The Baroque Violence of Jusepe de Ribera

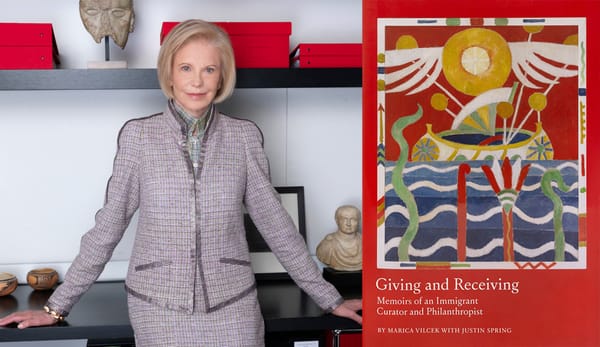

The UK’s first show of the famously gruesome seventeenth century Spanish painter places his monumental works in historical context.

LONDON — Dulwich Picture Gallery sits in a picturesque, well-heeled parkland area of south London, its relatively small galleries a destination for first-rate Reynolds, Poussins and Van Dycks as much as its cafe and grounds are for families and strollers on weekends. Searing through the serene comes Ribera: Art of Violence. It is the UK’s first show of the famously gruesome Spanish Baroque painter Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), presenting eight of his “most sensational and shocking” monumental paintings.

Dulwich director Xavier Bray was behind the same gory, Spanish brand of suffering depicted in The Sacred Made Real, at The National Gallery in 2009, which took a detached, rigorously academic look at shockingly realistic Spanish Baroque wood sculptures of flayed and decaying Christs and saints. With guest curator Edward Payne, a similarly anti-sensationalist approach is employed here, focusing on placing Ribera’s intellectual and spiritual concerns within a broader societal context. Captions diligently point out links between the paintings and carefully selected supporting drawings and sources within specific themes, including skin and the five senses, crime and punishment, and the bound male figure. The show’s approach makes for an extremely satisfying penetration of often repellently grotesque artworks.

The already scant temporary exhibition space at Dulwich is sparingly used; two full-size paintings of the “Martyrdom of St. Bartholomew” (ca. 1628, the other 1644) are spotlit in a darkened first room painted in a burnt-umber brown, mimicking Ribera’s dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, which illuminates the inverted saint’s glowing flesh in each work, his leering tormentors glowering above as he is flayed alive. A Valencia-born Spaniard, Ribera emigrated to Italy in 1606, and the dramatic influence of Caravaggio’s strong chiaroscuro is visible here, blended with a Velazquez-like sensibility for gutsier painterly details of flesh and physiognomy. Notably, Bartholomew’s flaying is not highlighted with brilliant red flowing blood, but is tucked into the background of the picture; in the foreground, the imploring, emphatic face of the saint gazes directly out of the pictorial frame. As noted in the caption for the 1644 Bartholomew: “As he peers out from the canvas and we stare back at him, our roles are reversed: the victim transforms into a viewer and we become the subject of his gaze”. In short, Ribera finds a greater punch in the psychological link with the viewer than the depiction of torture.

Nearby is a marble head from a Statue of Apollo, ca. AD120-40, a copy of the celebrated Apollo Belvedere, now in the Vatican, which, it is said, Ribera would have known. The bust is depicted face down in the 1628 Martyrdom, and its caption, in one neat sentence, summarizes both its art historical and spiritual/philosophical significance: “By placing this fragment face down, Ribera not only suggests his own rejection of Classical ideals in favor of naturalistic painting, but also evokes the blindness of idolatry versus the heavenly light of God to which Bartholomew turns his gaze”. Such clear, concise captioning draws on specific visual content to make the curators’ arguments with precision and economy, and is representative of the written captions throughout; there are no excitable grand claims or waffling general statements which can undermine a show.

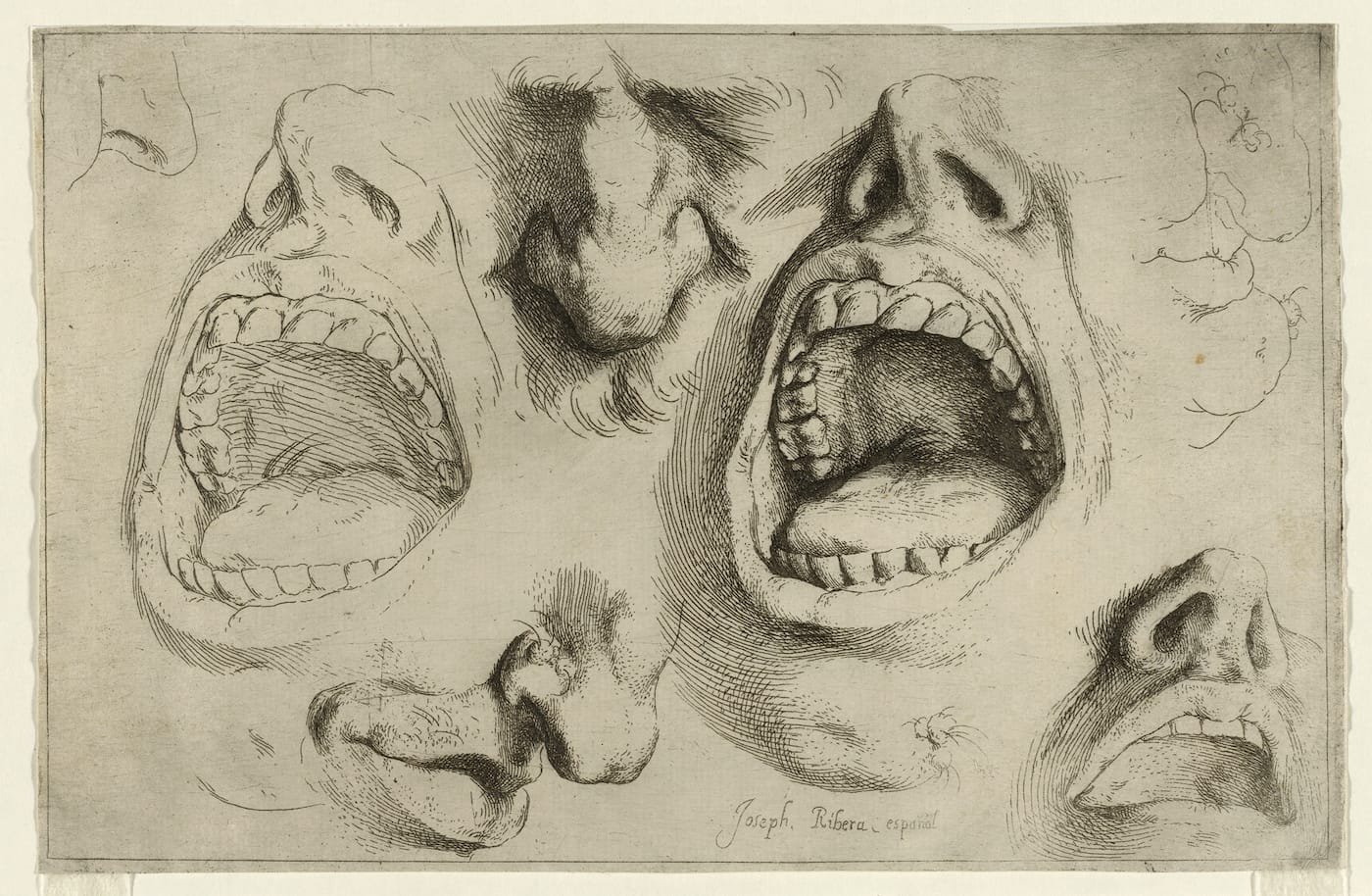

The same calm precision is employed in a section that links the skin as a concept to the flayed figure. In an astonishingly frank, half-length front-facing portrait from ca. 1612, St. Bartholomew holds a flayed skin as if it were a piece of drapery. Interestingly, there is no visible gore — blood is only alluded to by a deep red cloak — and the saint’s expression is stoic, not struggling. Displayed near the painting is a book from 1556, “Ecorché” after Gaspar Becerra, and engraved by Nicholas Beatrizet, open at a page showing an anatomical drawing of a flayed man holding his own skin over his arm in unmistakably similar fashion. Further emphasizing this implied idea of Ribera’s interest in skin anatomically, and as an entity in itself, is an example of skin as a canvas — in the form of an adjacent fragment of tattooed human skin from nineteenth century France. We become persuaded of Ribera’s intellectual consideration of the function of skin; he did not truck in shock for shock’s sake.

The concept of skin as entity leads into an examination of societal attitudes towards the body after death. The exhibition describes how, during Ribera’s lifetime, violent punishments for both religious and civil crimes were widely attended public events. Illustrating this are several of Ribera’s cursory sketches of public executions, such as “Inquisition Scene” (after 1635), conceived primarily as documentation rather than art. The inclusion of these sketches places Ribera’s violent works in historical context — his was an era in which public torture was routinely witnessed and recorded — suggesting they were not so unusual in their graphic content.

A section on “The Bound Figure” demonstrates Ribera’s consistent interest in the flowing contrapposto of the inverted male nude, which runs like a stick of rock throughout all the examples shown in the exhibition, from the flayed Bartholomew to paintings of St. Sebastian, who was shot by arrows at a stake.

The show’s conclusion occupies a room to itself; 1637’s “Apollo and Marsyas”, despite neatly tying up all elements discussed, is a gut punch of riotous color and squirming torture. A musing on the folly of hubris, it links back to the classicism of the first room’s Apollo head; here, the Greek god is depicted skinning the inverted Marsyas for daring to challenge him to a musical contest. Given the exhibition’s attention to the themes which informed the piece, however, we can find a way through the alarming subject matter; we notice the attention to contrapposto; the thematic function of skin, and the role of public torture in Ribera’s societal context. This is a masterclass in curating, with no superfluous images or filler, and thematic links made diligently throughout using close examination of content and treatment. It may be small, but this show proves you don’t need an excess of loans to demonstrate your thesis convincingly and economically.

Ribera: Art of Violence continues at Dulwich Picture Gallery (Gallery Road, London SE21 7AD) through January 27, 2019.