A Kurdish Artist’s Creative Resistance From Behind Bars

“Politics, war and oppression are a part of my life,” Fatoş İrwen explained of her current solo show, Exceptional Times.

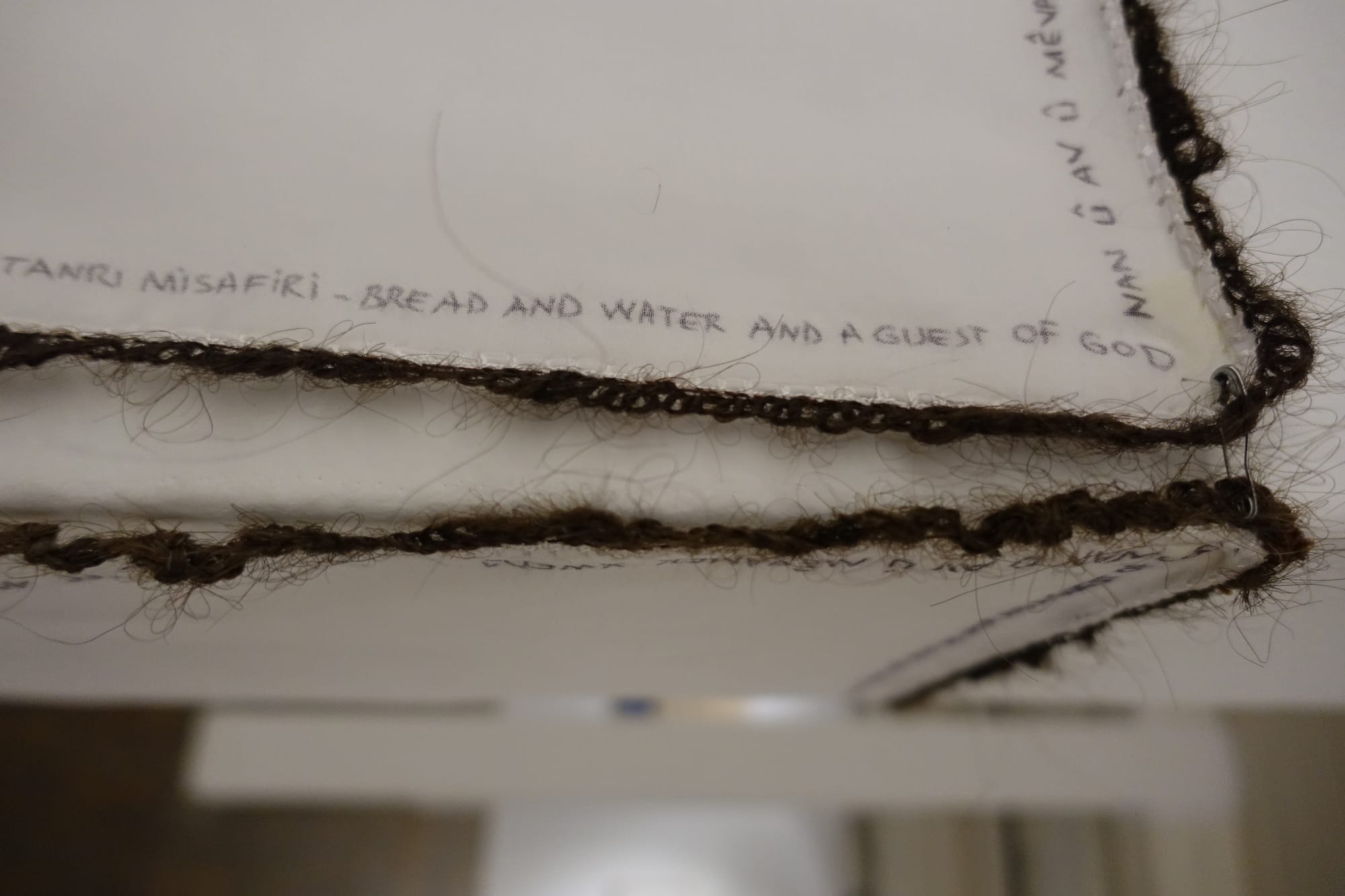

ISTANBUL — The day before she was taken to prison in 2017, Kurdish artist Fatoş İrwen had filmed a performance piece on the narrow backstreets of her home city of Diyarbakır in southeastern Turkey. Wearing a flowing white dress, she acted out fragments of the fraught history of this ancient settlement, which had been recently shattered by conflict. Behind bars, İrwen continued that performance, by embellishing the dress she had worn that day with thread made from her own hair and that of other female inmates

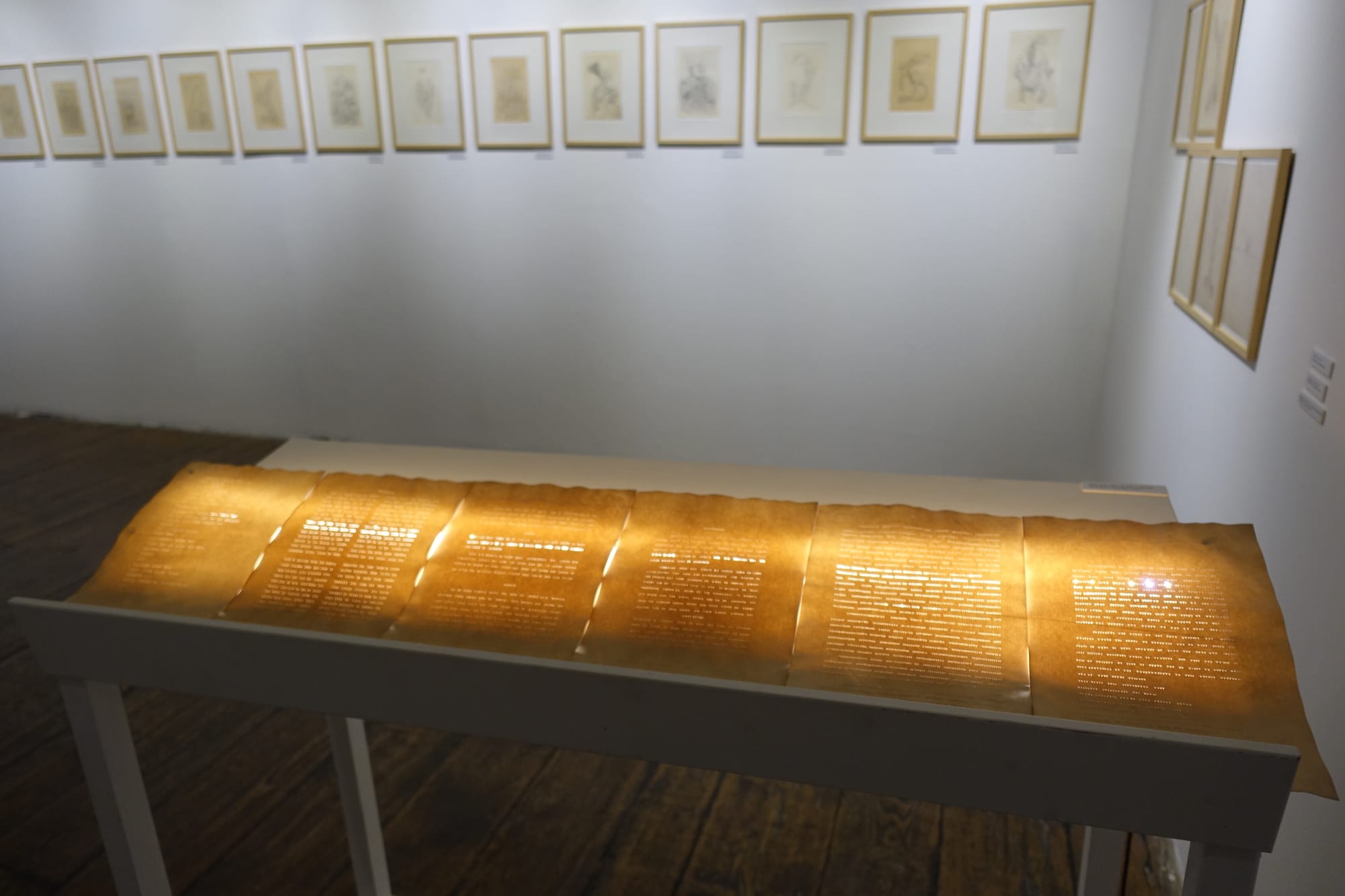

Both dress and film are now displayed as part of the artist’s first solo exhibition, Exceptional Times, which runs through June 27 at two independent Istanbul venues, cultural center Depo and art gallery Karşı Sanat.

The show’s drawings, paintings, textile pieces, photographs, installations, and sculptures span more than a decade of İrwen’s career, including the nearly three years she spent in prison. She was prosecuted with little evidence under broad “anti-terrorism” laws often used to target Turkey’s Kurdish minority and others seen as part of the opposition — including Depo’s jailed founder, philanthropist Osman Kavala.

The works in Exceptional Times demonstrate the artist’s prolonged engagement with the politics of physical and social spaces, reflected through the lens of her experiences as a woman and a Kurd. “Politics, war and oppression are a part of my life,” İrwen told Hyperallergic on a tour of the exhibition.

The show’s title is drawn from a 2010 performance piece, one of the artist’s many works utilizing hair and the human body as both subject and medium. But in its original Turkish (Olağan Zamanın Dışında), it has inescapable resonances to the “state of emergency” (olağanüstü hâl) legislations that have repeatedly been employed to restrict freedoms, including creative ones, in the Kurdish-dominated southeast region and beyond. For Kurdish artists like İrwen and Zehra Doğan, who was also imprisoned on “terrorism”-related charges, the current pressure on dissenting voices in Turkey is more the norm than a sign of exceptional times.

While in prison, İrwen says she made 1,500 artworks using hair, tea, food, shoe polish, old textbooks and newspapers, bed sheets, laundry pegs, scarves, and even mold and cigarette ashes. “These works are reacting to the materials and to the system; not surrendering to them, but transforming them,” noted exhibition co-curator Mahmut Wenda Koyuncu.

Pointing at a cluster of orbs scattered on the floor at Depo, İrwen explains that she crafted them from the hair of fellow inmates who were on hunger strike, including Kurdish politician Leyla Güven. The 2019 piece is titled “Gülleler” (Cannonballs). “The hunger strike was like firing a shot to the outside world,” İrwen says.

Life and death, growth and decay intertwine in many of İrwen’s works, including “Beton Bahçe” (Concrete Garden, 2019–2020). In the installation, small cement blocks serve as miniature plinths for objects — dried bugs, flowers, animal bones, tiny trinkets — that İrwen gathered from the prison yard. Among them is the bent spoon with which she scraped paint chips from the ceiling of the prison bathroom. These fragments are displayed as “Zaman Katmanları/Duvarlar” (Time Layers/Walls, 2019), an “archaeological excavation” into the building’s past.

Kurdish activists have pressed unsuccessfully for the infamous facility — where many political prisoners were incarcerated and tortured after Turkey’s 1980 military coup — to be closed and converted into a human-rights museum. But İrwen creates new sites of memory through works like “Zaman Katmanları/Duvarlar,” “Beton Bahçe” and “Hassas Zemin” (Sensitive Ground, 2019), a set of highly personal maps of the prison stitched onto produce packaging material. Other pieces in the exhibition allude to the idea of resistance through writing alternative histories for those who have suffered silencing, censorship, destruction, and omission from official narratives.

“You can’t look at Fatoş’s pieces and say, oh, how sad,” says Koyuncu. “There is no hopeless quality to her work.”

Exceptional Times has been extended through July 10 at Depo (Lüleci Hendek Cad. No:12, Beyoğlu, Istanbul) and Karşı Sanat (İstiklal Cad. Aznavur Pasajı No:108, Beyoğlu, Istanbul). The exhibition was curated by Ezgi Bakçay and Mahmut Wenda Koyuncu.