The Virtual Is Liminal: An Interview with Claudia Hart

I first met Claudia Hart in 1995, when she was living in Berlin and I had gone there to do research for a project.

I first met Claudia Hart in 1995, when she was living in Berlin and I had gone there to do research for a project. A short time after she returned to New York in 1996, we became reacquainted — I think both our professional relationship and our friendship grew out of shared intellectual concerns. Even though our work is realized by quite different means, we both care deeply about content and think about the female body, decay, and historical time.

Claudia entered the world of 3D simulations technology at a time when there were very few practitioners who saw it as a means to create what I would term “fine art.” In addition to being an important innovator in the field, she has worked as a member of the faculty of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, teaching and influencing a remarkable cohort of students that has emerged from her classroom to make significant contributions to this new medium. She has helped take a technology that, until recently, was being used primarily for gaming and commercial purposes and subvert its form and content to create hybrid works that are genuinely new — and feminist, to boot.

This interview was conducted on the occasion of her solo exhibition at Transfer gallery, which was founded by Kelani Nichole in 2013 and focuses almost entirely on new-media work. The exhibition, titled The Dolls House, runs through July 2.

* * *

Claudia Hart, “Caress” (2011)

Susan Silas: I wanted to begin with a very general question. We know that many of the technologies that govern the internet and new-media applications had their origins in government research and were often intended for use by the military. Forms of these technologies made their way into gaming, which has been dominated by men both as creators and as users and has evolved into a relatively misogynist environment online. When you decided to learn 3D technology 20 years ago, did you understand that the environment was such a masculinist one, and were you thinking about usurping it then for a more feminist project? Or did your project evolve slowly as you began to work with this new technology?

Claudia Hart: In terms of simulations technology, which is my medium, yes, it emerged from the Department of Defense (DoD), and the culture around it was militaristic and astonishingly misogynist. I did not understand that it would be like that and had never experienced that kind of culture. The DoD had developed it for war games and flight simulators. When 9/11 came along, they strategically threw their research to the game industry, relatively small at that time; Pixar and children’s animation was a way bigger industry. But with 9/11, the military shared information with the game industry because they understood that the technology could be expanded there more rapidly.

War games were being produced both by the military and also commercially to cultivate a “war on terror” culture. I could not have predicted the sea change that would occur due to 9/11 when I started in 1997. My reasons for falling in love with computer imaging were purely artistic and theoretical, and had nothing to do with the positioning of virtual media and simulations technologies as both a commercial and military visualization language.

I was astonished and, yes, frightened, when a prize-winning 3D artist at the esteemed Ars Electronica media festival in Linz won with an image of a half-naked woman clamped to a motorcycle with the tail pipe emerging from her anus.

SS: One of the first works of yours I saw after you began to work with 3D technology was a single-channel piece titled “Machina.” The image showed a reclining nude, presented in the manner of a classical painting. Her movements were quite slow, her body languid and also voluptuous — not the hard body of contemporary culture nor that of a cartoon character with a tail pipe up her anus. In any case, she was framed to suggest a painting, and her body type was somewhat Rubenesque, yet she had something in common with Manet’s “Olympia” too, in that she made eye contact with the viewer from time to time, a kind of Brechtian device that disrupted the objectification that we associate with female nudes in painting. At that time, it seemed to me, most 3D art (though not all) was engaged in a self-reflexive investigation of the technology, which produced more formal and abstract visual content. How was your work received at the time? Did you get support from others working with the technology?

CH: My involvement with the digital art community began when I visited Ars Electronica with Kurt Hentschlager, the pioneering Austrian media artist who at that time was part of the duo Granular Synthesis. He has since become my husband and has a significant impact on my work. This was in 1995, and it was and still is the premiere venue for experimental digital media art, the festival that awarded the motorcycle babe a prize (I think that genre emerges from the male and misogynist culture of West Coast comix). Most of the more serious artistic work at Ars — aside from that of Granular Synthesis — was very formalistic and, yes, “gadgety,” meaning more concerned with technical invention and research and the visual possibilities that might be engendered for those.

When I was a young artist, my community was the 1990s identity politics generation. We were very content driven in the sense that the strategy was to deconstruct both media and material culture. I was obviously an interloper in that first generation of digital artists.

I actually got no interest and no support from that first and formalistic generation of digital artists. Their work was procedural, meaning driven by algorithms and systems that generated abstract patterns. Mine was feminist, psychological, and expressive, and at base driven by a kind of dialectical mind/body conflict. I wanted my audience to feel their responses, not just think them. My art is phenomenological.

Since then, digital culture has changed, and younger media artists share my orientation. This is the generation that is sometimes called “postinternet,” many of whom are former students. I’ve been very involved in developing a language around its terms. Significantly, there is a serious feminist component to this culture, both activist and supportive, which I think is a very important contribution of this generation. It’s actually opened up my world, and I’m exceedingly appreciative of this!

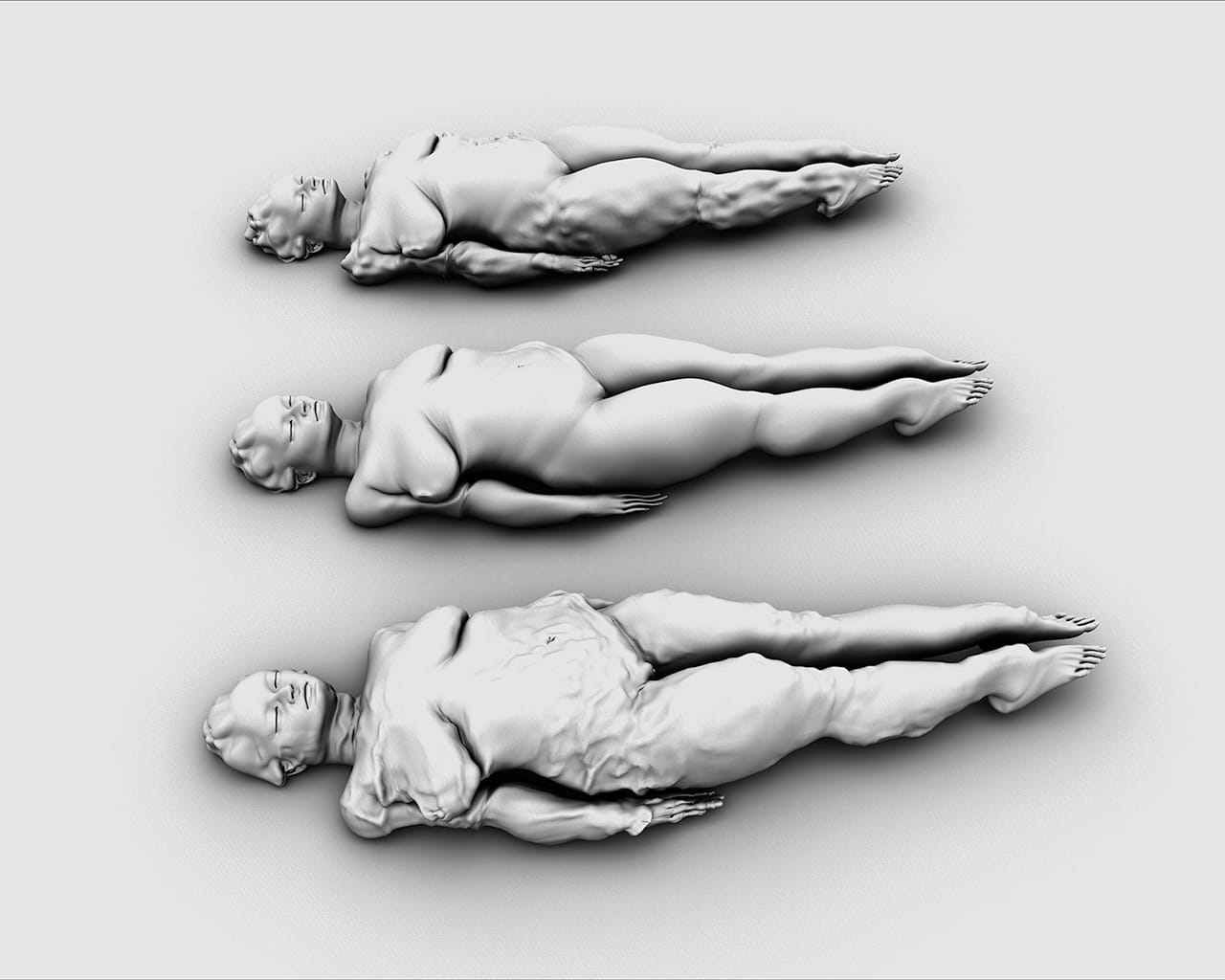

SS: After “Machina,” you made several other works — “The Swing” (2006), “Mortifications” (2007–11), “Ophelia” (2008), “The Seasons” (2009) — that represent the female body as fleshy or zaftig. It’s a curious choice given that a Rubenesque form seems so remote from the bodies we often see representing robots, cyborgs, avatars, etc., which all seem to be modeled on some sort of hyper-Barbie. Can you talk more specifically about this choice? It’s a type we are more familiar with from 19th-century painting.

CH: I wasn’t thinking about 19th-century painting but certainly about classical figure painting in which women are eroticized. “The Swing” was inspired by a painting of the same name by Fragonard. With “Ophelia,” I was thinking about the 19th century, specifically the Pre-Raphaelite painting of the same name by John Everett Mills. “The Mortifications” sculptures were, to me, some kind of mutation of Baroque sculpture by Bernini, and in fact, the first “Mortification” was actually modeled on the 1983 movie Flashdance! So it was my version of Saint Theresa meets Jennifer Beals’s erotic dancing in a strip club.

I tried to invert everything associated with the 3D animation I’d seen, from Pixar children’s entertainments to first-person shooter games. I wanted to inhabit male painters’ territory, to be a woman who could now define feminine erotica and sensuality, and to use the language of a certain kind of high art, one that was hyper-decorative and pretty. All of these approaches were “outlawed” in the gaming world, and also outlawed in the digital art world at that time. It was, however, a strategy embraced by my generation, the identity politics group from the early ’90s.

The first model I built, the one that was the woman I used in “Machina,” the beginning of the body series that you saw in 2004, was inspired by Raphael and Titian odalisques. She was not designed after me but rather after my mother: an ordinary, imperfect woman who appreciated her body and was not ashamed of it.

I also imagined that I was constructing a time-based painting that was a model of mind, of what happened inside one’s mind when one contemplated a painting. So, if a painting had mind time inside of it, I imagined it as being very slow — not obeying the laws of either the real world or of cinema. The time inside of a painting would not be linear, would not proceed from beginning to end, but would rather be elastic, circular, self-referential, and self-reflective. Like a computer, my painting time would be a system that was reflexive: a system that uses itself to build itself.

SS: You have somehow anticipated my next question. I saw a short video interview with Tacita Dean in which she talks about “film time” as something she understands to be specific to her medium. In some of the other works you’ve made, you engage time as subject matter. I’m thinking specifically of the two versions of “Timegarden” (2004, 2005) and of “Noh-timeGarden” (2007) and “Empire” (2010). Can you talk about how digital time might differ from film time? These works engage time differently, it seems to me, than “Machina.” Do you also see these as circular and self-reflexive?

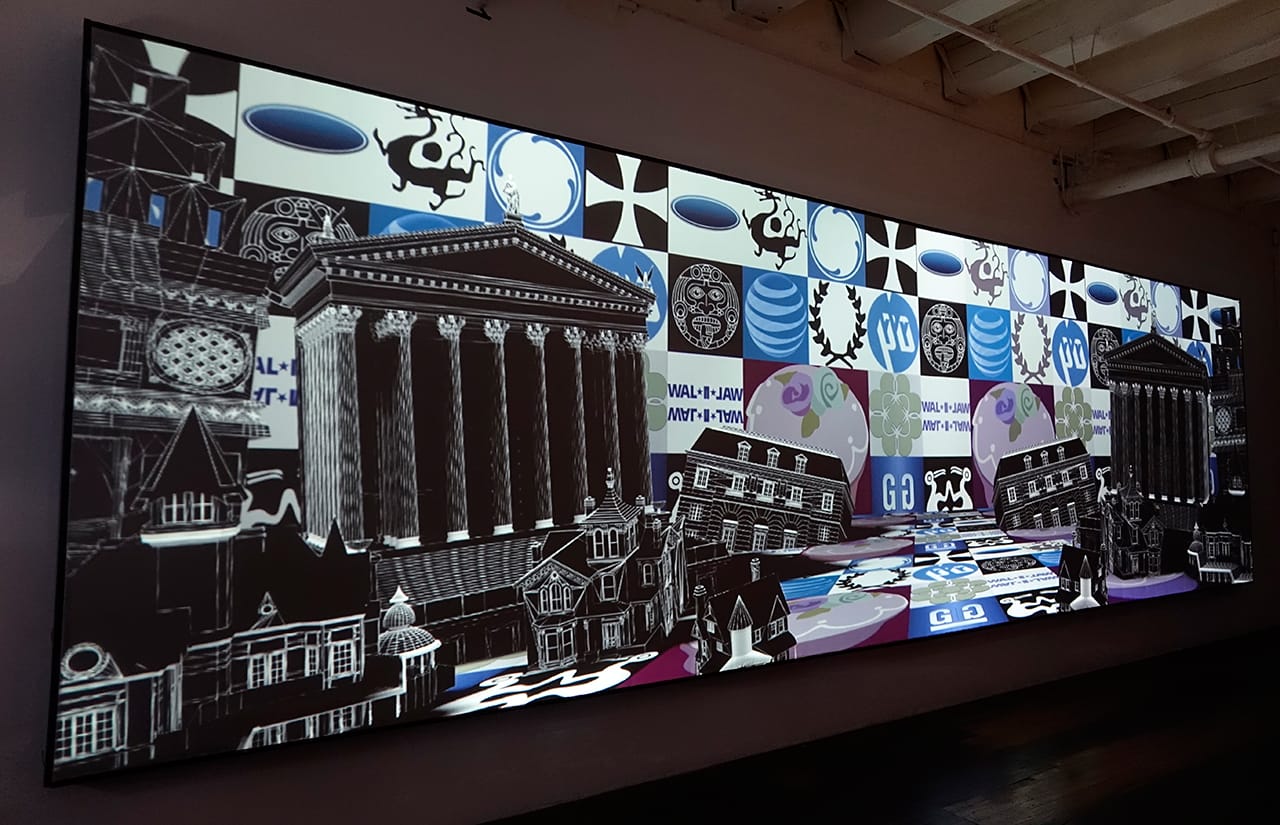

Claudia Hart, “Empire” (2010)

CH: Works like the “Time-Gardens” and particularly “Empire” are about the dialectical process of history, which is another cyclical idea, as I also imagined perception as nonlinear. I’m a Nietzschean, meaning I think of death and decay as creative agencies that engender rebirth. “Empire” was inspired by The Course of Empire, an 1836 series of paintings by the Hudson River School artist Thomas Cole imaging the course of Western history. I also looked at drawings by Étienne-Louis Boullée, the 18th-century French visionary architect whose cemetery designs for an “ideal” city presaged modern architecture.

In my version, women are the architectural piers of an almost endlessly long building, four screens wide, whose bodies slowly age, decaying over a period of time, while synthetic ivy grows over them. I timed them so that the unfolding of the animation would occur at the edge of perception, so it would seem like nothing was happening. The lighting of this virtual set moved from sunrise to sunset, from black to black, so that the film looped. When I made it, I thought perhaps it was too boring, and the audience at the Wood Street Galleries, who commissioned it, confirmed this. I remember listening to their comments at the opening as they complained about it. I recently rescreened “Empire” for the first time since I showed it in the Pittsburgh installation, at the Gene Siskel Theater in Chicago. Six years later, it seems very activated. But of course, I’m also physically older, so time passes more quickly for me now. It’s all perceptual. That’s the point!

SS: Are these works constructed out of code, and if so, how do your imagination and your notion of nonlinear time evolve from binary code, which I thought was linear?

CH: I think you are bringing up several important issues with this question. I don’t think that the binary nature of code, meaning its yes/no aspect, is any more or less reductive than the letters in any alphabet’s notating language. What I can do with it is express a kind of nonlinear, unpredictable sense of time by using my various virtual-reality (VR) softwares. In VR software, you graphically build models like an architect does. Virtual models exist in time, however, and can proceed unpredictably in that one can exert simulations of natural forces onto them. These forces can only be processed in relation to a timeline — in my case, one playing back at 30 frames a second, the play rate of animation. My kind of VR software is related to those used in flight simulation or weather prediction. One can exert computer simulations of physical forces — say, “turbulence” or a “vortex” or “noise (chaos)” — onto computer objects that are otherwise inanimate, and those forces “animate” them.

For example, in “Dark Knight” (2011), an animation of an avatar trying to break out of the virtual world into the real one, I rigged a human model with a simulated human skeleton and then simulated shaking it violently in a box. I imaged one side of the box to be the monitor screen. I also dropped the avatar down a long shaft, batting it from side to side with a simulation of wind. I bounced it like a yo-yo against a wall. I had no idea what would happen when I did any of these things, but I knew it would be brutal, because, well, wouldn’t that be? And then, because I simulated natural forces, the recording I made of it had an uncanny realism to it, despite the fact that the style of representation is not photorealistic.

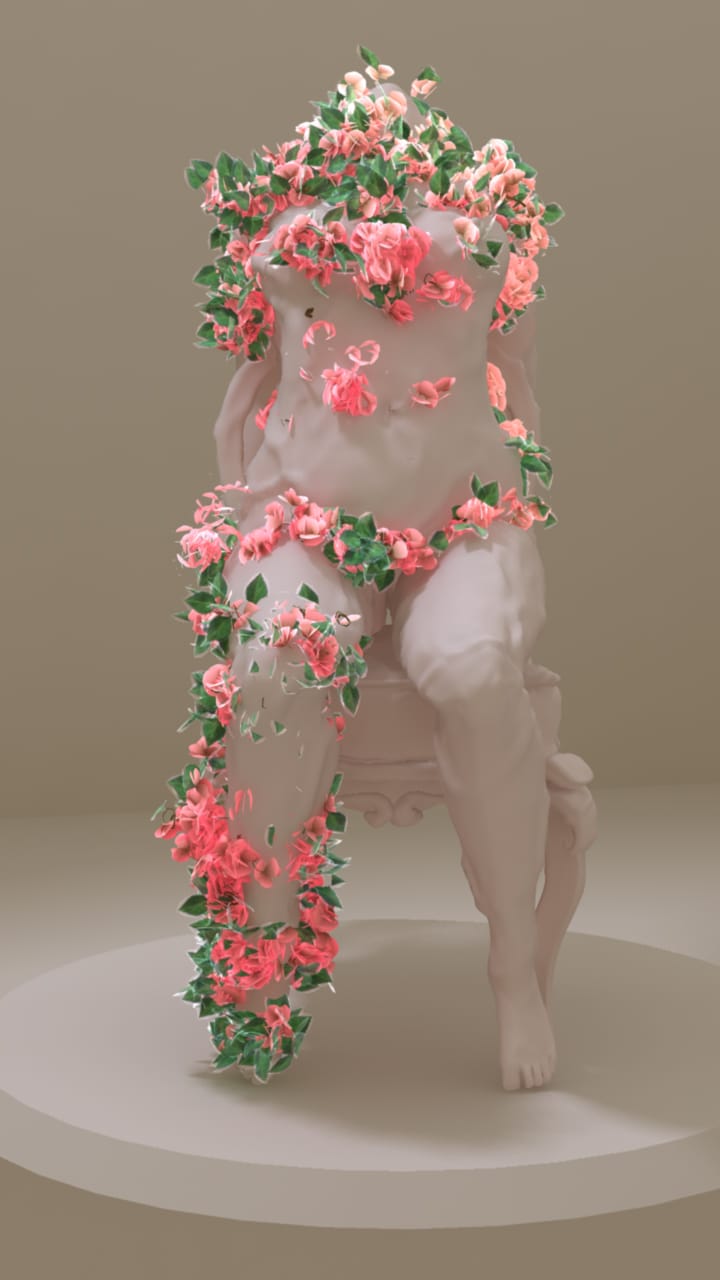

My projects are like science experiments. I always show the results as is and refuse to fix them, as if they were documentaries unfolding in reality. Another example is “The Seasons” (2007), where I used a function simulating the growth of roses. There was actually no function for “dying” roses in the software, so instead I “inverted” growth, meaning I used negative numbers to calculate it rather than positive ones. What happened was that, rather than wilting, the roses exploded at a certain point, dissolving into dust. I’d unexpectedly created a strange kind of computer death, recorded in a hypothetical “real” time.

These kind of works fake the unpredictability of life, yet make it very strange: both familiar and alien at the same time. It makes the events they record seem somehow dead, because my avatars resemble designed objects, not flesh or organic, that nevertheless behave in irregular ways rather than mechanistic, predictable ones. Computer programmers simulate such natural forces by designing in randomness, as exists in natural life. So simulated beings seem uncannily alive. When I brutalize them, their sad, pained facial expressions become a real condemnation of the brutality of shooter-game and effects-film culture. At the same time, they are a very poignant elegy on the process of time and the biologically inevitable march towards death.

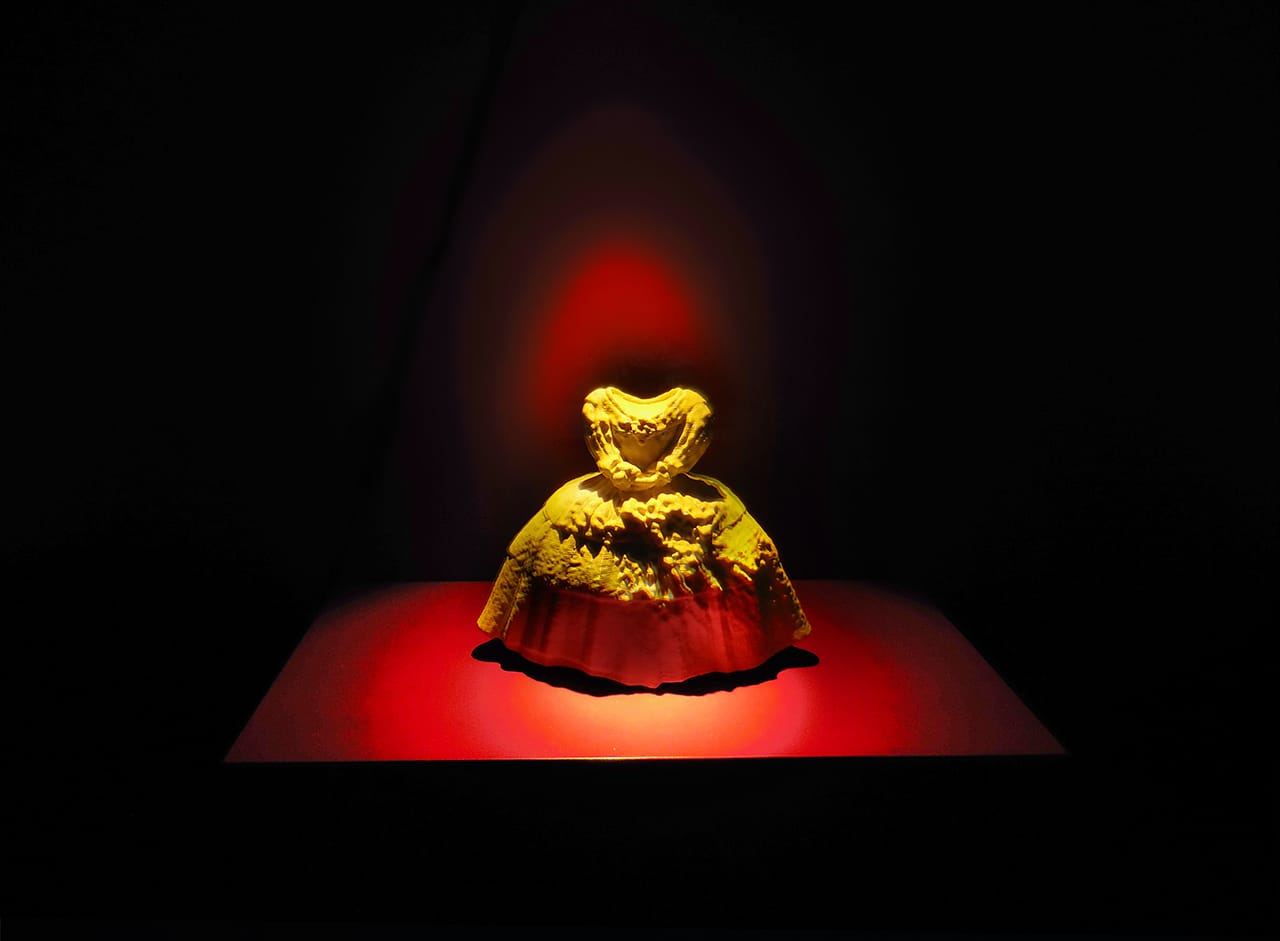

Claudia Hart, “The Dolls” (2015)

SS: This seems to be related to your most recent theatrical works. In “The Alices” (2013), “Alices Walking” (2014), and “The Dolls” (2015), a ballet, your performers engage with unpredictable scenarios because they use interactive technologies live on stage. In the case of “Alices Walking,” there was a real-time, interactive musical score and a real-time video projection of what was transpiring onstage. In “The Dolls,” you projected animation onto dancers’ tutus, and the dancers’ motions triggered changes in the projected set. Do you feel that those interactive elements took place in a different space/time than what was happening on the stage? You seem to be particularly concerned with the membrane that separates the actors from the audience and endows all theatrical space with a hyperreal quality.

CH: Software in general is interactive, as much as the custom interactive tools I use in my theatrical performances. When my performers use them, they embody the human–machine interface — a spin on the idea of a cyborg. Interactivity is also a permeable membrane, like the proscenium of traditional theater, functioning as a connective space between a human and something artificial. These are all “machines” of sorts, giving the machine humanistic qualities and a human, mechanistic ones. But while software generally makes humans smarter, interactive hardware, like the one composer and software designer Ed Campion developed for our collaborative opera, “Alices Walking,” is way more limited. Rather than making the humans using it smarter, it actually makes them appear dumber, akin to Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times.

In my version of Alice in Wonderland, five cloned Alices were controlled by audio signals run by Ed, pulsating in earphones. In the “Alice” system, machines controlled humans, rather than the other way around. The idea was to turn the Alices into automatons, and it worked! At the same time, unrehearsed and live onstage, my Alices were pursued by a select group of audience members, personally invited to watch from tiny children’s chairs arranged around the stage. This group was also given digital tablets with custom Alice in Wonderland augmented-reality software loaded onto them. The app allowed them to see “magical” illusions embedded in “The Alices”: animations precisely mapped onto their costumes. “The Alices” were covered with phantasmagoria that the rest of the audience, offstage, could not see. I also streamed the onstage actions as live video into the theater space (Eyebeam) and distributed binoculars. This setup resulted in a kind of hysteria, not planned for. The audience refused to stay in their baby chairs and chased the Alices around the stage, trying to catch a glimpse of the augmented illusions through their tablet cameras. They were like crazed paparazzi, chasing their superstars. Totally nuts.

When you look at the world through an augmented app, you can see animation and media seamlessly integrated into the material world. Augmented reality is a strange brew, mixing the real and the phantasmagoric into one. It’s exceedingly seductive and seems to promise that one’s dreams can come true. It also turns the entire audience into Peeping Toms or paparazzi chasing their prey. It was like a big, dysfunctional Rube Goldberg machine. It was both absurdist and scary, a dystopian vision of evil machines controlling human spontaneity.

“The Dolls” played more with the hypnotic possibilities of recursive feedback and wave-like repeating patterns. We used motion-tracking software, which is at this time not very robust. I projected video onto paper tutus worn by dancers, so the only kind of movement that can be tracked is very limited, robotic and restrained. Kristina Isabelle, the choreographer that I worked with on this project, was constantly frustrated by these limits. The dancers were then also tracked and mirrored, repeated and fed back as a live video stream projected onto the set. At the basis of these patterns was a mixture of US corporate logos and the heraldry of collapsed empires: Rome, the kingdoms of Louis XIV and the Hapsburgs. The end result was an environment expressing the flow of my own process — a life lived, for the most part, in a virtual environment.

All of my works represent the kind of fluid world that is enacted in the theater pieces. To me, the virtual is compelling because it mixes the artificial with an unpredictable sense of the real. I relate it to what anthropologists of religion call a liminal state. This is a state on the threshold, before a participant experiences a promised transformation. I think that VR media and mediated theater are highly charged liminal environments. In them, we feel both real and not real at the same time. In all of my work, I collapse opposites: body and trace, body and ghost, body and mind. In a liminal state we can be alive but also not. We can embody mythological, disembodied beings existing both inside and outside of time. Such experiences make us feel that we might live forever, that we have solved the death problem! And even if only for a moment, what could be better?

Claudia Hart: The Dolls House continues at Transfer (1030 Metropolitan Avenue, East Williamsburg, Brooklyn) through July 2.