The Soundscape of Genocide in Gaza

The broadcast of Netanyahu’s speech was not the first time Israel intentionally used sound and speaker systems to intimidate and terrorize the people of Palestine.

Over the past two years, the people of Gaza have been exposed to the sounds of bombs, drones, explosions, destruction, and sirens. These human-made sounds of terror have stood at the center of at least two of the United Nation Children's Fund’s campaigns and are abundant in testimonies made by Palestinians. Our feeds have been filled with documentation of men, women, elders, and children crying, shouting, and wailing. Some cry out for the loss of their loved ones, roaming helplessly within the rubble, in the ruins that were once streets and in the dilapidated hospital corridors. Mohamed Abo Dakka cried for the world to hear as he recounted the loss of eight members of his family in an Israeli airstrike in October 2023. Other haunting shouts and cries belong to those trapped under the rubble, documented by rescue teams and civilians, as well as family members. A video from November 2023 depicts teams trying to rescue a girl from under the rubble of a home. She pleads, “Get me out of here, please get me out of here … I can’t move … why is all this happening to us?” (emphasis mine). Her cry is also a collective one. Its magnitude resonates with the terrifying recent figure of 2,700 families that have been completely wiped out since October 2023.

How can we attend to the soundscape of a genocide with a critical ear, but also with the care and urgency it deserves?

On Friday morning, September 26, several Israel Defense Forces (IDF) vehicles were heading towards the Gaza border; some had a circular, megaphone-like speaker system, while others formed a wall of black speakers stacked on top of each other in four columns of six. They broadcast Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s speech at the United Nations 80th General Assembly. IDF soldiers involved in what they dubbed “Shout/Scream Operation” also admitted that they placed additional speaker systems inside the besieged and bulldozed Gaza Strip.

This sonic and spatial manifestation, however, marked 10 days since Israel relaunched and intensified its ground offensive in Gaza. Palestinians felt the weight of Israel's presence in every aspect of life and space they inhabit and through multifaceted corporeal sensations — seeing destruction and death; feeling hunger, pain, and fear; forcibly hearing crying, shouting, and bombardment. By the time of Netanyahu’s speech, at least 20 Palestinian people had been killed in Israeli attacks that morning. The number would rise to 60 by the end of the day, and a 17-year-old boy would die from starvation at Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in central Gaza. The very same day, a Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) International coordinator declared, “We have been left with no choice but to stop our activities, as our clinics are encircled by Israeli forces.”

The broadcast of Netanyahu’s speech was not the first time Israel intentionally used sound and speaker systems to intimidate and terrorize Palestinians in and outside Gaza, and even the people of Lebanon. “The Scream,” known for its use of high-pitched and sharp sound waves that target the vestibular system, is designed to disrupt one’s sense of balance and induce nausea and vomiting. The Israeli military deployed it on Palestinians protesting at checkpoints in 2005 before commencing its use on Israeli anti-government protests. In Sonic Warfare: Sound, Affect, and the Ecology of Fear (2012), musicologist Steve Goodman examines the Israeli Air Force’s use of sonic booms as “sound bombs” over the Gaza Strip in 2005. Sonic boom, he explains, “is the high volume, deep-frequency effect of low flying jets traveling faster than the speed of sound.” He writes that in Gaza, victims “likened its effect to the wall of air pressure generated by a massive explosion. They reported broken windows, ear pain, nosebleeds, anxiety attacks, sleeplessness, hypertension, and being left ‘shaking inside.’”

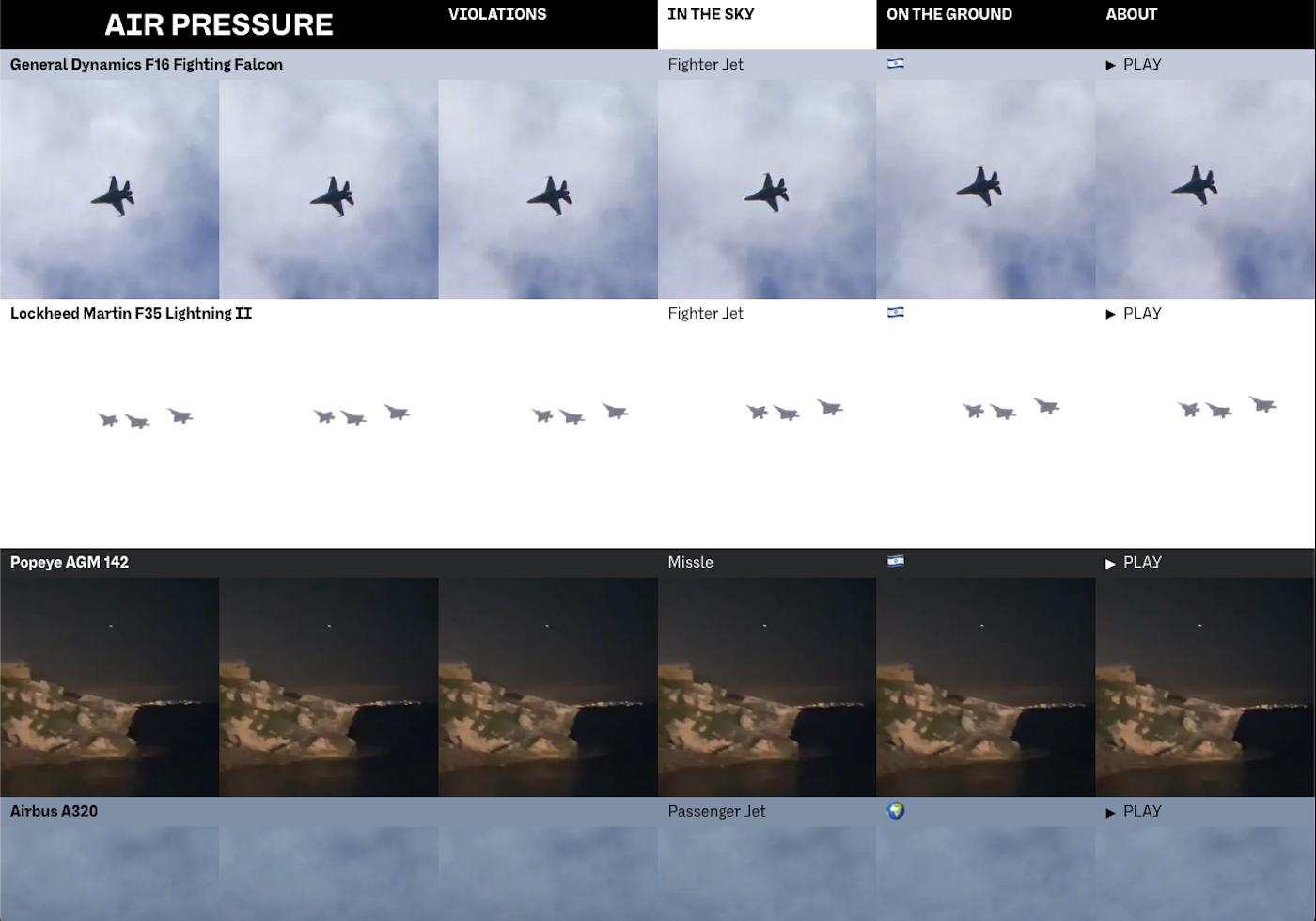

British-Jordanian artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan has been exploring the sonic landscape of Israeli aggression for several years. His interactive bilingual database, AirPressure.info, tracks and maps the ongoing illegal aerial invasion of Lebanon, whose airspace has been violated by around 22,335 Israeli military aircraft since 2007, according to the website. The database details the dates, the type of aircraft involved, the time of invasion, and its duration. It also includes field recordings of the different sounds each aircraft creates and footage of the attacks shared on social media by Lebanese civilians.

Israel’s military assault on Lebanon that began in 2023 killed more than 4,000 people, including the parents of artist Ali Cherri, and left over 16,000 wounded. Akram Zaatari, a Lebanese artist and founder of the Arab Image Foundation, grew up with the sight and sounds of bombings during the Lebanese Civil War from 1975 to 1990, often including it in his art and social media. His Instagram account often acts as a spatial, visual, and sonic memoir of his life in conflict-torn Beirut, including footage of this recent aerial aggression. These images were reminiscent of his childhood experiences, and his ongoing preoccupation with “capturing explosions” that he represents in artworks drawing on photographs he began taking at age 16, like “Saida June 6, 1982” (2006–9), depicting the first day of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. His critical short film “Letter to a Refusing Pilot” grapples with the soundscape of Israeli attacks and was presented at the Lebanese Pavilion at the 2013 Venice Biennale.

A recent account from Palestinian journalist Ahmed Dremly unpacks the sonic violence of Israeli explosive-laden robots, which have reportedly been used heavily in the last few months. “The sound of their explosion is, without doubt, the most terrifying noise in the world,” he told Middle East Eye’s Jerusalem Bureau Chief Lubna Masarwa.

“First, you feel it. A deep vibration. The air being sucked out around you,” he said. “Then the blast wave hits — often from behind — like a massive shove you never saw coming. Even two or three kilometres away, you’ll feel it in your bones. Something shifts, like the world’s about to crack open. And then the sound hits you. So loud it drowns out thought. So loud you want to scream, just to prove you still can.”

In his book Listening to War: Sound, Music, Trauma, and Survival in Wartime Iraq (2020), musicologist Martin Daugherty explains that keeping sanity in wartime requires people to wrench their attention away from the sounds of military assault and “toward more meaningful sounds, or sights, or smells, or bodily sensations — or the silent, internally voiced monologues that constitute thought.” These survival and coping mechanisms reverberate in Dremly’s account. “If I sense a blast is coming, I try to turn something loud on to disperse the sound,” he said. “I open my mouth to release the pressure. I try to brace myself, to imagine the blast before it happens, so it won’t come as such a shock.”

Fear instilled by sound is a recurring theme in recorded testimonies from the people of Gaza. The young journalist and poet Plestia Alaqad published her book The Eyes of Gaza: A Diary of Resilience earlier this year, detailing the first 45 days of the genocide and ending with her escape to Egypt. On day three, Alaqad’s neighborhood was bombed, and no evacuation orders were given beforehand. “I feel like we are all going to die. My neighbours are all running out of the building. Nobody knows where to go. It’s dark, and we can hear the bombing still going around us, like a sick musical soundtrack on repeat,” she writes. Afterward, Alaqad, her family, and her neighbors discovered that an apartment on the floor below them had been bombed.

Scholar Sara Ann Sewell’s research on the sonic experience of Holocaust survivors offers a framework to analyze these multiple layers of sound, as well as the triangular position of being auditors, subjects, and witnesses of the assault. Sewell emphasizes the overwhelming weight of sensory pressure brought down on each individual under attack, the experience of being both “assailed by the perpetrators’ brutal noises and fellow victims’ anguished outpouring.”

The soundscape of genocide, then, is cruel beyond measure. Being exposed to and entrapped in the sounds of your people’s suffering extends personal and collective trauma. Alaqad’s entries from days seven and 31 depict an overwhelming sonic cacophony, “an orchestra outside my window.” She notes the multifaceted, simultaneous soundscape of the genocide that includes natural sounds, industrial bombs and weaponry, and raw human cries that continue to haunt her. She writes:

Sitting in a corner of a hospital,

Trying to write a poem.

But a child is crying.

A cat is wandering.

A young girl is screaming.

Doctors are panicking.

And the sound of bombs?

Only getting closer.

These sounds of genocide also shape Alaqad and her fellow journalists’ spatial experience, such as scale, distance, and the temporal sense of safety. “As long as you can hear the sound of bombs, you’re safe,” she says. “Because you’ll never hear the rocket that kills you.”

Navigating the sonic landscape of violence, several musicians from Gaza have devised creative ways to use music as a tool of resistance and community-building. Ahmed “Muin” Abu Amsha is among them. The composer, musician, sound engineer, and educator, like many others, lost his home and recording studio and was displaced with his family several times. His description of the grating noise of drones resonates with the accounts of Alaqad and Dremly: “The most terrible thing in this war: the sound of the drones. It's with you all night and days, and it’s ‘zinging’ like your mind’s gonna blow.” In the face of this reality, Abu Amsha confronted the sounds of the drones by tuning his voice to them and singing over the noise in harmony. His recording of the song “Sheel Sheel Ya Ajmal Sheel,” sung with a group of children he started teaching in a displaced tent, went viral in September.

In an interview with Al Jazeera, Abu Amsha explained that finding music again has given him purpose and solace to endure the hardship, and created a needed change for the children. He founded Gaza Birds Singing to support children who were experiencing trauma and physical reactions, such as headaches, from the constant noise. “Concentrate on the tone of the drone, it’s going to be A or E,” he told them. Abu Hamsha’s and the children’s beautiful voices in harmony seem almost to tame or swallow the violent noise of the drone.

Nearly every morning, I open the Instagram page of 18-year-old Samih Madhoun to check that he is still alive, amid the ruins of Gaza City, playing his oud. Sometimes he’s alone, sometimes he’s with his brother. Recently, he played and sang with Abu Amsha. Both he and 25-year-old singer Hazem Alghosain describe how music became crucial to their survival, a mechanism to process grief and destruction, and even fulfill a purpose. “Music helps me endure suffering and emotional stress that we are living through in Gaza,” Madhoun told Msquared News in April. “I sing under the bombs, so that the world hears our voice … music is my life. The oud is part of who I am. I sing for my homeland, to express the loss of my country.”

In a personal essay published on Electronic Intifada, Alghosain writes that the genocide pushed him to bear witness and leave a trace behind “so that it can be said that in this land of forced starvation and annihilation, there was an artist who sang for hope. However, he may not have harbored it… I did not write this to lament. I write to etch my voice into an eternity in the face of oblivion.”

This genocide is also a cultural genocide, an ecocide, an urbicide, a scholasticide. These forms of colonial violence target institutions of knowledge production, the cultural and historical foundations of a people: museums and galleries, schools and universities, archives, historical sites, and libraries. Music-making, oral traditions, and cultural expression have always played crucial roles in resisting erasure. Palestinian artists and musicians show us time and time again that art, beyond offering hope and meaning, is a testimony, voiced in resistance to those who try to destroy a people and their stories.