Wim Wenders Trains His Lens on a Photojournalist

Wim Wenders co-directed The Salt of the Earth, a portrait of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, with Salgado’s son, Juliano Ribeiro. The film is both a comprehensive portrait of Salgado’s work and a meditation on the vocation of photojournalism.

Wim Wenders has a unique ability to use documentary as a window onto other artistic mediums, whether they be music (Buena Vista Social Club), dance (Pina), or, in his latest film, photography. Wenders co-directed The Salt of the Earth, a portrait of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado, with Salgado’s son, Juliano Ribeiro. The film is both a comprehensive portrait of Salgado’s work and a meditation on the vocation of photojournalism.

Salt introduces general audiences to a broader selection of Salgado’s work than they have probably encountered before. New York viewers may be familiar with Genesis — exhibited at the International Center of Photography earlier this year — a series that portrays undeveloped parts of the world. The nature shots are astonishingly majestic in form and in scope; the series’ portrayal of indigenous communities, however, can feel uncomfortably idealized, seeming to promote an essentialized notion of primitivism. If Genesis were all one knew of Salgado, one might assume a certain photographic and moral philosophy. Salt shows that these suppositions would likely be incorrect.

As the film chronicles, Sebastião Salgado was born in Aimorés, Minas Gerais, Brazil, the son of a well-to-do farmer and the only boy among seven sisters. After an idyllic childhood in the midst of nature, he studied economics at university, and together with his wife, Lélia Wanick Salgado, became involved in leftist politics in 1960s Brazil. But under the rule of military dictatorship, Brazil was a dangerous place for leftists, and Sebastião and Lélia emigrated to Paris. Salgado first pursued a career in economics, but an increasing passion for photography and Lélia’s support persuaded him to change career plans. Lélia is clearly the unsung hero of Salgado’s career, and the film makes an effort to recognize her, both in brief interview clips and in Salgado’s narrative, recounting how her financial support and artistic assistance enabled Sebastião to take professional risks.

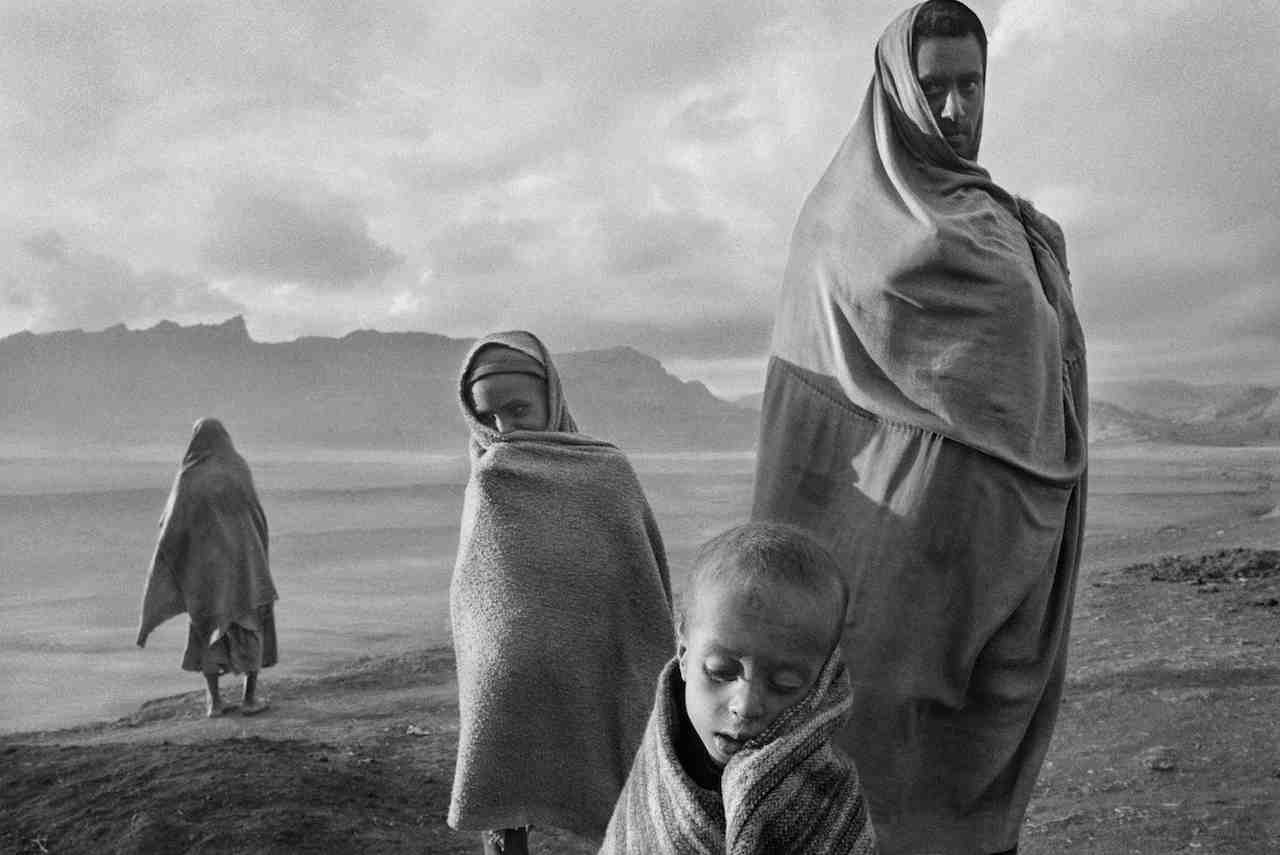

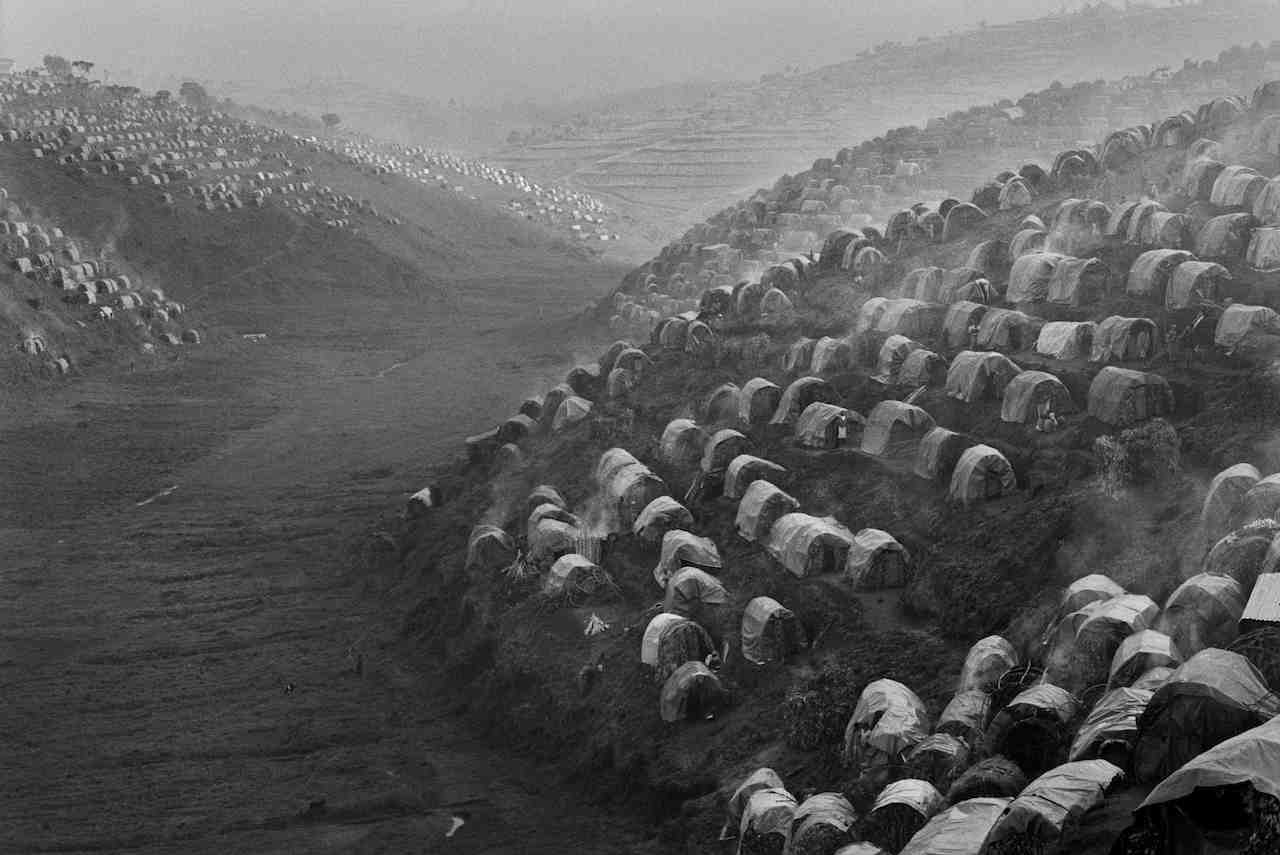

Salgado’s most powerful works are portrayals of human suffering. His 1984–85 series for Doctors Without Borders, Sahel, The End of the Road, is an extremely upsetting portrait of mass starvation due to drought; the images are as powerful a criticism of the allocation of global resources as can be imagined. And while shooting a series from 1994 to ’99 on displacement (Migrations), Salgado found himself on the edges of the Rwandan Genocide, chronicling waves of refugees. We learn that this experience left him questioning his role as photojournalist: no longer was he traveling the world documenting the ups and downs of humanity, but simply capturing the brutalities of man, total inhumanity. “We humans are terrible animals,” he says in Salt. “Our history is a history of wars. It’s an endless story, a tale of madness.”

This discussion of his crisis of faith and Salgado’s candid revelation of his and Lélia’s initial distress when their second son was born with Down syndrome are the most personal moments in the film. Salgado does reveals his feelings, but most often through empathy with his subjects. To refocus the film, Wenders borrows a bit of Werner Herzog’s signature style and narrates as a disembodied voice, occasionally sharing the role with Ribeiro Salgado. These voiceovers work well, adding elements of the personal relationships between filmmakers and protagonist, thereby keeping Salt focused on Salgado the man, not solely Salgado the photographer. The film is largely structured chronologically, as Salgado reflects on his career; still photographs are given substantial screen time. Salt is therefore driven primarily by Sebastião’s voice, although also shaped by Wenders’s and Ribeiro Salgado’s.

According to the film, Salgado was saved from his depression after Migrations by returning to his childhood farm in the late 1990s, and by a subsequent refocus on nature instead of man. At the time of Salgado’s father’s death, the farm was in a bad state; the once lush surrounding forest had been decimated. Lélia suggested they replant it. After trial and error, they succeeded, and now the land has become the Instituto Terra — 17,000 acres of successful reforestation.

Salt is most profoundly about what it means to be a documentary photographer, a witness to the world. The film also ponders where the wise, having seen both beauty and horror, might place their faith. Salgado has placed his in nature, not in mankind. One senses that Wenders and Ribeiro Salgado were as moved by the photographer’s now quiet philosophy of identification with the cycles of the earth as viewers are sure to be.

The Salt of the Earth is currently playing at select theaters in Los Angeles and New York City, and opens at more theaters nationwide in the coming months. See the website for details. Sebastião Salgado’s work is also currently on view at Sundaram Tagore Gallery (547 W 27th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through May 16.