Experience the Japanese Tradition of Silent Films Narrated Live

The UCLA Film & Television Archive is giving people in Los Angeles a rare chance to see this tradition in person.

What do you hear in your head when you read the intertitles while watching a silent movie? (I personally read all the dialogue in the most cartoonish Mid-Atlantic accented voices I can imagine. It feels appropriate.) The logistics and standards of Western cinema exhibition during the early part of the 20th century evolved to create this kind of personalized experience. It’s similar to how different readers will each “hear” a book’s dialogue differently. But this was not a universal experience. In Japan, a whole other performance tradition grew alongside silent film — one that continues today. The UCLA Film & Television Archive is giving people in Los Angeles a rare chance to see this tradition in person.

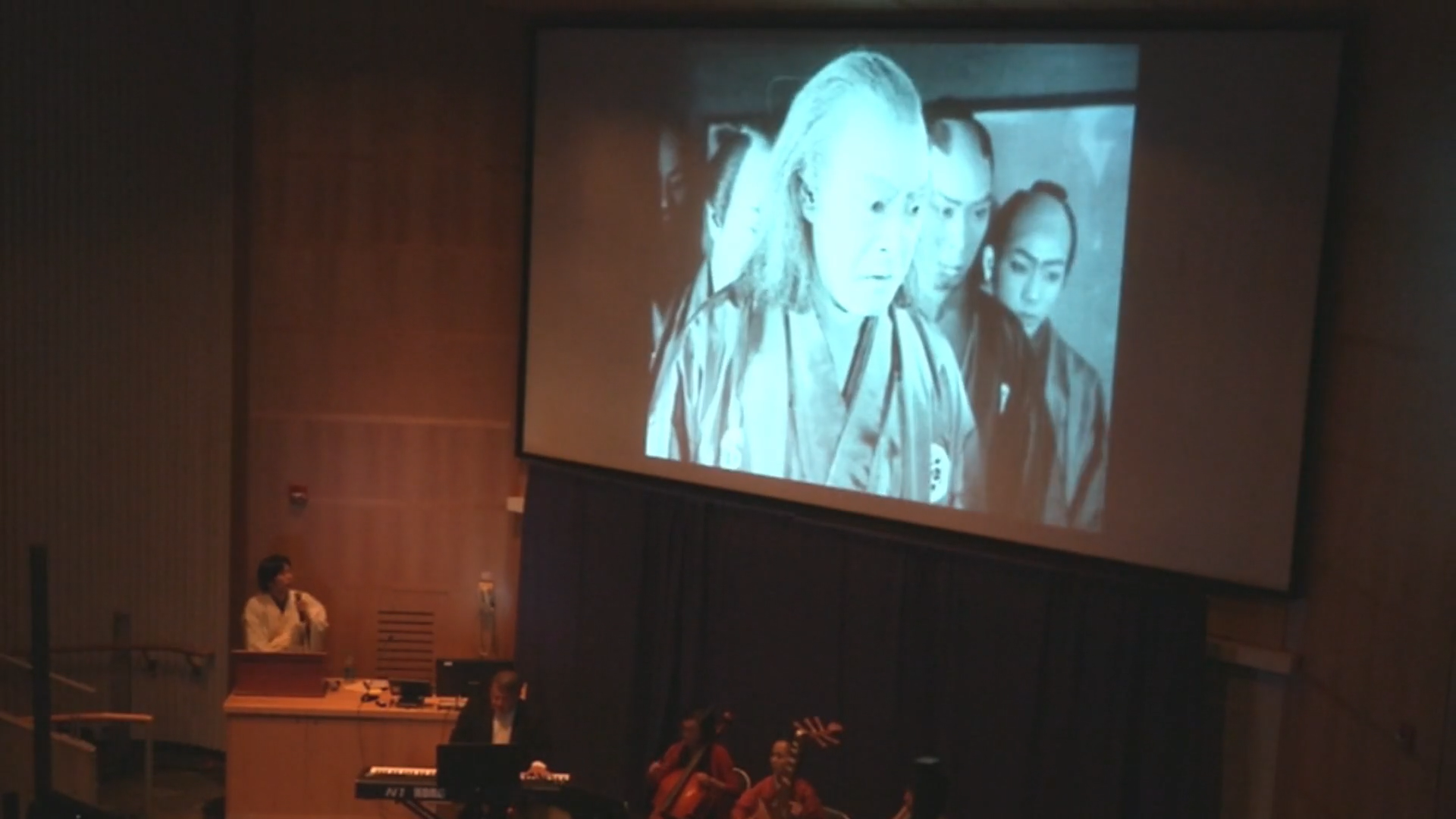

In “The Art of the Benshi,” UCLA will be screening a program of silent films along with musical accompaniment (including a shamisen) and live narration provided by modern Japanese benshi. But to describe benshi simply as narrators doesn’t do justice to their trade, which has both a rich history and layers of artistic nuance.

Narration plays an important part in traditional Japanese theater forms, such as kabuki and Noh, and the benshi role came out of this. Benshi were initially employed to introduce films during the silent era, summarizing their stories and settings (this was particularly important for foreign imports). Soon, however, they were also accompanying the films themselves, reading the dialogue (essentially dubbing the film live) and describing the action.

Benshi were an intrinsic part of Japanese moviegoing in the 1920s and early ’30s. The performers became stars in their own rights, commanding high pay and attracting audiences with their own names on marquees and their own faces on posters. A skilled benshi had to not just narrate with aplomb, but also perform characters, avoid clashing with the live orchestra, and crucially, project their voice so they could be heard throughout thousand-seat movie palaces.

Various nuances and styles emerged within the benshi model. For foreign films, one benshi would perform all a film’s characters, while showings of domestic films utilized kowairo setsumei (“voice coloring”), in which an offstage team would act out the voices. Contemporary opinion was split over which was superior. And of course, there were those who disdained the practice as a whole. The Pure Film Movement, which criticized the influence of theater on Japanese cinema, decried benshi as outdated. While proponents were able to get many updated cinematic techniques incorporated into domestic filmmaking, they were unable to drive out the benshi.

Of course, the advent of sound film did eventually render the narrators obsolete, though it was some years into the ’30s before the change took full effect. A few benshi keep the art alive today, their skills having been passed down through generations from the original readers.

Three of them — Ichiro Kataoka, Raiko Sakamoto, and Kumiko Omori — will be performing as part of UCLA’s series. To demonstrate how a benshi can make a difference in a film’s exhibition, a surviving scene from the mostly lost 1928 film Blood Spattered Takadanobaba will be shown three times, each with a different narrator. The rest of the program features a mix of features and shorts from the ’20s and ’30s, with a wide range of genres (period drama, crime, action) on display. The films are mainly Japanese, though there are a few American films, including the long-lost, recently rediscovered and restored 1926 crime drama Silence. Other titles include the influential samurai film A Diary of Chuji’s Travels and celebrated auteur Yasujiro Ozu’s gangster flick Dragnet Girl. With four events over three days, the series provides ample opportunity to indulge in this very different way of watching old movies.

“The Art of the Benshi” will be running at the Billy Wilder Theater (10899 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles) March 1–3.