From a Depression-Era Mural to Modern-Day Devices, Charting the Rise of Radio

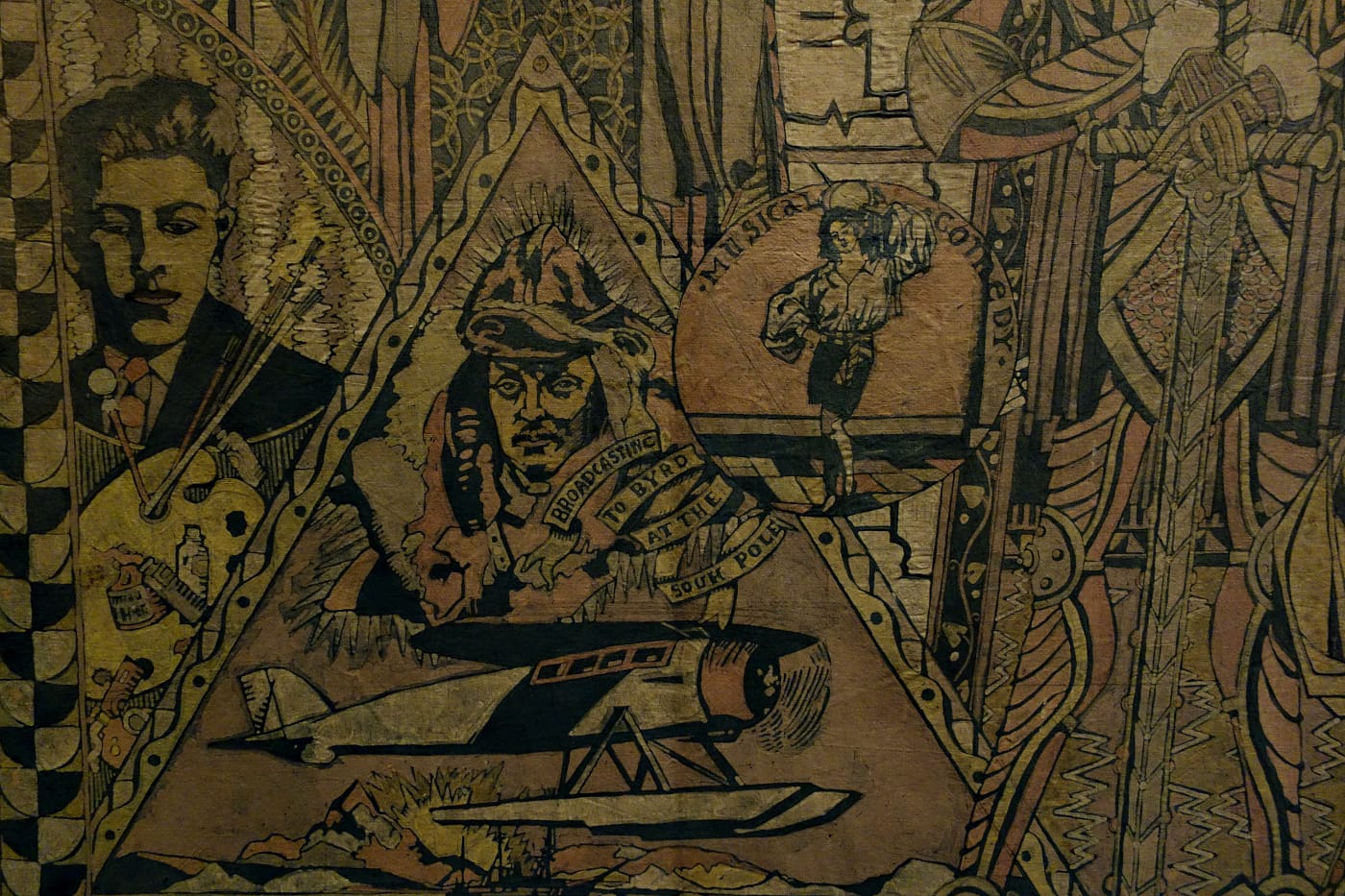

The centerpiece of the Cooper Hewitt's The World of Radio exhibition is a rarely seen, 16-foot-long mural that broadcasts moments from the medium's early history.

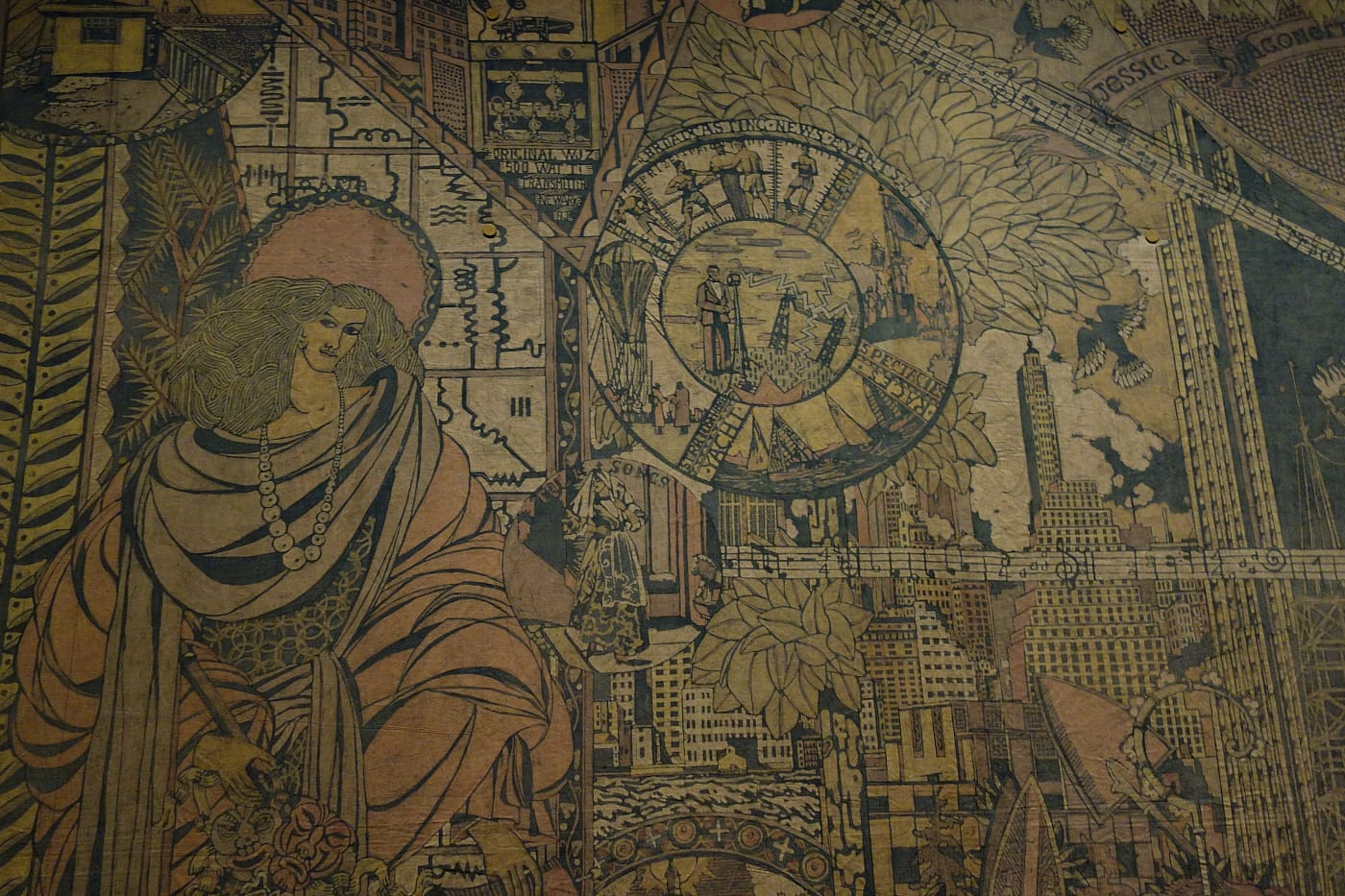

On display for the first time since 1978, “The World of Radio” mural at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, captures 16 feet of radio history, as seen in 1934. When artist Arthur Gordon Smith created the cotton batik work, the medium of communication was still young: Guglielmo Marconi had patented his wireless telegraphy system 38 years earlier. The mural is dense with skyscrapers, steamships, zeppelins, and allegorical figures. It features Richard E. Byrd, who broadcasted from the South Pole; a T-type antenna; and Westinghouse Electric Company’s first radio transmitting station in Pittsburgh. At the center, surrounded by radiating lines of musical notes, a woman in a gown stands on the Earth, preparing to sing into an NBC microphone. She is Jessica Dragonette, a soprano whose performances were heard by millions of Americans in the early days of broadcast, earning her the title “Princess of Song.”

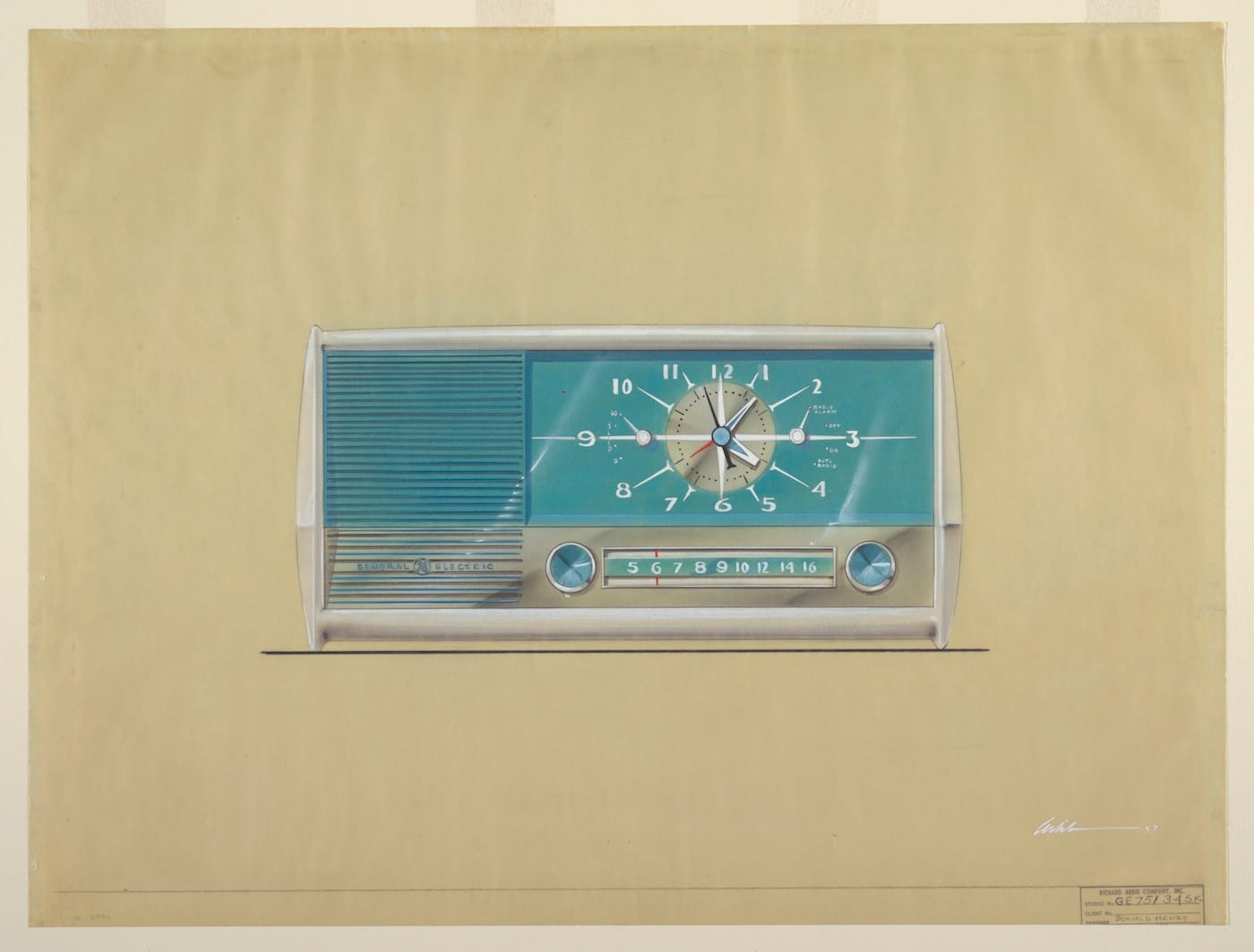

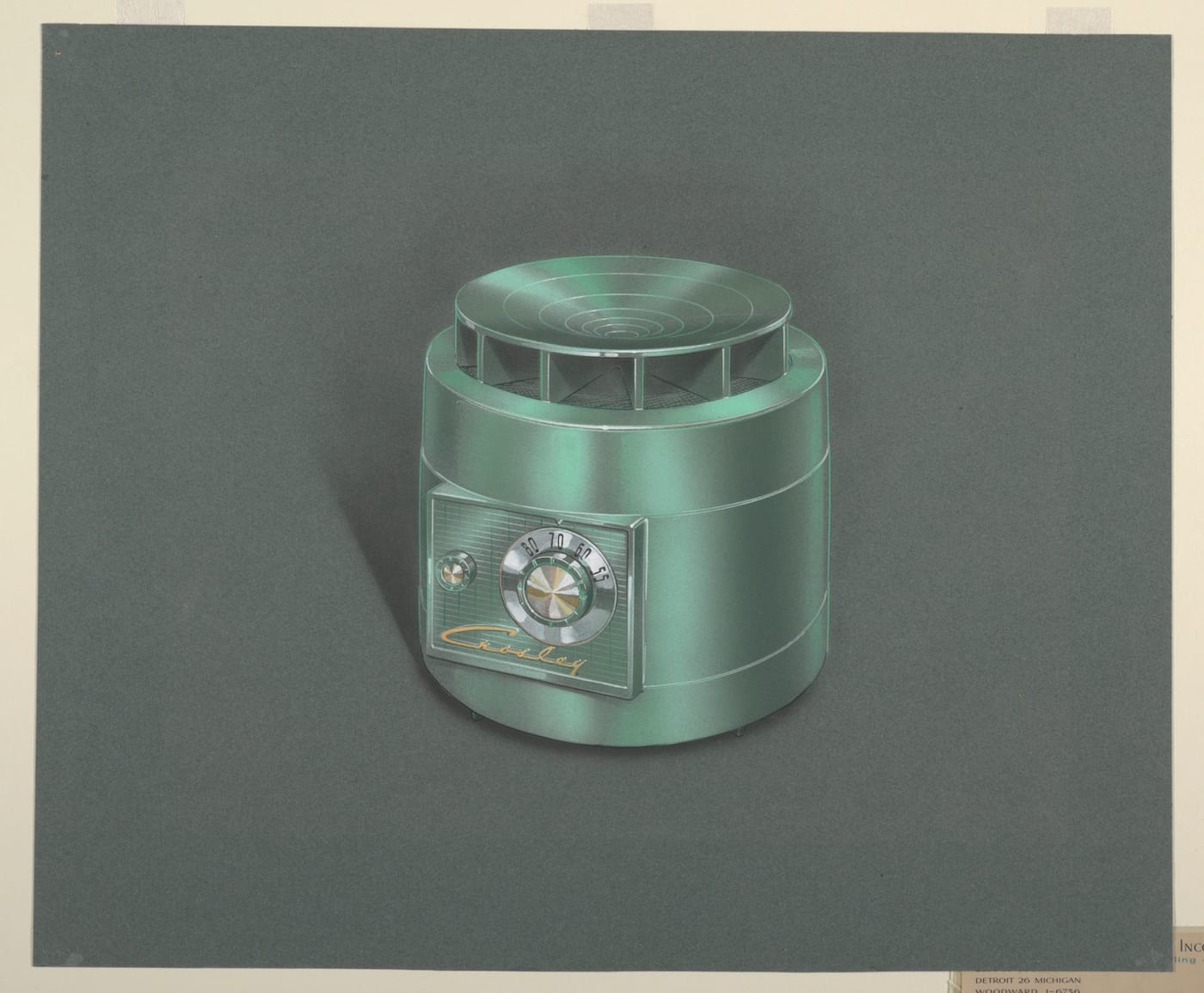

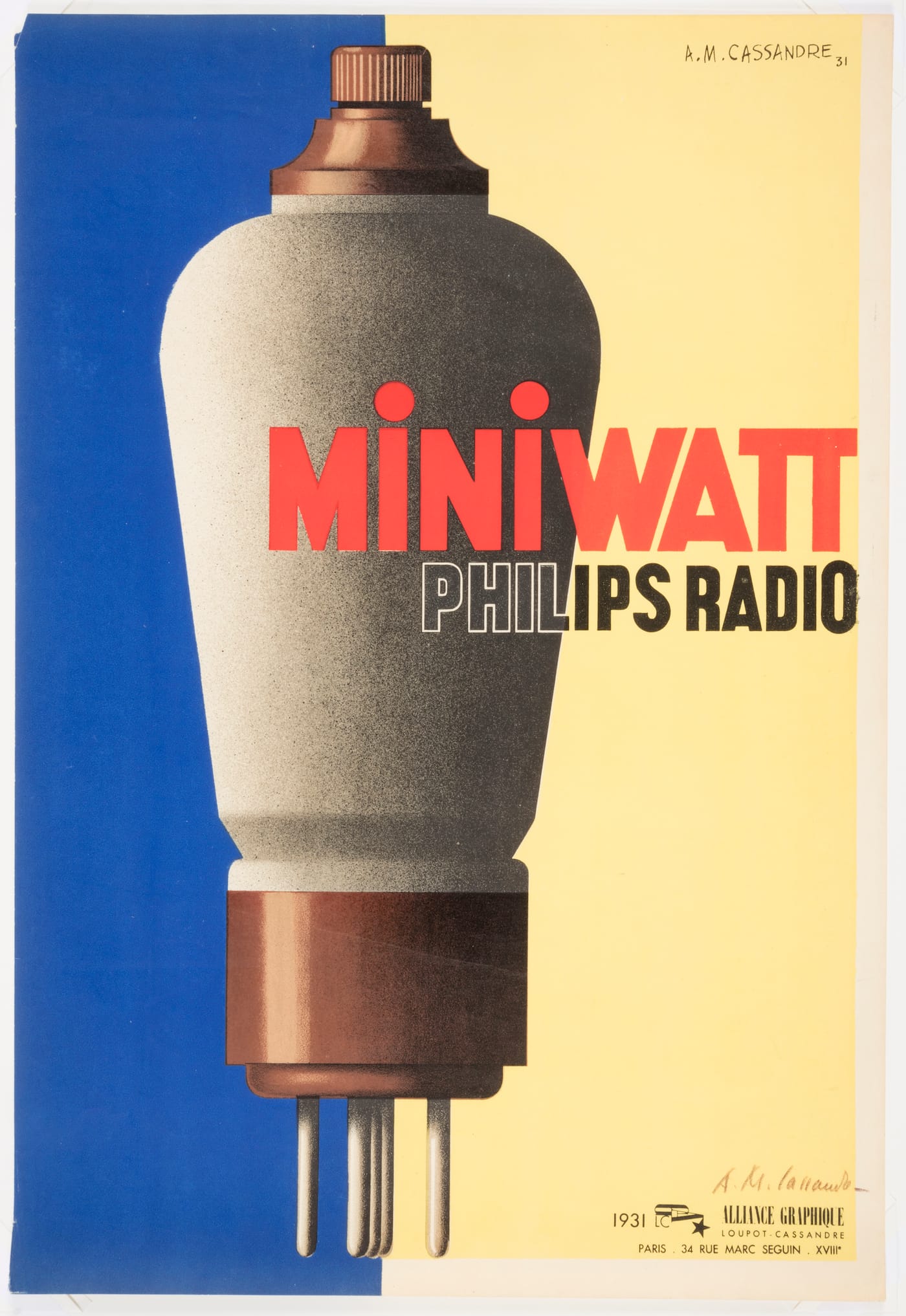

In The World of Radio at the Cooper Hewitt, you can sit on a gallery bench and take in this mural — a gift that once adorned Jessica’s East 57th Street apartment, commissioned by her sister Nadea Dragonette Loftus — while listening to live recordings of her songs. The work is the centerpiece of the show, which explores eight decades of radio technology and design through the museum’s collections. Drawings, consoles, cabinets, and standalone devices demonstrate the development of long-distance communication and entertainment. The small exhibition curated by Kimberly Randall is a complement to the larger The Jazz Age: American Style in the 1920s.

When Dragonette debuted on NBC in 1927, some well-heeled listeners may have heard her voice in their specially devoted radio rooms, like the one shown in a 1927 photograph of pianist Adèle Reifenberg’s apartment. As the decades went on, radios became more compact and affordable, and the examples in The World of Radio go up to the 21st century, such as the 2008 Etón FR 600, intended for emergency use or radio access without power. While that need for connection links all the models, there are aesthetic trends that signal different eras: The 1935 Skyscraper Radio, designed by Harold L. van Doren and John Gordon, has compression-molded plastic angular architecture; the 1950s Crosely radios have speakers that reference the shapes of curvy automobile grilles; and the 1961 Tischsuper RT 20, designed by Dieter Rams, has a minimalist style and a boxy shape combining metal, wood, and plastic.

With the mass adoption of the medium came a new form of propaganda power, as represented by 1933 and 1938 versions of the Volksempfänger, or “people’s receiver.” The cheap line of radios, which only tuned into local stations, was launched at the request of Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, so that the Third Reich could speak directly to citizens in their homes. On the other side, Dragonette was heavily involved with the American WWII effort, singing for troops and to sell war bonds. Although she mainly retired from the air after her marriage in 1947, the 1934 mural immortalizes her in the moment when she was on top of the broadcast world.

The World of Radio continues at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum (2 E 91st Street, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through September 24.