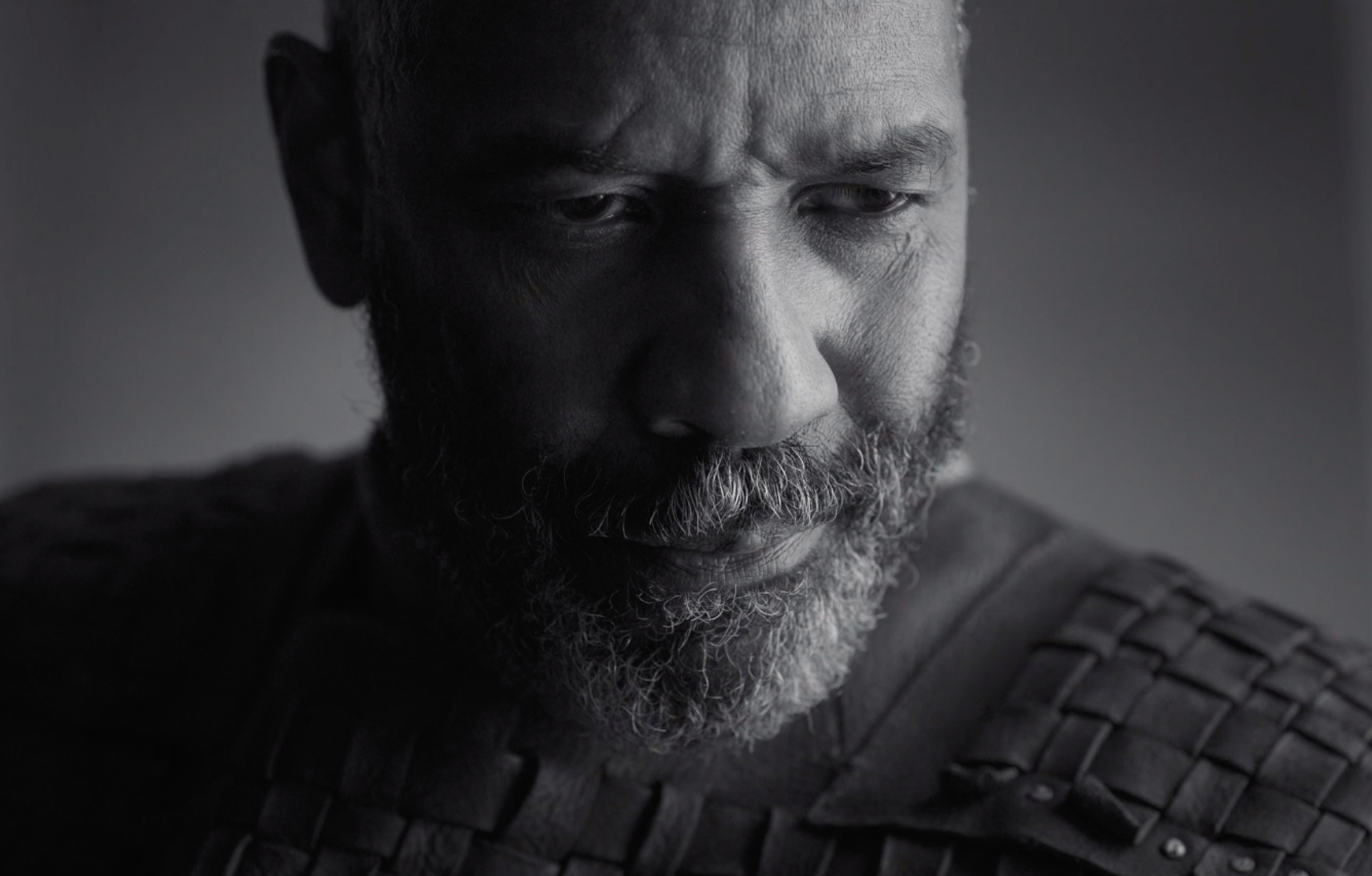

Denzel Washington Stars in a New Black-and-White Macbeth

Working for the first time without his brother Ethan, Coen’s film adaptation, featuring Denzel Washington as Macbeth, embraces the text with unusual faithfulness.

Years ago, This American Life host Ira Glass tweeted that “Shakespeare sucks” because of the supposed lack of stakes or “relatability” in his plays. This came as cultural criticism was beginning to consider “Who is this for?” a more important question than a work’s aesthetic value. But even putting aside how counterproductive it is for critics to treat art like a commodity, the comment irks because it’s plainly untrue. Shakespeare's work is full not just of stakes but also questions of social relations, familial obligation, and free will, along with screeds against materialism and tradition. His characters are among the most multivalent and ambiguous in literature, permitting near-endless interpretive richness. It is a pleasure, then, that Joel Coen (working without his brother Ethan for the first time) has crafted an adaptation of Macbeth that highlights Shakespeare’s achievements rather than the cleverness of its own interpretations. Coen's choices augment the paranoia that permeates the play, but reflect back on the source material rather than overwhelm it.

The most immediately apparent of these choices is the black-and-white cinematography, Dutch angles, high- and low-angle shots, towering shadows, and occasional point-of-view shots to place The Tragedy of Macbeth within the realm of German Expressionism. Heavy fog obscures the very idea of an outdoors in interior shots and self-consciously positions exteriors as isolated soundstages. Macduff’s son is thrown over a railing, presumably to a lower floor, but we see him plunge into such a fog alongside the camera, which emerges somewhere altogether different to begin the next scene. Near the end of the film, Macbeth looks down a staircase at his dead wife’s body, in a shot that inverts an earlier low-angle one wherein he explains away killing the King’s bodyguards.

This is a nifty trick on Coen’s part, linking his Macbeth to a particular cinematic tradition while highlighting the theatrical aspects of the source rather than attempt to make Shakespeare overtly "cinematic." The staging has a similar effect. There is no ghost of Duncan except when the camera is embodying Macbeth’s point of view. There is no cauldron except in the very moment Macbeth seeks out the witches for a second prophecy, and it disappears as soon as he hears what he wants to. There is no grand shot of Birnam Wood approaching Macbeth’s castle that a more self-conscious director hoping to “ventilate” the play might include.

This theatrical approach extends to the performances. Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand play the eponymous couple, joined by a strong supporting cast that contains actors of Irish, English, and American descent, actors Black and white, actors primarily with stage training and actors primarily with screen training, all of whom recite the original dialogue mostly without alteration. The film refuses to make conciliations toward naturalism, realism, or internal coherence by asking the performers to curb their accents or naturalize their speech. On the contrary, Washington and McDormand frequently seem to be playing to the rafters rather than the camera.

So heavily adapted and familiar is Macbeth that it is tempting to reduce any version to a catalog of choices. How are the witches realized? How is Ross personified? What kind of relationship do Macbeth and Lady Macbeth have? Directors of filmed adaptations must decide how to treat soliloquies. All these decisions have interpretive consequences, and Coen has given a great deal of thought to them. But the general familiarity with the play, along with previous filmic adaptations by the likes of Kurosawa, Polanski, and Welles, make it easy to overlook the text. The Tragedy of Macbeth reminds us that the play is not merely a lexical marvel with few equals, but also one of the crowning achievements of Western literature.

The Tragedy of Macbeth opens in theaters December 25.