Wes Anderson Brings Joseph Cornell’s Studio to Life

The whimsical filmmaker recreated the Queens artist's home studio at Gagosian Gallery in Paris, the city Cornell longed for but never visited.

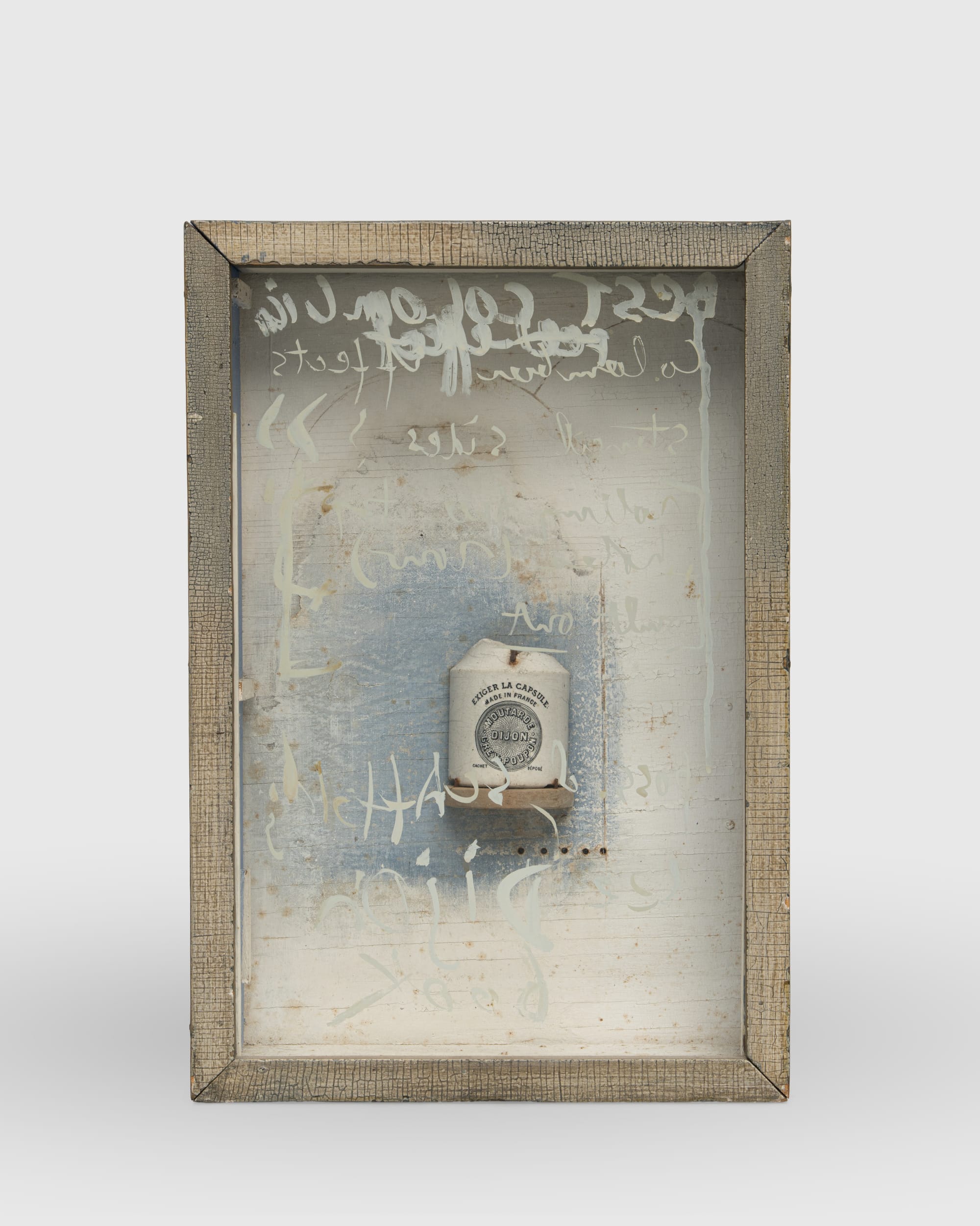

Even without any formal art background, Joseph Cornell was an expert collector and curator of found materials and curiosities. His influential shadow boxes, lovingly composed from mementos, curios, images clipped from their literature, and ordinary or ephemeral objects that he came across, became dimensional worlds of wonder that laid the foundations for assemblage and installation art.

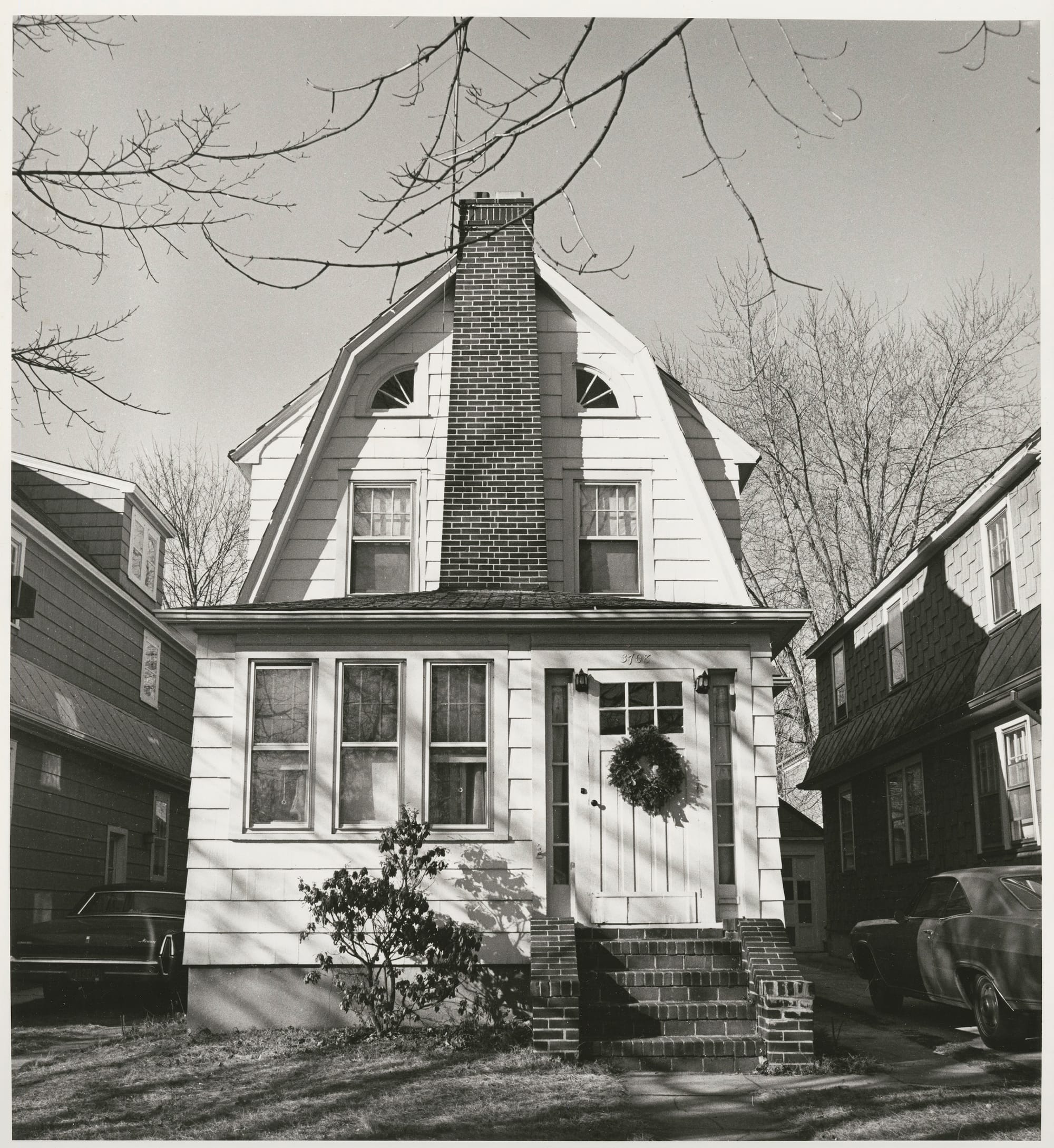

The source material of those worlds, squirreled away in storage boxes or stacked on nearly every surface in Cornell's basement studio at his home along Utopia Parkway in Queens, is reconvened in a new devotional exhibition that recreates the late artist's workspace. Gagosian curator Jasper Sharp and filmmaker Wes Anderson co-developed the exhibition at the gallery's storefront location in Paris, the city Cornell knew intimately and deeply longed for, but ultimately never visited.

“The location itself could not be more fitting: Paris was a place Cornell dreamed of his entire life,” Sharp said of The House on Utopia Parkway: Joseph Cornell’s Studio Re-Created by Wes Anderson, on view through March 14, in an essay about the show.

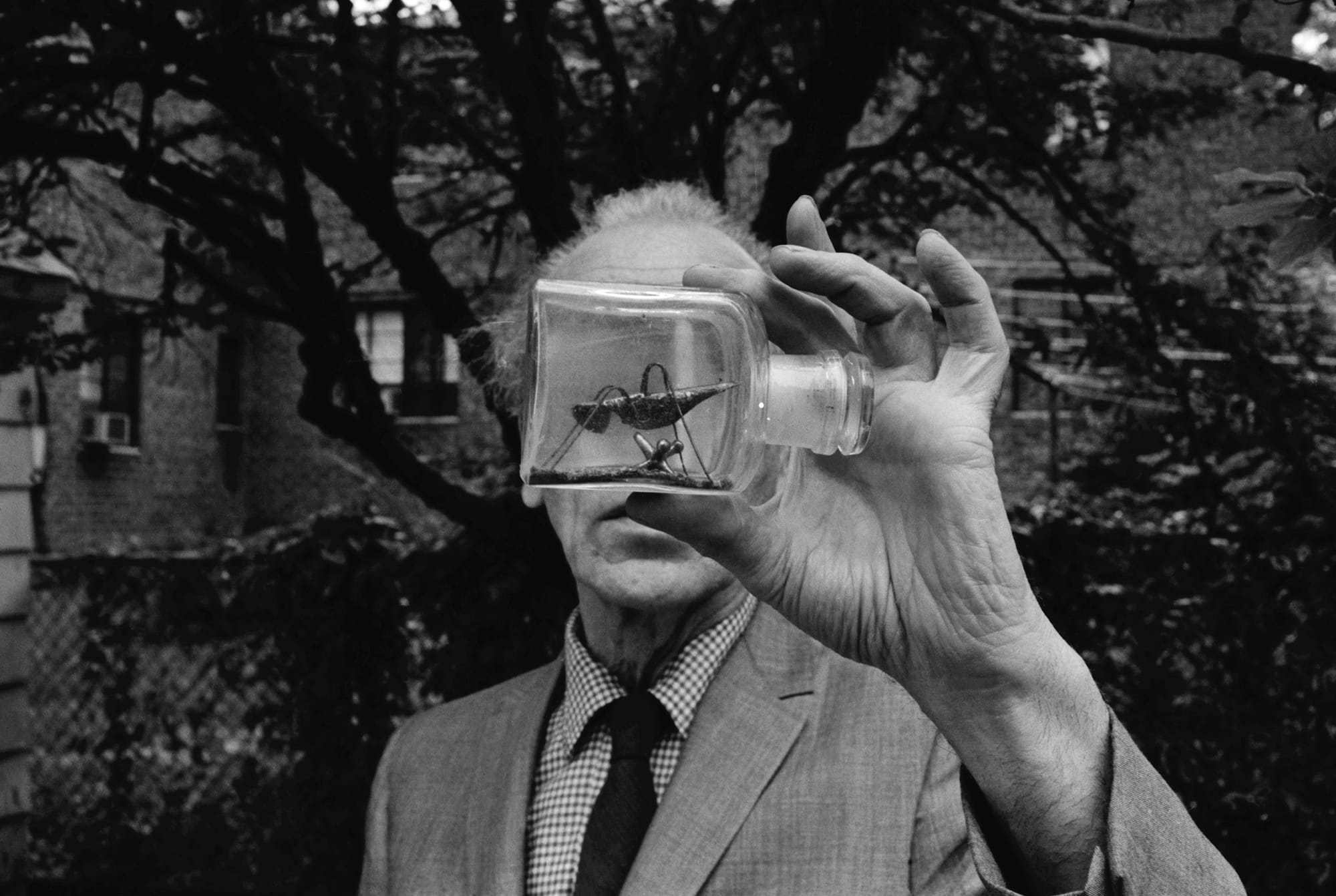

Sharp noted that during one of his first encounters with Marcel Duchamp, who would become a close friend of Cornell's, the pair had a long conversation about the city, highlighting landmarks such as the Louvre Museum and the historic Place de l’Opéra.

“Only at the end of the conversation did Cornell mention that he had never in fact visited the city, an admission that left Duchamp speechless,” Sharp wrote.

Works by Joseph Cornell, left to right: “Chambre Gothique 'Moutarde Dijon'” (1950) (photo courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery and Gagosian), “Untitled (Medici Series, Pinturicchio Boy)” (c. 1950) (photo by Owen Conway), “Pharmacy” (1943) (photo by Dominique Uldry)

Though many of Cornell's shadow boxes and collages live in institutional collections, the artist's sister gifted his collected source materials, letters and journals, library, and other personal effects to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in 1978, six years after he died. Now, through Anderson's fastidious eye and exhibition designer Cécile Degos's expertise, The House on Utopia Parkway has reunited some of Cornell's most noteworthy shadow boxes with his meticulously restaged studio filled with over 300 original objects he collected over his lifetime.

Works including “Pharmacy” (1943), “A Dressing Room for Gille” (1939), and “Flemish Princess” (c. 1950) physically command visitors' attention as they sit below eye level on scrappy wooden tables up front. In the background, dozens upon dozens of cardboard boxes labeled in Cornell's painted lettering are crammed into a ceiling-high bookshelf. At another corner of the studio below shelves of collected curios, inspirational ephemera are haphazardly strewn across a table equipped with a typewriter, wood glue, ink jars, and a painted wooden parrot, among other needful tools.

Cornell devoted many boxes to his loved ones, several artists he was friends with, and women he was deeply enthralled with. In an ultimate act of appreciation for the artist's practice, The House on Utopia Parkway itself becomes a shadow box, viewed only through the windows of Gagosian's softly lit storefront.

The exhibition is free to visit at Gagosian's rue de Castiglione location in the city's 1st arrondissement.

Left: Joseph Cornell’s studio in the basement of his family home in Queens, New York, 1971 (© Harry Roseman 1971) Right: An exterior view of The House on Utopia Parkway shows Joseph Cornell's completed work alongside his source materials. (photo by Thomas Lannes)