Guns, Badasses, and Art

Why is the right to buy a gun so profound? Maybe because it's really about the right to be a badass. Black Power, a provocative show up for just six days at the Superchief Gallery at Culturefix, probes the connections between guns, badass characters, and race. With the gun-control conversation ragin

Why is the right to buy a gun so profound? Maybe because it’s really about the right to be a badass. Black Power, a provocative show up for just six days at the Superchief Gallery at Culturefix, probes the connections between guns, badass characters, and race. With the gun-control conversation raging this week, there couldn’t have been a better time for this exhibition.

One of the most potent works in the show is Coby Kennedy’s “Vending Machine” (2011), which dispenses guns. The tag line on the display-case glass reads, “Building a better future.” The irony hits home, given how many folks think spending 500 bucks on a gun is their best shot (pun intended) at a safer future. Somewhere a financial advisor begged his client to put that money into a 401(k) instead, but he lost the argument because what we want to buy is often not driven by rational thinking. And that’s why the starlet in the machine’s embedded video commercial doesn’t rattle off crime statistics to persuade, but rather jiggles and winks to entice. Doesn’t the strong badass get the hot woman?

So what is the badass? And does he (it is a shamelessly masculine type) differ from the ganster, warrior, cowboy, or superhero? Let’s not get hung up on labels. The nuance that matters is how many men desire to project a strong image, a “don’t fuck with me, or else” attitude. Why? That’s a dissertation. But the vending machine gets at one point: to feel safe about the future, to feel as if you have the power to face down any threat. No one’s waiting around for a lucky bite from a radioactive spider.

The subject of a photographic work by Kennedy, “The Fighting Mullatoe of Fort Greene Hill” (2013), looks ripped from a cyberpunk Matrix-style film. The funky outfit and curvy gun suggest Brooklyn in the future. Generation after generation of teens marvel at powerful weapons in imaginary sci-fi universes, and they carry these schemas into the street. This medley of a dreamy expression, a flower in the hat, and a lethal futuristic weapon illustrates the contradiction between gentleness and violence swirling around in the minds of many inner city youth.

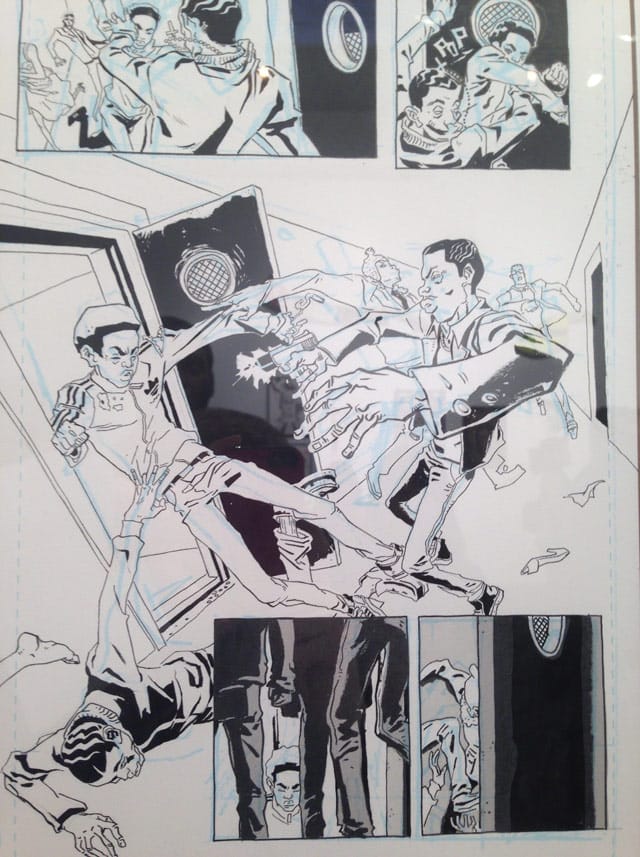

Switching boroughs to Times Square, pages from Ron Wimberly’s graphic novel show men with guns in the heart of the city. In “Sentences (Times Square)” (2007), a muffled gun sits on table with wads of cash in a smoke-filled room. In “Sentences (First Page)” (2007), a man fires his pistol at close range and appears to hit his adversary. There are frenetic lines, wicked elongation, and a dramatic sense of motion animating the scene and giving it a formal punch. In both works, guns serve as emblems and tools to empower their badasses.

In another sculptural work by Kennedy, the viewer encounters guns with American Indian designs on the handles. But reading the titles for the works — “Zip Gun (The Upstart Duke of New Lofts),” “Zip Gun (Prince of Canarsie),” “Zip Gun (Brownsville Brent)

(all 2013) — one reads the names of black neighborhoods in New York. Kennedy is trying to get at the racial politics of guns.

To reduce it to three sentences because you don’t have all day: White men used guns to incrementally take the entire continent away from Native American men. White men used guns to prevent black slaves from revolting on this land taken by force. In moments overlooked by History Channel producers, black and Native American men have wielded firearms to try and take back the power. And this desire to wrest power from the rich white man with a gun now even plays out for many poor white men in America.

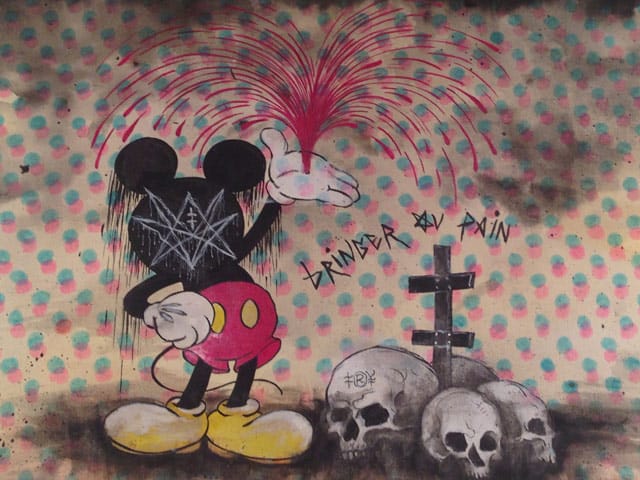

Jorden Haley’s “Bringer ov Pain”(2013) doesn’t feature a gun in it, but the bleeding hand of Mickey Mouse could have been wounded by a gun shot. Haley puts the American icon in black face, which might offend some viewers, but he makes a critical point: overlaying that face with cryptic Wiccan, Masonic, or voodoo signs, he renders a sign of American success as violent, racialized, and enigmatically religious. Only a messy image like this could do justice to the messiness of our country’s past. And as uncomfortable and violent as many of these images are, they hold up a mirror to aspects of American masculinity we’re continually looking away from in the current debate.

Black Power is on view at the Superchief Gallery at Culturefix (9 Clinton Street, Lower East Side) through April 14. There will be a closing party on the last night, including an artists’ talk at 5 pm and a performance by MeccaGodZilla at 8 pm.