The Death of a Contemporary Art Museum Highlights the Need for Cultural Funding

The dream of an independent institution specifically oriented towards contemporary art in Honolulu was effectively foreclosed when it was recently announced that the HMoA's satellite, Spalding House, would be sold.

HONOLULU — When the Honolulu Museum of Art (HMoA) announced in July its plans to sell a satellite exhibition space known as Spalding House, the statement to its members and the press put an end to a longtime dream. The vision was to make the mansion and grounds in the hills behind the city an oasis for fine art in a community with very few well-funded institutional options for showing and collecting new or provocative work from Hawaii, the mainland US, and elsewhere. The elegant 1920s house and three-and-a-half-acre estate has been owned by HMoA for the last eight years. Prior to 2011 — and this is where the real story lies — Spalding House was the home of the Contemporary Museum of Honolulu (now referred to as TCMHI, but then known as TCM), a vibrant, independent institution founded in 1986, that specifically showed newer art. For 23years the gem-like TCM was the only alternative to the more conservative, institutionally top heavy Honolulu Academy of Art, as the HMoA was then known. But then the two merged in 2011 — actually TCM literally gave itself to its erstwhile rival — the result of a financial panic at both museums caused in part by the recession of 2008. Spalding House, the Contemporary’s collection, and a substantial endowment were then absorbed by the Academy of Art, along with ten members of the Contemporary’s board of trustees.

A HMoA FAQ webpage from 2011 assured the public:

The merger has made contemporary art more accessible to the public and reflects a commitment to all cultures and types of art, including the great art of today … Now, all the art can be put in the context of 5,000 years of art from around the world, spanning from a Neolithic Chinese stoneware jar to a mixed-media wall relief sculpture by Frank Stella.

You can’t really fault the public relations department back then for putting a spin on a dismal situation. The recent announcement about the sale of the house, however, is a reminder of both promises broken and ambitions related to the property left unfulfilled. It also shows just how difficult it’s been for international and local contemporary art to find support in the islands.

Spalding House itself was commissioned in 1925 by Anna Rice Cooke, the widow of one of Hawaii’s sugar barons and a daughter of American missionaries. It was Mrs. Cooke — a sort of patron saint of Western art in what was then the Territory of Hawaii — who founded the Honolulu Academy of Art in 1922, giving to the organization the site in downtown Honolulu where her 19th-century Victorian manor once stood and where the HMoA stands now. Her new house, in the quiet Makiki Heights area above the city, designed in a regional idiom combining Modernism with traditional Chinese decorative details, offered a stunning view of lower Honolulu and the Pacific Ocean. When she died in 1934, Cooke left this second house and estate to her beloved Academy which the trustees subsequently sold, that is, sold for the first time.

The house eventually ended up back in the hands of one of Cooke’s descendants named Spalding, then later was purchased by a local businessman named Thurston Twigg-Smith who had made a fortune publishing the Honolulu Advertiser newspaper. (He sold the paper to Gannett, owner of USA Today, for $250 million dollars in 1992.) A significant collector of contemporary art and stamps, Twigg-Smith was at one time chair of the Whitney Museum’s board of trustees’ National Committee and a major donor to the Yale Art Gallery. In Hawaii, Twigg-Smith had the reputation of iconoclast and rogue, not at all a toady of old money, after having ousted his uncle in a takeover bid at the Advertiser and directing his paper to endorse Daniel Inouye, a Japanese-American, when he first ran for US Senate in 1963 against a scion of the white upper class. Converting Mrs. Cooke’s old house from a residence to a contemporary art museum, which he opened to the public in 1988, though the act of a passionate art collector to be sure, was also one more way Twigg-Smith thumbed his nose at the establishment. From then until its closure, TCM would compete directly with the Honolulu Academy of Art for funding.

Rivalry aside, TCM was a tremendous addition to the cultural life of Oahu for 23 years. Twigg-Smith’s own holdings were part of the founding collection, but during its short life the small museum gained a solid reputation for engaging exhibitions and especially for introducing Hawaii to the artists themselves — not just the work. That dialogue, not only between the art and the city but between the visiting artists and the artists of Hawaii, is perhaps the most important contribution TCM made. Part of its deliberate programming was that conversation, and the intimacy of the house and lovely gardens loaned itself perfectly to it.

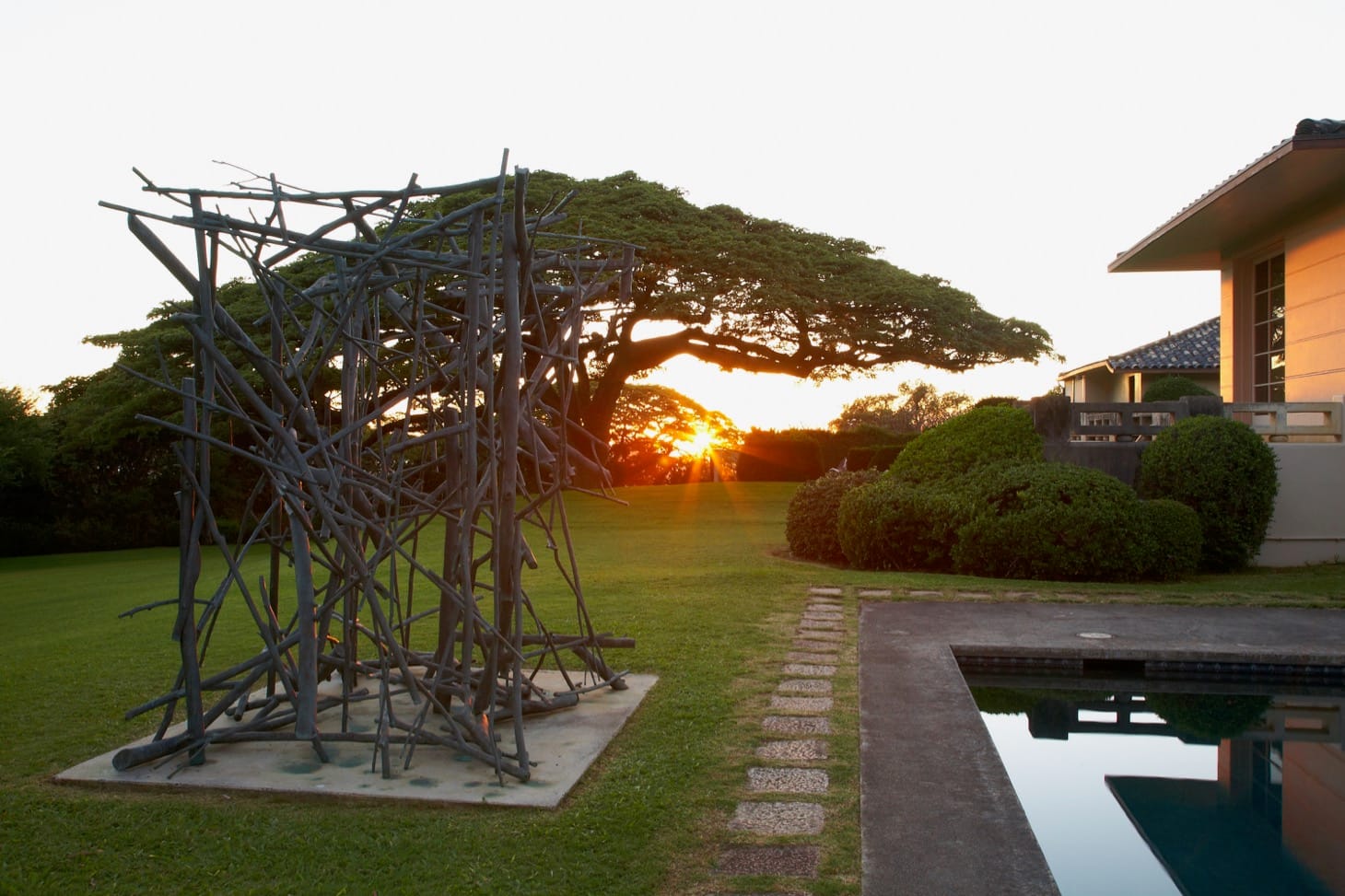

For over two decades artists from Susan Rothenberg and Bruce Nauman, to David Nash, Patrick Dougherty, Vic Muniz, Futura 2000, Richard Misrach, Paul Pfeiffer (a Honolulu native) and Yoshitomo Nara, to name a few, exhibited or made site-specific work for the museum. A sculpture by Jed Garrett greeted people arriving at the house. A Deborah Butterfield horse still sits on the lawn in the hillside garden, near where Dougherty wove his enormous sculptures from found sticks. David Hockney flew to Oahu for the permanent installation, in the estate’s pool house, of the original 1981 sets he made for the Metropolitan Opera’s production L’enfant et les sortilèges by Maurice Ravel. TCM gave Oahu, and especially its artists, for that brief moment in time, a kind of casual yet meaningful contact with the rest of the world no other Hawaii institution did or does to this day, outside the poorly funded art department at the University of Hawaii. As John Koga, a Hawaii-based sculptor put it, “We had so much fun up there.”

In many ways TCM was doomed from the start, the most obvious reason being the arts donors club in Hawaii was and is a limited group. The same names showed up on lists of contributors for both the Contemporary and the Academy, TCM having failed to create enough of a solid patronage foundation entirely its own. Around the same time TCM folded, the Honolulu Symphony filed for bankruptcy after a 110-year history. (It has since reopened.) This was part of the argument made for the merger before it happened, and the rationale offered the public after it was a fait accompli. For the Contemporary there was another hurdle, however. The Makiki Heights neighborhood, in part made fashionable when Mrs. Cooke and a number of other members of the Cooke dynasty built there, is one of Honolulu’s most affluent and desirable places to live. Well-healed neighbors never embraced Twigg-Smith’s vision and fought hard to limit parking and nighttime activities that any art museum needs to remain healthy. And when the museum purchased an adjacent property and proposed to the city an expansion, it received a resounding “No.” The neighborhood was also thought forbidding by many young and working class, non-white, Oahu residents — exactly those members of a diverse audience the museum sought.

The question asked by interested parties then and now remains: Why didn’t the TCM board sell the very valuable house and property and build a new home in a different area, one more accessible to local people and tourists, with greater impact, and without such zoning restrictions? Kaka’ako, for instance, always came to mind: the light-industrial neighborhood near downtown. The answer given a decade ago was, that despite its strengths, Kaka’ako is in Oahu’s flood plain and therefore vulnerable during hurricanes; yet it seems that good design could have overcome such obstacles. Maybe TCM had simply run out of gas, or perhaps its board and staff were too attached to the gracious confines of Spalding House.

It’s impossible to say if any one party was responsible for the demise of an independent TCM. Twigg-Smith, who died in 2016, should still be applauded for his efforts, along with the museum’s staff. At the time, the merger was deemed a financially propitious move: “The combined assets of both institutions puts the new, single museum on solid financial footing, making it easier to negotiate the fluctuations of the economy and the donor community in particular,” according to the HMoA FAQ from 2011. The Academy — rebranded as HMoA as a result of this rejiggering — was strapped after a succession of exceptional but costly block-buster-scale exhibitions, including Life in the Pacific of the 1700s: The Cook-Forster Collection (2006) with thousands of Pacific region artifacts collected by Captain James Cook on two of his voyages, and The Dragon’s Gift; the Sacred Arts of Bhutan (2008), the first time Bhutanese art was ever shown outside of that nation. The latter went on to the Rubin Museum in New York and received rave reviews, but HMoA failed to sell the show to other organizations to pay back its investment. The recession in 2008 made matters much worse, halving that institution’s endowment.

Meanwhile, the Contemporary, which underwent a series of cost-cutting measures including the firing of half its staff, seemed safe. Yet Georgianna Lagoria de la Torre, the Executive Director of TCM at the time, recently confirmed that Twigg-Smith actively shopped TCM to the board of the Academy. He was convinced TCM was finished. The Contemporary died in those months while the HMoA may have been saved by the move. As Lagoria de la Torre put it, “It wasn’t a merger, it was an acquisition.”

To some in Honolulu the impending sale of Spalding House marks a disappointing denouement; to others, particularly younger artists or those who arrived on Oahu’s shore more recently, TCM is simply a thing of the past and the Spalding House gallery of HMoA worth visiting just for the quiet and the view below.

There is a discernible buzz in the Honolulu art world today, but it’s coming from a spate of hip, dual-purpose exhibition spaces — restaurants, cafes, or luxury high-rise apartment building foyers — where artists hang their own work (sans curatorial discernment), and from the cinder block walls of some of the old warehouses and Quonset huts in Kaka’ako now decorated with murals and real estate developer-funded graffiti. First Hawaiian Bank (affiliated once with TCM and now with HMoA) has a history of showing accomplished Hawaii-based artists, most recently the paintings of Hadley Nunes, and the Arts at Mark’s Garage continues as a small, independent, alternative exhibition space after a number of decades. The second Honolulu Biennial was another brief spark on the island. Conceived by a non-profit start-up without any major institutional anchor, private or governmental, it’s the brain child of an ambitious group of younger art entrepreneurs, who hope to plant Honolulu on the art world (and art fair) map. Scant attention from outside the islands was paid the 2019 three-month-long, city-wide installation called “To Make Wrong/ Right/ Now,” despite, or perhaps because of its focus on indigenous people’s art of the Pacific region. The biennial even had to compete with a lively rival survey exhibition in town at the same time called iBiennale created by a disgruntled former partner.

Challenging, international contemporary art has always struggled to capture the attention of any but a very small share of the local population in Hawaii. (There are no galleries specializing in anything but decorative, genre, or antique paintings.) The remote archipelago has been an American state for over fifty years, but there remains a sense that the Western-style institutions planted by the colonial culture — including art museums and theaters — are an imposition rather than that which grows naturally here. The arts from beyond the ocean often feel like potted palms in the middle of a jungle. But the closed-mindedness of some towards the creativity of the outside world is antithetical to the ancient Hawaiians who welcomed the arts and technology brought by haole (foreigners), absorbing and adapting them. Despite the many secondary places where local painting, sculpture, and performance art thrive, a noticeable gap remains in the consistent collection and preservation of new art, an absence that falls heavily on the shoulders of the city’s museum professionals and wealthy arts patrons. Most saddening, however, is the dearth of that dialogue between the best of everywhere else and Hawaii, in Hawaii, for which the demise of the Contemporary Museum eight years ago is partly to blame.

Editor’s Note: Due to a publishing error a version of this piece was mistakenly published earlier in a truncated form. The full version of the article is now above.