Visions of Venezuela and Cuba From Exile

An exhibition near Washington, DC, offers an immersive reclamation of memory and identity in all their fluidity and impermanence.

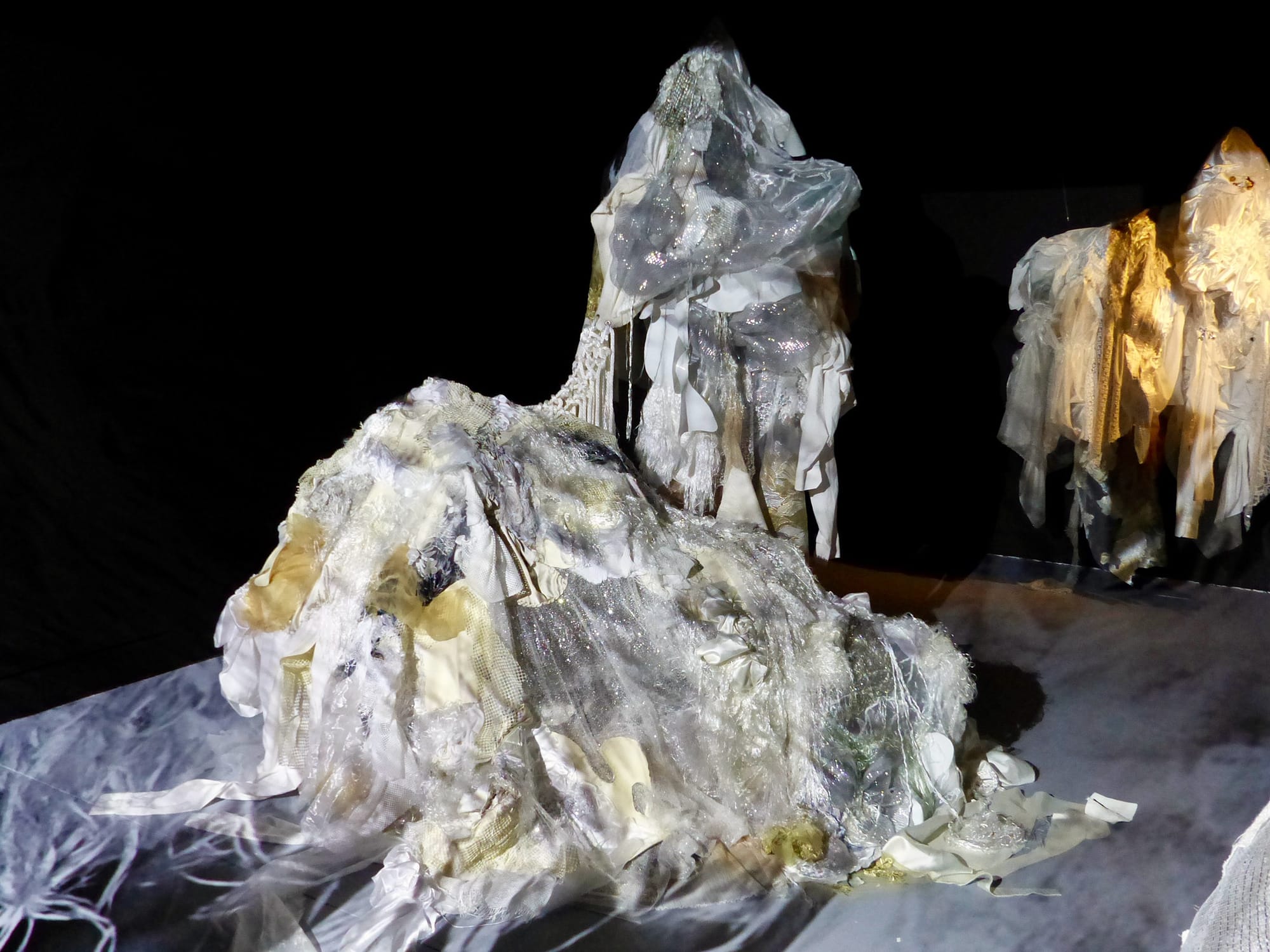

ARLINGTON, Va. — Otherworldly forms greet you at the entrance to the exhibition, transporting you into a kaleidoscopic, dream-like space. A voice speaks in the background as projected images dance across the forms, animating the space. “It's been really beautiful to see her work come alive, become a landscape … where you can traverse and kind of get lost,” curator Fabiola R. Delgado says of Lisu Vega’s “The Uncertain Future of Absence (El Futuro Incierto de la Ausencia)” (2025). Vega's work is on display in Tactics for Remembering, on view through January 25 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington, along with those by Reynier Leyva Novo and Amalia Caputo.

Shortly into the new year, the Trump administration carried out strikes on Caracas, Venezuela, and abducted President Nicolás Maduro. Maduro’s removal brought relief to many Venezuelan expats. But coupled with legally dubious boat strikes, detentions, and deportations already dominating recent headlines around Venezuela and the Caribbean, fear and confusion continue to radiate outward from DC to diasporas in the region. Located just a few miles from the nation’s capital, where Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other federal agents patrol the streets, this exhibition stands in stark visual and narrative contrast to the bluster of dueling authoritarians, possible regime change, renewed repression, and domestic immigration crackdowns by inviting visitors to explore other perspectives. R. Delgado planned this exhibition long before the Trump administration’s machinations to showcase the works of Venezuelan and Cuban artists through a Caribbean lens. There’s no overt activist messaging in the artworks, but the circumstances surrounding this exhibition, both in terms of physical proximity and timing, impart new meaning for viewers to consider.

The region encompassing the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia (DMV), home to a growing number of Cuban and Venezuelan diasporic populations, has seen more than 940 immigration arrests just between August and September, and a 350% increase in ICE arrests in the state of Virginia in the past year, leading to a palpable unease in the area. As the Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela (CHNV) humanitarian parole program allowing nationals to apply for a temporary two-year stay in the US was revoked this past summer, Temporary Protected Status (TPS) terminated for Venezuela in November, and new green card and citizenship applications also recently halted, more communities are at risk due to a sudden loss of protected status or legal residency. That risk is amplified by the uncertainty surrounding Venezuela’s recent upheaval, with mixed emotions and prospects for the future, as well as corresponding threats to other countries in the region.

The works in Tactics for Remembering speak directly and implicitly to the fundamental nature of migration generally, and to the sociopolitical and economic conditions specific to both Cuban and Venezuelan immigrants and parolees — conditions that have not improved in either country of origin. Against this backdrop of politicization, dehumanization, and uncertainty, this exhibition acts as a foil to prevailing media imagery of immigrants reduced to villains, victims, or collateral damage. Instead, it offers an immersive reclamation of memory and identity in all their fluidity and impermanence.

Vega’s phantasmagoric installation of mixed-media fabric sculptures and accompanying audio and projected animations, created in collaboration with Carlos Pedreáñez, melts reality and memory together. The forms resemble shrouded boulders and mountains at times, and dangling spirits at others, constantly mutating under projected drawings and photographs of relics from Vega’s childhood memories at her grandparents’ home in Venezuela. Looking upon the work, layers of brocade, tulle, and sequined fabrics fuse with nylon rope and a child’s old school uniform shirt. Vega relies primarily on recycled materials in her practice, and her process of sewing and weaving is largely intuitive. “When I’m weaving I feel like a spider … there’s no time, just me and the material … an ancestral connection,” Vega told Hyperallergic. That reference to ancestral connection is a nod to Indigenous Wayuu weaving practices and traditions; Vega further ties in her ancestry by including recorded audio of a poem she wrote, translated into Wayuunaiki, that plays with the projections like a spectral narrator.

The ever-changing experience of the projections illuminating the sculptures resembles the way that memories can shift over time and elicit a longing for the intangible, especially from a place of exile. Vega reflects on the authoritarian country she cannot return to while also considering the current climate in the United States: “I feel like I have déjà vu …. What’s happening in this circumstance feels like 1999 with [Hugo] Chávez,” she said, in reference to the former Venezuelan president’s consolidation of power mirroring recent American policy changes and shifts in attitudes, including increased policing and intimidation. “I feel fragile, I feel unsafe … I feel like an alien. I don’t want to feel like that.”

Across the hallway are works by Reynier Leyva Novo and Amalia Caputo. Novo’s “Solid Void” (2022–25) is a collection of 50 objects cast in white gypsum cement arranged on shelves. These items are at once familiar and unexpected, with some instantly recognizable — a margarita glass, a Solo cup, a juice pitcher — and others abstracted and unidentifiable. Each is the cast of a hollow vessel; the assemblage of the forms could pass for a cabinet of curiosities or a bookshelf in your neighbor’s home. “To remove them, we had to sacrifice most of the original objects. They are designed for endless emptiness — for being filled and emptied again and again,” Novo explains. “When you pour a solid into them, you violate that function. You cancel the everyday use, you cancel the rituals, you cancel the social and cultural processes attached to them. They stop being useful and become something else: pure shape.”

The stark white forms appear ghostly when seen at a distance against the black gallery wall, but up close, their mass becomes evident. The tension between form and function, and between presence and absence, makes each object feel like a metonym for a memory. Novo explains that the works are related to the experience of moving here from Cuba in 2021: “I had never experienced emptiness the way I did when I arrived here after leaving everything behind — studio, archives, books, routines, landscape. My own body felt like a container of immeasurable void. The piece is, in some way, a physicalization of that condition: a field of vessels whose interior is gone and yet somehow more present than before.”

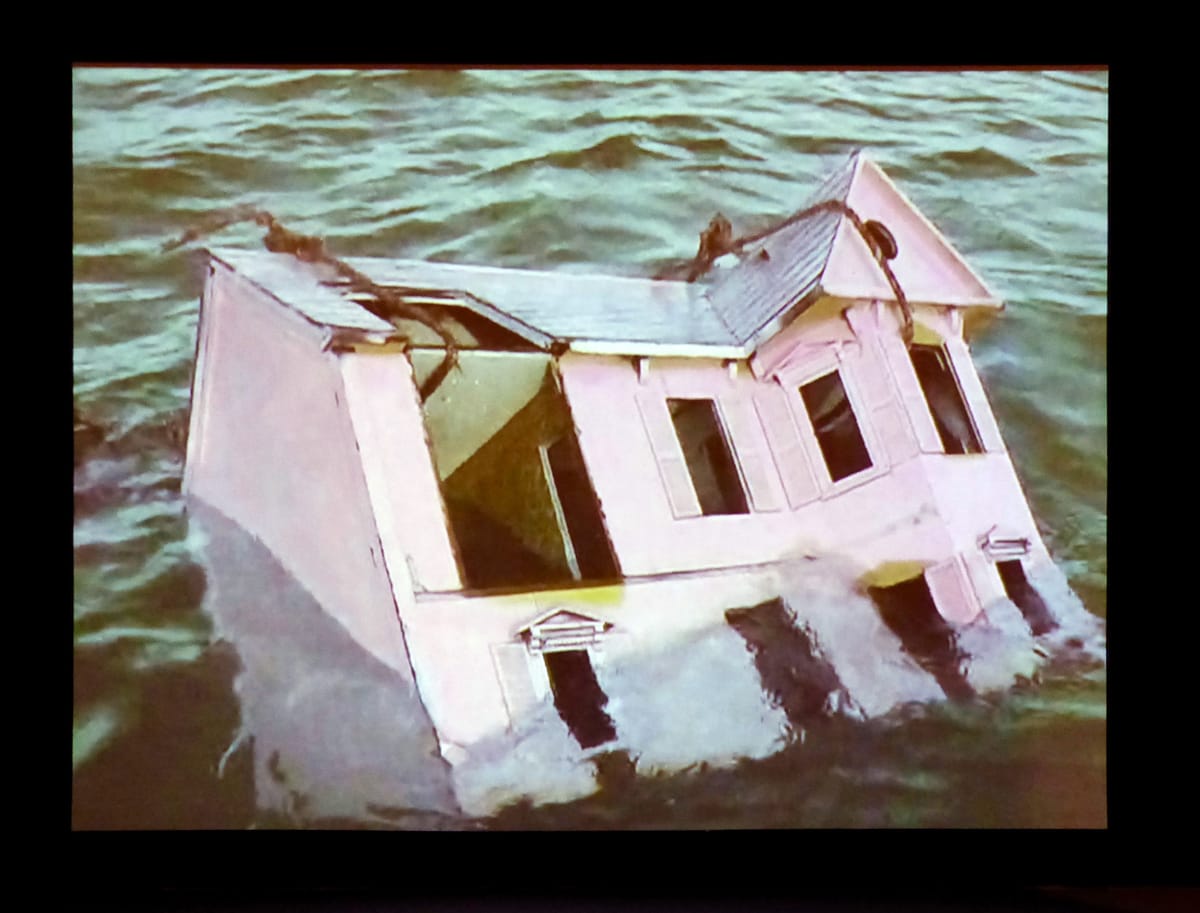

Directly opposite Novo’s work, Caputo’s video installation plays on a loop. The four-minute “La casa (de Hestia) [The House (of Hestia)]” (2010) depicts a woman dragging a dollhouse by ropes along a beach toward the water. The woman’s dress and the exterior of the dollhouse are a matching flamingo pink, a shade common to homes in the Caribbean. The title’s reference to Hestia, the Greek goddess of the hearth and home, coupled with stereotypical associations of femininity, brings the role of women as mothers and keepers of “home” in the process of migration into focus. Then, the dollhouse breaks apart across the sand, and the ropes ensnare the woman as she pulls the unwieldy house behind her. Caputo explains, “the transit, the woman carrying the weight of the home, the migration …. There’s a double message here dealing with womanhood and everything that grounds us as women … and about exile and migration.”

Seagulls squawk in the background, and random voices of beachgoers can be heard among the ebb and flow of the tide as the woman labors alone and in plain sight, recalling the ways life goes on as normal for much of the world, even those physically proximate to those experiencing migration or displacement. The video ends with parting shots of the house floating in the ocean by itself, without any clear resolution as to what happens to the woman. Together, Caputo and Novo’s works reflect on what we carry when leaving our home behind. As R. Delgado puts it, the connection between Venezuela and Cuba overrides the arbitrariness of human-made borders: “The Caribbean Sea is the thing that both unites us and separates us.” R. Delgado’s desire to “bend the frame” towards reflecting the dynamics of migration and memory fills a recent gap in institutional representation of Latine artists in the DMV, which is all the more urgent as escalating rhetoric and military activity in Venezuela and the Caribbean threaten to overshadow the experiences of people now living in precarity.

At its core, Tactics for Remembering deals with the inherent sacrifices that come with traversing borders to arrive somewhere new. “It’s about loss. It is about [what] we carry … and what we choose to keep when disaster hits,” R. Delgado says. “Suddenly, it's like everything that you think is so solid is actually super ephemeral. And the objects are here to help us maybe trigger those things before we forget them. We have a responsibility to continue our history.”