The Self-Invention of Helene Schjerfbeck

The Finnish artist’s first major exhibition in the US is a moving and harrowing document of her growth, as well as the psychic and physical ravages of aging.

Seeing Silence: The Paintings of Helene Schjerfbeck at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is a rare opportunity for Americans to encounter the stunning work of a mostly unknown artist — unknown, at least, here. Schjerfbeck is not some newly discovered or overlooked woman artist of the past. In fact, she has long been celebrated in Nordic countries, particularly Finland, where she is as culturally important as Edvard Munch is to Norway — that is, a defining voice of modernism.

One reason Schjerfbeck is so little known here is that the vast majority of her work is in Finnish and Swedish collections — though The Met acquired the single painting of hers in a major collection in this country, “The Lace Shawl” (1920), in 2023. Presumably, such an important exhibition and venue could do for Schjerfbeck what the 2018 Guggenheim show did for her fellow Swedish-speaker, Hilma af Klint: establish her as a globally recognized figure in 20th-century art. Schjerfbeck’s work is that exceptional.

As someone especially interested in Nordic women modernists, I arrived at The Met with high hopes for just such a splash — so I was bemused when I didn’t encounter a massive banner with her name out front on Fifth Avenue. Fortunately, Schjerfbeck’s work speaks for itself, especially her many penetrating self-portraits.

Born in Helsinki in 1862, when Finland was part of the Russian empire, Schjerfbeck grew up in a Swedish-speaking family — not unusual, as Sweden ruled Finland for hundreds of years before ceding it to Russia in 1809. Practically, this meant she could converse with the many Swedish, Norwegian, and Danish artists (Finnish is part of a different language family) active in Paris when she arrived in 1880 at the age of 18.

While Schjerfbeck had been a child prodigy — she enrolled at the Drawing School of the Finnish Art Society at age 11 — the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris did not yet admit women, so she studied at the private Académie Colarossi, where many other Nordic women artists also worked. A wall label for her “Portrait of Helena Westermarck” (1884), depicting her lifelong friend and fellow artist concentrating on her work, quotes Schjerfbeck writing years later about their time together in Paris. “My thoughts drift to that winter morning when we went to Colarossi — such happiness!" she writes. "There was no fixed agenda, we simply wanted to paint well during our studies — I had no grand plans for the future. I simply wanted to paint.” She would keep painting until the end of her life, a trajectory Seeing Silence traces via her many self-portraits.

The show opens with the fresh and assured “Self-Portrait” (1884–85), done while Schjerfbeck was studying in Paris. It is only the first of 40 self-portraits she made from her early 20s until the end of her life at age 83 — moving and sometimes harrowing documents of the growth of an artist, as well as the psychic and physical ravages of aging.

Not far from the opening portrait is probably Schjerfbeck’s most beloved work in Finland, “The Convalescent” (1888). Large for a painting of such an ostensibly unheroic subject, it depicts a disheveled child managing the boredom of illness in an age before TV and iPads, beside a small potted plant. Schjerfbeck knew such infirmity well, as she had permanently injured her left hip at the age of four, and was given art supplies by her amateur-artist father during her own childhood convalescence to occupy her. So this might be considered a kind of history painting describing the birth of an artist — a gentle counterpoint to her more traditionally heroic and nationalist scene from Finnish history, “The Death of Wilhelm von Schwerin” (1862–46) on the facing wall, depicting the death of a young count in the Finnish War against Russia.

Schjerfbeck returned to Finland in 1890, where she taught at the Drawing School in Helsinki, before moving to small-town Hyvinkää to care for her mother in 1902. There, she found her own route away from the naturalism she learned in Paris into a personal style of simplified, abstracted form and symbolic color. Wall texts describe the influence of French artists like Édouard Manet, Paul Cézanne, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and older examples ranging from El Greco to Renaissance frescoes. Yet there’s no mention of her Nordic contemporaries whose work often comes equally to mind, such as Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi and Norwegians Harriet Backer and Munch.

The resonance between her work and that of Munch is sometimes startling. Schjerfbeck’s poignant “The Tapestry” (1914–16), depicting a man in a dark suit and a blonde woman in white standing in an interior space that somehow also evokes a view of the sea, calls to mind Munch’s “Two Human Beings. The Lonely Ones,” especially the lost 1892 version (he made many). And while Schjerfbeck’s “Fragment” (1904) — an ethereal red-headed girl in profile, the canvas scraped and abraded — is described in the wall texts as having been influenced by Renaissance frescoes, it also reminds me of Munch’s “The Sick Child” (1885–86), with a similarly rough and reworked surface.

Whether or not Munch influenced Schjerfbeck, they shared a painterly dedication to the excavation of the self. The exhibition’s final gallery, with a dozen self-portraits that grow increasingly haunting as she ages, is a moving and dramatic closer. While early self-portraits rely on the naturalism she found in Paris and the serenity of Renaissance art in Italy, by the time she’s 50, as in “Self-Portrait” (1912), Schjerfbeck trusts her own instincts above anything else. Here, her asymmetric eyes — one dark-blue iris and one shining baby blue — imbue her with a witchy, Bowie-esque sense of self-invention.

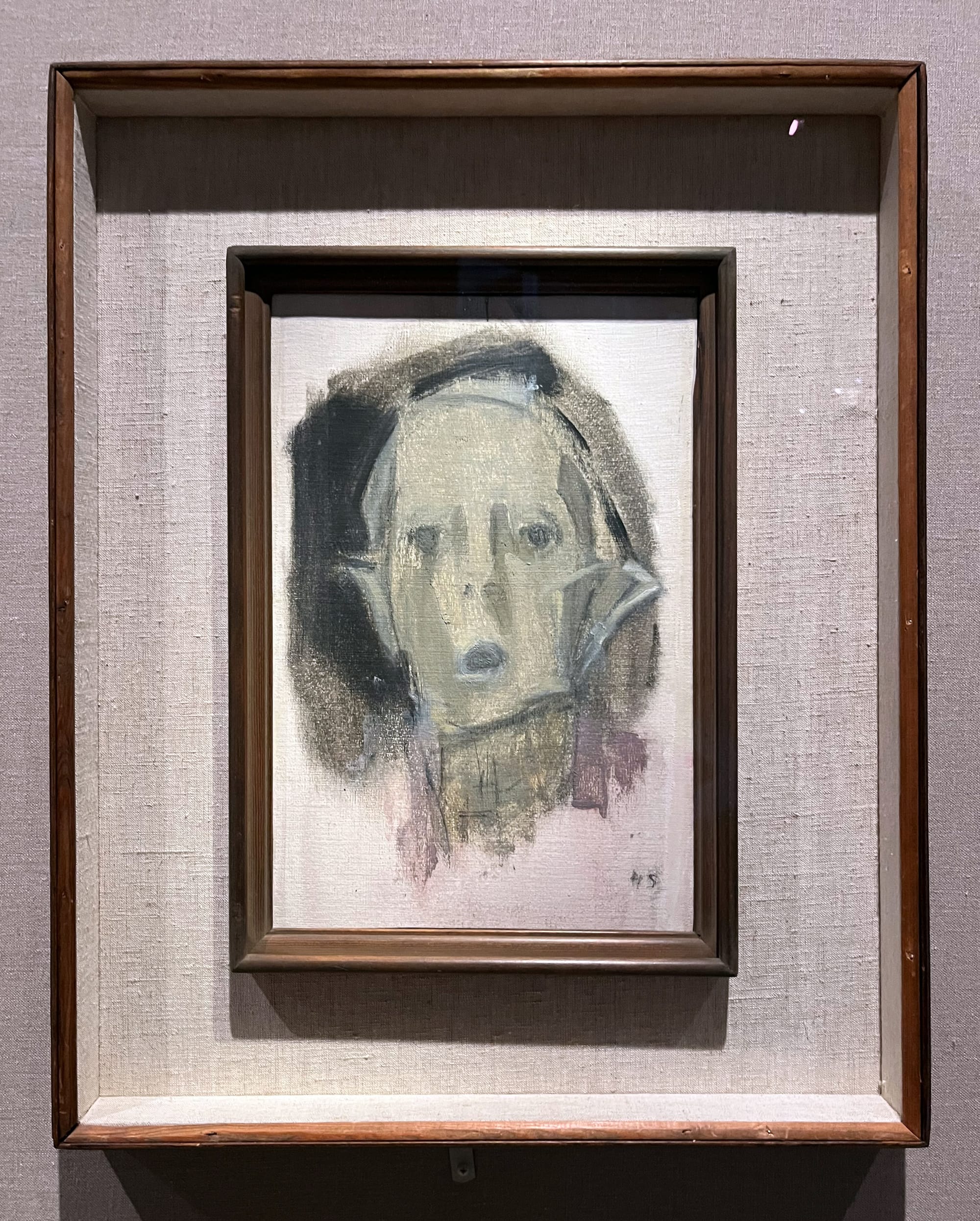

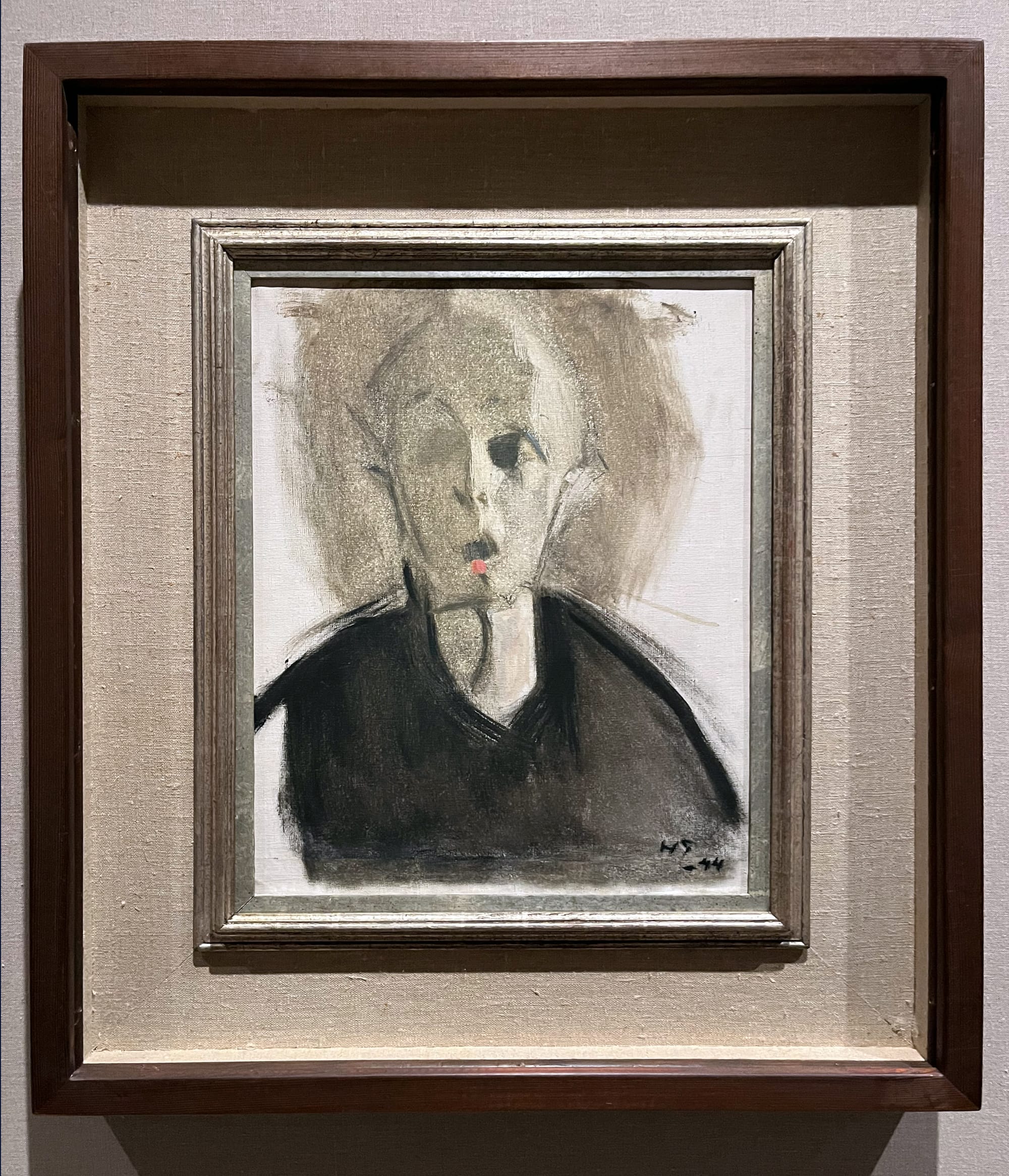

Maybe the most powerful thing about these late self-portraits is Schjerfbeck’s unflinching embrace of her monstrous, aging intensity. In “Self-Portrait with Red Spot” (1944) and “Self-Portrait in Black and Pink” (1945), with heads right out of a horror movie — the original Nosferatu (1922) comes to mind — the artist coolly appraises death. She seems more fascinated than afraid. As she wrote in 1937 to a former love interest, “No one has had so much fun as I have — or so much sorrow — but there’s been more joy.”

Left: Helene Schjerfbeck, "Self-Portrait in Black and Pink" (1946), oil on canvas; right: Helene Schjerfbeck, "Self-Portrait with Red Spot" (1944), oil on canvas

Seeing Silence: The Paintings of Helene Schjerfbeck continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through April 5. The exhibition was organized in collaboration with the Finnish National Gallery / Ateneum Art Museum, and curated by Dita Amory and Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff.