The Whimsical Work of an Animal-Loving 19th-Century Printmaker

From portraits of his dog to Japanese motifs, these fine-lined images attest to the originality of Henri-Charles Guérard, who was one of the most respected printmakers of his time.

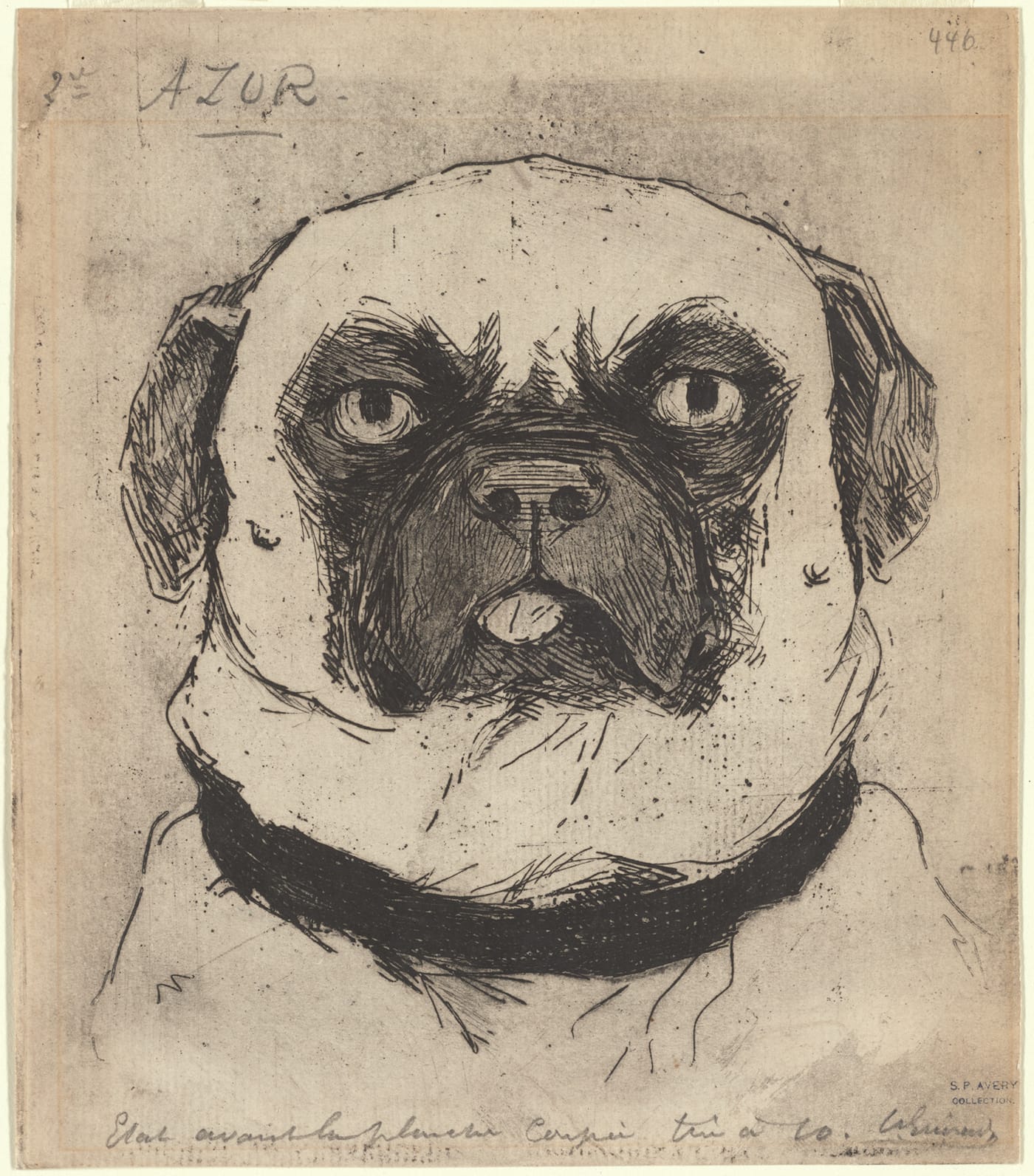

When he wasn’t sketching or bent over his etching press, hard at work, the 19th-century professional printmaker Henri-Charles Guérard often visited the Paris zoo. There, he observed elephants and monkeys, later preserving these creatures on paper in detailed prints. A lover of animals, the Frenchman himself owned a primate named Bi and a pug named Azor, both of whom he immortalized through illustration, too — particularly the canine, who often appears in Guérard’s works.

Four portraits of Azor are prominently shown at the exhibition currently at the New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, A Curious Hand: The Prints of Henri-Charles Guérard (1846–1897), curated by Madeleine Viljoen. Hung at the end of one of the library’s third-floor hallways, they imbue the pug with personality: he’s shown with his tongue out and eyes a little dazed; one portrait depicts him as a portly pup, sitting tall beneath his own name, etched in bold, Roman-style lettering.

While they are lighthearted, personal odes to his loyal pal, these fine-lined images attest to the skill and originality of Guérard, who was one of the most respected printmakers of his time. Manet often turned to Guérard to help him produce etchings of his own, a number of which are on view in the exhibition. Guérard, who in 1889 founded La Société des peintres-graveurs français with Norbert Goeneutte, was well-experienced in translating paint into prints: He made spectacular reproductions of famous paintings by the likes of Botticelli, Corot, Rembrandt, and Whistler. The library, which owns the largest collection of Guérard’s work in the country, has displayed a number of these; while they are faithful copies, they also attest to his painstaking handiwork and mastery of the line. Three print versions of “Whistler’s Mother” from 1883 also provide insight into Guérard’s process, capturing his work in different stages to show how he built up his lines to create subtle shadows and textures on paper that mimic the dark tones of Whistler’s paint.

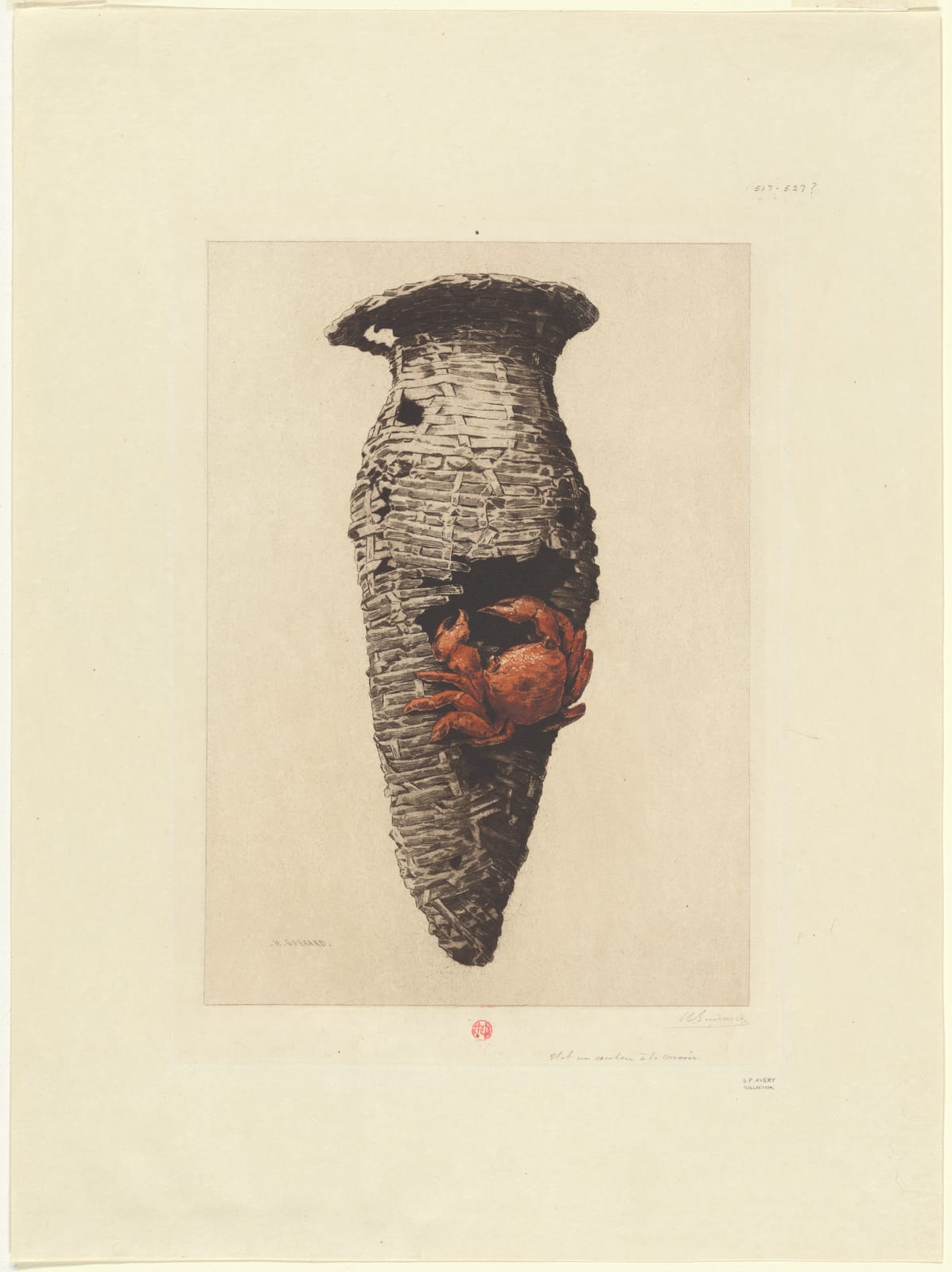

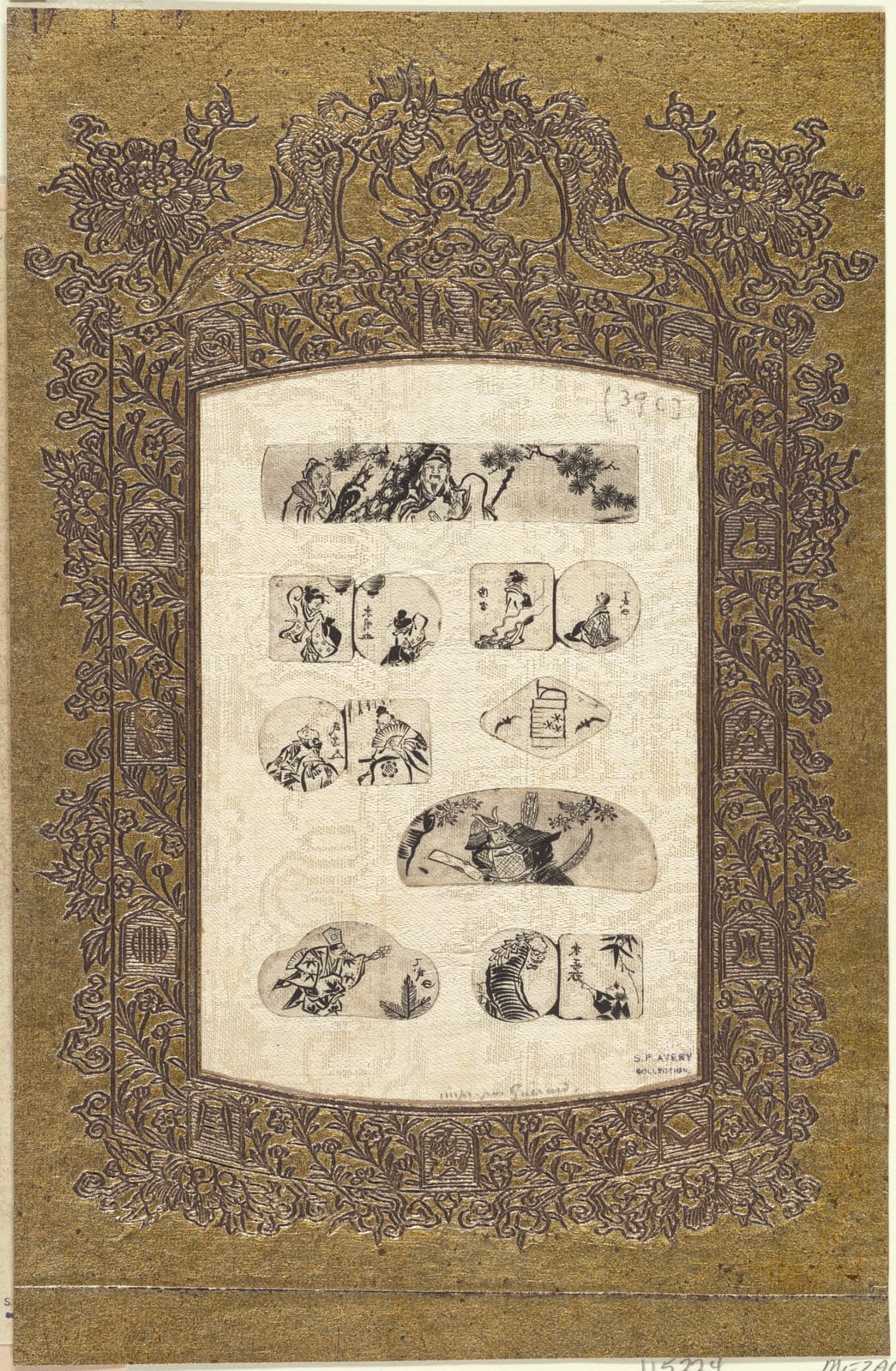

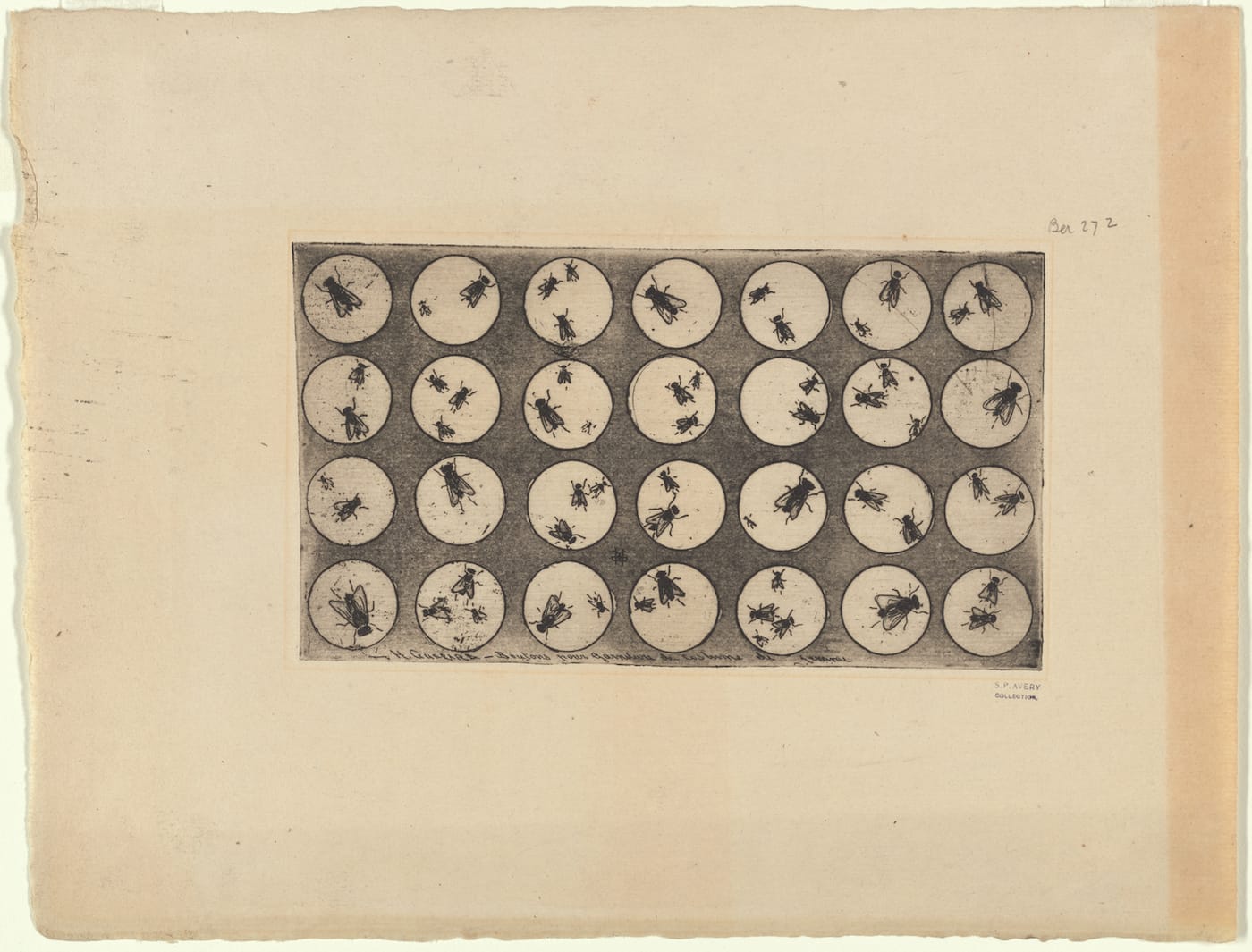

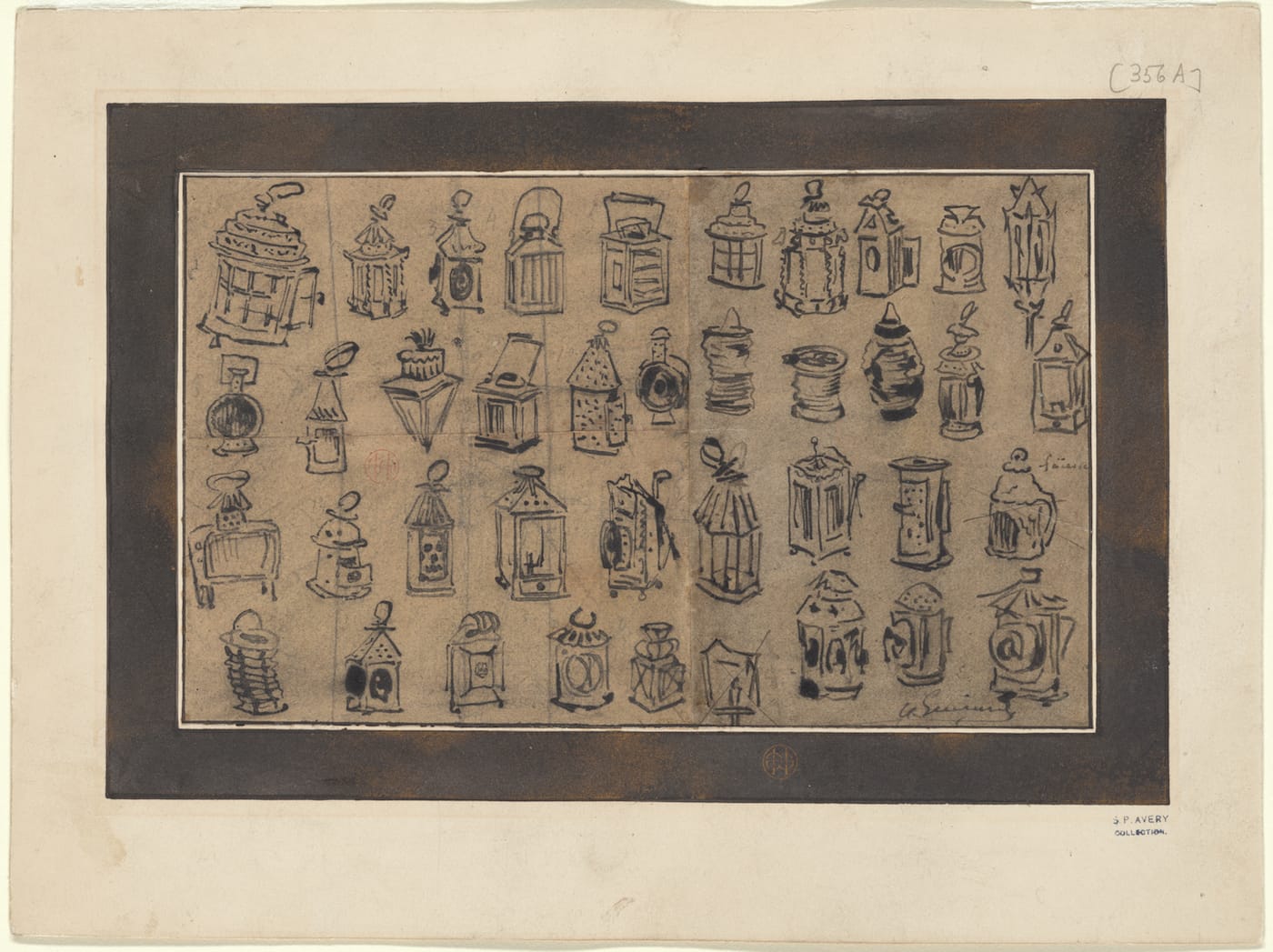

While these reproductions — many of which were published in the literary journal Paris à l’eau-Forte — were highly celebrated, much more compelling are Guérard’s own personal visions. Beside the animal world of dogs, monkeys, cats, and even flies, Guérard’s mind was fixed on the arts of Japan, to which the art historian Louis Gonse had introduced him. Ukiyo-e printmakers from Katsushika Hokusai to Kitao Masayoshi to Utagawa Kuniyoshi inspired the printmaker; he experimented with Japanese paper and incorporated traditional Japanese motifs into his work, from folding screens to fans to lanterns. Guérard actually collected lanterns, and one of his pen and ink drawings depicts dozens of them in a style that evokes the sketches of Hokusai’s famed manga.

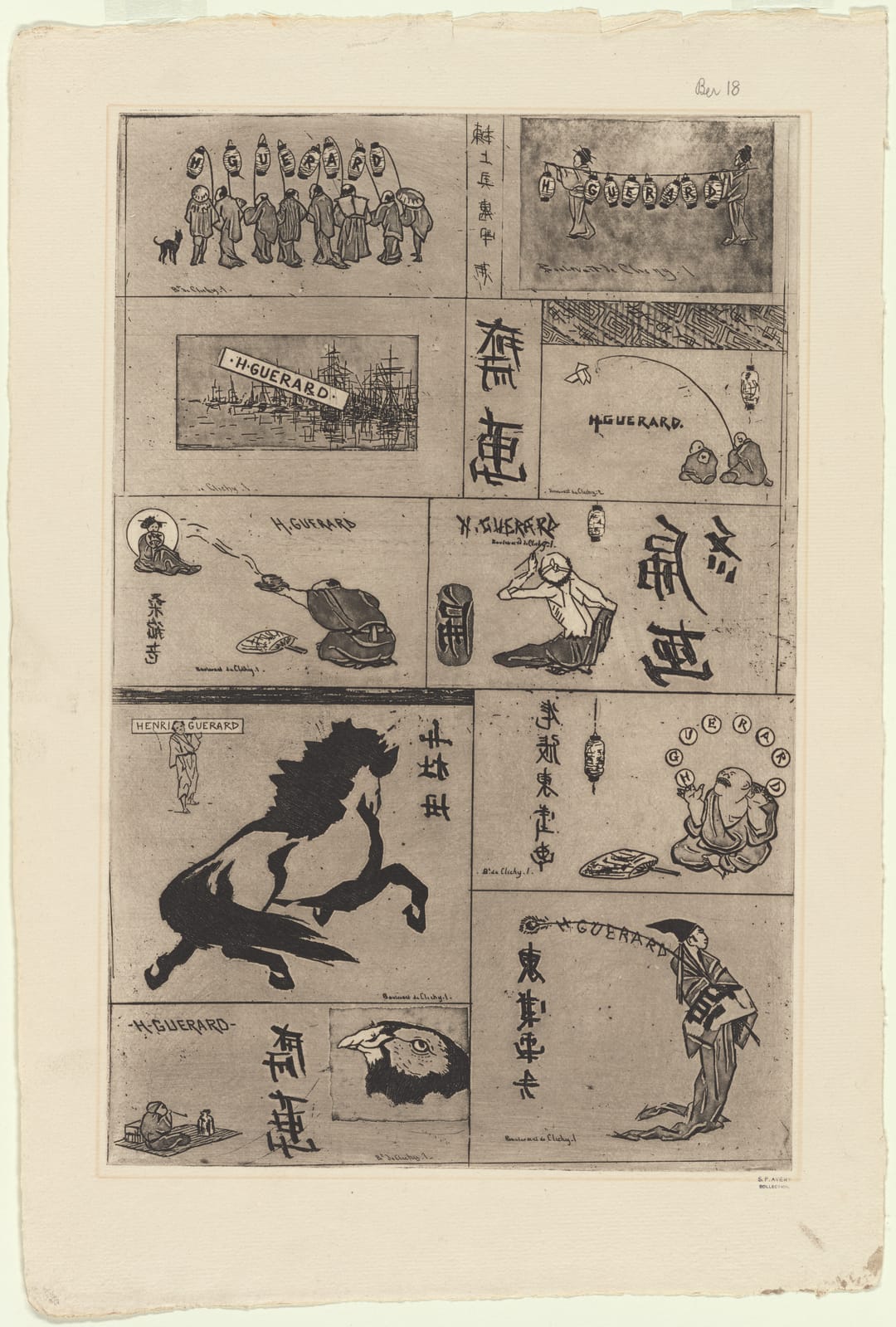

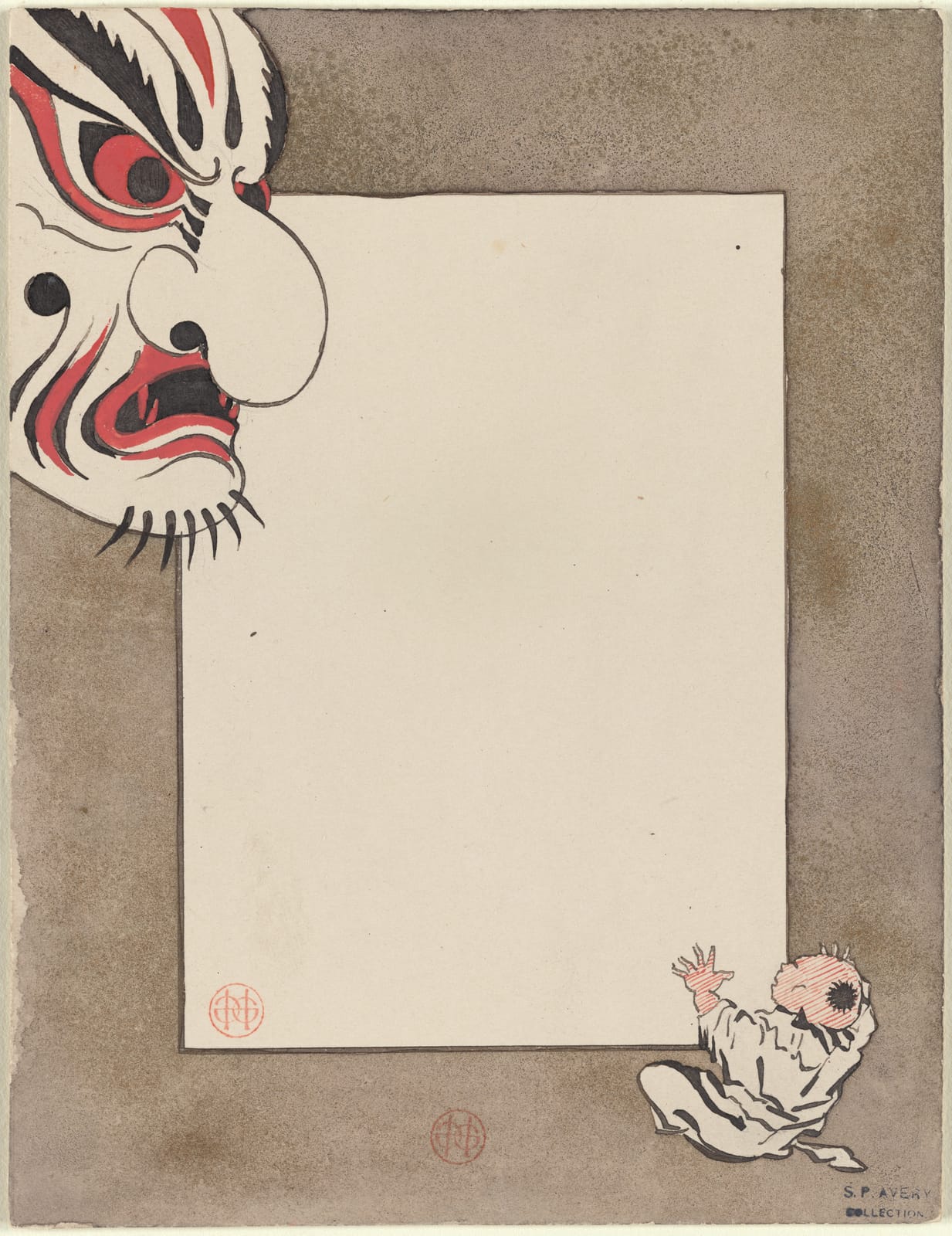

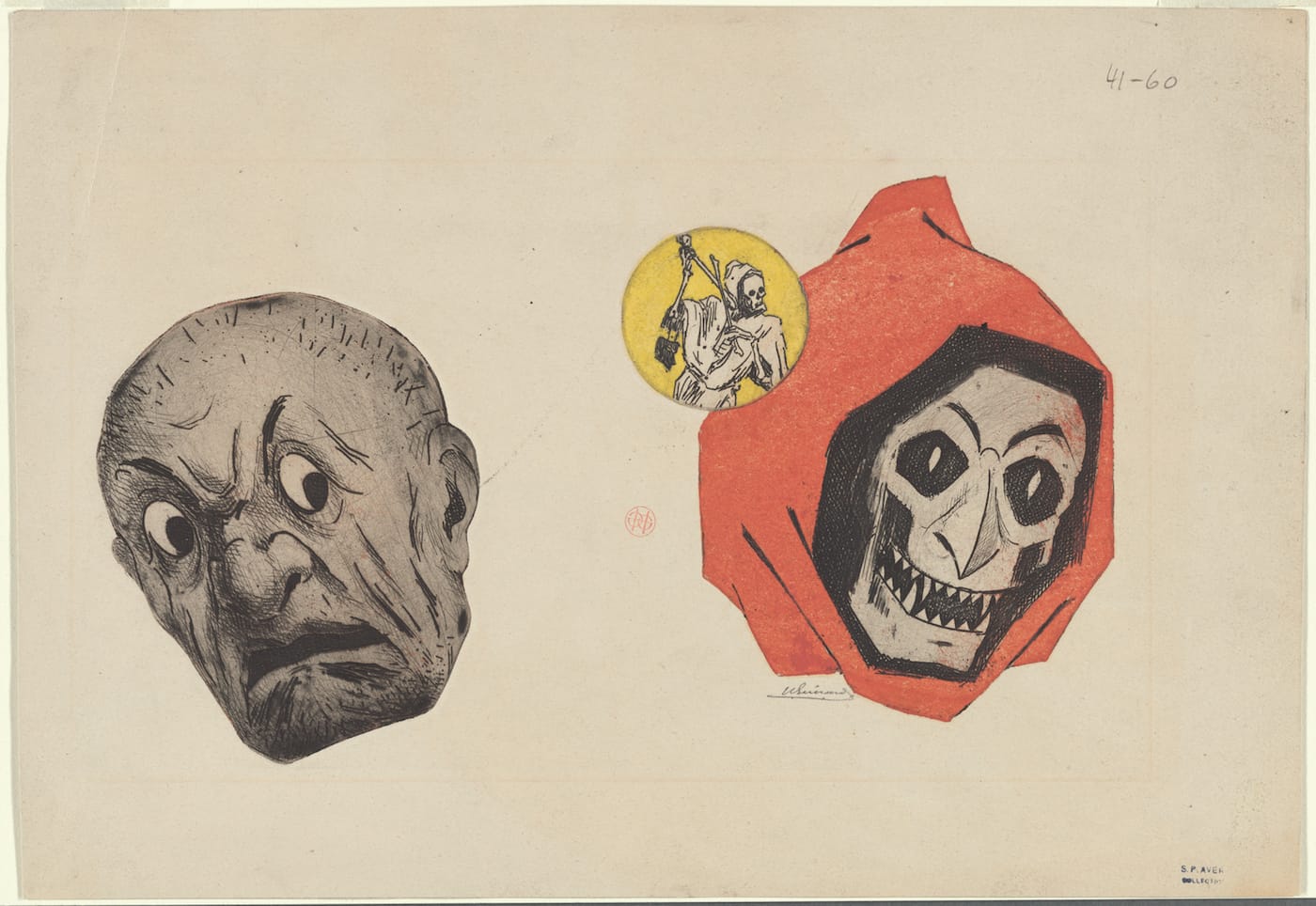

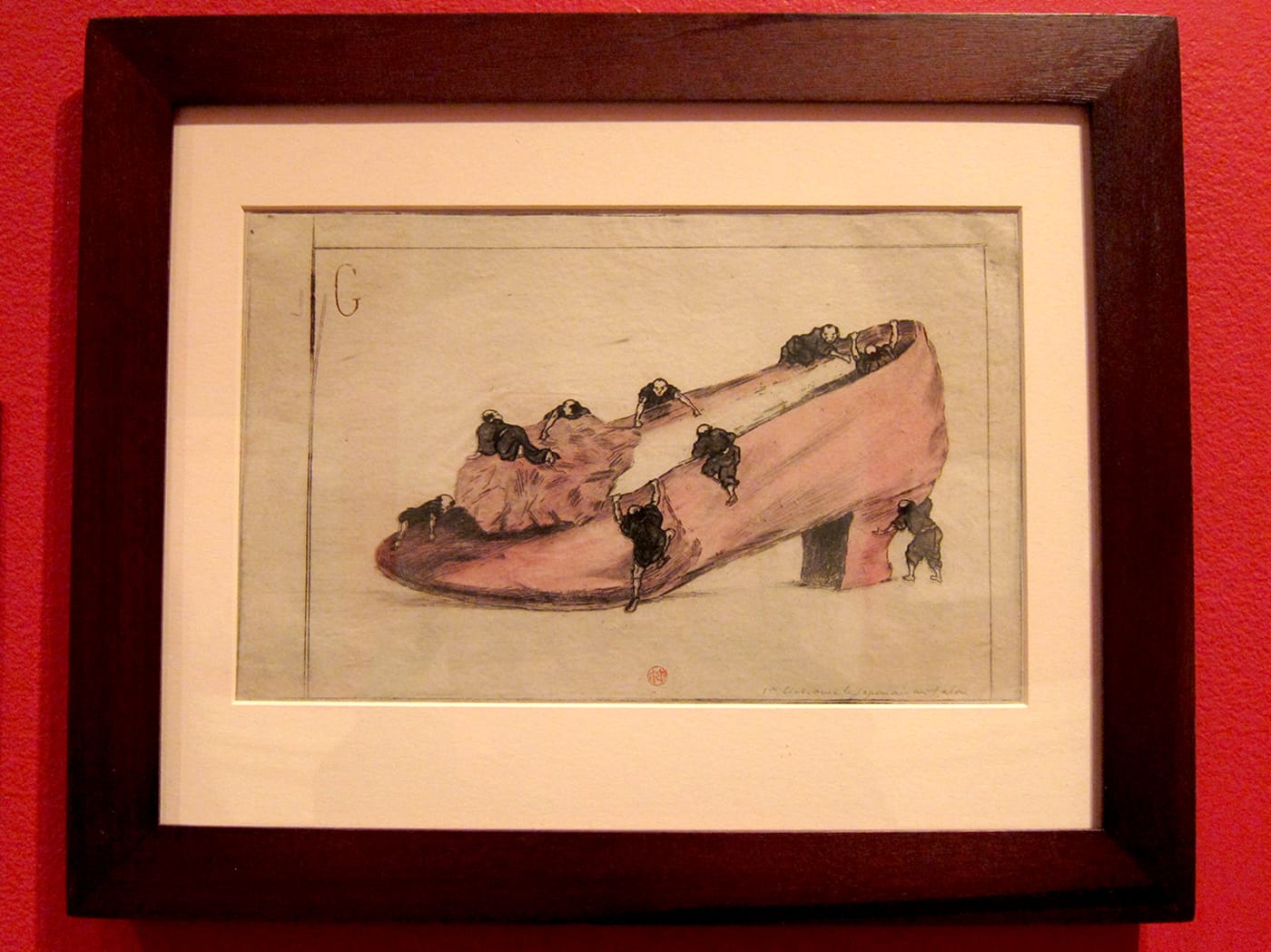

Guérard was particularly drawn to the humorous figures found in the ukiyo-e master’s sketchbooks. These, like Azor, featured prominently in his creations. In a humorous one, little robed men crawl around a woman’s heeled shoe, while one composite work places side-by-side cutouts of a noh mask and a Western personification of death. Guérard often mixed Eastern and Western styles in one image, and the former was clearly integral to his artistic identity: a series of his business cards are dynamic and playful, displaying his name beside Japanese words and common Japanese motifs, from lanterns to fishermen.

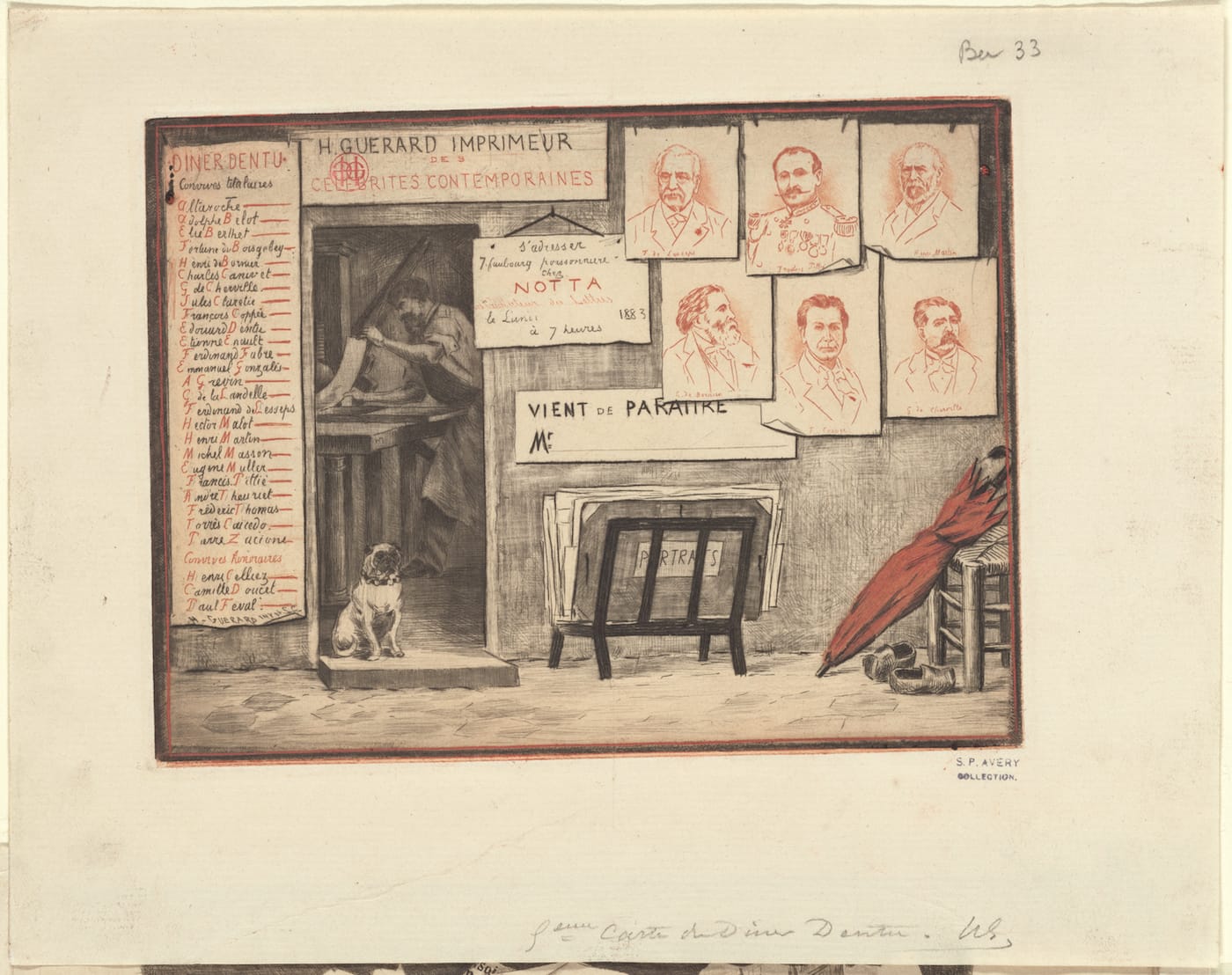

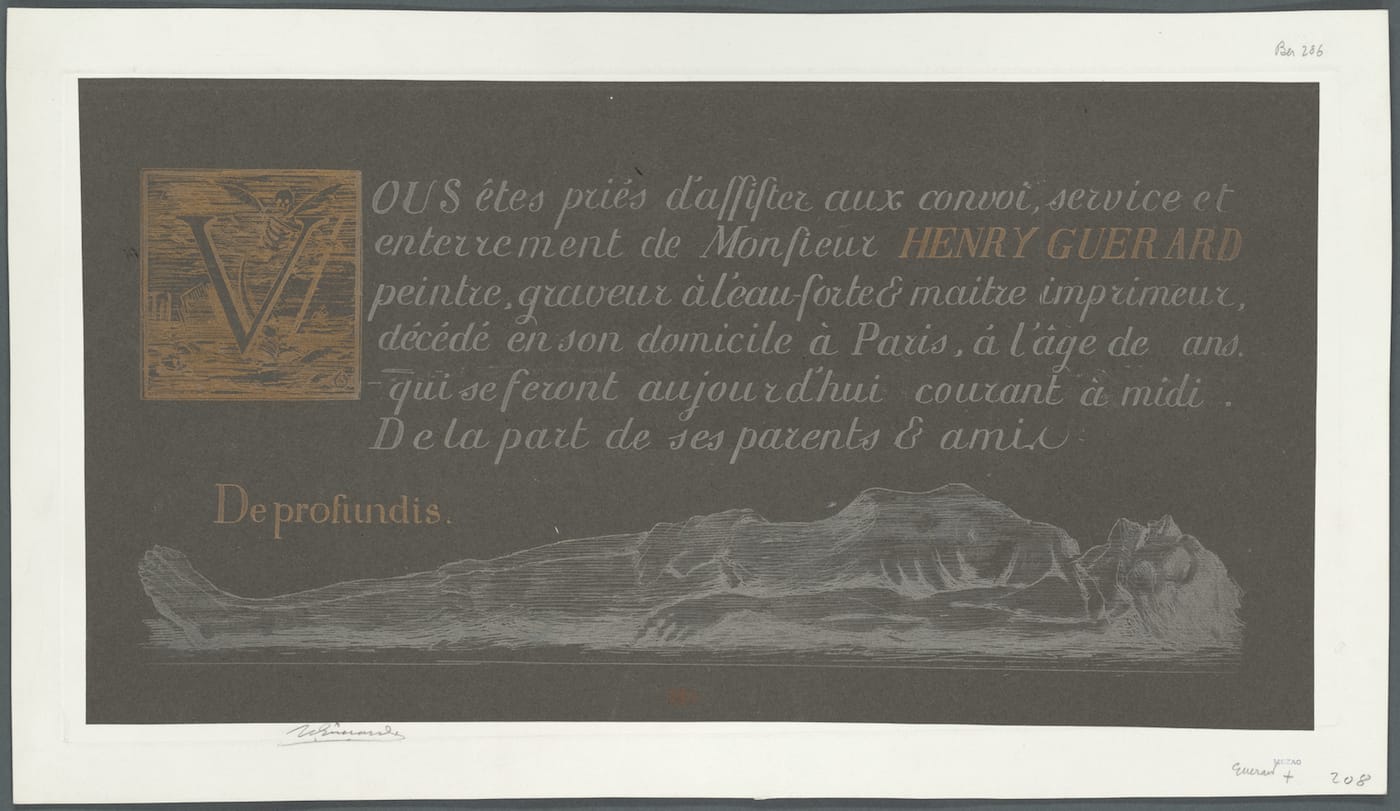

Demand for Guérard’s whimsical works was high: the artist produced a variety of commercial work, from decorated stationary paper to blank cards to menus and announcements. Beginning in 1880, he etched invitations to dinners organized for writers and artists known as “Dîners Dentu” — the first was launched by Henri-Justin-Édouard Dentu, the president of the Society of Men of Letters. No ordinary invitation, these listed the names of guests within charming and intricately rendered scenes. One is a self-portrait, showing a glimpse of the artist in his workspace; sitting patiently at the room’s threshold, next to the event’s roster, is Azor.

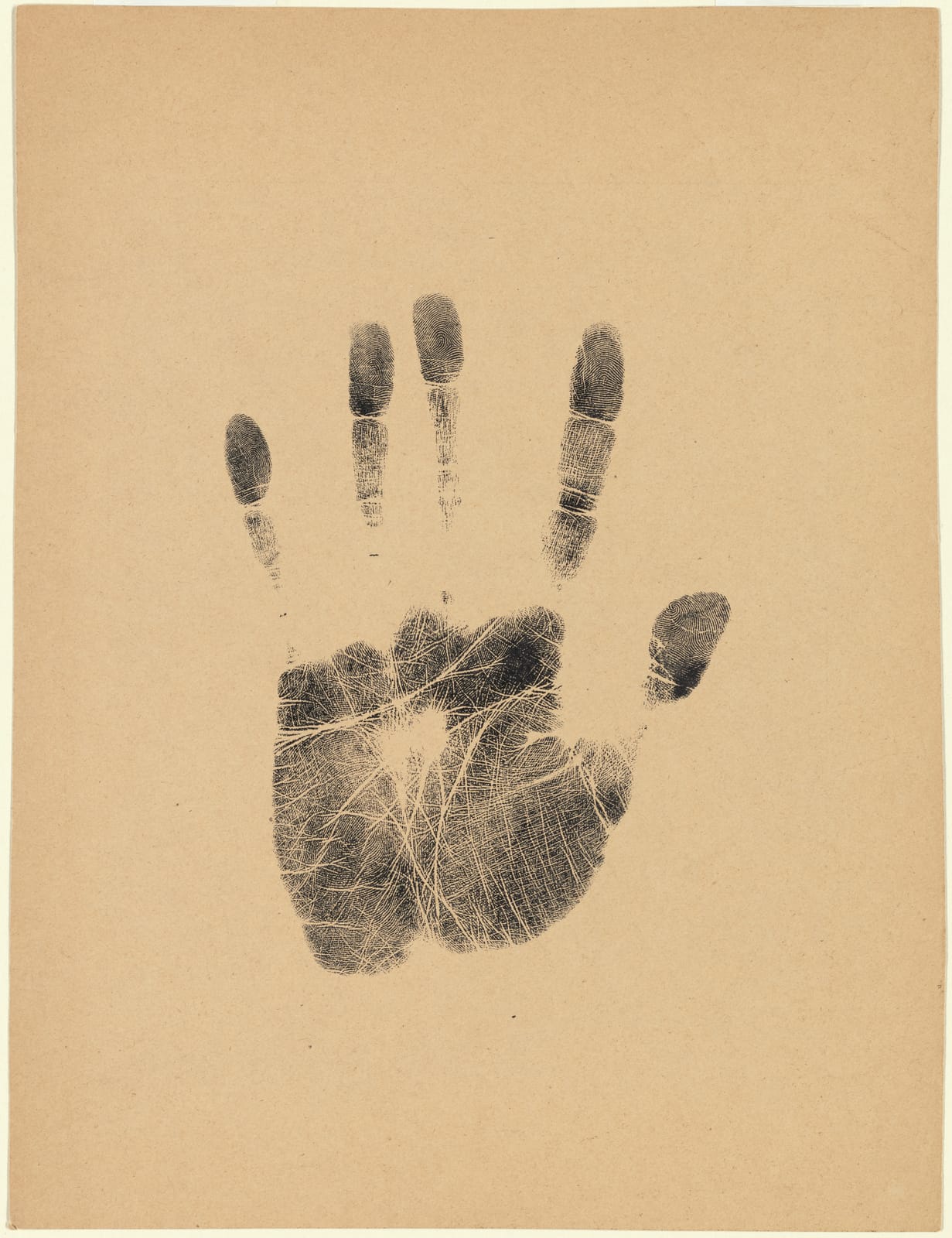

A Curious Hand draws its name from one work that is unlike the others on view: a single handprint, inked as a direct imprint. It records Guérard’s left hand in a time when handprints were starting to be used for crime-solving. But here, centered and striking, it seems more likely a bold statement by the artist. Perhaps it was intended as a self-portrait or, perhaps, an experiment; whatever the reason, Guérard was visualizing the lines on his own hand, making clear a natural kinship between his body and his beloved craft.