The Indian Observatories That Inspired Noguchi's Sculptures

Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi’s highly formal approach to design borrows cues from varied sources, including architecture, sculpture, and photography.

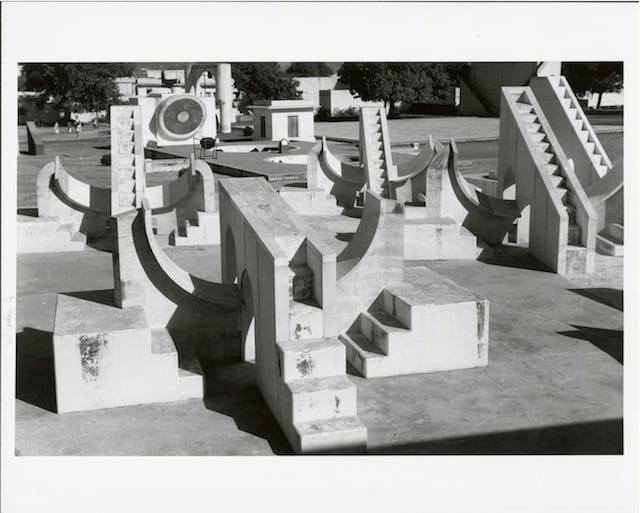

Japanese-American artist Isamu Noguchi’s highly formal approach to design borrows cues from varied sources, including architecture, sculpture, and photography. Noguchi as Photographer: The Jantar Mantars of Northern India at the Noguchi Museum in Long Island City displays Noguchi’s eye for structure, as observed through his camera lens. While not necessarily innovative from a compositional standpoint, his photographs of a series of observatories in the Jaipur state of northern India illustrate design concepts that informed the artist’s work, namely his ideas about the symbolic relationship between structure and space.

Noguchi often traveled with the intent of absorbing the local architecture style, recording his experience with his camera. His photographic perspective elucidates his fascination with the Jantar Mantar, the name for the observatories meaning “calculation instrument.” By observing light’s interplay with the geometry of these structures, Noguchi’s photography provides a schematic of the structural elements integral to these buildings.

Most outside photographers have treated Indian architecture as an organic outgrowth of “foreign” terrain. Noguchi, however, was able to see through the colonial shroud and appreciate the observatories’ design. The Jantar Mantars were commissioned by Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II in the 1720s to provide a tool for measuring celestial bodies on a scale more befitting than the small brass instruments typical of the day. Noguchi’s photographs capture the intentional design of these distinct buildings, and how they manifested humanity’s desire for understanding the world around it.

Noguchi’s architectural lexicon was expanded by the observatories’ geometric elements. In Jaipur, Noguchi discovered a spiritual predecessor to his own work, as the Jantar Mantars echoed Noguchi’s ideas regarding architecture’s eternal fundamentals. Although most of Noguchi’s works throughout his lifetime were not built for the purpose of astronomy, he employed similarly simplistic shapes to build relationships between observers and their surroundings, such as his Seattle installation Black Sun, through which you can see the Space Needle. He would go on to compose several structures employing these nodes of design.

His sculpture “The Angle” displays a basic interaction between light and shape, illuminating an underlying structure of nature. This piece is a minimalist composition, consisting of two segments, each of a different type of material, intersecting at a corner, causing a shadow to fall that shifts depending on the time of day. “The Angle” reflects Noguchi’s love of simplicity.

![Isamu Noguchi's Model for "Playscapes" (1975 - 1976, Basswood, 10 1/2 x 47 x 34 1/2 in. [26.7 x 119.4 x 87.6 cm])](https://hyperallergic.com/content/images/hyperallergic-newspack-s3-amazonaws-com/uploads/2015/03/playscapes.jpg)

The simple shapes Noguchi observed in his photography became versatile components in projects throughout his career. He borrows many elements from the Jaipur observatories in his “Playscapes” playground in Atlanta. By stripping each borrowed element down to its most fundamental form and function, Noguchi avoids haphazard, meaningless pastiche. “Playscapes,” instead, uses these basic shapes to evoke the childlike, creative impulse of building a “beginning world, fresh and clear.”

Noguchi received the opportunity to build a structure with the same astronomical purpose as a Jantar Mantar in 1976. His “Sky Gate” piece was constructed in Hawaii specifically to observe the phenomenon known as “solar noon,” locally referred to as the “Lahaina moon.” While at first glance this piece bears little aesthetic resemblance to the Jaipur observatories, it embodies the spirit behind Noguchi’s photographs, as the “Sky Gate” is constructed to observe a specific type of astrological event.

While Noguchi’s interest in the Jantar Mantars stemmed from an aesthetic rather than spiritual appreciation, his employment of form, space, and light enables similar interactions between people and their surroundings. The enduring legacy of Noguchi’s work is a testament to the eternal functions of minimalist design.

Noguchi as Photographer: The Jantar Mantars of Northern India continues at the Noguchi Museum (9-01 33rd Road, Long Island City, Queens) through May 31.