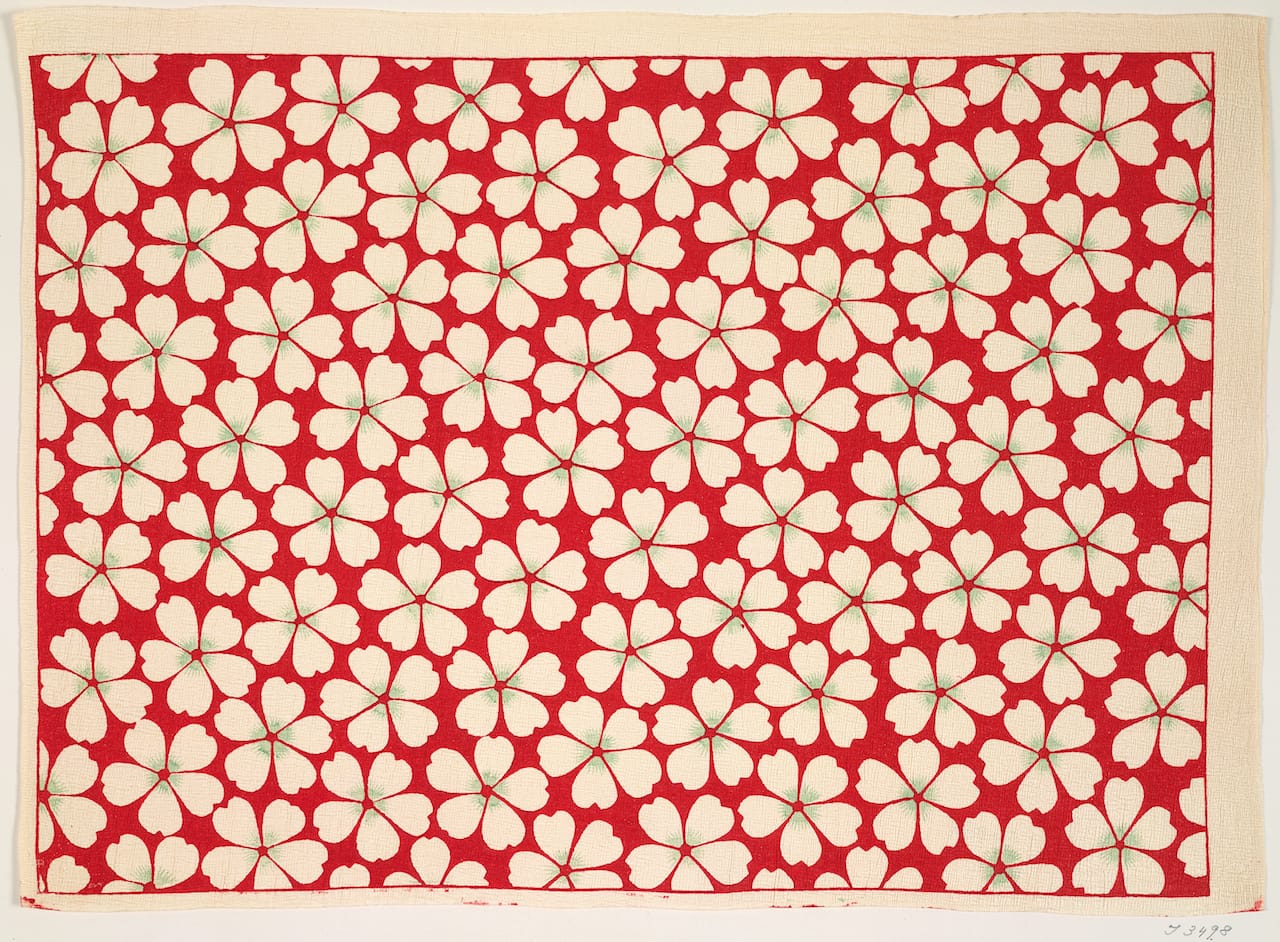

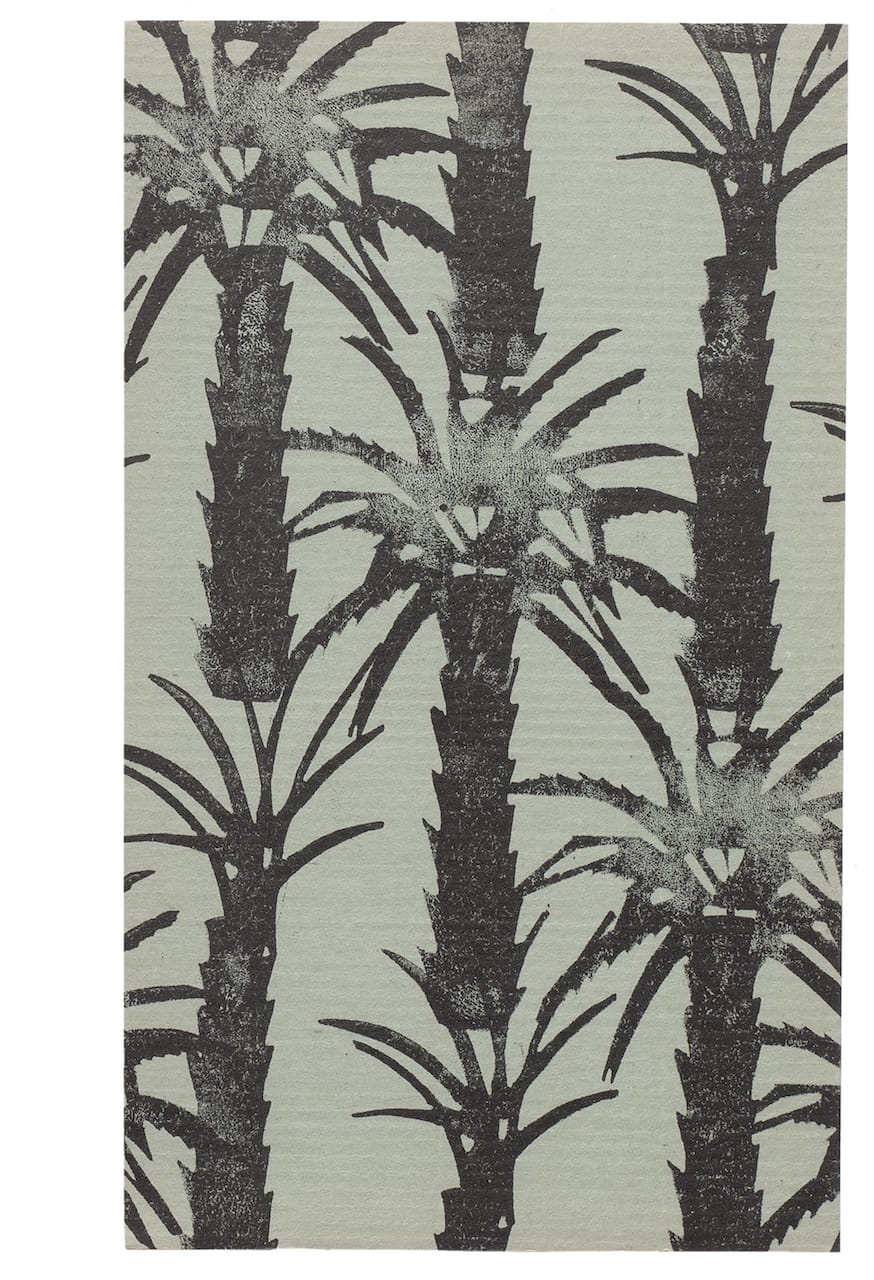

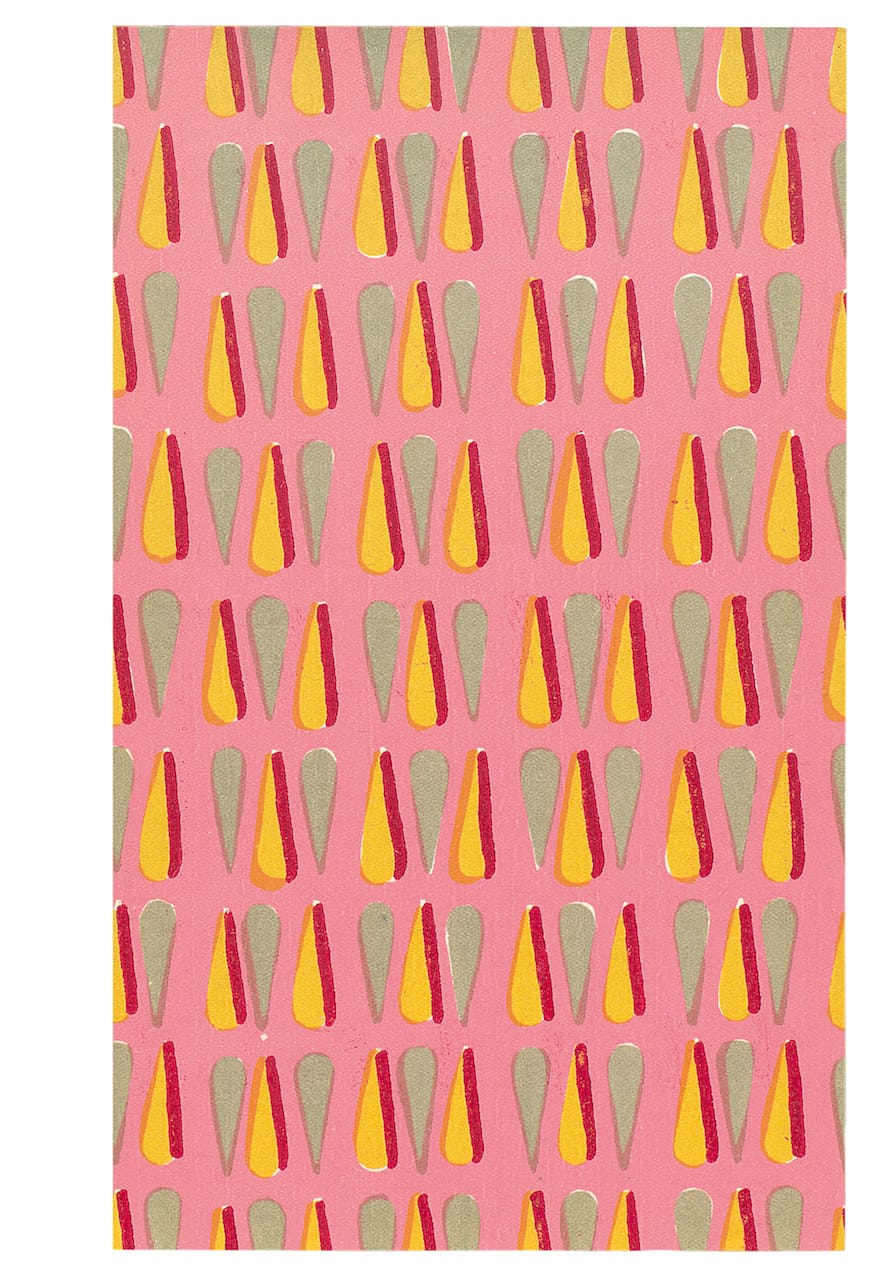

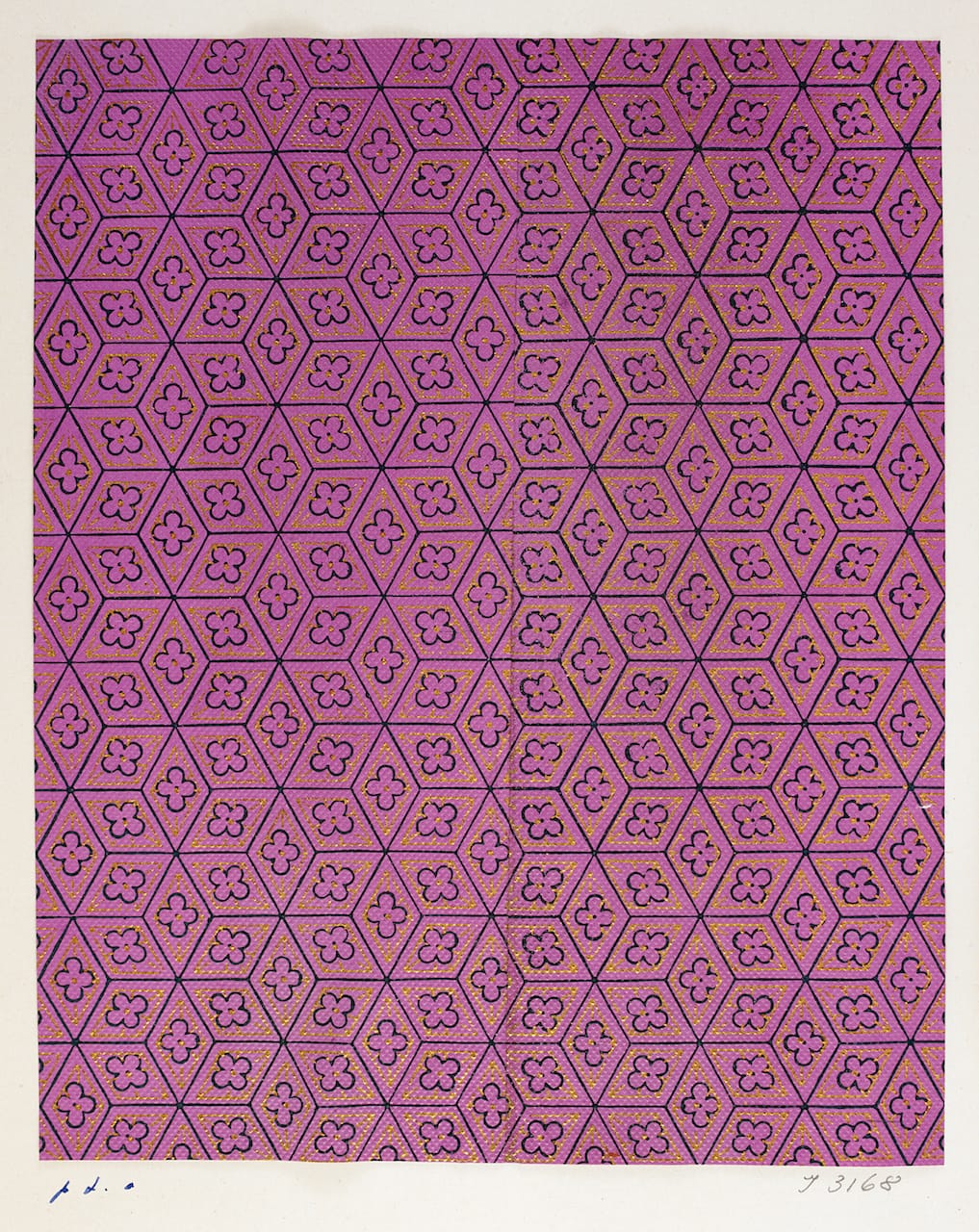

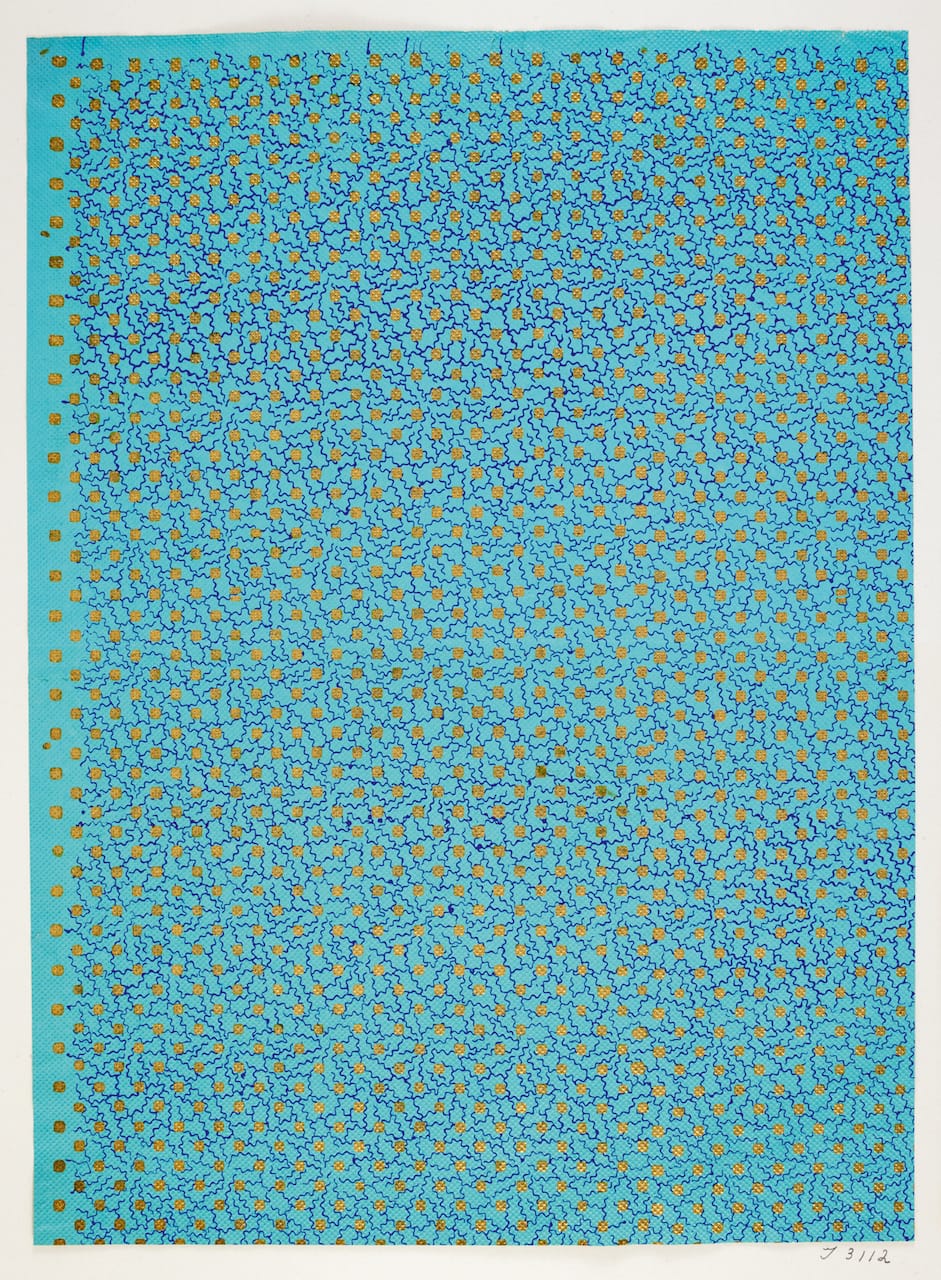

A book about decorated papers doesn’t seem like it would be that compelling, but Marks, curator of bookbindings at the British Library, examines the evolution of the humble art form in the context of its time and place. The over 250 examples in the book are from the British Library’s Olga Hirsch Collection of Decorated Papers. Hirsch, who died in 1968, was a bookbinder, and much of the collection of over 3,500 papers focuses on book endpapers and other publishing ephemera. There are also wrappers, backs of playing cards, currency paper, wallpaper, musical instrument covers, and other examples of the medium, mostly dating from the 16th to 20th century.

Decorated papers as an art form haven’t been thoroughly researched, and being that they were often mass-produced, haven’t been traditionally of high value. Marks writes:

Decorated papers offer much more than a mere backdrop to the era in which they were created. There is still scope for discovery. Why did the English enthusiastically adopt marbled papers when the Scots preferred gold? Why, for that matter, did European marbling develop in such a different way from the Turkish style on which it was based? Fashion, access to materials (the astragalus plant, whose resin makes the water more viscous in Turkish marbling, is absent in Europe) and different cultural imperatives must be considered.

Brocade foil papers could decorate religious books in Europe, while in China a version known as “tea chest” paper replaced the toxic lead lining that had previously been used in packaging tea. Paper could also reflect cultural value and exchange, whether paper with swallow birds in Japan installed in homes for luck, or an 18th-century German paper showing an early interpretation of a crocodile, which appears a bit like a distorted bird, with two talons on each foot.

Importantly, decorated papers have long been accessible, whether handmade marbling, block printing, lithography, embossing, or mass-produced decoration of the 20th century. As Marks writes: “Unlike expensive oil paintings, decorated papers were available to all but the poorest in society,” and thus reflect the popular tastes of each age.

An Anthology of Decorated Papers by P. J. M. Marks is out now from Thames & Hudson.