Alexander Calder (1943), gelatin silver print (photo by Arnold Newman, image via Regan Vercruysse on Flickr)

Just like the mobile sculptures he famously pioneered, a young Alexander Calder couldn’t stay in one place for very long. Calder and movement were synonymous, a predictable pattern for this 20th-century sculptor who was born in Philadelphia, raised in California, and went to college in Hoboken, New Jersey — all before deciding to become an artist. Once Calder did decide to pursue art, he spent his critical early years pivoting between New York and France. And when back in Manhattan he rarely retained the same address for more than a year, migrating from one cheap bachelor pad to the next (and so on, on repeat, even after he was a family man).

As a result, diehard Calder fans may be disappointed to learn that there are too many places in the city to pin down and mark with a plaque saying Calder slept or ate or studied or sketched or exhibited here. The first comprehensive biography of the artist, Calder: The Conquest of Time: The Early Years: 1898–1940 (Knopf, 2017) written by art critic Jed Perl, provides a helpful narrative map (and will soon be followed by a second and final biographical volume, Calder: The Conquest of Space: The Later Years: 1940-1976 in 2020).

Today, on the anniversary of the artist’s death, we chart a few New York spots that were meaningful to Calder — from Greenwich Village to the Upper East Side (when it was still called Germantown), and some zip codes in between.

111 East 10 Street

It’s unclear which of the apartments in this row of mid-19th century townhouses (maybe even this one currently on the market) was home to Calder and his parents, but he lived in one of the building’s 29 units at a crucial moment in his life. The mustachioed 25-year-old had just decided to abandon a fiscally responsible engineering career and pursue art studies, instead. Calder lived on this leafy East Village block for a little under a year in 1923, commuting uptown to classes at the Art Students League.

Art Students League, New York (photo by Jim Henderson/Wikimedia Commons)

Art Students League, 215 West 57th Street

Calder was enrolled at the Art Students League for around 16 months beginning in the fall of 1923. “This is a very critical time for Sandy,” Calder’s mother wrote at the time in a letter to his sister. “I wonder often what will happen.” Despite being raised by two artist parents, this landmark French Renaissance-style building was where he received his first formal art training. Some faculty members were family friends, and Calder was older than the average student (factors that contributed to his aversion to following instruction). Among Calder’s teachers was John Sloan, a co-founder of the Ashcan School.

11 East 14th Street

During the summer of 1924, after completing a full academic year at the League, Calder moved into his first solo New York apartment — a studio just off Union Square Park at 11 East 14th Street, previously used by his father for sculpting. His parents had left Manhattan to spend a few months in Europe; Calder was a bachelor on his own in New York. “Am really enjoying this studio life,” he wrote his sister right after their parents left town. “Don’t make the bed, seldom eat (I weight [sic] 160, str.), have 2 easels, 3 stands, 2 tables, + the floor just littered with junk.”

Berenice Abbott, “Provincetown Playhouse, 133 MacDougal Street, Manhattan” (1936), photograph (image via New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Provincetown Playhouse, 133 MacDougal Street

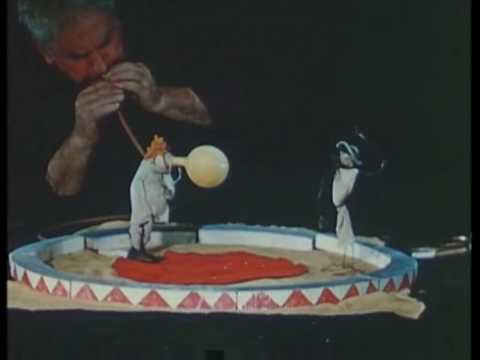

One of Calder’s gigs during his art student phase was working as a stagehand at Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village, then a major experimental theater where Eugene O’Neill often staged his freshly written plays. Calder described the place in a letter to his sister as “a very tiny theater, a converted barn,” and spent his time there moving scenery around between acts — an experience he’d remember later when creating theatrical works like his “Cirque Calder (Calder’s Circus).”

142 West 10 Street

Still wandering nomadically in his first couple years in New York, for part of 1925 Calder rented a room in the apartment of married couple Alexander Brook and Peggy Bacon (both artists). The twenty-something made himself at home there, befriending the pair’s two kids and joining in on bohemian parties hosted in the living room. Brook was a helpful contact for Calder, since he was assistant director of the nearby Whitney Studio Club (the original iteration of what is now the Whitney Museum of American Art).

William M. Van der Weyde, “Hippopotamus, Central Park Zoo, N. Y. City” (1906), tinted collotype printed on postcard (image via New York Public Library Digital Collections)

Central Park Zoo

Calder loved visiting the Central Park Zoo so much that he crafted a special carrying case to hold his paper, ink, brushes, and other supplies on his frequent sketching trips there in the mid-1920s. At the zoo, he created hundreds of drawings of the resident creatures, many of which appeared in his first published book, Animal Sketching (1926). “Animals – Action,” Calder wrote in the book, “these two words go hand in hand in art.” Animals, always on the move, were a favorite subject of the kinetic-sculpting artist.

46 Charles Street

Calder left New York for Paris in 1926, but returned during the fall of 1927 with a suitcase full of eight-inch tall, wire-sculpted circus characters that he made overseas (now “Calder’s Circus” at the Whitney Museum). After crashing at his parents’ apartment first, he soon rented a room at 46 Charles Street and gave live circus performances there with his cast of miniature elephants and acrobats, starring himself as ringmaster. (Calder often charged an admission fee to such performances, which may have helped pay the rent.)

Mabel Dwight, “Greetings from the House of Weyhe” (1928), lithograph (image courtesy of the McNay Art Museum, gift of Janet and Joe Westheimer)

Weyhe Gallery and Bookshop, 794 Lexington Avenue

While back in New York, Calder also arranged for a two-person exhibition at the Weyhe Gallery (a combination gallery and bookshop) alongside painter Emile Ganso. The young artist would always think of this show, which ran from February to March of 1928 and exhibited his early wire sculptures, as his first important exhibition. Calder’s mother brought flowers to the opening, and allegedly declared: “Something will come out of all this, though it is not our style, something will come of it.” Only two or three works sold during the show (including a sculpted portrait of Josephine Baker), but Calder mainly benefited from lots of press attention.

45 West 11th Street

A 30-year-old Calder first spotted Louisa James at the beginning of an ocean liner voyage transporting them both from Paris to New York in June 1929. By the time the ship docked in Manhattan, they were an item. During their New York courtship, James (who would become Calder’s wife of 45 years) likely lived in a rented apartment at 45 West 11th Street. By November of 1930, she’d decided to marry the artist, writing to her mother (perhaps from this building) that “he appreciates and enjoys the things in life that most people haven’t the sense to notice … He has tremendous originality, imagination, and humor which appeal to me very much and which make life colorful and worthwhile.” The couple were married in January 1931; Louisa’s golden engagement ring was a Calder original, with a spiral on top.

Fuller Building (image via Wikimedia Commons)

Pierre Matisse Gallery in the Fuller Building, 41 East 57th Street

Calder and Pierre Matisse had some things in common: they were both sons of big-name artists, roughly the same age, and frequently traveled the New York–Paris circuit. When Calder was looking for a New York gallery in the 1930s, he began courting Matisse (who usually exhibited European artists, but made an exception for this persistent American). The gallerist hosted three solo Calder exhibitions between 1934 and 1938, but occasionally got irritated with the sculptor. After Calder’s first exhibition, when summer renovations were about to begin in the Fuller Building, Matisse exasperatedly wrote to the artist that “you better come quick to get your ‘objects Calderiens’ if you don’t want to find just a bundle of wire mixed up with some plaster blocks!!!”

244 East 86th Street

Alexander and Louisa Calder and their young daughter, Sandra, lived in a series of Upper East Side apartments during the mid-1930s, the first of which was at 244 East 86th Street. The artist also worked in the same inexpensive neighborhood (then called Germantown), converting cheap storefronts into makeshift studios. The Calders had bought a run-down colonial house in Roxbury, Connecticut in 1933 — a home that would ultimately become their permanent residence and is still owned by the family — but it wasn’t winter-proofed yet so they spent colder months in New York.

Calder spent time off and on in Manhattan until the 1940s, but after renovations were complete on his Connecticut fixer-upper he lived there year-round. The energy in the countryside may have been slower-paced, but the sprawling space allowed him to create bigger and bigger sculptures than the miniature wire pieces he crafted in the city during his youth.