An Exhibition Across Los Angeles Takes on New Meanings in Times of Protest

When We Are Here / Here We Are opened in mid-May, the street landscape of Los Angeles looked decidedly different.

LOS ANGELES — When the collective Durden and Ray presented We Are Here / Here We Are on May 16, the street landscape of Los Angeles looked decidedly different than it has in the weeks since the killing of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. Empty of traffic (and not yet full of protesters), the world felt surreal enough with only a global pandemic at the forefront of our minds. Still, even without the knowledge of what was to come, the strangeness of the lack of cars in a city almost defined by them makes an eerily calm setting for the exhibition’s diverse collection of artworks.

Gathered together under the premise of “our innate desire for connectivity through sensation,” some of the artworks on display reflect just that. Andrew Phillip Cortes’s “Para el Barrio (For the Neighborhood)” (2020), for instance, takes a defunct Payphone, a form of telecommunication some may be surprised to learn is still in active use, and covers it with a tactile mosaic of glass, mirror, and paint. Cortes points to our collective ability to transmute the aesthetics of our communal environment — beautifying it for own sakes.

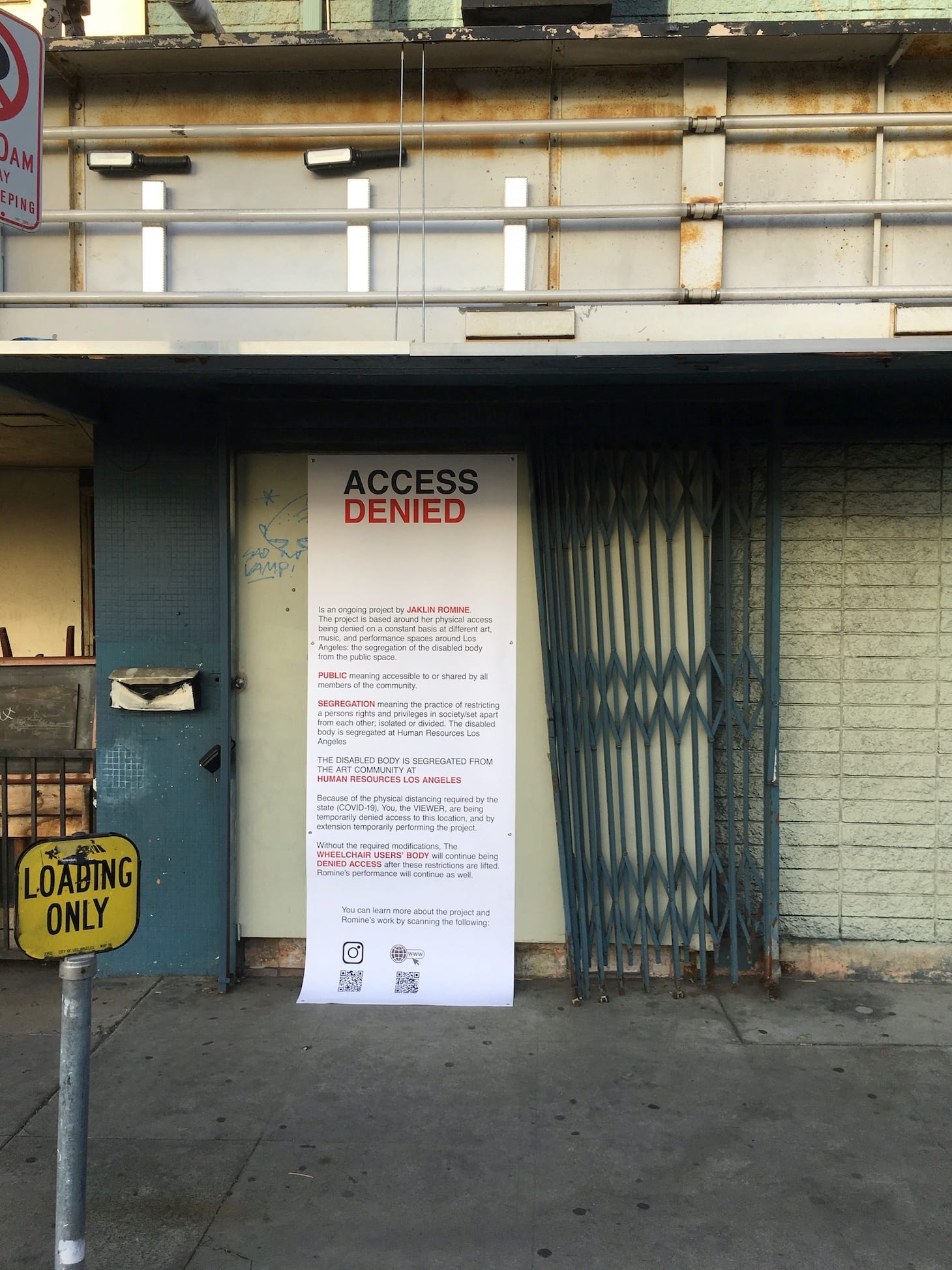

Another artist, Jaklin Romine, uses the stay-at-home orders as a backdrop to reflect on the everyday reality of disabled people in her ongoing performance piece ACCESS DENIED. For the piece, Romine charts multiple art world locations she cannot go to because of their inaccessibility to wheelchair users like herself and invites viewers to visit these locales. In doing so, the viewer becomes part of the artwork in the sense that they are, albeit temporarily, also denied access to them, acting as a proxy for Romine’s experience as they use their own bodies as an extension of hers.

Other artworks have adapted in reaction to the protests of police brutality and systemic racism. Brenna and Nancy Ivanhoe’s “behind under around” (2020) showcases a vivid collection of paintings both discrete from and incorporated into the home’s architecture that reflect the beauty of the surrounding garden. Normally this would present as a relatively apolitical artwork save for the fact that the artists have added a “Black Lives Matter” sign to the yard, voicing their support.

Further east, Makenzie Goodman and Adam Stacey’s “A Shrine to the Old West” is almost indistinguishable from the actual trash that surrounds it, a loaded context for the framed portrait of John Wayne that serves as the piece’s centerpiece. Wayne, an icon of American masculinity, Western expansion, and old Hollywood, famously stated his alliance with white supremacist ideology in a 1971 Playboy interview. The “fallen shrine” begs the question: Is Wayne and the ideologies he represents reflected upon with nostalgia or condemnation in the hearts and minds of American citizens? If our current state of policing and protest is any indication, it seems the answer is both.

We Are Here / Here We Are continues through Saturday, June 20 (dawn to dusk every day, unless otherwise noted) at various locations around Los Angeles County.