An Argentine Collective of Political Art, Re-examined

Alexander Apóstol’s current exhibition at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires doubles as a show of new work by a contemporary conceptual artist and a retrospective of the 1968 events.

BUENOS AIRES — In 1968, a collective of artists, intellectuals, and workers based primarily in the Argentinean cities of Rosario and Buenos Aires developed a series of exhibitions that would become a paradigm for political art. Their focus was the impoverished province of Tucumán, where military dictator Juan Carlos Onganía imposed a shutdown of sugar refineries under the shameful guise of establishing new, North American industries in the region. The collective condemned the Argentine government, which they accused of “pursuing a nefarious colonizing policy” at the expense of Tucumán’s largely sugar-dependent working class. Further incensed by the deliberate concealment and distortion of information by the government-backed media, the frivolous apathy of the leading avant-garde and the widening distance between art and reality, and the brutality of the ongoing war in Vietnam, the group mobilized the aesthetic and political effort Tucumán arde (“Tucumán is burning.”)

Its manifesto, authored by founding members María Teresa Gramuglio and Nicolás Rosa, declared the collective’s intention to “reveal the fallacious contradiction of the government and its supporting class” via a series of exhibitions joining art and activism; these included attesting to the degradation of Tucumán. They took place in the headquarters of the General Workers Confederation of the Argentines (CGT) in the cities of Rosario, Santa Fe, and Buenos Aires, rather than in traditional institutional spaces, in line with Tucumán arde’s critique of the latter and its firm stance on “the necessity of transferring [works of art] to another context.”

The history of Tucumán arde is the focus of Alexander Apóstol’s current exhibition at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA), Salida de los obreros del museo. Taller y República a partir de Tucumán arde. Presented on the occasion of the International Biennial of Contemporary Art of South America, it doubles as an exhibition of new work by a contemporary conceptual artist and as a retrospective of the 1968 events, incorporating historic material such as archival footage of sugar refineries and a typewritten manuscript of the collective’s foundational text.

Apóstol applies graph theory and information theory methods developed by Damián Horacio Zanette and Marcelo A. Montemurro to the manifesto’s linguistic structure, extracting from these applications a series of codes and instructions that serve as the basis for the works of art in the exhibition. Much like the 1968 collective, he enlists a diverse pool of collaborators for his project, including students from the Universidad Nacional Tres de Febrero in Buenos Aires and employees of MALBA. (It’s also worth noting that the press release refers to the trabajadores asalariados, the “salaried workers” of the museum, rather than empleados, “employees” — an important distinction because the term trabajadores aligns more closely with the identity of Tucumán’s sugar refinery workers, even though museum staff are normally referred to as empleados in Spanish.)

The exhibition begins with “Fábrica desde una inclinación a la derecha, fábrica desde una inclinación a la izquierda” (2017), wall drawings on a chalkboard depicting two factories in Buenos Aires: Industrias Metalúrgicas y Plásticas Argentina (IMPA), the first factory in the country to be reclaimed by its workers and re-established as a cooperative; and the now-closed Campomar factory. The latter operated according to a top-down management system and is currently under investigation for alleged involvement in the disappearance of workers during Argentina’s military dictatorship. Apóstol illustrates the respectively left- and right-leaning administrations by angling each image at a degree calculated from an algorithmic procedure — he divides the Tucumán arde manifesto vertically into left and right and calculates the median frequency of the terms in each partition. This gesture seems to echo a passage in the manifesto in which its authors described their commitment to evaluating “the degree of distortion” of information by the media.

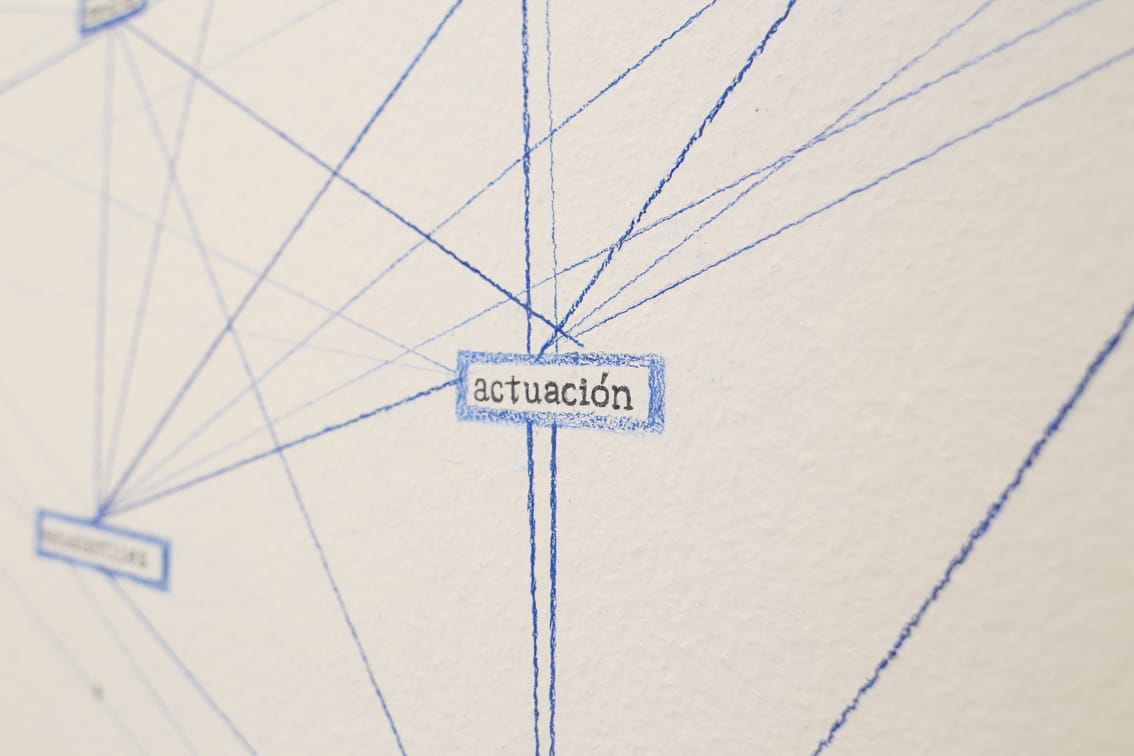

Although the artist’s native country is Venezuela — whose history is representative of Latin American class struggle — Apóstol’s visual rendering of polarization will resonate deeply with local visitors to MALBA. Argentineans are still reeling from the divisive events following the death of Santiago Maldonado, an activist whose disappearance during an indigenous rights protest in Patagonia last year spurred protests by opposition groups accusing the government of concealing Maldonado’s seizure and murder by security forces. Throughout the show, Apóstol brings the past to the fore, demonstrating Tucumán arde’s relevance in the present. His use of graph theory, which underlies the structure of digital and analog social networks, nods to the underground systems of communication that Tucumán arde relied on. The work “20 palabras significativas en azul” (2017), for instance, consists of a typewritten copy of the manifesto with twenty words circled in blue graphite. The terms were selected based on their information quotient — their ability to facilitate the most connections within the text. These connections are presented as a node-link diagram on the adjacent wall, the blue-on-white color scheme suspiciously reminiscent of Facebook’s visual identity.

There are moments when Apóstol’s methodology appears arbitrary, especially in the context of a radical political collective highly critical of the leading avant-garde’s inactivity and “precious aesthetic.” In Huelga y contexto: patrón numeral (2017), a 16mm film shown as a 5-channel video installation, the archival footage of sugar plantation workers in Tucumán is far more compelling than the analog animations that flicker in and out of the video, designed by five students of UNTREF according to structural coefficients from the manifesto.

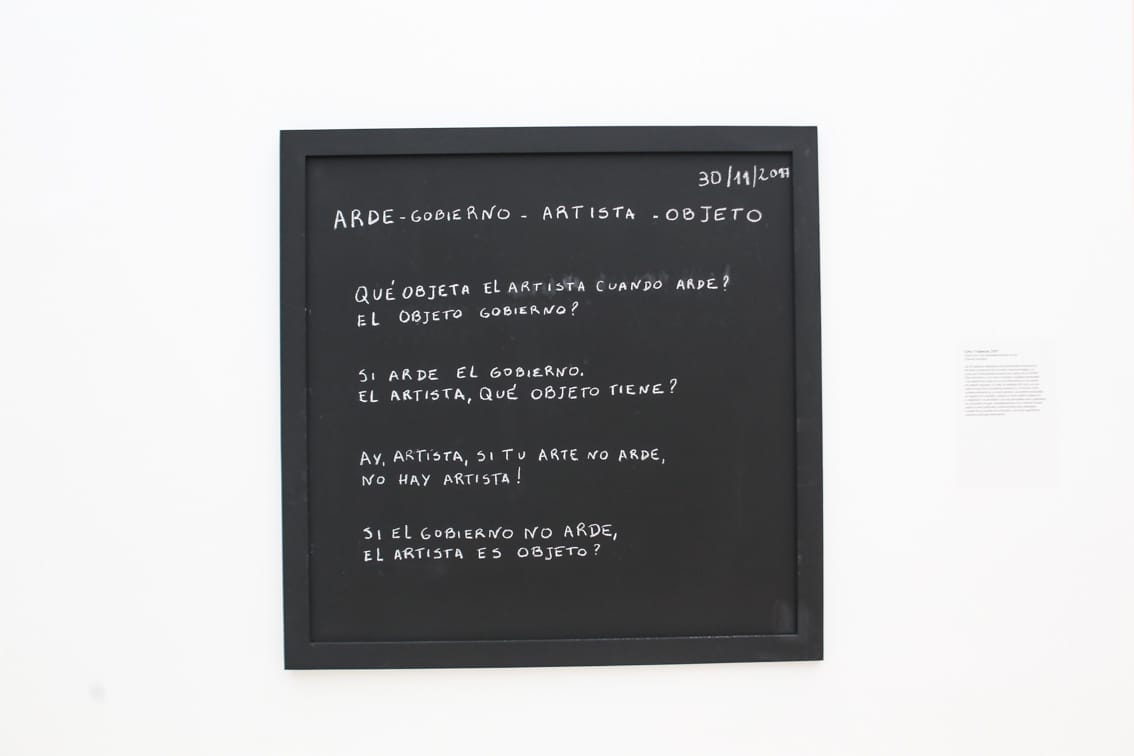

Juan Pablo Renzi, an artist and key figure of the Tucumán arde movement, once called for a “conscious incorporation of political action into artistic practice.” What would he think of Apóstol’s cerebral presentation, displayed in one of the country’s leading museums? Renzi would hopefully concede that replicating Tucumán arde’s strategies is not the only way in which art like Apóstol’s can mobilize action, provoke thought, and have social and aesthetic value. Apóstol is creating work in a far more forgiving environment than that of Argentina in 1968, and the times require a different arsenal for an Internet battleground. “Tuits y Trapecios” (2017), a chalkboard with rotating tweets written by forty UNTREF students using selected words from the left and right partitions of the manifesto, successfully forges links between the 1968 movement, the importance of collaboration and social structures, and the revolutionary power of social media.

Latin American conceptualism, as opposed to Western-born conceptual art, is a resolutely political practice: the dematerialization of the art object allows artists to convey subversive ideas while eluding authority and slipping by censors. As part of Tucumán arde’s exhibition in the city of Rosario, the lights in the rooms of the CGT building were dimmed every ten minutes to represent the rate of infant mortality in Tucumán. This symbolic feature was anything but straightforward. Yet, much like Apóstol’s codified structures, it stored and carried vital information. Salida de los obreros del museo recalls the power of the conceptualist gesture — the extraordinary weight of the dimming of the lights.

Alexander Apóstol: Salida de los obreros del museo. Taller y República a partir de Tucumán arde continues at the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (Av. Pres. Figueroa Alcorta 3415, Buenos Aires, Argentina) through February 19.