Shellyne Rodriguez’s Drawings Expand the Definition of “Essential Workers”

"I didn't want to be pigeonholed into that idea, the 'COVID drawings.’ To me this was just part of a moment,’” she told Hyperallergic of her drawings depicting her fellow organizers and Bronx community.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit New York, artist Shellyne Rodriguez was emerging from a very different battlefield. In February, she had helped organize FTP3 — the third in a series of actions protesting police intervention in the city’s subway system, led by activist groups Take Back the Bronx, Decolonize This Place (DTP), Why Accountability, and others. By mid-March, a shelter in place order had been imposed in the city, and Rodriguez, like many New Yorkers, hunkered down at her home and studio.

“People were like, ‘How are you even able to make work right now?’ Well, it’s partly because dystopia is always my reality as a political organizer,” Rodriguez said in an interview with Hyperallergic. “For me, it was an opportunity to archive. And there was this sense of urgency to make as much as I could before I was pulled into the street again.”

During the months of lockdown, the Bronx-based artist created 15 drawings and five paintings depicting her fellow community organizers and the essential workers around her, fueled by a drive she describes as core to her artistic project: archiving disappearing spaces and people under threat of displacement.

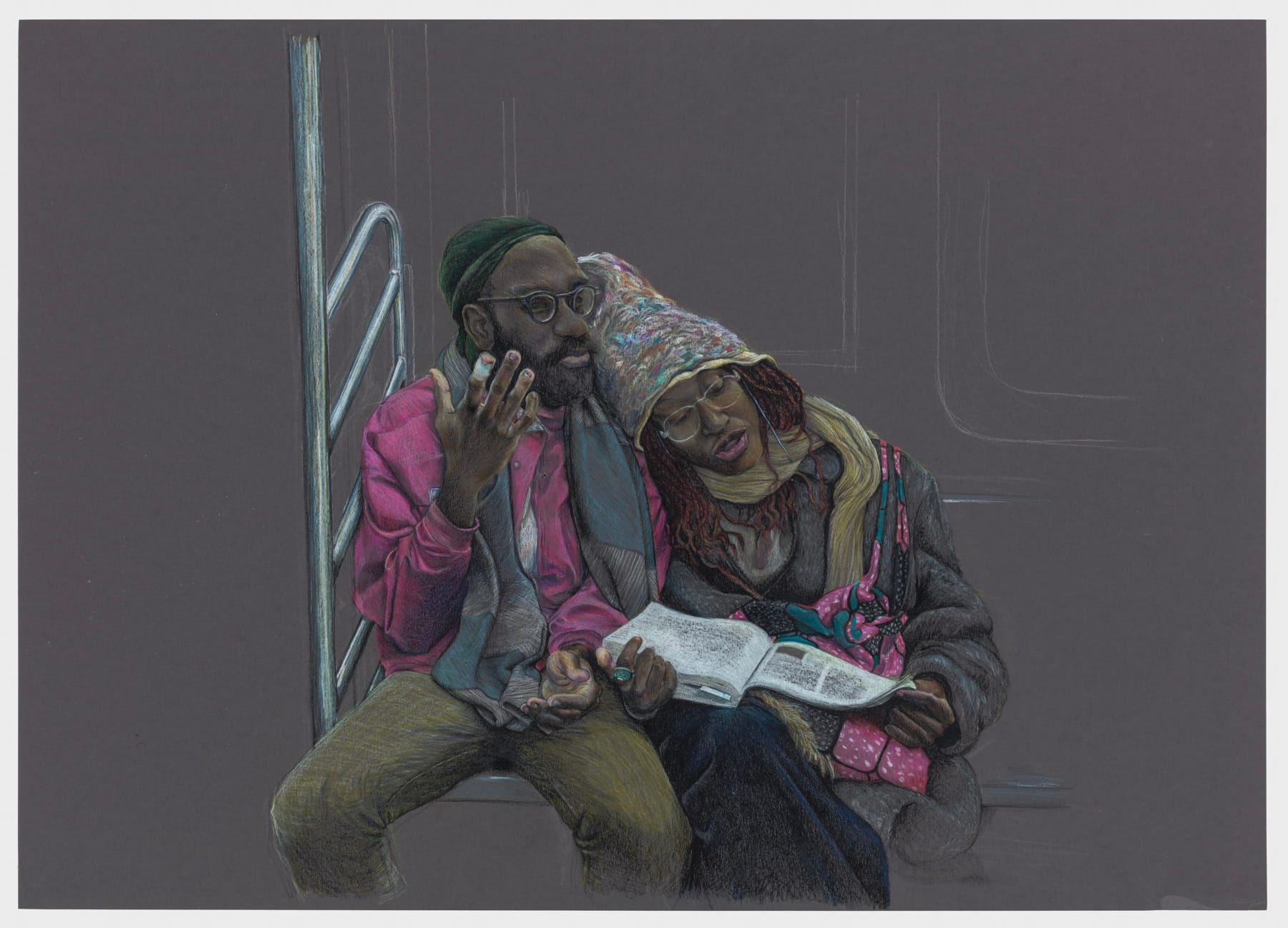

One of her first drawings was “The Debrief,” depicting her two colleagues, Tre and Dalaeja, returning from a meeting to discuss the failures and successes of their last action. The figures, rendered in painstaking detail in colored pencil against dark paper, seem to emerge from their surroundings as though from a fog. The ghostly outlines of a subway car convey a sense of place, but the focus and specificity is distinctly placed on the figures.

“I’m a former MoMA Educator, and at the museum, I was always looking at all these Austrian painters, [Egon] Schiele, and artists who were working and documenting their friends,” Rodriguez said. “Even Picasso was documenting people who died in concentration camps, doing wartime documenting of the intellectuals and the thinkers and the movers and the agitators. I was reflecting on the people — on the collaborators and the times that we’ve broke bread together.”

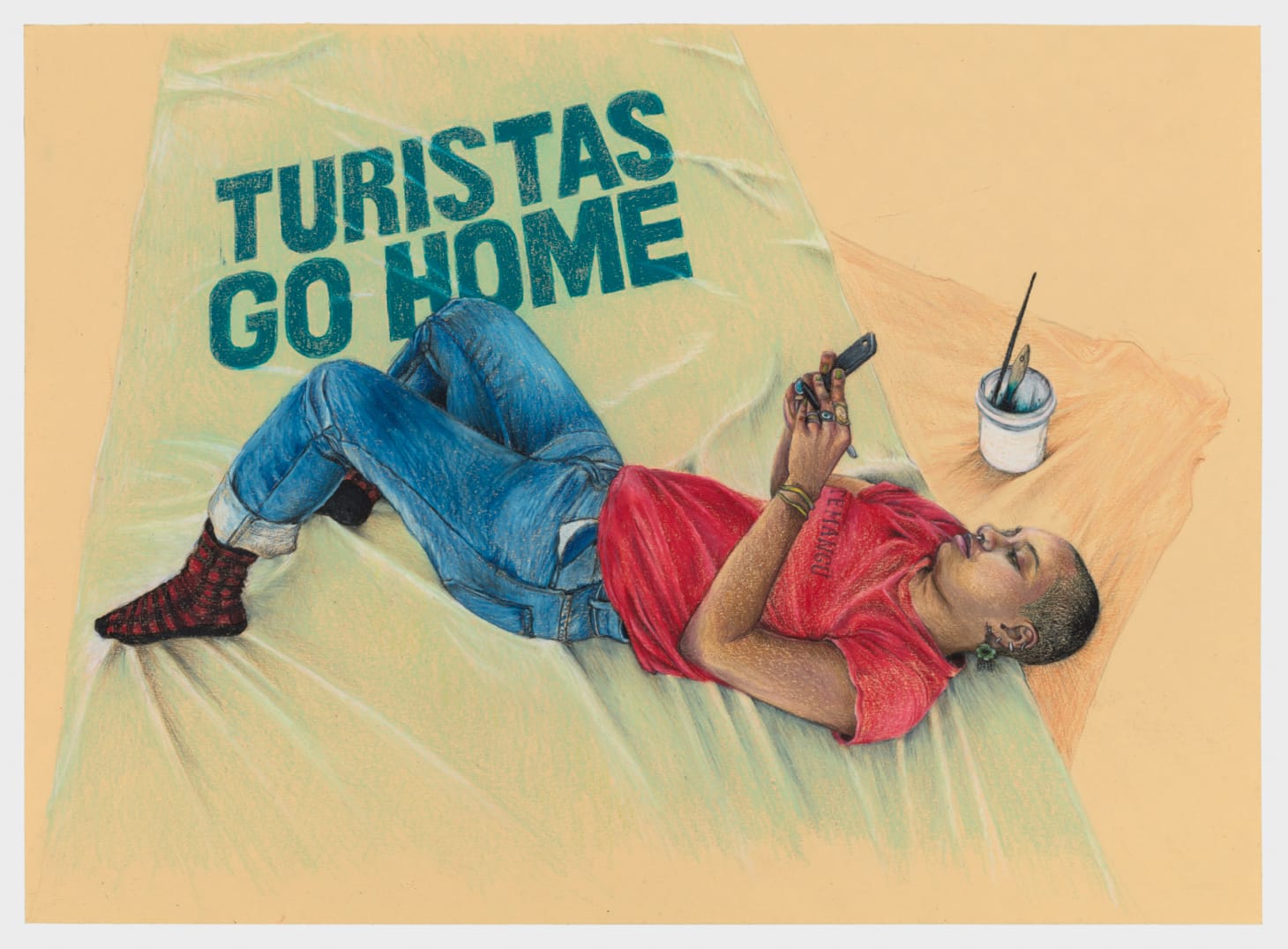

In “Hillary Paints a Banner,” one of her colleagues takes a break from painting what would become a 40-foot-long banner used during the FTP3 protests. The text reads “turistas go home,” a cheeky reference in opposition to the popularization of a step street in the Bronx, which became a tourist draw when the film The Joker was released. During FTP3, Rodriguez says, they marched from the local courthouse, where people pay their fare evasion summonses for jumping over the train turnstiles, to the so-called “Joker stairs.”

The FTP protests were born out of the rage and horror spurred when police on the NYC subway drew their guns on Adrian Napier, an unarmed Black 19-year-old, after he hopped a turnstile last year.

“The spirit behind launching the FTPs was an angry auntie spirit — it was Black women, who were like mothers,” Rodriguez said. “Cuomo declared they’re going to put 500 new cops in the MTA and immediately our kids are getting beat up and getting guns pulled on them. You’re criminalizing the poor. And that means our babies, Black teenage males, first and foremost. ‘Hilary paints a Banner’ was just thinking about the labor that went into all of the ruckus we caused in New York.”

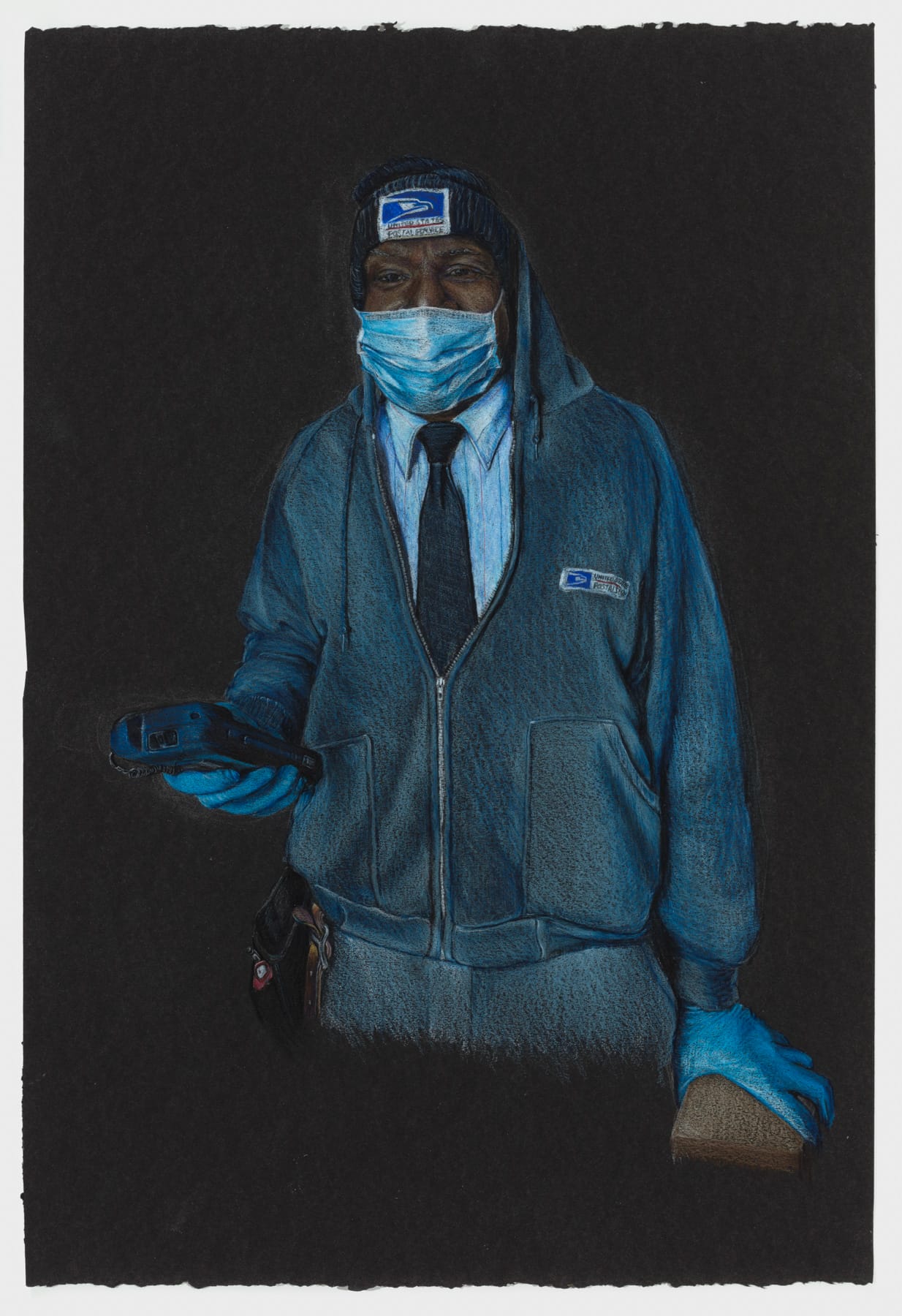

Eventually, Rodriguez turned her pencils to the people immediately around her, a limited group that included her building’s super, Dragan, and her mailman, Andy. The latter dons the light blue surgical mask and gloves that have become somber symbols of the pandemic, nearly camouflaged by his head-to-toe navy USPS uniform. Only Andy’s eyes are visible, revealing the candid but weary stare of one of the many workers who could not stay home, facing daunting risks as the virus continued to spread.

Still, Rodriguez was wary of falling into the trope of the “essential worker” portraits that she began to see everywhere.

“I didn’t want to be pigeonholed into that idea, the ‘COVID drawings.’ To me this was just part of a moment,'” she said. “I did a diptych of two bikers I saw outside in front of the bodega. But even the kid, he’s adjusting his mask. You’ve got to kind of look for it, it’s not in your face. Here is a kid from my neighborhood, and he happened to be wearing this mask because this is COVID 2020. I wanted it to be part of the story, but not the story.”

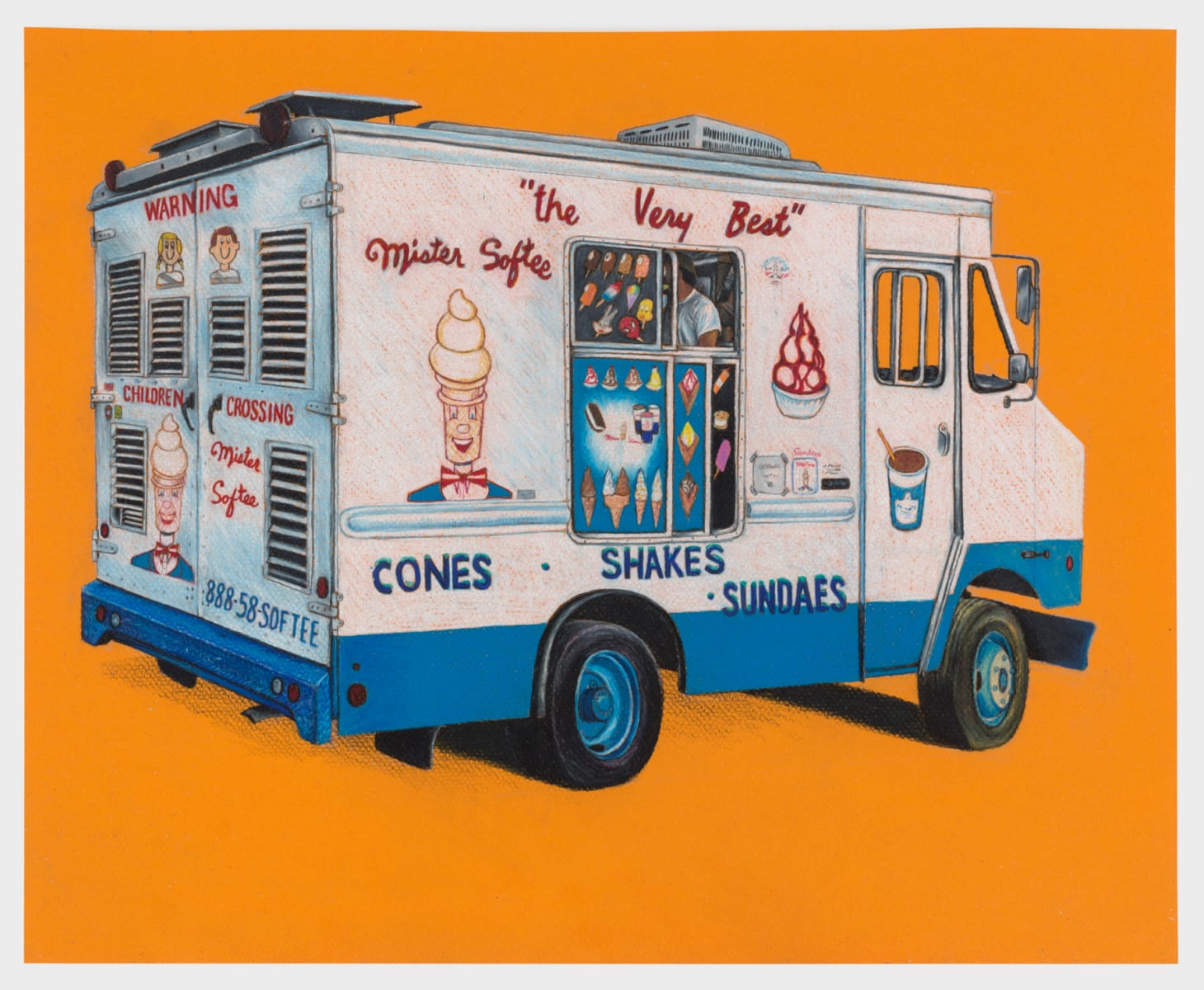

When restrictions began to loosen, Rodriguez made the last drawing of her lockdown series: “Mr. Softee,” a comparatively sanguine rendering of an unmistakable blue and white ice cream truck on bright yellow paper. “Summer came, it got hot, and the truck was out, you heard the music. I finished it the same week that Minnesota popped off,” said Rodriguez, citing the Minneapolis protests demanding justice for George Floyd and other Black victims of police violence that ignited demonstrations across the country.

“We had already been planning FTP4. I literally finished it and hit the streets,” Rodriguez said.

The colored pencil drawings she produced during this time are rigorous and exact, with intricate attention paid to every fold, shadow; the medium, she says, allows her to “indulge her meticulousness.” With painting, however, she seeks looser, more expressive passages exemplified by two portraits of community organizers, painted from life in her apartment and finished during quarantine: “Najieb Sits by the Door (After Grace Campbell)” and “Lisa Ortega Rolls the 4,5,6 (Ceelo).”

“I respect painting immensely. I look at Henry Taylor, I look at Alice Neel, and I wanna cry, the way they can lay a mark down,” Rodriguez said. In both works, the artist layered paint richly to build up the thick architectural molding on the walls of her apartment, yielding a visual discord between the sitters — radical activists, women of color — and their surroundings.

The title of Najieb’s portrait refers to Grace P. Campbell, the first African American woman to run for state office in New York and become a member of the Communist Party; and to The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1969), a novel by Sam Greenlee that tells the fictional story of the first Black CIA agent, who leaves the profession to train Black militants.

“There’s all these coded things in the painting, the way that traditionally portraits have been,” Rodriguez says. “What’s in the portrait? What’s this still life? Why the skull, why this, why that?”

Though she laments that political art and artists are often talked about “with little nuance,” Rodriguez recognizes that her activism and her artistic practice are intertwined. “I usually like a really strict line between my practice and my political work, but I know it comes from my subjectivity, this is who I am,” she said.

“You look at my body of work and it’s always talking about the Bronx, it’s always talking about our subjugation, how we survive. It’s being a geographer to some degree, it’s my built environment.”

The drawings and paintings Rodriguez pursued during the early days of the pandemic pay homage to the people in her intimate organizing circle as well as to those who became part of her daily environment when the world abruptly changed. In different ways, both could be described as “essential.”

Rodriguez recalled the words of Kazembe Balagun, a renowned intellectual from the Bronx. “He told me, ‘Y’all have to archive and document all the work that you’re doing. Black and Brown revolutionaries get forgotten. If you don’t do it, it will be erased,’” she said. “And that stayed with me.”