When Beauty Is a Draw and a Diversion

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones has discovered the benefits of unique stylization: objects and figures can be made in such a mannered way that they become visual metaphors, flexible in their vagueness.

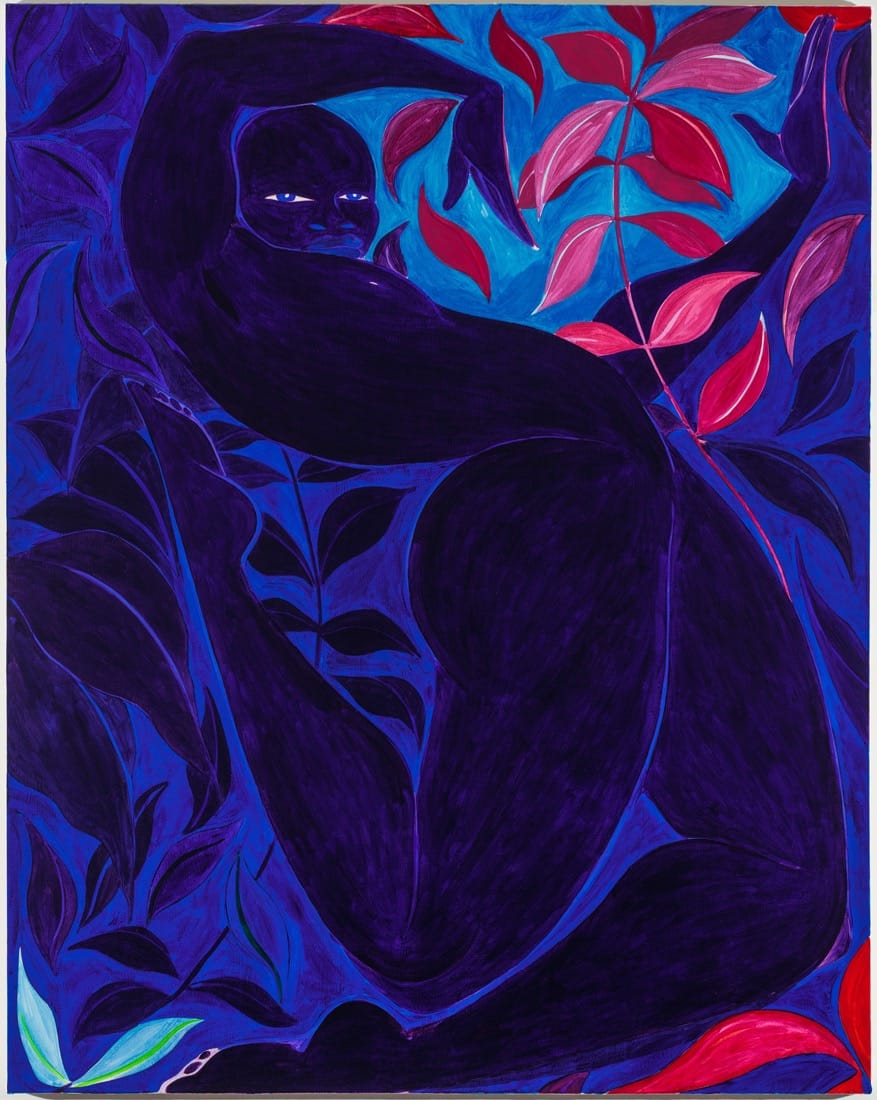

Most of the figures in Tunji Adeniyi-Jones’s exhibition at Nicelle Beauchene gallery seem shaped by the slow pull of a gravitational field that insists on everything assembling at its spiraling center; or, conversely, shaped by release from that field, in the process of resuming a more Euclidian form. Their thick, sloping thighs, curvilinear arms, cinched torsos, and tapered feet and hands are all stylized as if based on the template of a voluptuous falling leaf. Some of these leaves provide the backdrop for the foreshortened contexts in which the artist’s figures are placed. These foreshortened backgrounds, and the restricted palette of only two or three dominant colors in each piece — often hues of the primary pigmentation colors and primary additive colors for light, such as dark blue to deep indigo; the varied greens of foliage; or reds including tangerine and maroon — make these curvaceous figures feel like they come from fables.

Nichelle Beauchene released a press release for Flash of the Spirit that explains the figures as representations of “ancient royalty as well as deities of the Yoruba, called orisha.” But this seems only half possible. With his washy brush strokes Adeniyi-Jones has made figures that are so stylized they exist outside of time. Divine beings can do so (if you believe in Horus how possible is it to imagine a time when the god did not exist?), but aristocrats are typically defined by their historical contexts. Adeniyi-Jones has discovered the benefits of unique stylization: objects and figures can be made in such a mannered way that they become visual metaphors, flexible in their vagueness. Because they aren’t associated with any specific set of narratives, they also become figures which we can project into our own stories. Coincidentally, they also become representative of their maker. Here the figures attach to something that I can identify, that is the painter’s ambitions and his vision, such as with Matisse’s cutouts in the Jazz series. This all means that there isn’t much spirit for me to find here. There is lovely painting and ample fascinating style, and I’m left to wonder how far style can carry me and whether it will be to a worthwhile place.

Tunji Adeniyi-Jones’s exhibition for Flash of the Spirit continues at Nicelle Beauchene gallery (327 Broome Street, Lower East Side, Manhattan) through December 23.