Women Artists Shatter the Stereotype of the “Valley Girl”

Valley Girl Redefined aims to challenge that very limited depiction of women from “the Valley.”

LOS ANGELES — Inspired by his teen daughter’s near-unintelligible “Valspeak” slang, Frank Zappa’s 1982 hit song “Valley Girl” parodied a distinct type of vapid, gum-chewing female Angeleno, who spends her days at the mall, gossiping with her friends. Followed up a year later by a Nicolas Cage film of the same name, the stereotype became a stand-in for Southern California in the popular imagination, but has its roots firmly in the San Fernando Valley, a sprawling area comprising parts of northern Los Angeles and the surrounding communities of Burbank, Glendale, Pacoima, and Calabasas to name a few. A new exhibition at the Brand Library in Glendale, Valley Girl Redefined, aims to challenge that very limited depiction of women from “the Valley.”

“This abstract idea of the Valley Girl, we always found humor in that. It’s not even close to the truth,” Monica Sandoval, one of the artists in the show, told Hyperallergic. “It’s crazy how far we are from the stereotype.”

Born in Van Nuys, Sandoval grew up in San Fernando and Pacoima, areas she said were far from the mall-littered landscape associated with Valley life. “There was nothing here but people living and working, no mall. Growing up, that was the norm; the surrounding community didn’t have wealth.”

Despite this, she said, “I absolutely identify as a Valley Girl. Even in High School, my friends would call ourselves the Valley Girls.”

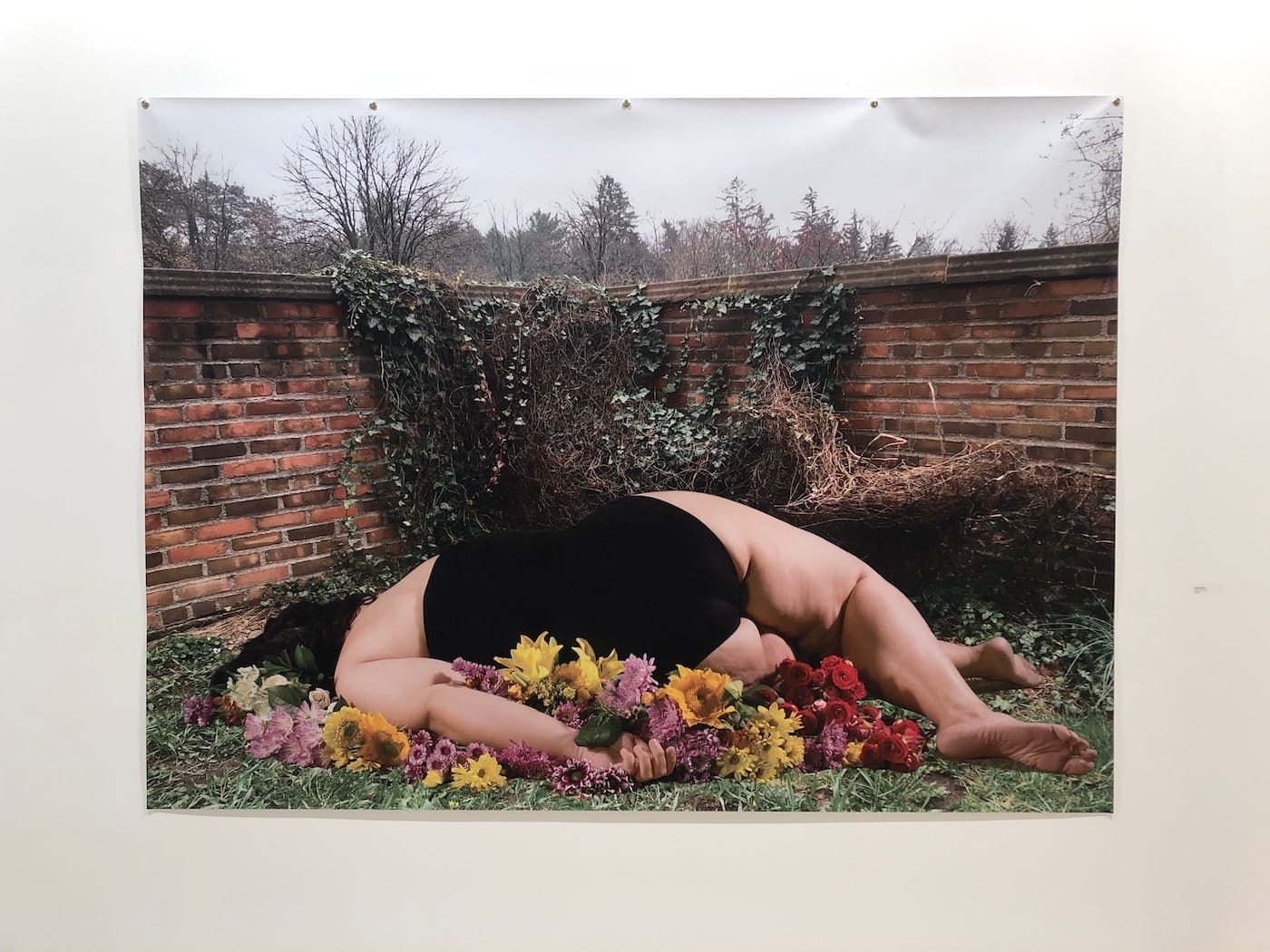

In “Together Again” (2016), a large-format photograph, Sandoval lies face down on a pile of flowers, seemingly having just fallen off a brick wall, à la Humpty Dumpty. “A lot of my work is reacting to the failure of desire,” she explains, “the desire to be the same as everyone else.” Another series of smaller photos, “want to be” (2018), isolates the curves of the artist’s body, turning them into abstract forms that are both sensuous and alien.

Across the gallery from “Together Again” are four photographs by Janna Ireland, depicting an African American woman sitting poolside, or standing in the midst of an orange grove. Taken at night, the dark, moody images place a Black female into idyllic Californian spaces — spaces more often associated with whiteness — while at the same time capturing a foreboding quality that conveys a sense of unease at her presence there.

Erika Ostrander’s column of hair, which extends from floor to ceiling, also plays with beauty standards. Since 2013, she has been collecting hair from friends and beauty salons in the Valley, weaving them into long strands on a spinning wheel, which is also on view. The column is dark brown in color — a far cry from the stereotypical blonde — alluding to the area’s diverse make-up, including Latino, Armenian, Asian, and African-American communities. “I think in my impulse to rewrite the body, definitely the label of the Valley Girl is ingrained in that,” explains Ostrander. “It was all I knew growing up.”

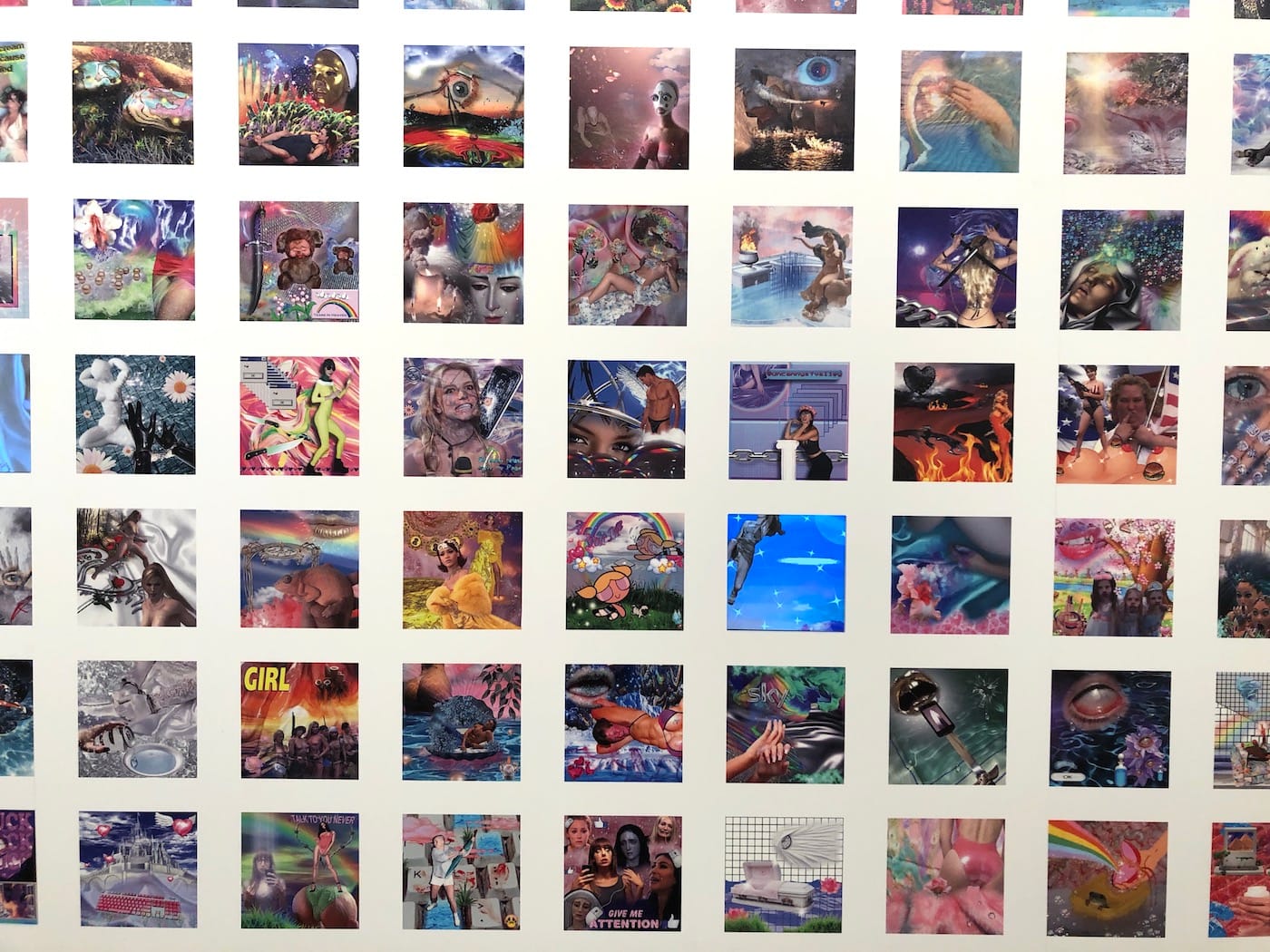

Other artists in the show feel more of a kinship with the stereotypical Valley Girl, even as they play with and push against its boundaries. “I didn’t realize what it meant until I went to college and people would do my accent back to me, ‘For Sure!’” Casey Kauffmann recalls. Her parents also fit the mold: her father made Barbie commercials, while her mom was a Valley pageant queen. Kauffmann’s main contribution to the show, and one of its highlights, is a grid of 300 digital collages taken from her Instagram account, which she posts under the name UncannySFValley. The images are a mash-up of pop culture, pornography, celebrity, cute animals pics, and internet memes, all set against against a sparkly rainbow CGI background.

For Kauffmann, the works’ gaudy, flashy veneer is a perfect metaphor for the Valley Girl. “Being from the Valley has a connotation of being déclassé, but trying to achieve an expensive look. After all,” she adds, “the Kardashians are from the Valley.”

Along the grid are several black rectangles, stand-ins for images that the show’s organizers opted not to include. Kauffmann speculates that they were too controversial for a publicly funded space like the Brand. (Nonetheless, she says she supported the decision to note their absence with black squares, as opposed to simply replacing them with other works.)

“I spent a lot of time at the mall,” said Michelle Nunes. “Fake nails and spray tans, it’s actually a part of who I am. I think I’m very close to the caricature.” Despite her identification with the Valley Girl, Nunes’s art is a far cry from superficial glitz. Dismayed by the rash of mass shootings in the country, her video “Little Liberty” (2017) features Nunes reciting the directions for installing a bump stock, while a censor bar with exploding fireworks hovers over her face. The work vacillates between discomfort and humor, as she stuffs her mouth with marshmallows, gagging and drooling through the recitation.

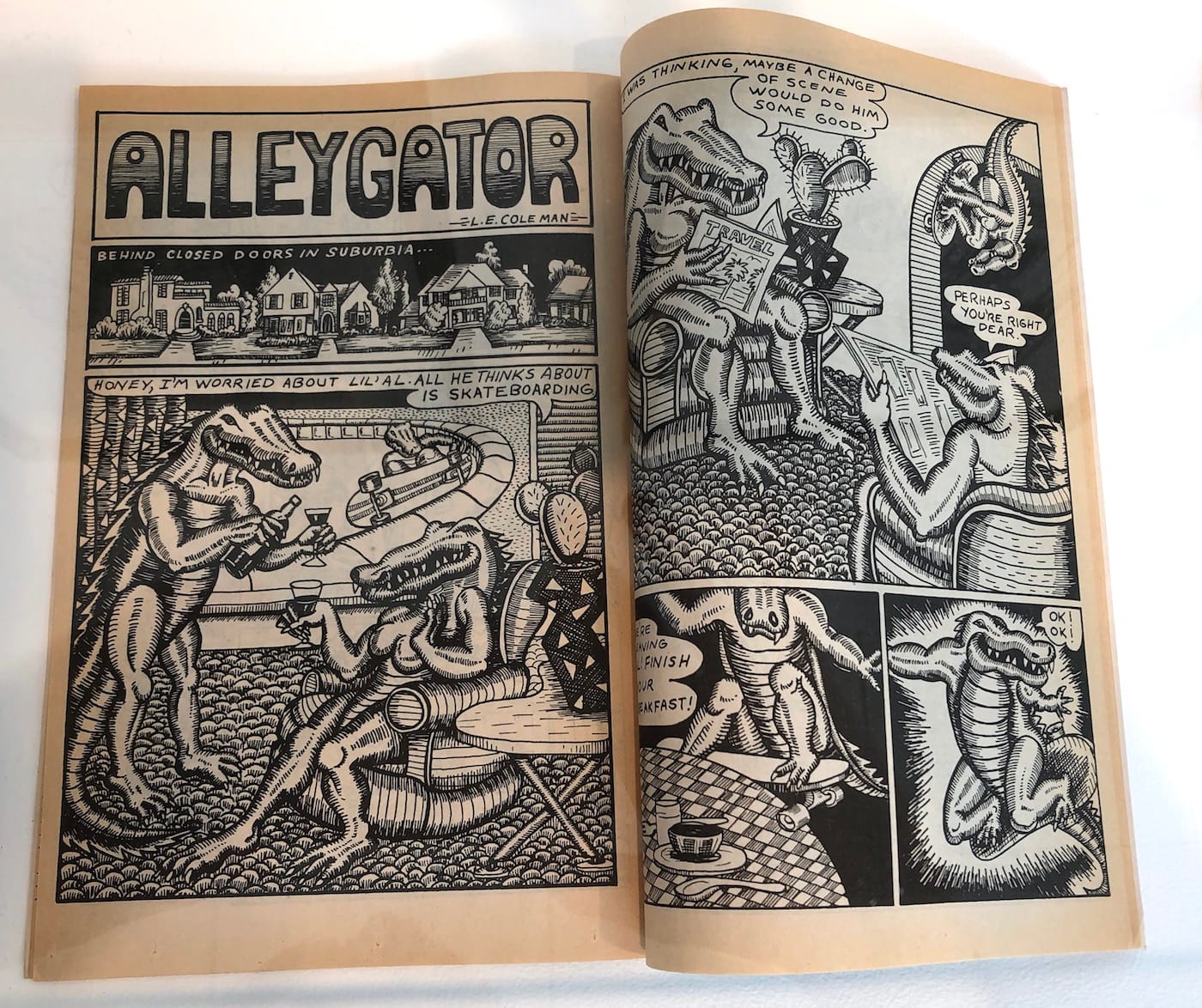

Alongside the younger crop of artists, Valley Girl Redefined features members of an earlier generation who began their careers before the ditzy, airheaded icon was codified. Lynn Coleman moved to Woodland Hills in the Valley as a young girl in 1962, and still lives there today. Even then, there was significant enmity towards Valley folks from residents of other parts of Los Angeles. As a surfer, she would hitch-hike to the beach to catch waves, “but if someone there learned I was a Valley Girl, I was persona non grata,” she recalls. “I couldn’t believe the prejudice. Spray painted on the rocks was, ‘Valley Go Home.’”

Coleman has displayed pages from her comic strip “Alleygator” about an eco-friendly, skateboarding alligator which ran in Thrasher’s short-lived comic magazine from the ’80s. Coleman lived near the tributaries that fed the LA River, which were being paved when she was growing up. This led to the inspiration for the comic, as she imagined the Alligator took up skateboarding on the concrete basin after the loss of his habitat.

Judy Baca, creator of the San Fernando Valley’s most well-known artwork, “The Great Wall of Los Angeles” mural, is represented with photos from her 1973 “La Pachuca” series, in which she portrays a campy version of the Latina bad girl. With her heavily made-up face, and teased hair, Baca could be seen as a browner precursor to the mass-market Valley Girl.

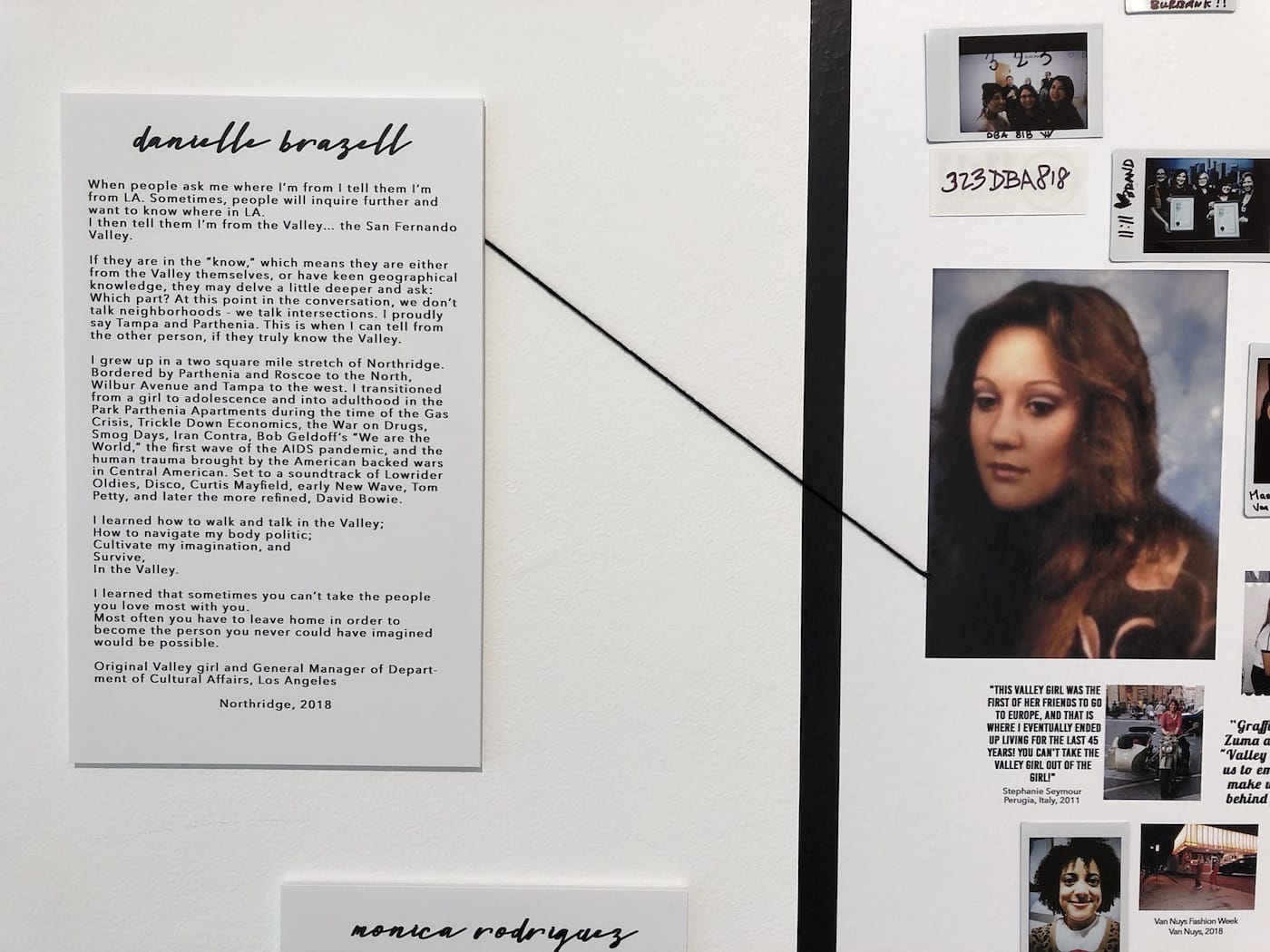

In addition to the artworks on view, curator Erin Stone spent four months collecting images and stories from Valley women, several of which are posted on a board reflecting a diverse populace. “Our goal is to reflect the actual community of the San Fernando Valley,” said curator Erin Stone, who is also the founder of 11:11, an arts collective based in the Valley. “The narrative of the ditzy, white, mall-going woman is the one the whole world knows. But the reality, the demographics, scream something very different.” A kiosk in the atrium holds dozens of local female-produced zines, allowing them another opportunity to control their own narratives.

Although the show does a good job of representing diverse perspectives, one oversight is the dearth of Armenian-American voices. This is especially glaring since Glendale is home to one of the world’s largest Armenian Diaspora communities. Stone said she did conduct interviews with some residents from Armenian backgrounds; however, given the Brand’s recent controversy over not including Armenian-American artists in its “‘Glendale Biennial,” a greater focus on their inclusion could have been expected.

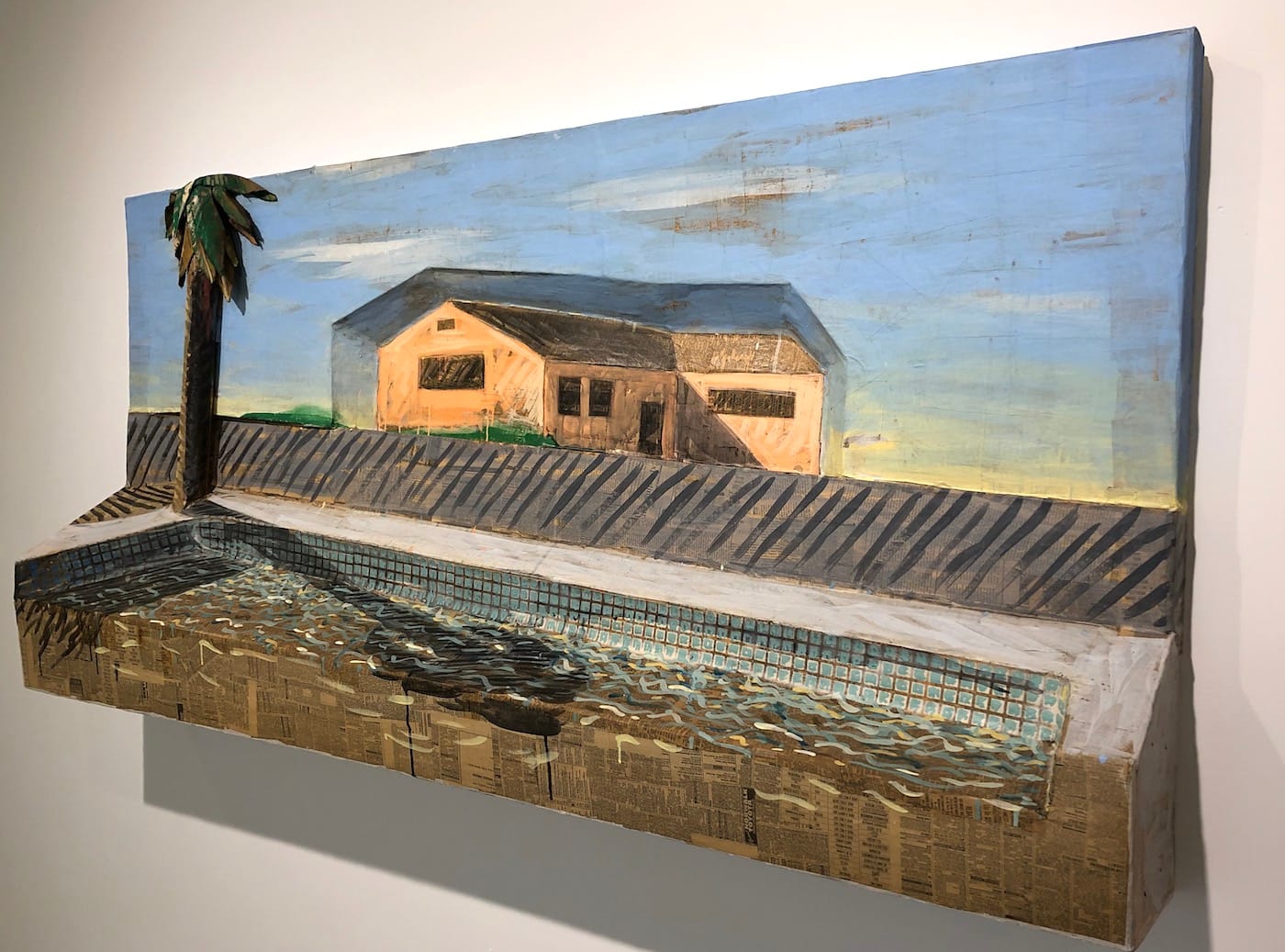

The artists that are included, however, explode the one-dimensional vision of Southern Californian femininity, offering alternatives vis-a-vis race, age, and beauty ideals. Much of the work is body-oriented, but even the artists that focus on the environment or built landscape present alternatives to the climate-controlled, bland suburbia that the Valley Girl occupies.

Under the superficial façade of the Valley girl, Kauffmann sees a more complex reality, which she naturally likens to Alicia Silverstone’s character Cher in the 1995 film Clueless. “Cher appears to be dumb but the whole film is about how she’s actually quite smart,” she says. “That’s the girl I love. I don’t mind having a Valley accent because I like being underestimated. If you look at this and just think ‘frivolity,’ that’s on you.”

Valley Girl Redefined continues at the Brand Library & Art Center (1601 W Mountain St, Glendale) through March 22. The exhibition was curated by 11:11 A Creative Collective.