Destroy the Brutalism, Leave the Picasso: A Debate Over What's Worth Saving in Oslo

After being damaged by a 2011 car bomb, some Brutalist architecture in Oslo is up for demolition. While the debate between the protection of Brutalist architecture and those who see its heavy concrete designs as ugly and bleak is not infrequent in preservation, these buildings include five murals by

After being damaged by a 2011 car bomb, some Brutalist architecture in Oslo is up for demolition. While the debate between the protection of Brutalist architecture and those who see its heavy concrete designs as ugly and bleak is not infrequent in preservation, these buildings include five murals by Pablo Picasso.

As Architizer reports, the major point of contention is that the murals in the Regjeringskvartalet government center were meant to be part of the structures designed by Norwegian architect Erling Viksjø, and preserving their integrity means preserving them with the building. On July 22, 2011, a car bomb exploded in front of the H-block building at the complex, killing eight and injuring 209, and was followed by an attack by a gunman at an island summer camp where 69 people were shot.

The Regjeringskvartalet sustained significant damage, yet structurally it was sound, and the murals on the H and Y block were safe. However, as part of the physical and emotional rebuild, the government proposed that the buildings be destroyed for more modern designs. The debate has escalated as different proposals are being looked at this summer. A July editorial in the Dagsavisen newspaper asserted that the proposal for demolition doesn’t just overlook the importance of the murals in their intended place, but disregards the importance of Viksjø’s monumental design and his interpreting of the ideas of Le Corbusier and the reactionary embrace of modernism post-WWII. A bit more fuel has been thrown in by the National Museum in Oslo, which opened an exhibition in June called Picasso — Oslo. Art and Architecture in the Government Buildings. The museum doesn’t waver on words, stating in their text that “the art decorations in natural concrete were novel, radical, and sensational at the time, and the architecture and artwork are intimately and indivisibly connected.” According to the BBC, a poll by the newspaper Verdens Gang shows 39.5% in favor of demolition and 34.3% against (no details on what the rest of the polled favored).

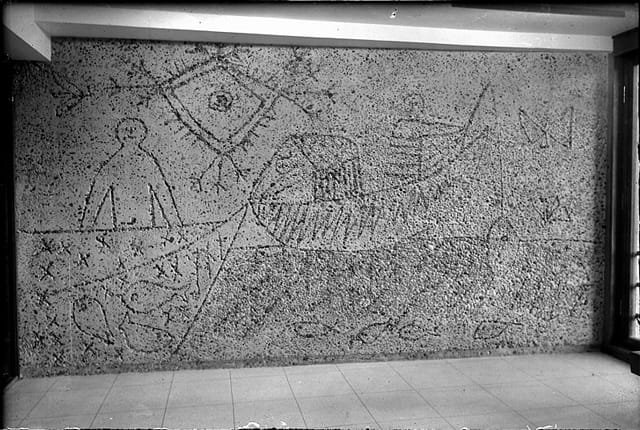

The murals, created between the 1950s and 70s, were Picasso’s first work in concrete with Norwegian artist Carl Nesjar, with whom he would create over 20 pieces in his lifetime, such as the “Sylvette” sculpture between the I.M. Pei Silver Towers in New York. Nesjar had a new concrete process for these “betograves” that involved sand blasting to reveal dark stones within the concrete, and after Picasso sketched the designs for Oslo, Nesjar blasted them into place for the concrete construction.

The architectural heritage of Brutalism has been a hard one to preserve. The Gettysburg Cyclorama by Richard Neutra fell this March to the cheers of a crowd, the demolition of the spacey Prentice Women’s Hospital by Bertrand Goldberg in Chicago started in June, the Orange County Government Center by Paul Rudolph was saved at the last minute, but is still in danger of destruction. It doesn’t help that architect Erling Viksjø is not much known outside of his native Norway, and even there his buildings, like the Bakkehaugen kirke and Tromsøbrua bridge, are seen as foreboding and cold. Artist Dag Hol crowed last month in Aftenposten newspaper that now is a prime chance to rid Oslo of this “brutal, ugly and degrading architecture.”

The Picasso murals aren’t themselves in danger of being destroyed; if the building goes they’ll likely be taken apart in segments and resurrected elsewhere. But the building has less of a chance. As Joern Holme, the head of the Directorate for Cultural Heritage, rightly stated: “We can’t demolish the best [parts] of a cultural era just because we find it ugly today.” Yet too often that’s what happens with Brutalism, that widely unloved of modernist concrete architecture, where the favoritism of form over the conventions of traditional beauty doomed it to future loathing.