What Do Classical Antiquities Look Like in Color?

Everyone knows that classical sculpture is white. Think of the gleaming marble of artworks like the Belvedere Torso and "Laocoön and His Sons" — the whiteness imparts a kind of purity, a sense of being the ground zero of Western culture, the original from which an entire civilization's canon has spr

Everyone knows that classical sculpture is white. Think of the gleaming marble of artworks like the Belvedere Torso and “Laocoön and His Sons” — the whiteness imparts a kind of purity, a sense of being the ground zero of Western culture, the original from which an entire civilization’s canon has sprung. Would we view these sculptures differently if they were in color?

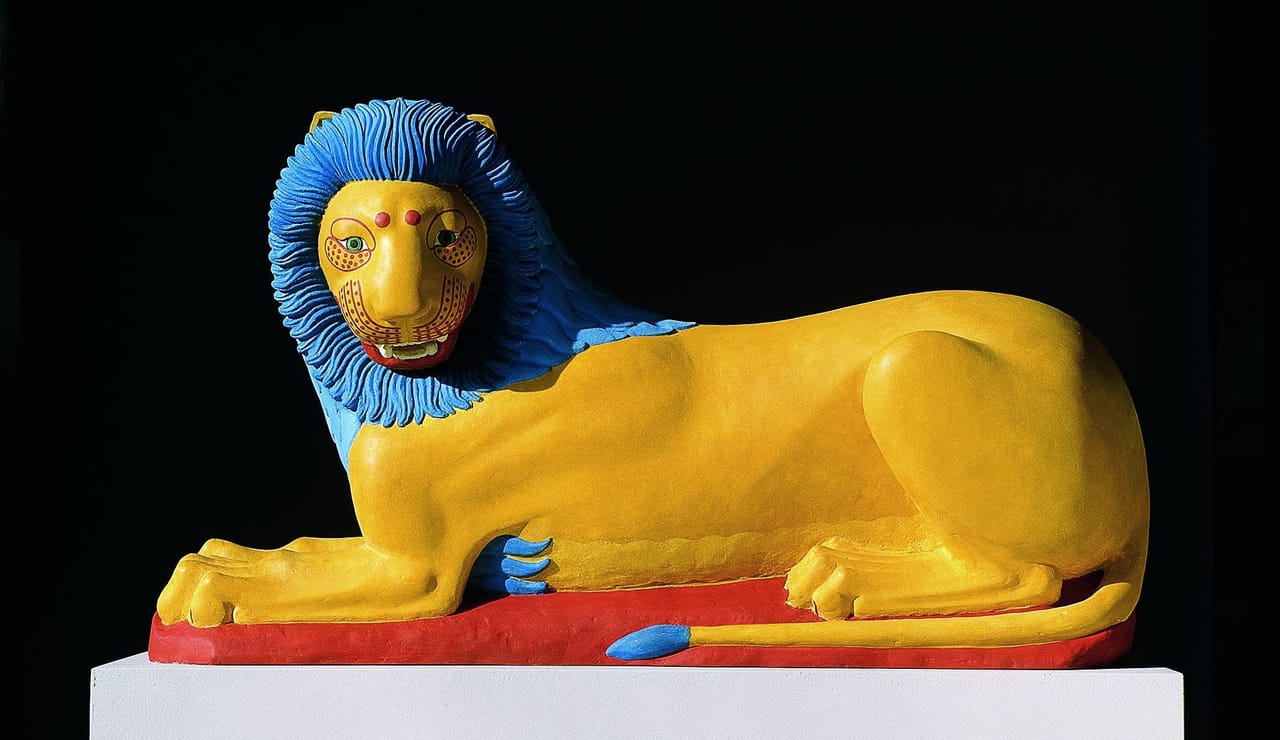

An exhibition currently on view at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen is making the case for polychromy. Transformations: Classical Sculpture in Colour argues that “Antiquity was anything but sceptical of colour” and that “the white marble of Antiquity was merely a tenacious myth.” The show features around 120 pieces: original sculptures alongside experimental, colored reconstructions.

Transformations grows out of the work of the Copenhagen Polychromy Network (CPN), an international and interdisciplinary research group that’s devoted to studying polychromy in ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. The network and its Tracking Colour project in turn were spurred by an initial exhibition examining polychromy at the Glyptotek in 2004. Ten years have passed since then, and considerable advances have been made.

“Research in ancient sculptural and architectural polychromy is an interdisciplinary venture combining the humanities and natural sciences. Technological developments in science are therefore affecting our field at an increasing rate,” CPN project coordinator and Transformations curator Jan Stubbe Østergaard told Hyperallergic over email. He continued:

The examples are many. Multi spectral imaging (MSI) is becoming an important means of identifying pigments; isotopic analysis allows provenancing of lead based pigments; X-ray diffraction spectroscopy (XRF) and other spectroscopic analyses are providing us with evermore refined information. The combined result is that the complexity of ancient sculptural polychromy and its interfaces with the sculptural forms is gradually reemerging. But we are still at the beginning.

Østergaard explained that the myth of monochromatic classical sculpture began during the Renaissance, when sculptures like the Belvedere Torso and Laocoön Group were discovered. “They were understood to be from classical antiquity, were therefore regarded as exemplary models — and they were perceived as being monochrome white, simply because their polychromy had largely disappeared over time. So, it was not a case of suppression, but of a misunderstanding by a small, highly cultivated and influential minority which was subsequently codified in art academies and transmitted on.”

He went on to add, however, that “suppression — and repression — may come into it when studying 20th century reception of the fact established in the course of the 19th century that ancient sculpture had demonstrably been polychrome: this fact collided frontally with long established European aesthetical, ethical, ideological norms, ultimately with Western identity.”

So, scholars have known for at least a century that classical sculpture was colorful, but that knowledge has not become common.

The Carlsberg exhibition may help change that. (Artist Francesco Vezzoli is also experimenting with the idea in his own but similar fashion at MoMA PS1, painting directly on marble busts.) But it’s admittedly a tough pill to swallow; looking at some of the before and after photos, what stands out (at least in this writer’s mind) is how … garish the color versions look, like a child might have painted the pigments on.

“The role of color in ancient sculpture is a decisive one,” Østergaard wrote. “It is decisive for the visual aesthetics of the sculpture, obviously; it is as clearly decisive for the legibility of a narrative in a variety of ways, from the painting in of sandal straps and horses reins to the blood oozing over the skin of a wounded Amazon, and on to the proper identification of subject of a sculpture — the Archaic Peplos Kore is not wearing a peplos and is therefore not a young girl (kore), but a goddess as evident from the dress parts shown only by way of painting.”

Indeed, even without understanding those details, the color does bring the artworks to life in a particular way. It seems to undermine that sense of timelessness we often attach to them, instead anchoring the pieces in a specific context. In doing so, it makes them more human and, ironically, brings them closer to us.

Transformations: Classical Sculpture in Color continues at Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek (Dantes Plads 7, Copenhagen) through December 7. For those who want to learn more, extensive information about objects and research methodology is available on the Tracking Colour website.