Dazzling and Didactic Board Games from the 19th Century

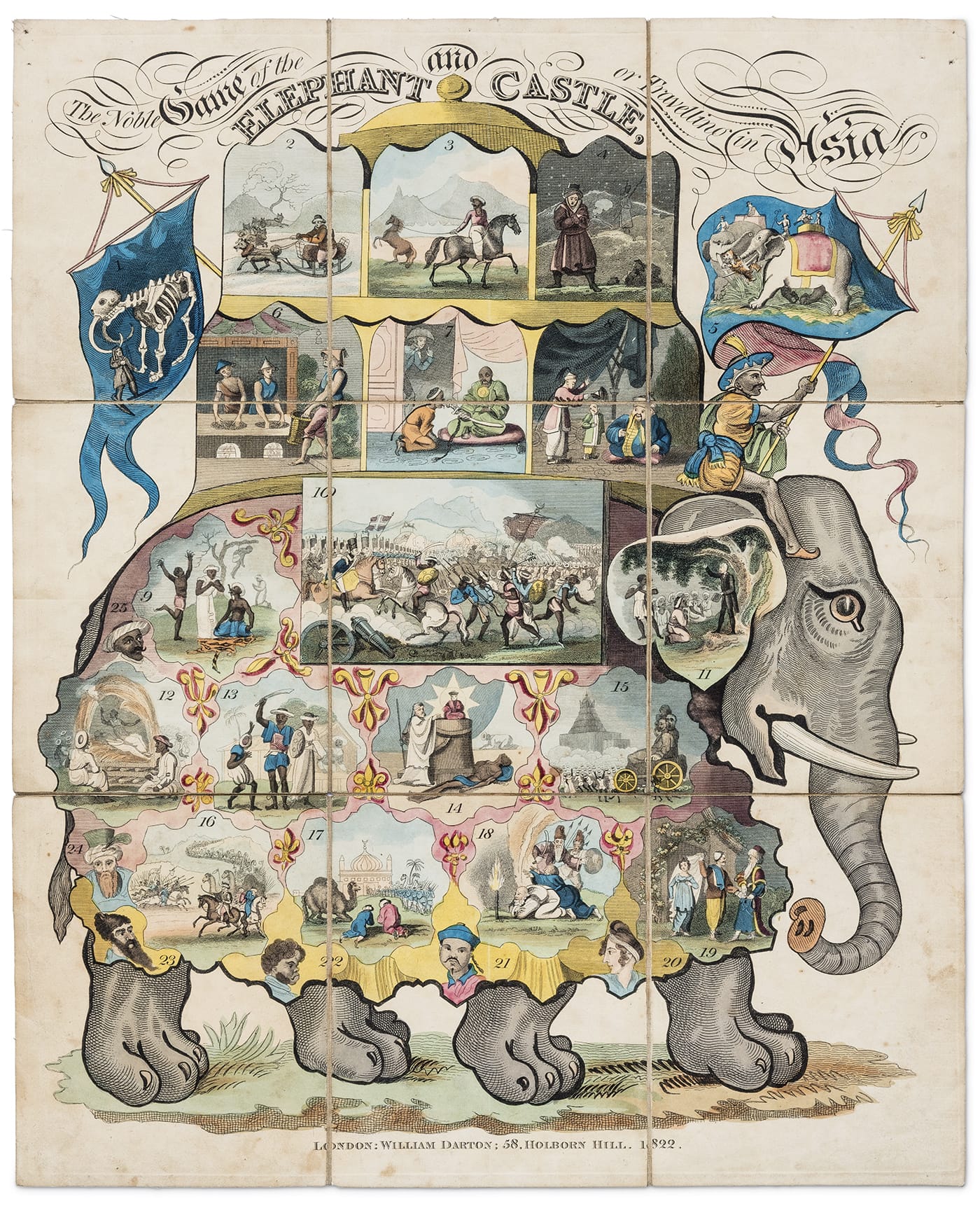

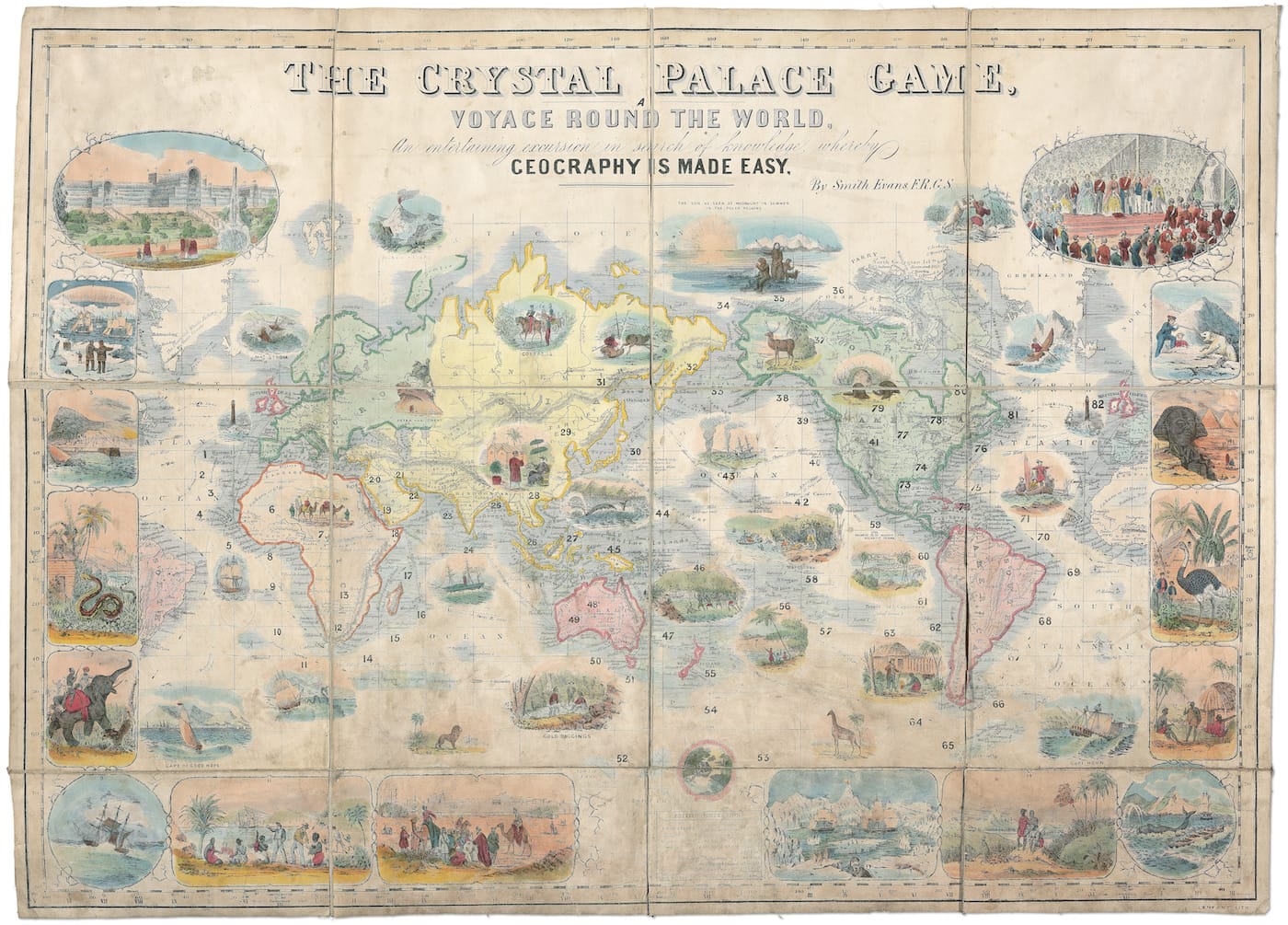

Games serve as curious records of 19th-century British beliefs and prejudices, reflecting the attitudes of a growing empire towards its own society as well as towards those beyond its borders.

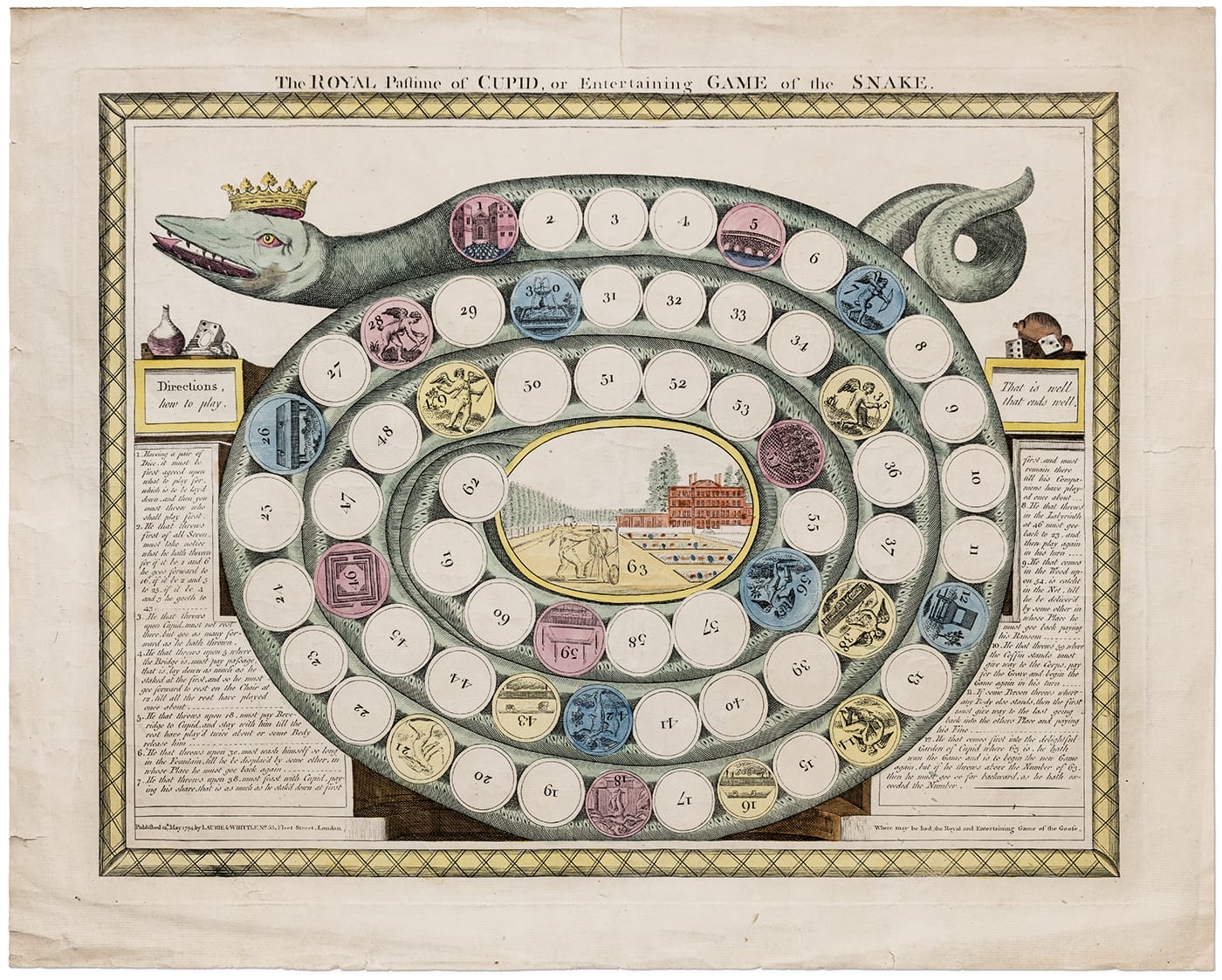

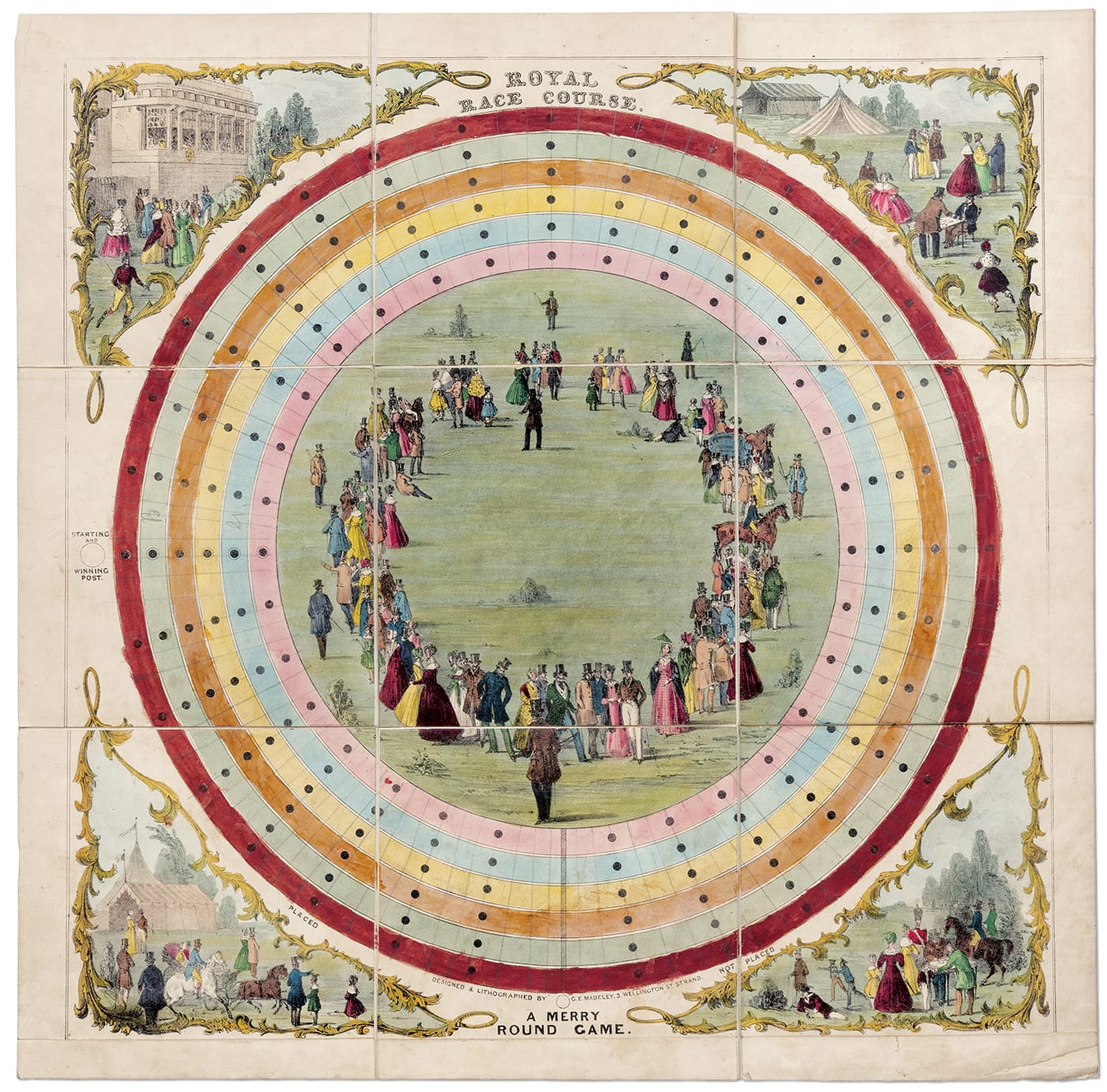

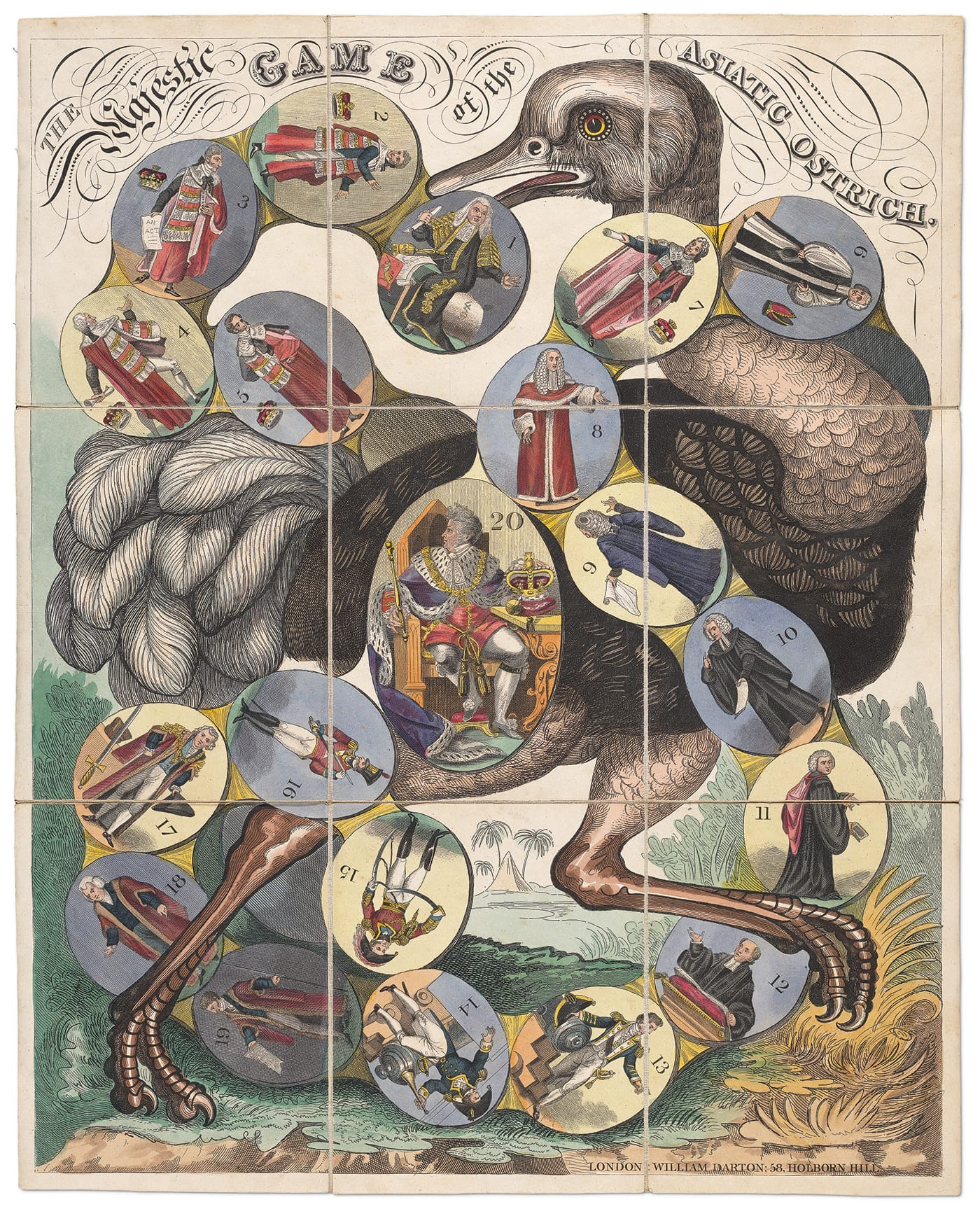

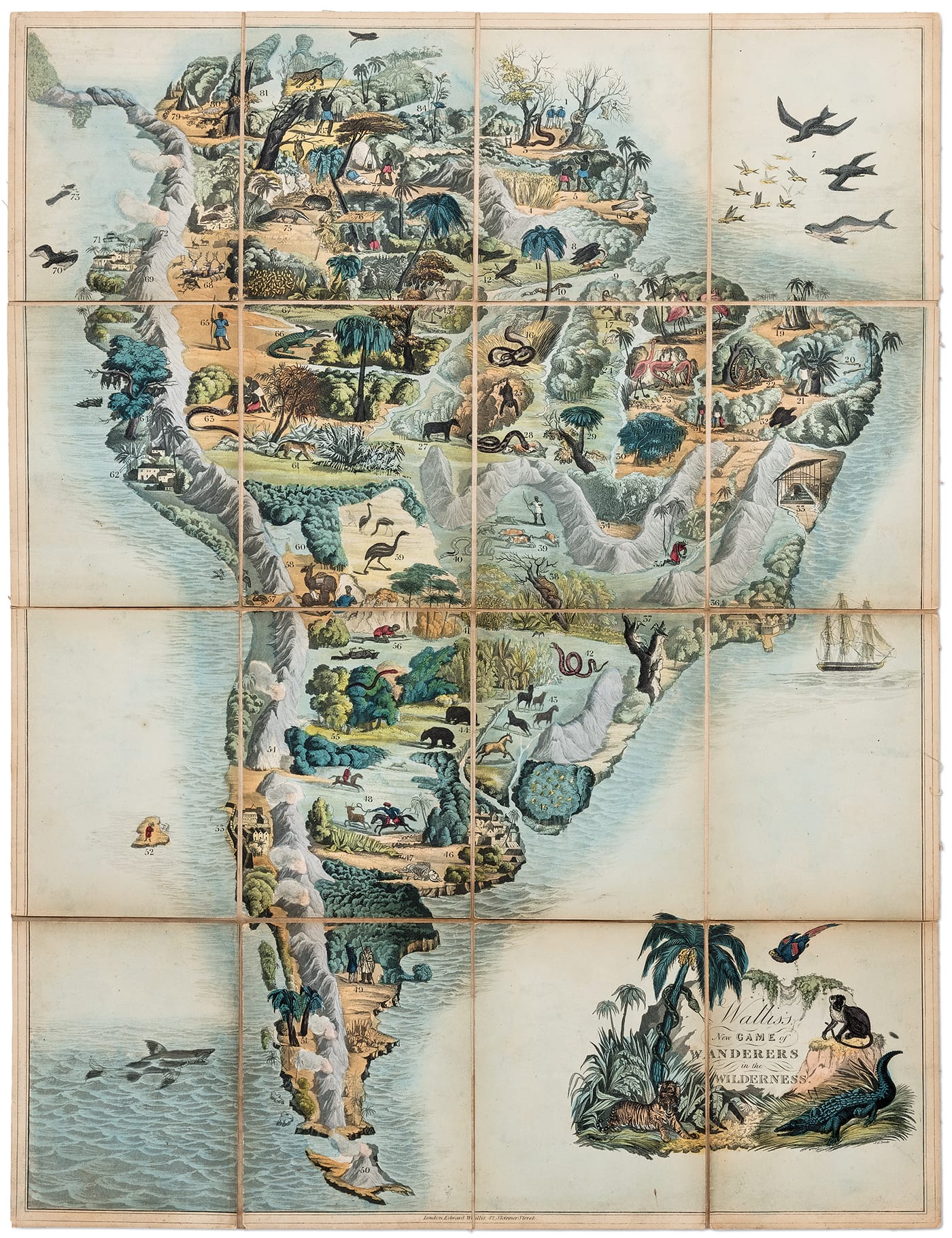

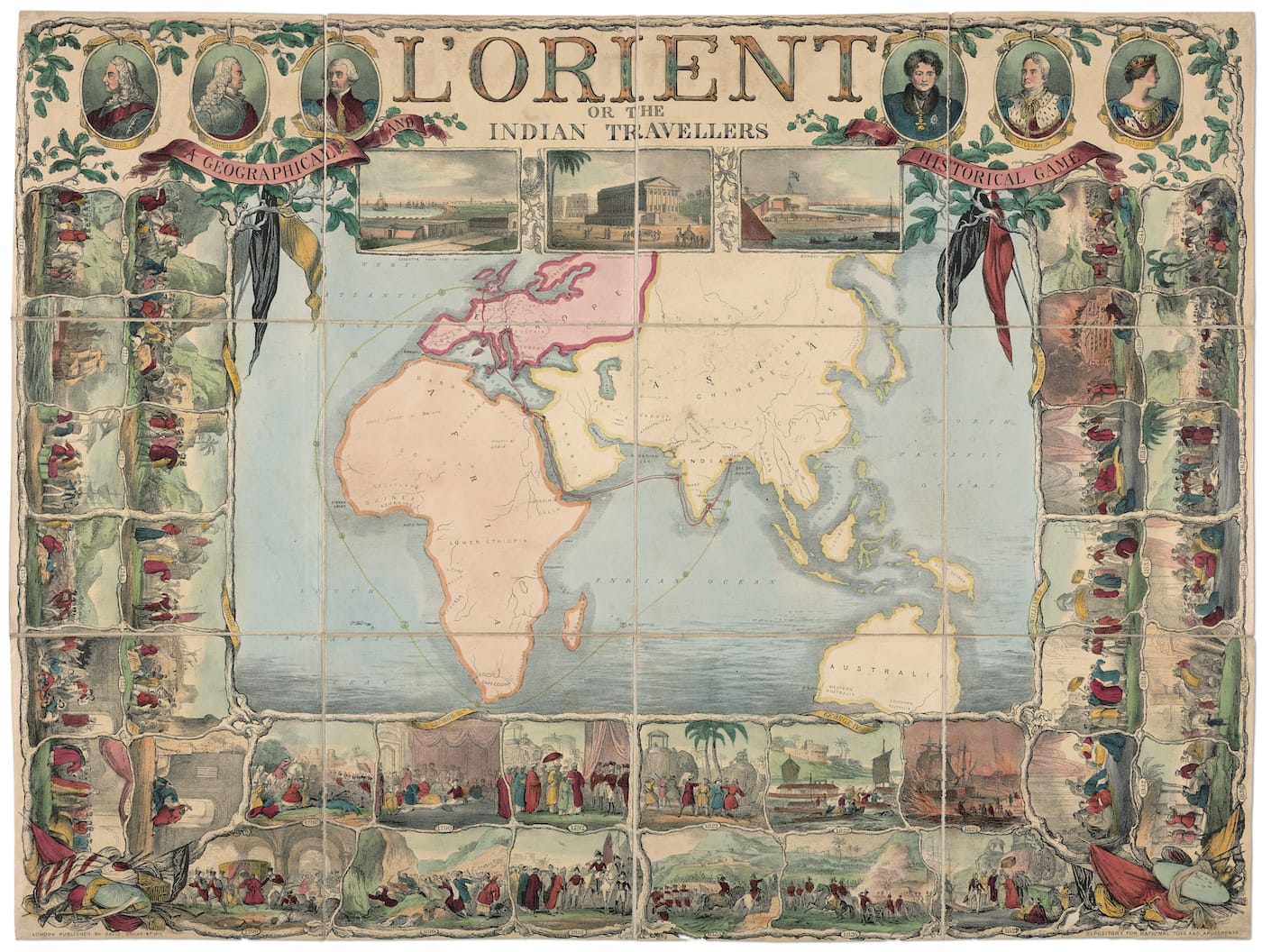

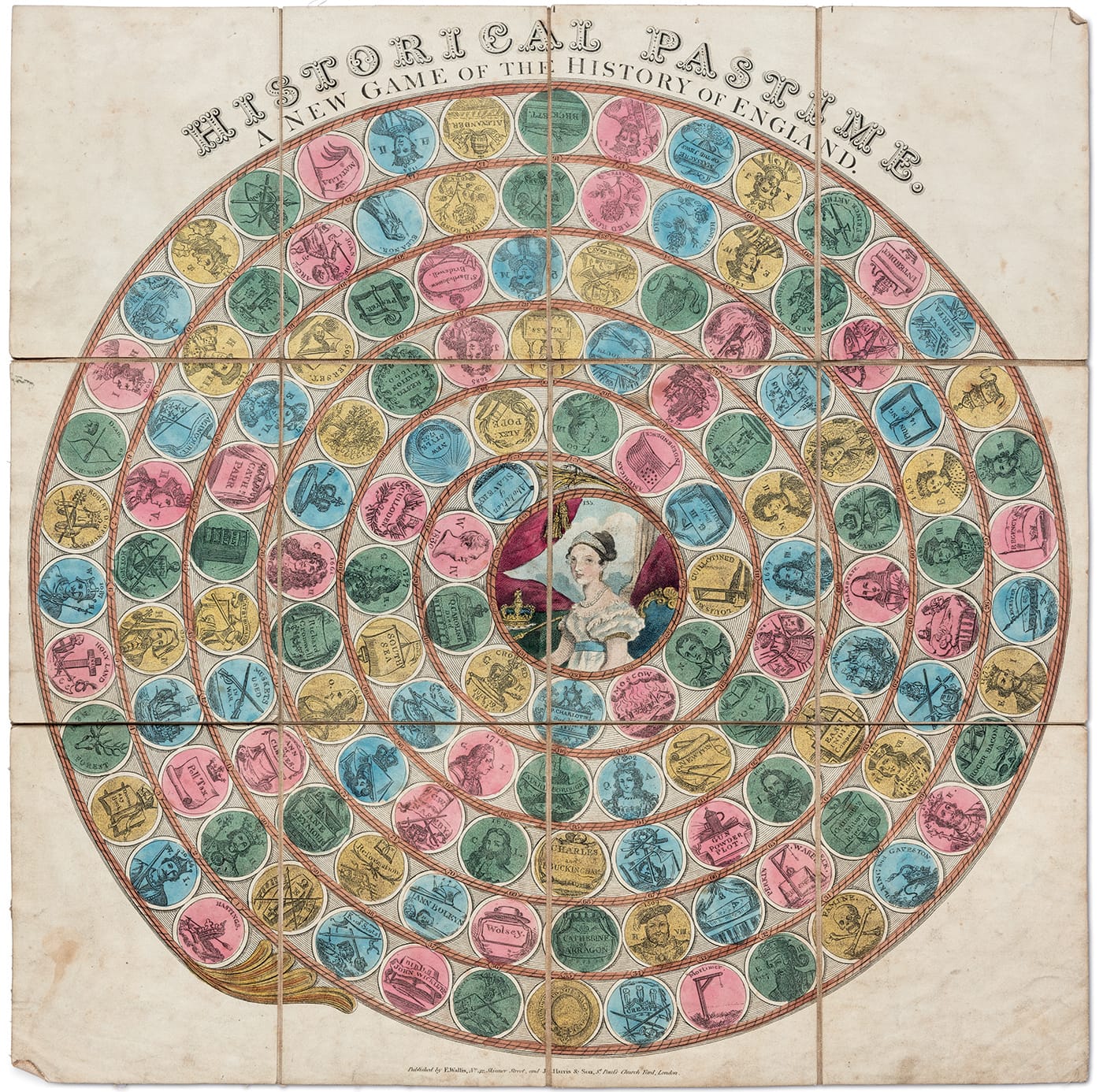

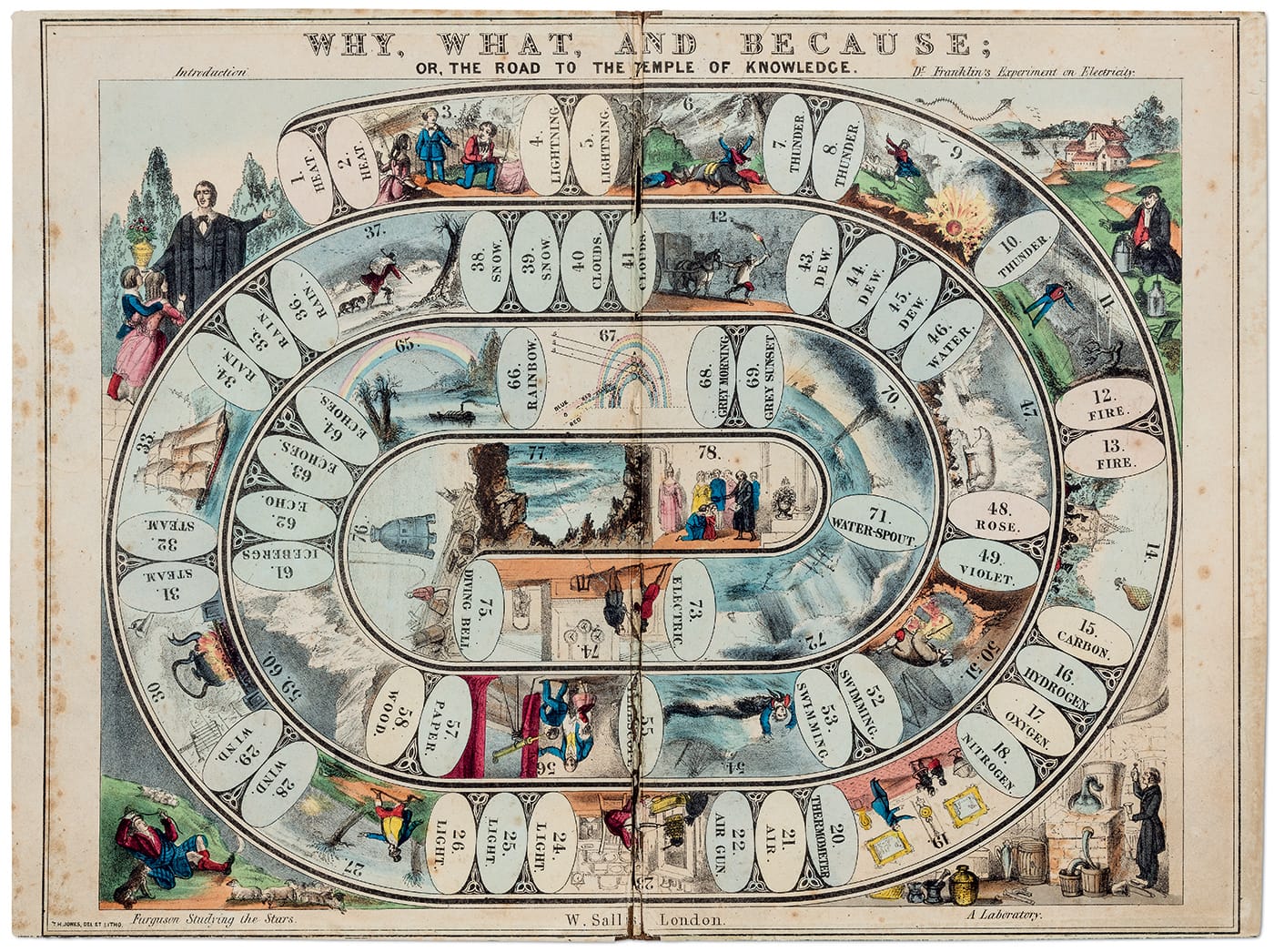

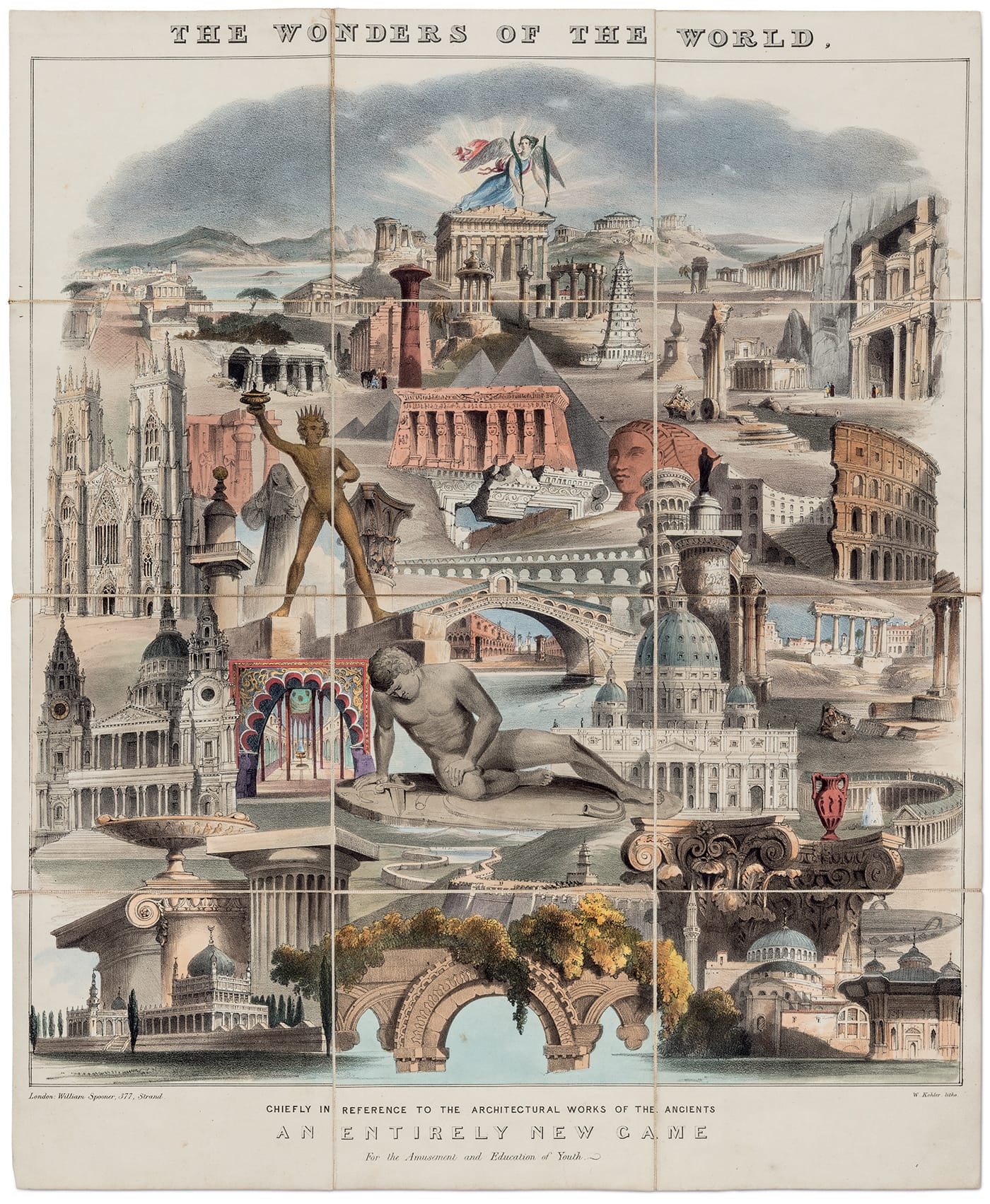

Around the early 1800s, British youth were gradually introduced to a new form of recreation: the board game. These activities, often hand-colored and printed on linen or board, were published by book manufacturers who competed to produce intriguing schemes and visually striking artwork. Parents, consequently, had a wide variety from which to choose, from race games — such as variants of the Game of the Goose — to trivia games.

For years, collectors Arthur and Ellen Liman amassed dozens of these now-uncommon artifacts by searching yard sales, flea markets, auctions, and online markets. Board games tend to fall apart with use, and many were discarded by their owners, but those that the Limans acquired were impressively intact. 50 examples, mostly from the 1800s, were recently compiled in a lavishly illustrated book published by Pointed Leaf Press, representing a half-century of this early social tradition in England.

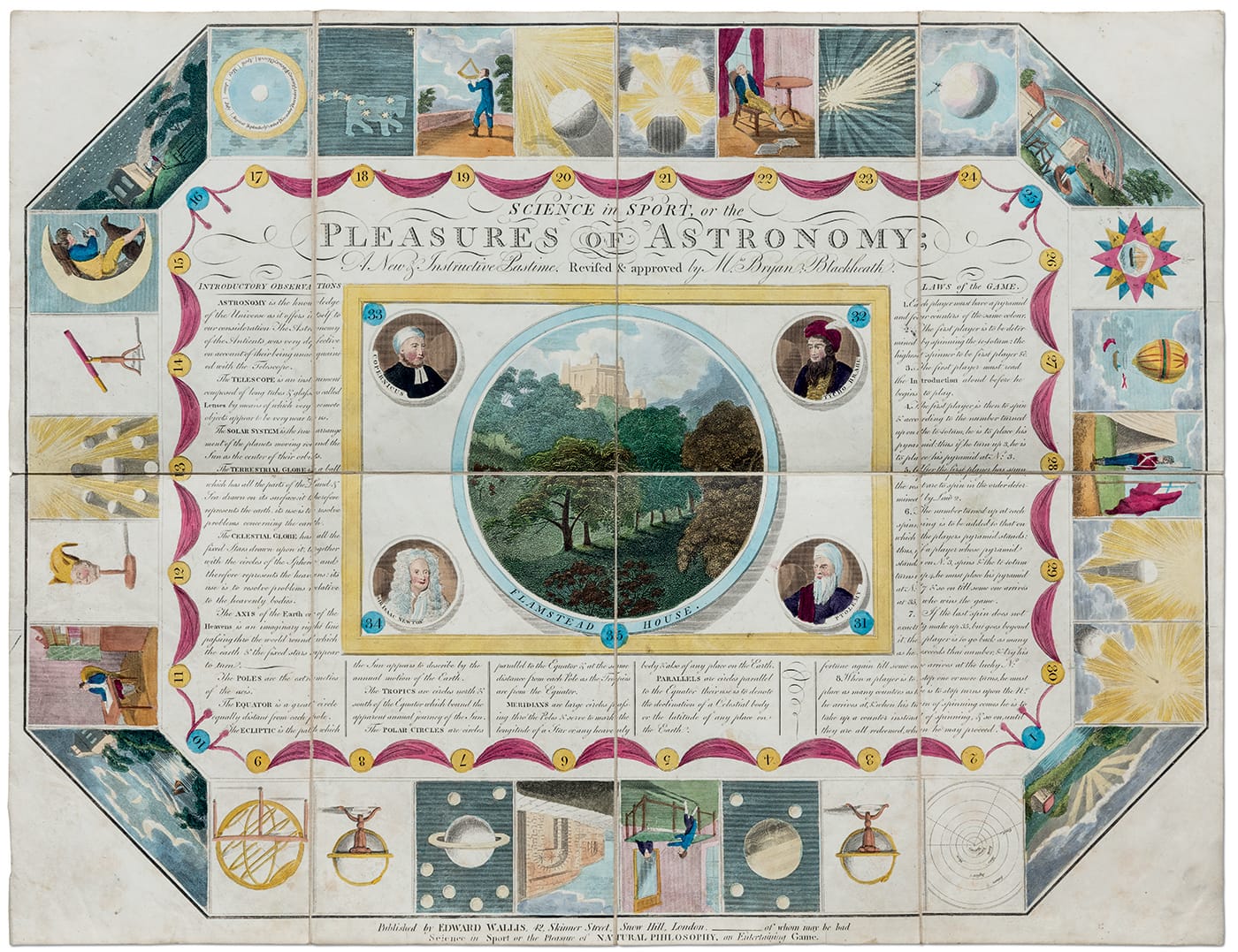

Georgian and Victorian Games: The Liman Collection is divided thematically to illustrate several trends. Some games were for pure entertainment, while others aimed to more deeply engage the minds of their young participants. There were games that dictated moral values as players advanced along paths towards virtues or vices; games designed around geography and British history; and instructive games, requiring players to memorize facts on subjects from math to astronomy.

Publishers deliberately merged education and entertainment: they shrewdly realized that such games would appeal to parents. A. Robin Hoffman, from the Yale Center for British Art, explains in the book’s introduction: “As the turn of the 18th century approached in Great Britain, more and more parents and teachers embraced a suggestion from the philosopher John Locke that ‘Learning might be made a Play and Recreation to Children.'” Publishers, she writes, had recently introduced the genre of children’s literature, and board games were the natural next step, particularly as printing technologies evolved.

“Advancements in manufacturing helped artists and printers to create games that were attractive, durable, and relatively affordable to the expanding middle class,” Hoffman writes. “Game designers directly benefitted from the same technological developments that illustrators increasingly exploited in both books and mass media; artists often simply transferred their skills to a similar environment.”

Vividly embellished as they were, the titles of these games weren’t exactly enticing. Take, for instance, “The Road to The Temple of Honour and Fame, An Instructive and Entertaining Game” (1811), or “Science in Sport or the Pleasures of Astronomy, A New Instructive Pastime” (1804). Such formal branding seems like a mark of the era, as are the social mores and norms illustrated on the boards themselves. More than just play objects, these games are curious records of 19th-century British beliefs and prejudices, reflecting the attitudes of a growing empire towards its own society as well as towards those beyond its borders.

While some express dated views, these games remain, after all, games. Georgian and Victorian Games: The Liman Collection is printed in an oversize format, which allows you to appreciate the impressive details that fill these boards — but best of all, the book has five gatefolds that open out to reveal five games. These are accompanied with their entire instructions, so you can host your own game night and revisit some peculiar diversions of yore.

Georgian and Victorian Games: The Liman Collection is out now from Pointed Leaf Press.