How Africa’s Cultural Institutions are Leading the Way in Audience Development and Research

Rather than engaging with Africa’s cultural sector through a singular lens, what if the world looked to it as a source of innovation and instruction?

Over the past decade, a new wave of entrepreneurs has invigorated Africa’s cultural landscape. These visionary entrepreneurs, who represent some of the continent’s best talent in professions ranging from architecture to finance, are creating new models of preserving and showcasing art, history and culture. From Lagos to Luanda, they are building local museums, archives, libraries, arts spaces, and cultural centers. Earlier this year, I launched a network with 25 of them and have seen firsthand how they are redefining what the cultural sector can look like, and what it can achieve in Africa.

While cultural institutions in Africa are making great strides, their contributions are largely overlooked in the global debate about the restitution of African cultural heritage. In the past few weeks, several museums in Europe and the United States have announced their decision to return objects in their collections or take them down from display. Others have shared plans to establish institutional partnerships in Africa, which often lack financial commitments or clear outcomes. As these institutions face a reckoning with their history and practices, an opportunity exists to learn from their African peers. Rather than engaging with Africa’s cultural sector through a singular lens, what if the world looked to it as a source of innovation and instruction?

When Morocco’s Museum of African Contemporary Art Al-Maaden (MACAAL) first opened its doors in 2016, it had a big challenge: to grow a local audience. As one of the first museums in the country dedicated to contemporary art, MACAAL’s team had to figure out a way to transcend class barriers in order to draw a diverse group of Moroccans into the museum. Their solution was a new public program inspired by Morocco’s tradition of sharing a meal of couscous every Friday.

On Fridays, MACAAL began inviting local taxi drivers into its space for a couscous lunch. The taxi drivers soon began to bring their family members, friends and people from all walks of life — from tourists to construction workers. The ripple effects of this tradition have transformed the museum from an exclusive space for elites into one that bridges social and economic divides. In an era where many museums in the West are facing challenges in welcoming diverse audiences, African museums like MACAAL can provide a useful blueprint for other institutions seeking to accomplish the same.

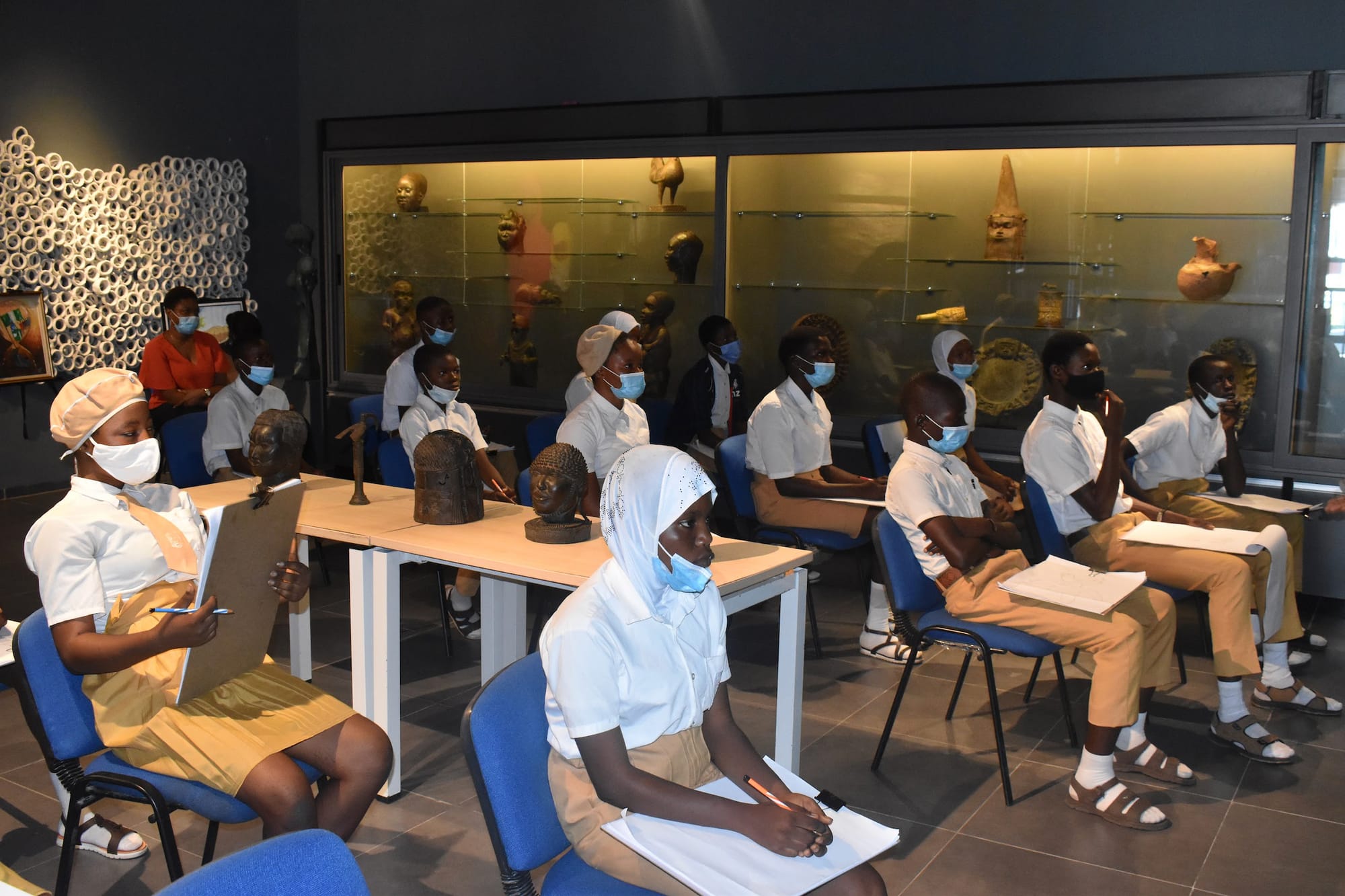

One of the persistent challenges at a museum in the United States where I worked was the low number of visitors, in particular, students. Across the Atlantic in the Republic of Benin, a partnership with local schools developed by the Zinsou Foundation’s Museum of African Art, provides insightful lessons. In 2008, the museum hosted an exhibition of the legendary Malian photographer, Malick Sidibe, which attracted over one million visitors. Most of these visitors were youth. To achieve this at its inception, the museum developed strategies to enable young people from different backgrounds to access the museum.

Through a local partnership with a private school and an oil and gas company, the museum provides free bus rides to students who cannot afford transportation to visit the museum. The museum also enlists the help of popular musicians in Benin, engaging them in a communications campaign oriented towards young people. The museum’s staff regularly go off site to visit local communities rather than waiting for visitors to come through its doors. And, prior to each exhibition opening, the museum hosts an event for school teachers, ensuring that they are served equally alongside art patrons and collectors. With only a small fraction of the budget possessed by many well-established museums, the Zinsou Foundation’s model of partnerships and community engagement is exemplary.

The overarching narrative about Africa’s cultural institutions tends to portray them as in need of know-how and best practices from the West. A story that is less told is how African institutions like the Women’s History Museum of Zambia are taking the lead to share their expertise and knowledge globally. In 2010, the museum’s co-founders, Samba Yonga and Mulenga Kapwepwe, visited the National Museums of World Culture in Sweden where they found missing and incorrect data on Zambian cultural artifacts held in the collections.

Yonga and Kapwepwe subsequently spearheaded a joint collaboration with colleagues in Sweden. This collaboration resulted in the development of a digital heritage platform that provides open data access on Zambian cultural artifacts which were acquired during the colonial period and are presently housed in Swedish museums. As part of this project, the Women’s History Museum has visited local knowledge keepers and elders in communities across Zambia. These engagements have enabled Zambian people to examine some of their oldest artifacts and illuminate the meaning and historical significance that these collections hold. For Swedish museums, this represents an opportunity to expand their learning and professional competencies in analysis, documentation, and storytelling. In order to address the gaps found in the research and scholarship of global museum collections, African-led collaborations such as this one are vital.

Recently, I had the opportunity to meet Paul Ninson, a trailblazing entrepreneur and photographer, who is building the Dikan Center, the first photographic library and archive in Ghana. By skillfully crafting an online fundraising campaign, Ninson succeeded in raising one million dollars last month and collecting 30,000 photographic books to establish the Dikan Center, which is set to physically open in 2022. Paul’s incredible story of creating an institution during a global pandemic demonstrates some of the exciting approaches that Africa’s cultural entrepreneurs are employing despite limited access to resources.

Everyday, as my work with cultural institutions across Africa continues to grow, I am excited by the opportunity we have to amplify their contributions and build a community of partners committed to supporting this work. As more institutions in the West move towards returning cultural property to Africa, I hope that there will be fewer token gestures and more transformation in the way the world understands and engages with Africa’s cultural institutions.