The Problem with the "Medical Humanities"

A work of literature or art can be effective in different ways — most of which are by nature invisible.

The so-called “medical humanities” are on the rise of late. As literature and the arts find themselves at greater and greater pains to justify their work to the better-funded half of the academy, they appeal with increasing frequency to the medical utility of reading or making art: drawing on the vocabulary of psychology, medical humanists insist that literary fiction promotes empathy and that learning languages prevents Alzheimer’s. One of the latest in a long line of utilitarian defenses of the humanities is Belinda Jack’s excellent piece in the Times Higher Education, which argues that the medicinal effects of poetry have been understated. Poetry, Jack maintains, is an underappreciated remedy for depression.

At a time when the gap between the sciences and the humanities looms large, Jack’s call for interdisciplinary approaches to literature and medicine is admirable: “Psychology can certainly play a part in both biography and biographical readings of literary texts, for example. Pharmacology can enlighten us in relation to drug-induced creative states of mind,” she writes. But the crux of her essay represents one more unwelcome attempt to subject the arts to standards derived from the sciences.

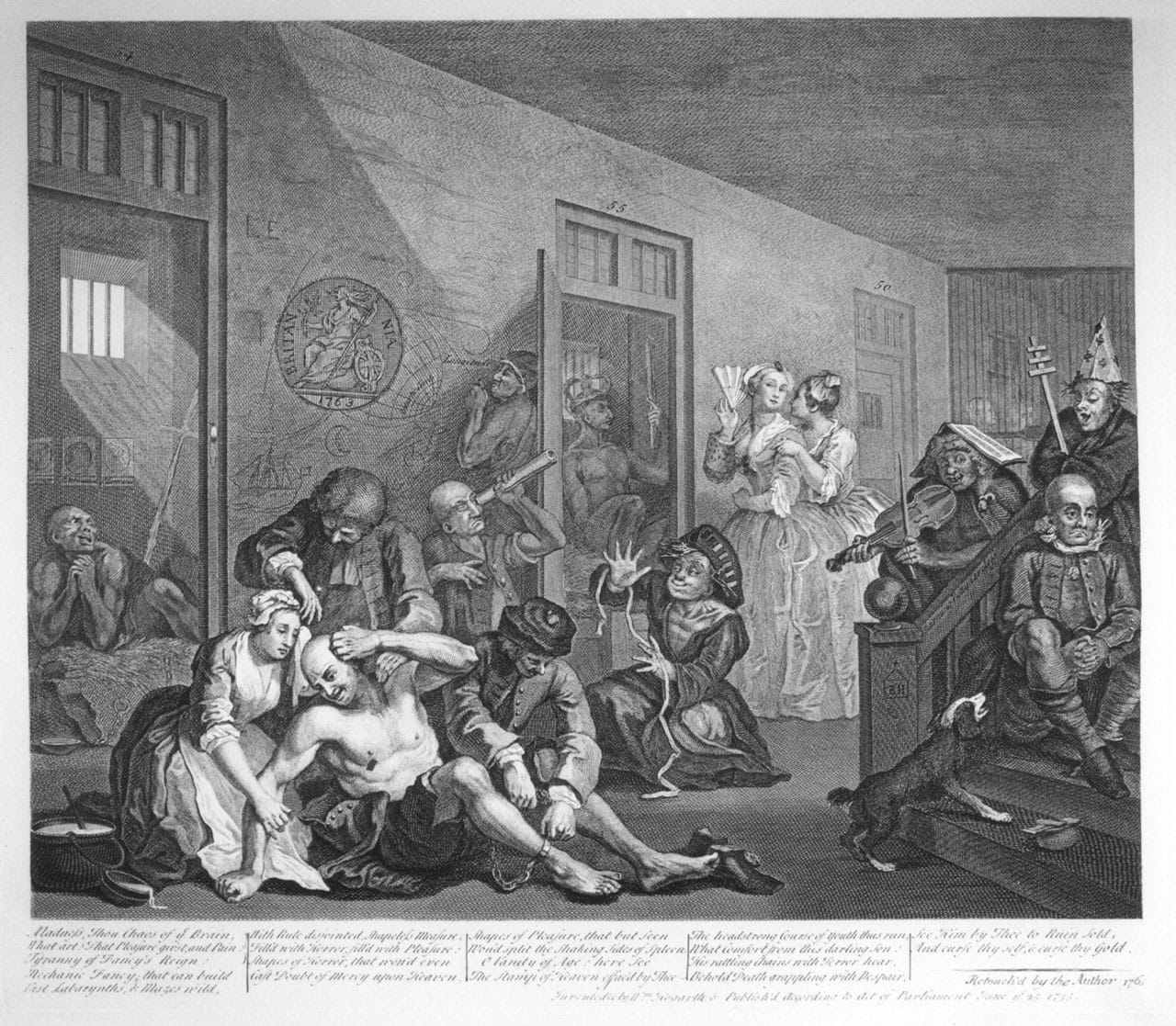

A medicine is “successful” when it produces a noticeable change in some sick party; by design, its efficacy is observable and, to some degree, measurable. In contrast, a work of literature or art can be effective in different ways — most of which are by nature invisible. A book that subtly alters our worldview, a painting that discomfits us, or a play that brings its audience to tears: these all fall under the “successful artwork” umbrella. Sometimes, an artwork’s success is a matter of pure aesthetics, which don’t lend themselves to quantification. Poetry isn’t valuable because it’s comforting, as Jack suggests; much of the best poetry is disturbing. (“Every angel is terrible,” Rainer Maria Rilke wrote in The Duino Elegies.)

What’s more, because the medical humanist’s strategy relies fundamentally on the notion that literature can be put to practical use, it leaves literature’s defenders vulnerable to criticism when dealing with less obviously therapeutic art. I’m not sure Kafka ever cured anyone’s depression, but his writing has certainly raised important questions — and indeed, the questions are important in part because they’re so difficult, upsetting, and, yes, even depressing.

“Americans have always felt uncomfortable about any cultural activity that does not lead to concrete results,” Lee Siegel once wrote in The New Yorker. Anyone who wants to mount a more durable defense of the arts should appeal to their intrinsic, intangible value. If they occasionally help alleviate mental illnesses, that’s a bonus.