The Geodesic Dome Dreams of Quebec

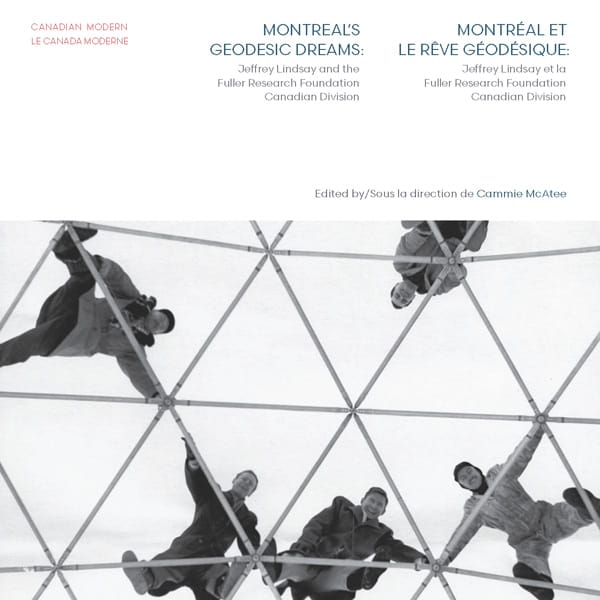

In the 1950s, architect Jeffrey Lindsay led a little-known era of geodesic dome design in Québec, which is explored in the new book Montréal's Geodesic Dreams.

“I think there’s something very hopeful about the dome,” architectural historian Cammie McAtee told Hyperallergic. McAtee authored Montréal’s Geodesic Dreams, out now from Dalhousie Architectural Press, and curated an exhibition of the same name that was recently on view at the University of Québec at Montréal (UQAM) Center of Design. The geodesic dome is still associated with a postwar era of optimism, when World’s Fairs like the one in Montréal in 1967 promised a space-age future where architecture and design could shape a better quality of life. While American architect R. Buckminster Fuller is the big name in popularizing geodesic domes, envisioning them as a solution to affordable housing and even living in an example himself, it was a Canadian man named Jeffrey Lindsay who in 1950 realized the first self-supporting, large-span geodesic dome.

“After the war, Canada didn’t have the same rations on materials as the US, and there were possibilities here with the aluminum industry that was booming in Québec,” McAtee explained. Lindsay was one of Fuller’s first students, taking a 1948 seminar at the Chicago Institute of Design and subsequently studying with him at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Lindsay then founded and directed the Fuller Research Foundation Canadian Division. “Fuller gave his students in that first class a ‘Dymaxion License,’ where they were all given the right to use these ideas,” McAtee said.

A geodesic dome has an incredibly strong structure through its triangular shapes, all based on a geodesic polyhedron. This means they can be lightweight and use materials economically, especially compared to a walled building of similar size. McAtee first learned of Lindsay’s contributions to dome history when she received a call in 2011 from a local architect about a geodesic barn that was about to be demolished. She drove out to see it before it was torn down. Over the years its plastic covering had failed, so it was covered with tin, yet the shape of the dome was there.

“Unfortunately, we weren’t able to do anything to save it, but in finding it, we found out who the designer was,” McAtee said. And in turn, she discovered that Lindsay’s archive survived with his widow in Palm Springs, California. Lindsay had died in 1984, at 60 years old, but his photographs, records of dome construction, drawings, clippings, and other materials had been saved. “We were very fortunate that Lindsay could hold onto his archives for all these years,” McAtee added. “He really followed Fuller’s model of documenting everything, everything was filed, everything was kept.” (Fuller famously had a “Dymaxion Chronofile” which was an attempt to document his life as completely as possible, from his receipts to his thick-framed glasses.) Montréal’s Geodesic Dreams publishes much of Lindsay’s archival material for the first time.

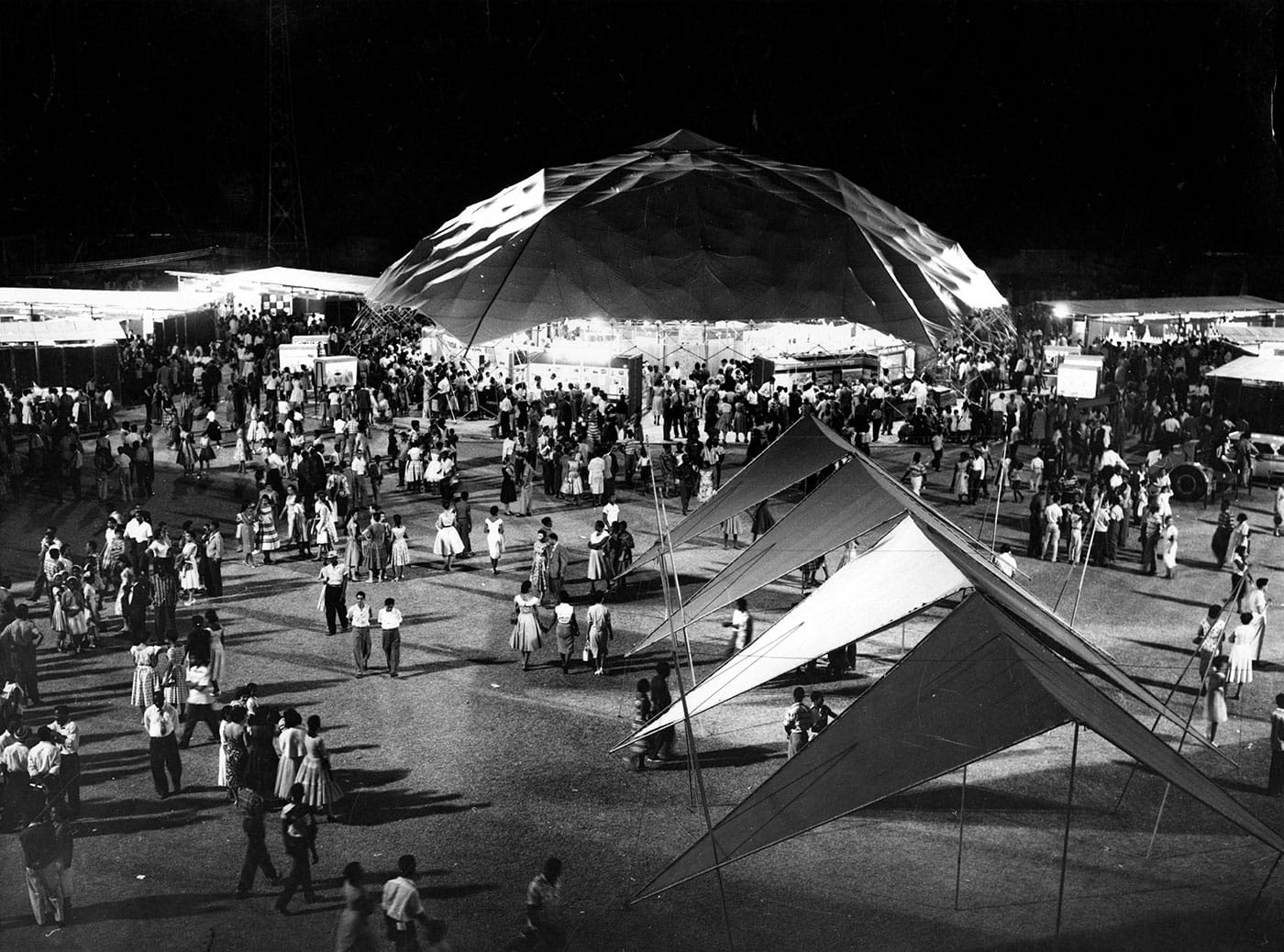

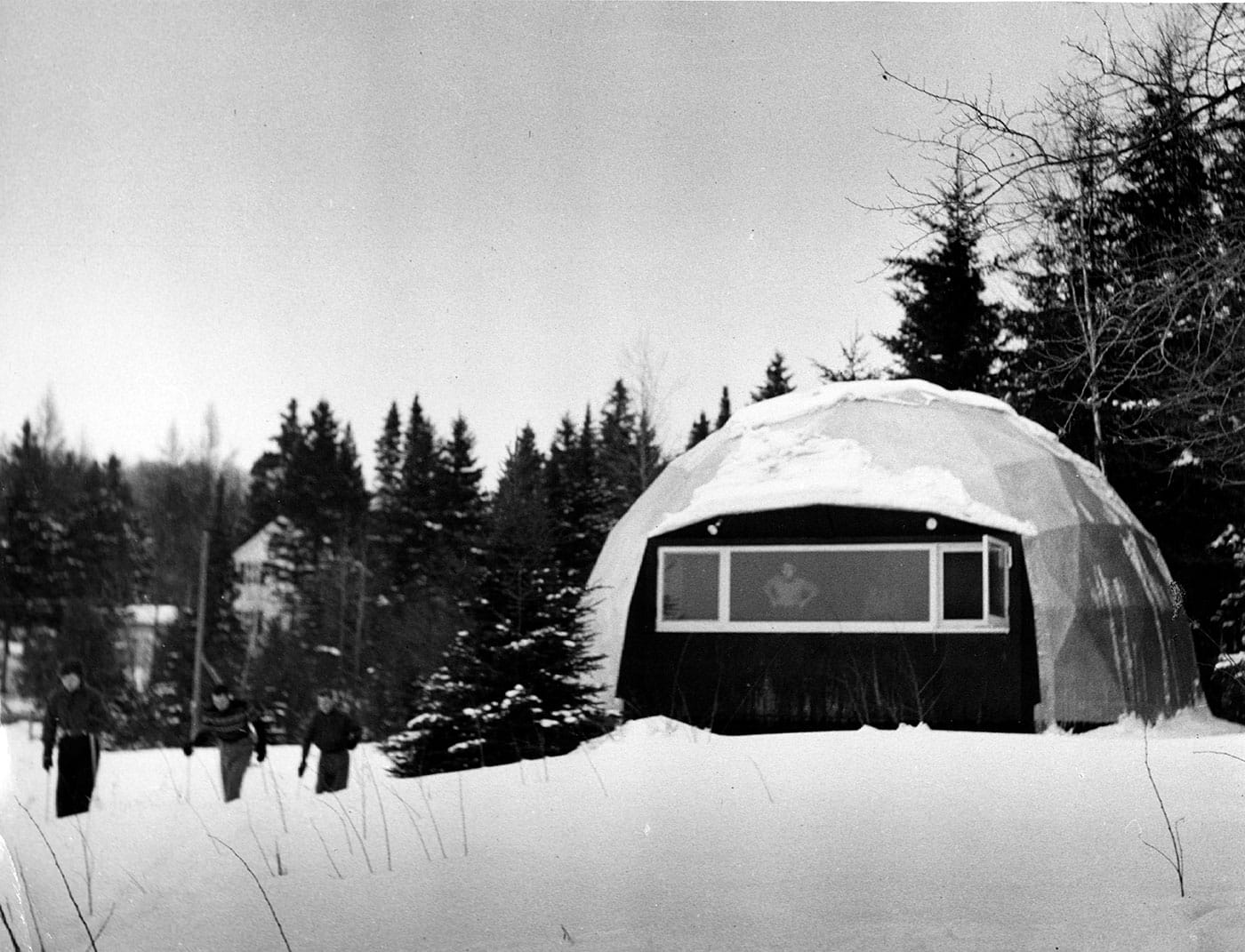

Lindsay relocated to the United States later in his career, when he’d moved on from the domes to other lightweight structures (he also worked on kite design). But for several years in Montréal, Lindsay focused on domes. From 1949 to 1950, he organized a team of friends to erect the aluminum and plastic Weatherbreak in Baie-D’Urfé, a suburb of Montréal. It was followed by Skybreak in Beaurepaire in 1951, and the Skigloo ski chalet in 1952 in Morin-Heights. The Hackney Barn (which sparked McAtee’s interest) was completed in 1954. In the 1960s, he brought his knowledge for creating these huge frames of space to Canadian architects Arthur Erickson and Geoffrey Massey’s designs for Simon Fraser University in British Columbia.

This exploration into the potential of geodesic architecture had a rippling influence in Québec. Mark Byrnes wrote about the Montréal’s Geodesic Dreams exhibition for CityLab, noting examples such as Paul O. Trépanier and Victor Prus’s geodesic polar bear enclosure at the Granby Zoo, a 1960s structure which still stands. Montréal’s greatest geodesic dome is the US Pavilion from Expo 67, designed by Fuller and Shoji Sadao. After it caught on fire in 1976, and its acrylic bubble was burned away from the steel icosahedron, it was transformed into an environmental museum, which is now called Montréal Biosphère. Although it is the most famous dome, by the time of its construction the “geodesic moment” of 1950s experimentation was waning.

Both the exhibition and book coincided with the 50th anniversary of Expo 67. While the Biosphère still looms over Montréal’s Parc Jean-Drapeau, Lindsay’s domes have disappeared. This is not just due to preservation issues; they were often meant to be assembled and disassembled when needed, like Lindsay’s geodesic tent made for an expedition to Canada’s Baffin Island. “They were in a sense ephemeral because of their ease of construction and dismantling,” McAtee said.

Lindsay’s archive is now part of the architectural collections at the University of Calgary, and the first dome that he designed in 1950 ended up being shipped to California and reconstructed with architect Bernard Judge, where it was photographed by Julius Shulman. It’s now on the shelves at the Smithsonian Institution. Although these tactile fragments linger, the domes were always more about the idea: about rethinking how we build and live, about how we use materials and challenging the supremacy of the right angle.

We may not live in dome homes, yet you can find their spacey forms at winter markets and as greenhouses, where up north in Canada they are used by Inuit groups to grow vegetables. There is a beautiful logic to the dome’s geometry that remains compelling. As McAtee said, “You have this ability to somehow understand it completely.”

Montreal’s Geodesic Dreams is out now from Dalhousie Architectural Press.