Tracing the Legacies of Postwar UK’s Lost and Damaged Public Artworks

Last December, after cultural preservationists in England realized that many of the nation's postwar public sculpture have disappeared from the landscape over a number of decades, they issued a public call to attempt to trace or even recover them.

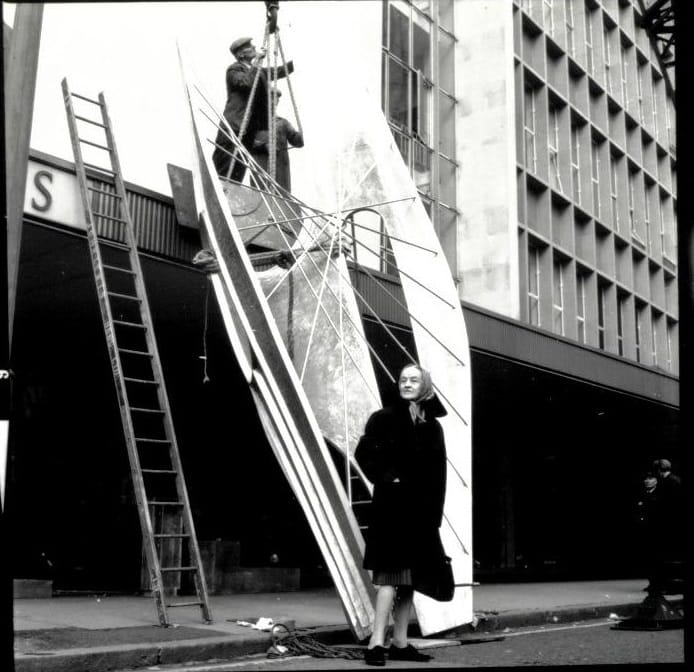

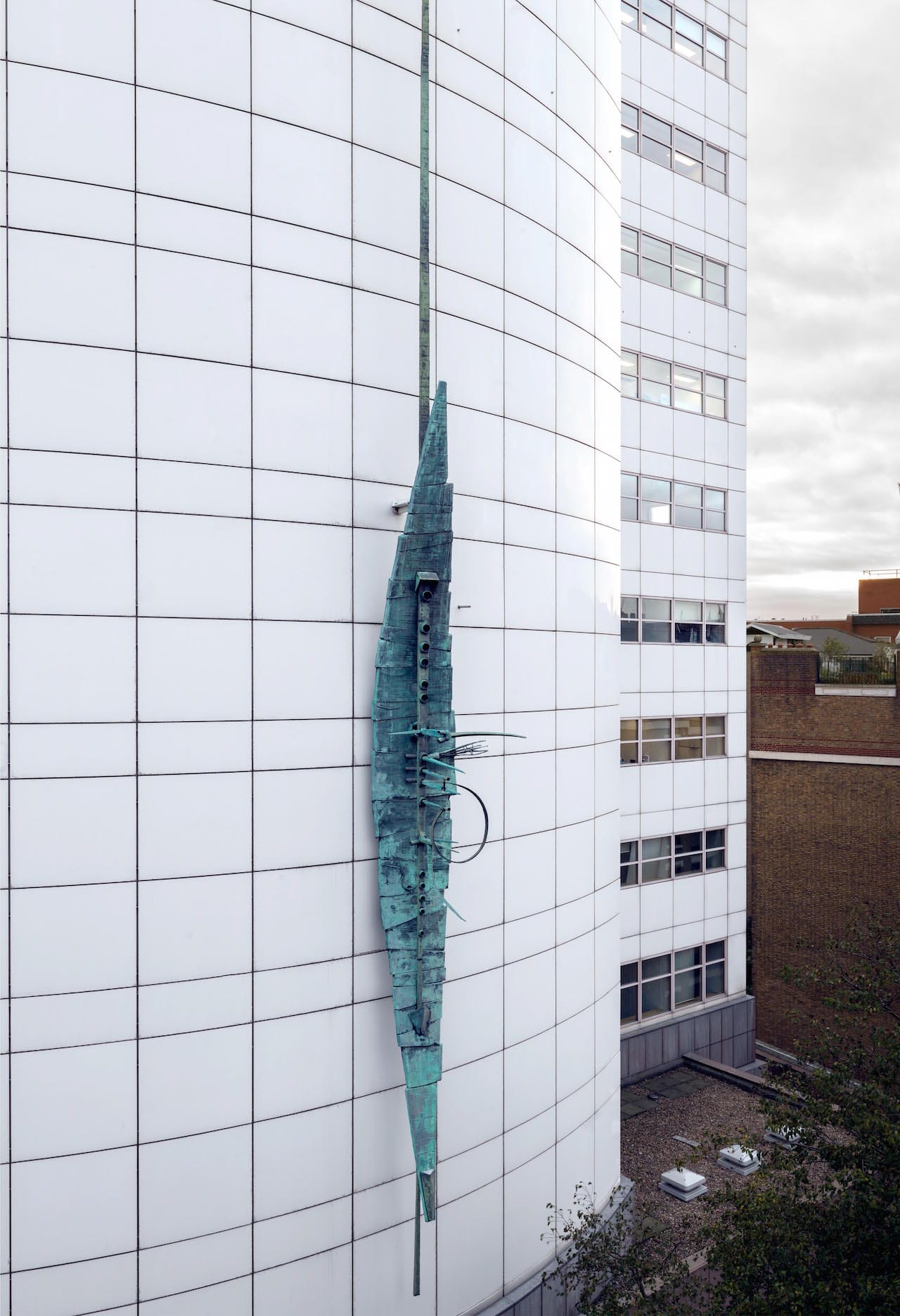

Last December, after cultural preservationists in England realized that many of the nation’s postwar public sculpture have disappeared from the landscape over a number of decades, they issued a public call to attempt to trace or even recover them. Historic England (HE) — a public body charged with protecting the country’s historic environment — had discovered that theft, vandalism, suspicious sales, or other mysterious incidents have removed many commissioned works from their original sites. Along with developing a database of lost and destroyed public art, it also last month created new listings of 40 postwar sculptures that mark them as historic and gives them extra protection. It includes the first Antony Gormley to be listed (a figure cupping its ear to listen to its surroundings), an early two-piece bronze by Henry Moore, Edward Paolozzi’s towering “Ventilation Shaft Cover” (1982), and three works by Barbara Hepworth. The vulnerability of public works became increasingly clear during HE’s research, prompting the creation of Out There: Our Post-War Public Art, an exhibition at Somerset House, to remember lost works between 1945 and 1985 and revisit their histories while building awareness of the threats to public art.

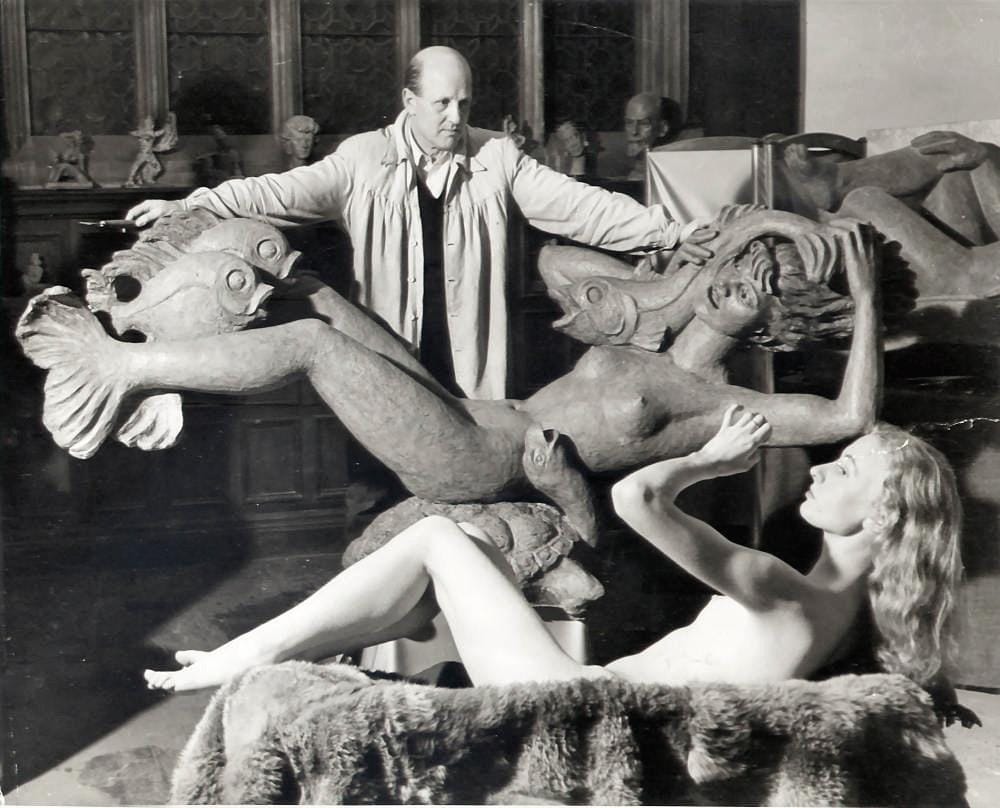

Created for the outdoors such as spaces in parks and areas by housing projects, schools, and hospitals, these sculptures emerged as part of a huge postwar construction boom, as curator Sarah Gaventa told Hyperallergic.

“They were part of an ambitious program to bring art to the people, instigated by the post-war labor government and the newly formed Arts Council and local authorities who were encouraged — by the Ministry of Education, for example — to commission art to improve the local environment for the public,” Gaventa said. “The new subject matter was more relevant to the public and their lives. It was also a form of social engineering to encourage certain behaviors … representing civil harmony and peace.”

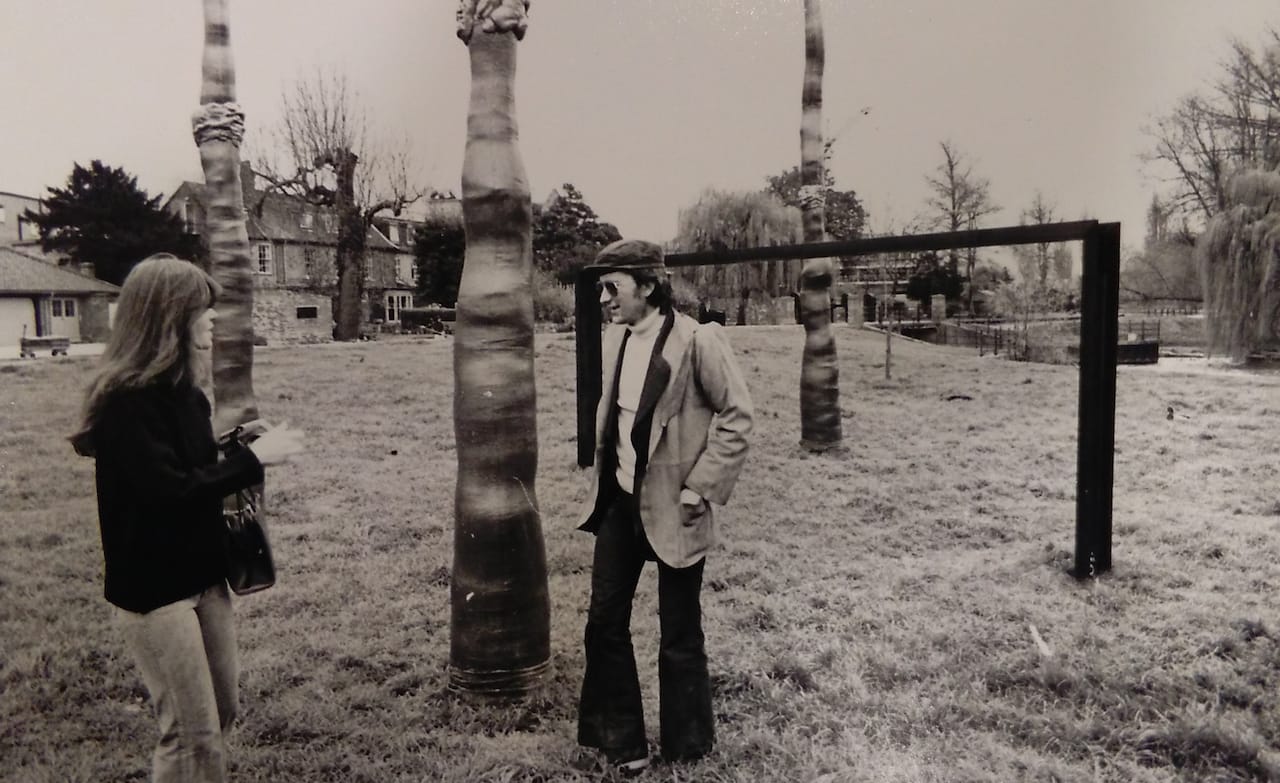

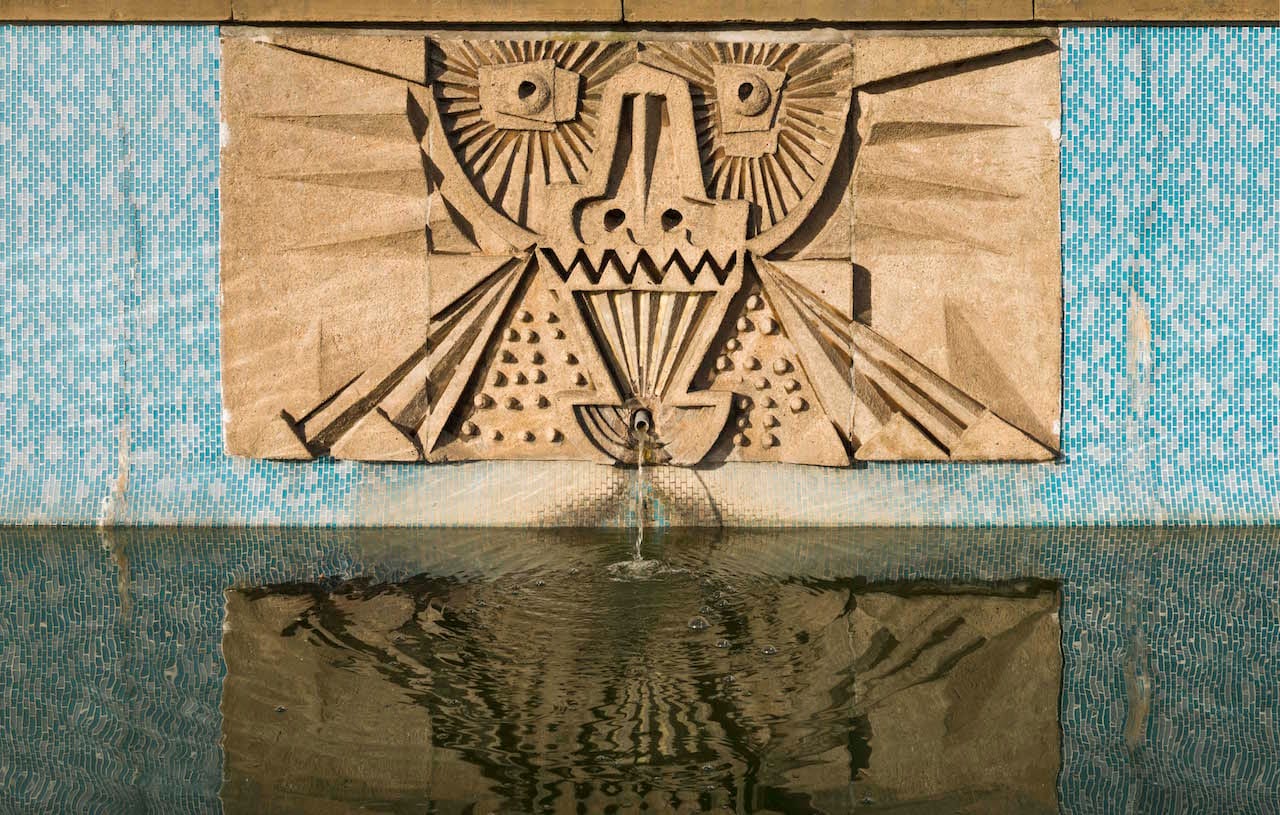

Unfortunately, many of these works instead became targets of social disobedience, treated as canvases for graffiti or seen as pieces of scrap metal freely available for selling. Many of the sculptures the exhibition remembers — through photographs, drawings, documents, and maquettes — are confirmed as destroyed. At times it was public dissatisfaction that led to sorry fates: Barry Flanagan’s “The Cambridge Piece” (1972), for instance, was not well received and experienced multiple wounds from vandals until it was beyond repair. One local vicar had apparently also written to the press and asked that those in charge “blow up revolting art!” Other sculptures simply stood in the way of development projects, such as William Mitchell’s “The Spirit of Brighton” (1968), whose own custodians — Standard Life Investments — demolished the sand-blasted piece without consulting anyone to make way for a shopping center.

![Antony Gormley, "Untitled [Listening]" (1983-84) at Maygrove Peace Park, London (© Historic England)](https://hyperallergic.com/content/images/hyperallergic-newspack-s3-amazonaws-com/uploads/2016/02/gormley-maygrove-peace-park-image-1.jpg)

The heavy weights of many of these sculptures also did not fail to deter thieves from making off with them. A large reclining figure by Henry Moore disappeared in 2005 while being prepared for an exhibition in Japan, with police believing the £3 million (~$4.1 million USD) work was melted down for scrap in exchange for £1,500 (~ 2000 USD); one of Lynn Chadwick’s figures in “The Watchers” (1960) was separated from the sculptural trio in 2006, sawed off at its feet. Police estimate that at least eight people had to be involved to cart away the over six-foot-tall piece.

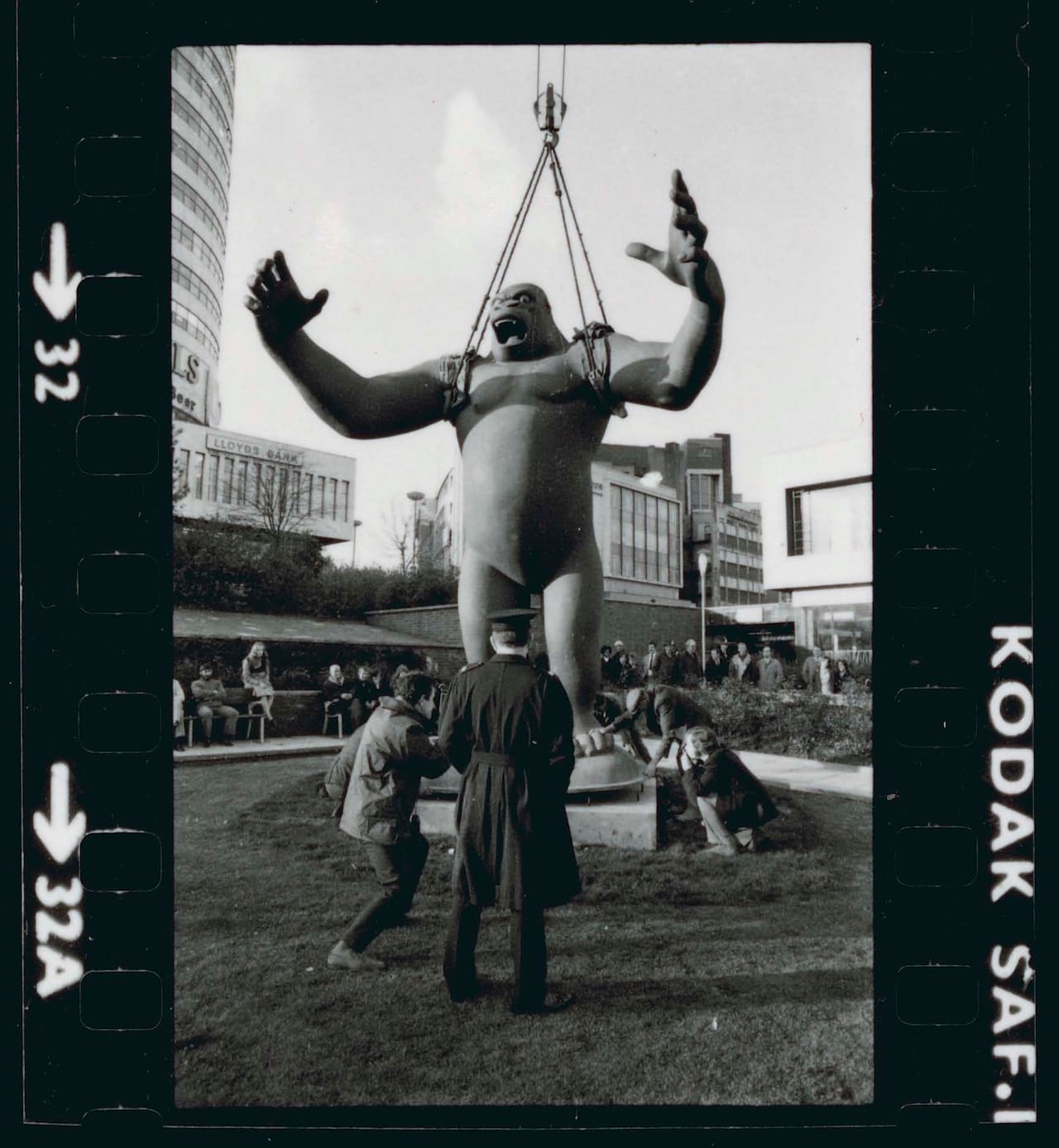

Pieces with such murky pasts are marked as “lost” or “disappeared,” and they appear on a wall in the exhibition like missing people or pets, displayed in the hope that someone may have tips concerning their whereabouts. Although intended to be site-specific, these sculptures have ended up traveling, making tracing them an arduous process. Nicholas Monro’s giant “King Kong” gorilla, for instance, created for the 1972 City Sculpture Project, moved multiple times, was subject to numerous cases of vandalism, and even experienced makeovers — from a pink paint-job to a Santa Claus disguise. Furthermore, no database ever existed of all the work from this period, as Gaventa said, and their histories were never recorded. Although Historic England at times has tracked some of these sculptures to private homes, auctions, storage rooms, or temporary sites for repair, sometimes the trail of evidence ends and only questions remain.

Thanks to a lot of detective-like work spearheaded by Gaventa and members of HE, however, some of these previously missing works have turned up. Aside from spending a lot of time in archives digging through uncatalogued boxes to try and learn about their stories, the team was also in contact with private collectors, some of the artists, and the artists’ families. Because of these endeavors, they have found some casts of lost works and even recovered some original sculptures that are on display in Out There. One successful find is a massive fiberglass relief by Paul Mount, which was marked for removal from a supermarket it decorated but later saved from destruction. Similarly, the fate of another relief by Trevor Tennant, which once adorned the entrance hall of a hospital, was threatened by the institution’s closure until a doctor recovered it. As such stories, along with Gaventa and HE’s own efforts exemplify, the efforts and knowledge of individuals are instrumental to bring back work originally intended to be accessible to all. Out There hopes to make their value as pieces of artistic heritage clear and appreciate and to prevent any future need to embark on complicated searches.

“The public needs to rally around local work to protect it, suggest pieces for listing to HE,” Gaventa said. “If a piece is no longer able to stay in its original home – a new location should be found for it, rather than it being scrapped or destroyed during demolition of a building, which often happens simply because it is the easiest option.

“This heritage is irreplaceable,” she said. “It reminds us of a more ambitious age of equality and hope — and it needs our protection.”

Out There: Our Post-War Public Art continues at Somerset House (Strand, London WC2R 1LA, United Kingdom) through April 10.