Unpacking Trauma by Examining the Bullet that Caused It

The video essay is Vanessa Gravenor’s attempt to make sense of her trauma, which remains serpentine, meandrous, never subsiding, ever present.

Dawn came on us like a betrayer; it seemed as though the new sun rose as an ally of our enemies to assist in our destruction […] then I wrote … I acquired the vice of writing.

―Primo Levi

BERLIN — Survivors of terrorism often describe a strangely beguiling paradox when, after bearing witness to absolute evil and being confronted with the task of giving testimony to it, they must return to the “real” world of events, which can seem utterly fictitious, futile, even backward. In the case of Primo Levi, who confronted the horror of surviving 11 months in the abominable Polish concentration camp Auschwitz, he lamented that victimhood brought with it a responsibility for giving testimony to the bereavement that he and other survivors faced.

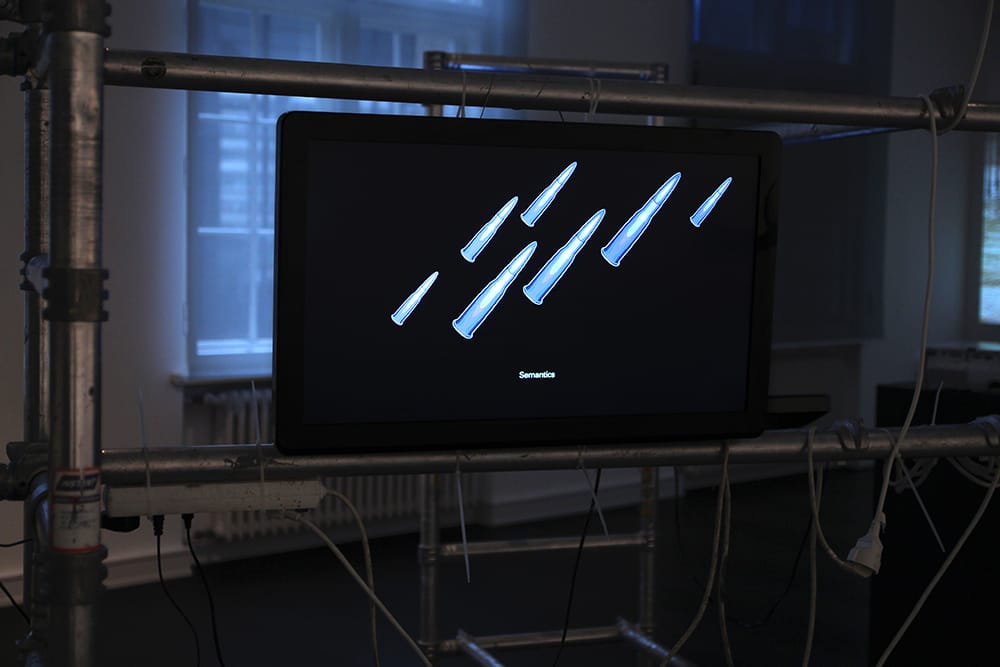

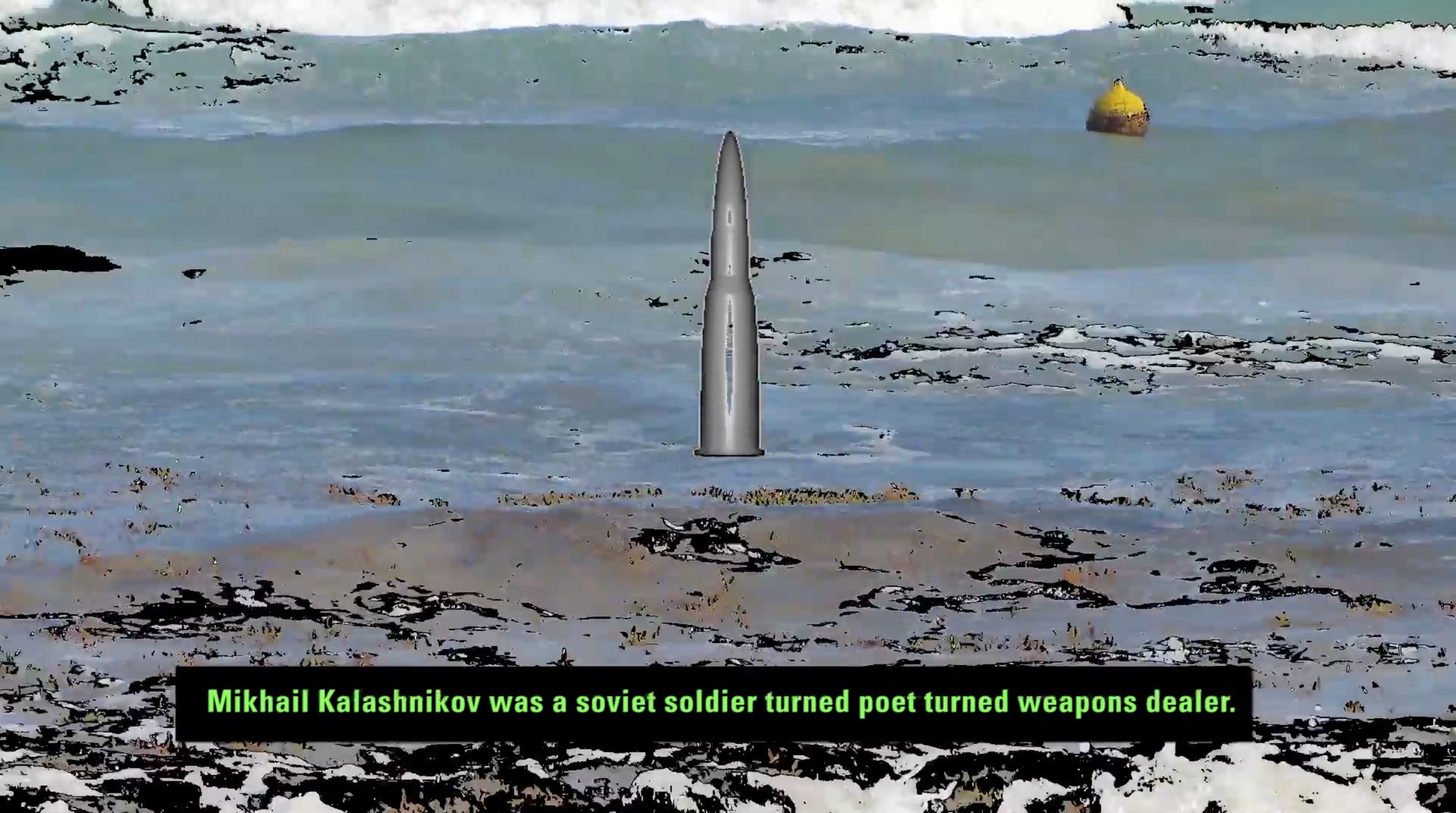

The recent exhibition ON OFF SHORE, curated by Paul Feigelfeld at the Helmut Newton Foundation, displayed one particular work that exemplified Levi’s paradox. “Me / My Bullet” (2016), by Canadian artist Vanessa Gravenor, examines the history and context of the Kalashnikov bullet, set against the artist’s subjective response to having encountered one in the November 2015 Paris attacks. In an unpublished essay, Gravenor recounts:

On November 13th, 2015, I was injured in the Paris attacks at the first location members of ISIS hit at roughly 9:35 in the evening. It was by a stray or direct bullet. I can’t remember when in the sequence of trying to hide it happened, I just know it did, and that knowing took on a type of bodily meaning.

Often, from the experience of the victim, the event of being targeted, persecuted, and shot creates a hierarchical experience of reality, where everything before and after feels less real than the event itself. The video essay is Gravenor’s attempt to make sense of her trauma, which remains serpentine, meandrous, never subsiding, ever present. Set to a discordant remixed version of Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” and featuring a CGI rendering by Hiba Ali of the Kalashnikov bullet, Gravenor situates the destruction wreaked on her body within the historical context of the bullet’s manufacture. After the fall of the Soviet Union, the black market proliferated with illegal arms like Kalashnikov rifles and ammunition — weapons that are now, unsurprisingly, a staple in urban terror. Kalashnikov bullets now feature in terrorist plots, the Middle East, Afghanistan, Iran, and Syria, coming back “like phantom memories,” as the artist states. “Me / My Bullet,” on one level, reminds us of the gap between innocence and experience, told from the perspective of the victim rather than an outside observer. On another level, the work speaks to Gravenor’s skill as an emerging young artist concerned with confronting difficult and timely issues.

Gravenor’s astonishing yet chilling piece is accompanied by several other works in the exhibition that are much less visceral, distressing, or macabre. The show was conceived as a way of way of condensing issues and undercurrents around migration, of which terrorism is just one part. The ambitious exhibition brought together young artists whose work seeks to map alternative critical perspectives in contemporary art, dealing with subjects from personal memory and data to displacement and mining for natural resources.

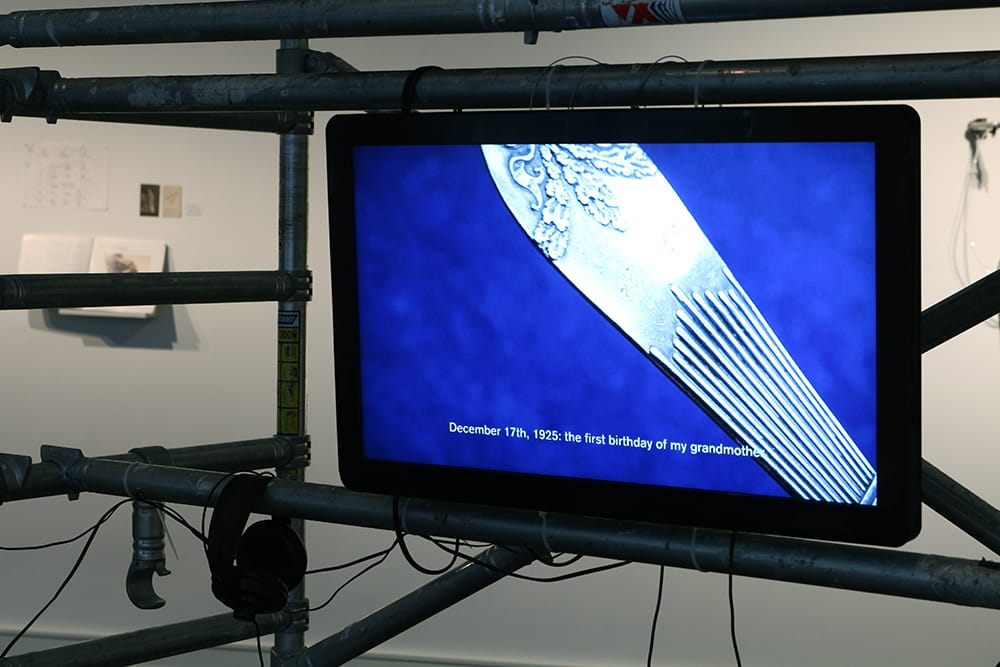

For example, in Stefanie Rau’s “Feeding Back (Or: And still we keep holding on to our spoons)” (2016), a video essay about a spoon bequeathed to the artist by her deceased grandmother, the artist conceived of the object as containing both personal and collective memory while still being, from an outsider’s perspective, simply something pragmatic. Rau then connects the spoon with the idea of the internet, suggesting that both can be seen as personal and utilitarian. It is, in effect, a work that bridges a gap not always explicit: that between individual memory and the universal experience of loss.

Ultimately, the exhibition felt like a total deprivation of innocence. All the works on display seem to contain some measure of trepidation, whether about the looming specter of terrorism, personal loss, or ecological disaster, permeating each with a feeling of fear and anxiety about the future. Consequently, the show seemed to foreshadow the uncertainty following the recent election of Donald Trump, attesting to the ability of artists to bear witness to contemporary discomposure.

ON OFF SHORE was on display at the Museum für Fotografie (Jebensstraße 2, 10623, Berlin) through October 30.