The Ghosts and Zombies of Haiti's Colonial Past

Zombi Child and Ouvertures delve into France's lingering influences on Haiti.

In 1791, the enslaved people of the French colony of Saint-Domingue took up arms and liberated themselves. Today, Saint-Domingue is known as Haiti. Yet despite sounding the death knell for the African slave trade, the Haitian Revolution is often relegated to the footnotes of history. Is this a product of the Western-centered gaze, or does it speak to a darker facet of society? How has the world’s most successful slave uprising been so easily forgotten? These questions came to the fore in several films which played at this year’s London Film Festival.

The Haitian Revolution struck fear into the hearts of the slave-holding classes, and in an attempt to diminish its impact, Haiti was often presented as inhabited by dangerous savages. Central to this was the appropriation of the zombie myth, which first entered the Western imagination via William Seabrook’s 1929 book The Magic Island. The novel has since been dismissed for its conspicuous racism, but it fueled the archetypes of deranged cannibals and evil Vodou priestesses that permeated Hollywood films of the era. Originally, the zombie curse reflected enslaved Haitians’ fear of being imprisoned in their bodies for eternity, but over the years, the zombie’s links to Vodou have vanished. What was once an embodiment of Haiti’s colonial past is now a constantly evolving metaphor for Western society’s anxieties.

The legacy of this erasure is explored in Bertrand Bonello’s Zombi Child, which interrogates the relationship between white privilege and the evolution of the zombie myth. Schoolgirl Melissa (Wislanda Louimat) enrolls at a prestigious boarding school, where she develops a friendship with a white girl named Fanny (Louise Labèque), who invites her to join a secret sorority. After Melissa reveals that her aunt is a Mambo (a Vodou priestess), Fanny decides to visit her in the hope that black magic can cure her broken heart. But Fanny’s sense of entitlement to these mysterious powers sees France’s colonial past come back to haunt her.

At one point in the film, renowned historian Patrick Boucheron makes a cameo, delivering a semi-improvised lecture on French liberalism and how it obscures actual liberty. This reinforces that cultural appropriation has contributed to the disembodiment of black and marginalized bodies in contemporary France. His ideas reverberate more clearly Louis Henderson, Olivier Marboeuf, and the Living and the Dead Ensemble’s Ouvertures, an experimental exploration of the role language has played in excluding Haitians from their own history. Creole is the mother tongue in Haiti, and is spoken by virtually the entire population, yet French remains the principal written language. The film argues that, in an example of history being written by the losers, this violent imposition of the French language has made the truth of Haiti’s emancipation inaccessible to the majority of the country’s population.

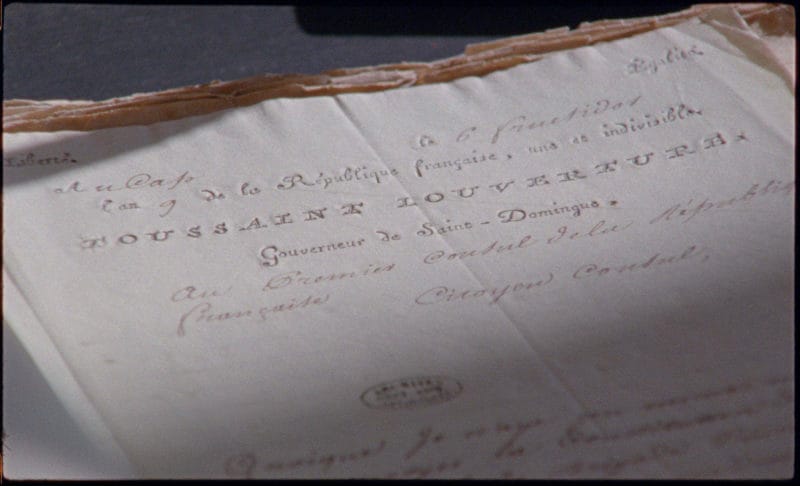

After observing his handwritten memoirs in the French National Archives, Ouvertures follows the ghost of Toussaint L’Ouverture, a leader in the Haitian Revolution, as he travels from the prison cell in the Jura mountains where he spent his final days to present-day Haiti. There he encounters the Living and the Dead Ensemble as they attempt to “creolize” Monsieur Toussaint, Édouard Glissant’s 1961 play about his death. Combining footage of their rehearsals with images of locations in Port-au-Prince where the revolution took place, the film is a powerful example of self-emancipation through translation.

As a filmmaker whose work has consistently investigated the connection between colonialism, capitalism, and history, Henderson is acutely aware of his presence as a white European artist working in the Caribbean. Guided by an ethical drive to make a film about Haiti told by Haitians, he films his actors with a detached yet inquisitive style. It prompts the feeling that the camera has been commandeered by L’Ouverture’s ghost, who watches in amazement as the group workshops a series of improvised scenes and slam poetry battles. Creating an arena in which the history of the revolution can be publicly refigured, each contested line of Glissant’s play goes some way toward filtering out the colonial mindset that persists through language. This process creates a chorus of different voices and perspectives, demonstrating that translation is not just an intellectual exercise for expressing meaning, but also a political act that enables the free flow of ideas. A critique of the methods through which history is taught and learnt, these films intelligently unpack how the residue of imperialism has prevented Haiti and other former colonies from realizing the emancipatory promise of their historic uprisings.

The London Film Festival ran October 2 through October 13.