The Madcap Masonry of Clinker Bricks

With twisted, charred shapes distended in chaotic lines, clinker brick looks like the deranged work of a madman.

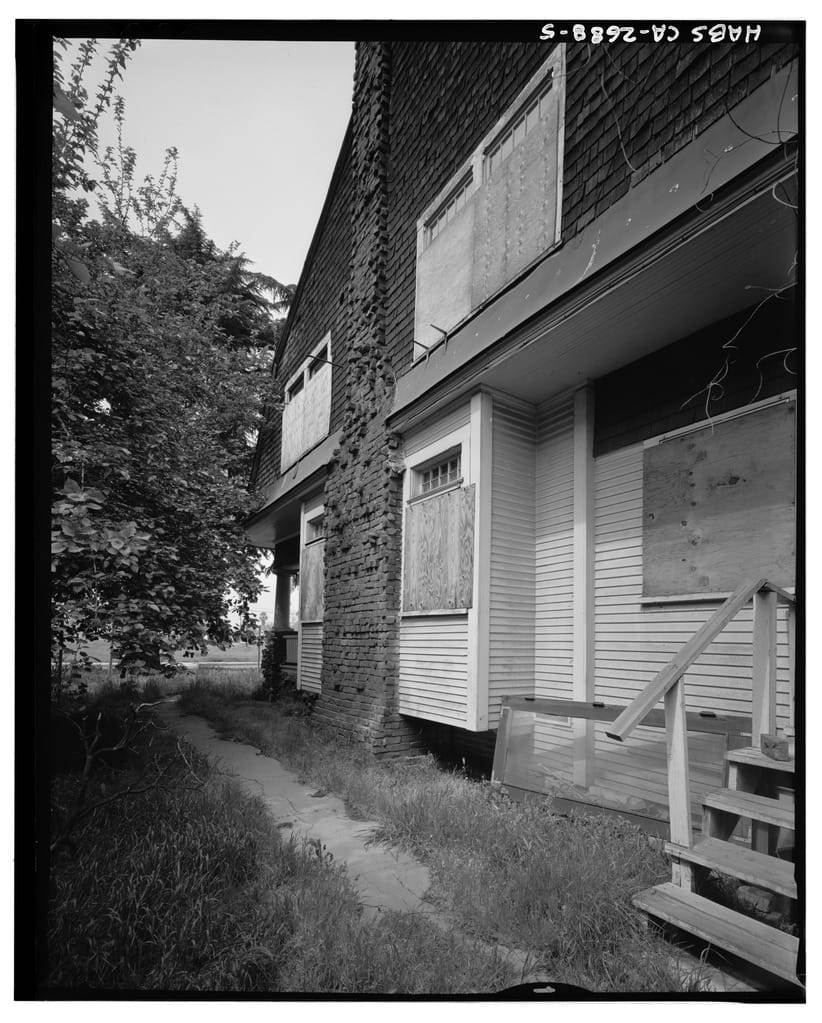

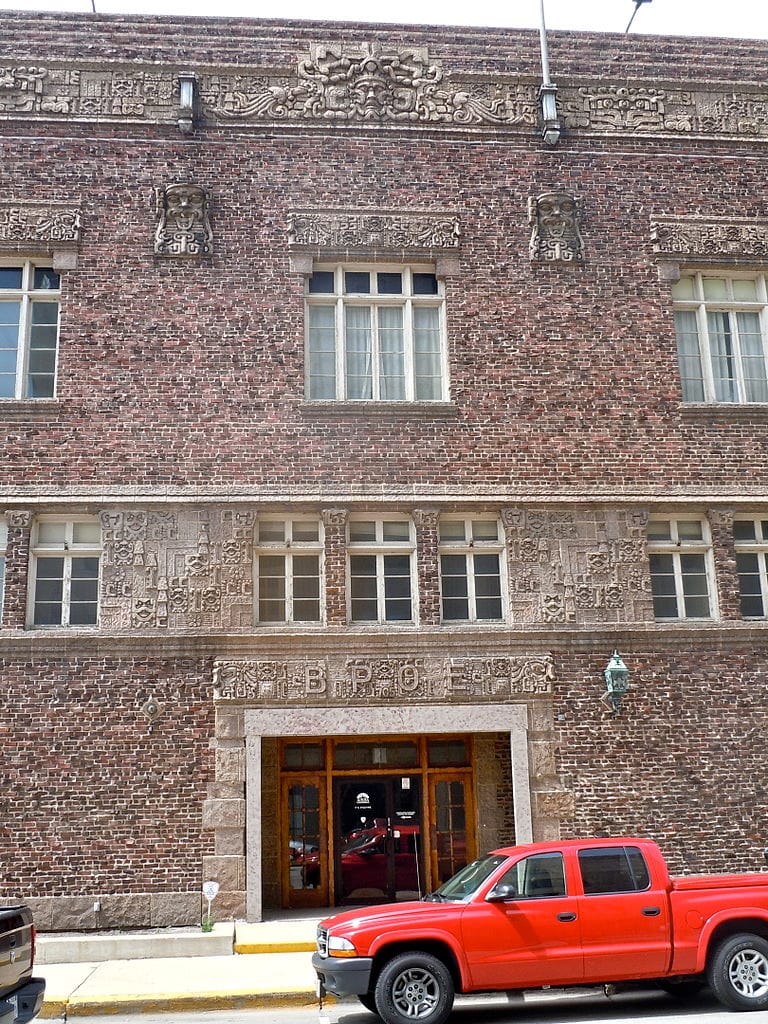

With twisted, charred shapes distended in chaotic lines, clinker brick looks like the deranged work of a madman. Around 1900, thanks to the Arts and Crafts movement, these previously discarded chunks of vitrified material from the brick-making process were suddenly prized for their organic feel. Built into walls, fireplaces, and foundations across the United States, a few examples still stand, appearing like moments of insanity in our mostly uniform architecture.

I first came across clinker brick at Memorial Park Cemetery in Oklahoma City, where a huge wall rambles around the burial ground with waves of blackened brick that seem salvaged from some Krakatoa-like disaster, assembled as if someone built it by touch instead of sight. At first I couldn’t understand how anyone once considered this beautiful, yet comparing it to the huge neighboring car lots with their identical, shiny trucks and sedans lined up alongside the smooth highways, there’s something bold about how it celebrates disorder.

The “clinker” name comes from the ringing sound made when these bricks got too close to the kiln flames and fused together. Their use by architects like Greene and Greene based in Pasadena, California, was partly a reaction to the perfectly manufactured bricks that were the new standard in the 20th century. It was also affordable when mixed in with standard bricks. Clinker wasn’t the only unusual brick design of the early 1900s — tapestry brick, for example, mixed various colors — although it was the most distinctive, transferring the Arts and Crafts interest in rustic traditions onto the industrial material.

Craftsman-era bungalows, where much of the clinker brick survives, are where it got the nickname “peanut-brittle-style masonry.” There’s also the Holy Trinity Anglican Church in Strathcona, Alberta, which influenced the city of Edmonton to construct around 150 buildings with clinker brick. And there are a few examples in New York City, such as Crystal Gardens apartments in Astoria, and apartment buildings at 419 East 57th Street and 405 East 54th Street in Manhattan by the New York Architectural Terra Cotta Company. Susan VanHecke wrote in the 2006 “The Accidental Charm of Clinker Bricks” for Old-House Journal: “In these days of automated manufacturing, when perfectly identical bricks are produced thousands at a time, clinkers are all but nonexistent.” Now abandoned kilns are often the source for clinker renovation or restoration.

The architect behind the Oklahoma City cemetery is anonymous, although it inspired a man named Oscar Allison in 1933 to build the clinker Capitol Hill Monument Co. in the city. Below are more photographs of the cemetery wall, as well as some clinker brick examples from around the United States.