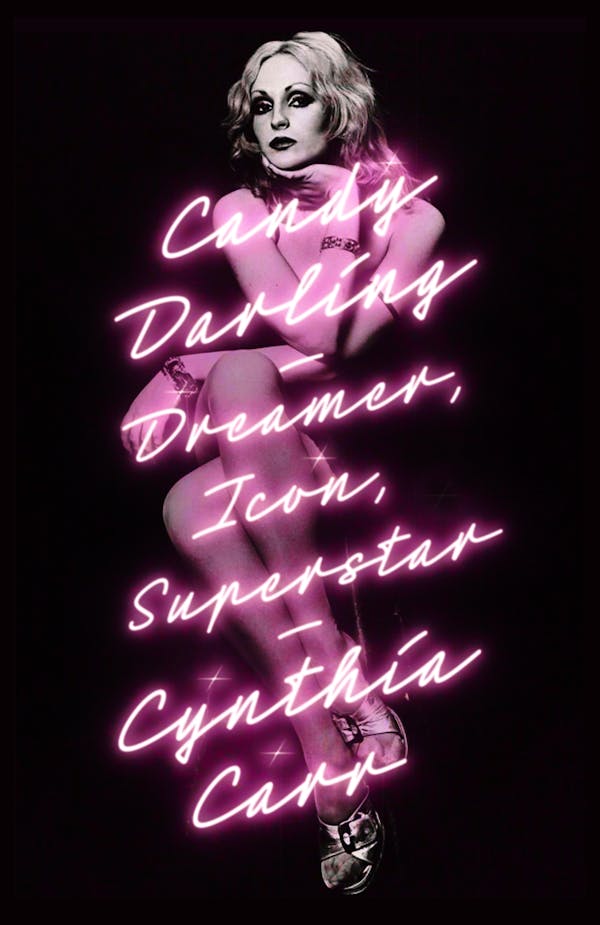

Trans Actress Candy Darling Gets the Biography She Deserves

Half a century after the Warhol film star’s death, writer and critic Cynthia Carr brings Darling’s life to light in an empathetic, well-researched new book.

There are a number of haunting moments in the new biography Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar, written by critic and former Village Voice columnist Cynthia Carr. There’s the revelation that Peter Hujar, whose prolific and sensitive documentation of queer New York in the 1970s and ’80s includes a striking image of Darling on what became her deathbed, would die in that very same room 13 years later when the hospital floor was repurposed to care for those with HIV. Carr also reveals that Darling’s funeral was held in the same room of the Campbell Funeral Chapel on the Upper East Side as Judy Garland’s — a Hollywood connection Darling might have appreciated.

But perhaps most striking is a moment that comes early in the book. We learn that in the 1950s actress Christine Jorgensen, one of the most famous trans women of the 20th century, had moved into a house just a 30-minute walk from Darling’s childhood home in Massapequa Park, Long Island. “Candy would make her way over there, then walk back and forth in front of the house hoping to see Jorgensen appear," Carr writes. "But she never did.”

Candy Darling would go on to appear in 10 films, most notably Andy Warhol’s 1971 Women in Revolt (directed by Paul Morrissey), as well as plays by Tennessee Williams, Jackie Curtis, and Tom Eyen. She was the subject of “Walk on the Wild Side” (1972), perhaps Lou Reed's best-known song, and she inspired music and lyrics written by the Rolling Stones. She was photographed not only by Hujar, but also by the likes of Richard Avedon, Laura Rubin, and Francesco Scavullo, and she would be featured on the cover of After Dark magazine, in the pages of Esquire, Women’s Wear Daily, Photoplay, and multiple issues of Interview, among other publications. Despite her death in 1974 at the age of 29, due to lymphoma, her legacy has rippled across multiple generations, influencing artists ranging from Greer Lankton to Anohni to St. Vincent.

But the story that Carr brings to light of a young Darling is so palpable — ensconced in the brutal conformity of Long Island (birthplace of Levittown), quietly hoping to encounter a trans foremother in person, perhaps seeking a bit of Jorgensen’s knowledge and experience in a world where most people refused to acknowledge the possibility of transgender existence, perhaps also hoping for a bit of her stardust (Jorgensen transmuted her extraordinarily public outing into a decades-long career as a performer, public speaker, and activist). But even without meeting her, Jorgensen must have offered some sense that Darling was not alone, that there was a precedent for her existence, and that one could achieve some measure of the fame she coveted.

Given the celebrity Darling did achieve, it’s notable that there hasn’t been a biography until now, 50 years after her passing. There is the 2009 documentary film Beautiful Darling, but it is littered throughout with both casual and vehement transphobia. The heavy influence on the film of Darling’s close friend and unreliable narrator Jeremiah Newton feels overbearing at times, though he does deserve credit for becoming the keeper of her physical archive and ashes when her mother, Theresa Slattery, sought to rid herself of them. He also went on to record countless interviews with people who knew Darling, creating an archive Carr acknowledges as crucial to her work on the book.

Darling herself, as Carr is careful to note, was an unreliable narrator whose obfuscations were widely acknowledged by those in her life, whether they be tall tales about how she'd spent an evening or fabrications about her upbringing. But the author emphasizes that Darling was not only in the position of having to craft her own existence but also of reckoning with the painful contradiction that, more often than not, her fame was attached to the public pigeonholing her as a drag queen or "transvestite," and not as the woman she knew herself to be.

Unlike the documentary, Carr’s biography is extremely well-researched and deeply empathetic. Readers witness the relentless transphobia Darling faced, but also come to understand her fabulations and dissimulations as both coping mechanisms and a refusal to accept the limitations others tried to impose on her. With no home of her own at any point in her adulthood and largely without money, Darling’s existence was precarious, even as she walked into some of New York's toniest parties on the arm of Warhol at the height of his fame.

That said, the fact that she was a lithe White woman who fit within the beauty standards of her time gave her entrée not available to many of her non-White trans contemporaries or those whose bodies don't conform to entrenched and largely unattainable beauty standards. I don’t note this to critique Darling; she used what she had to survive. Instead I raise the point to critique a discriminatory society and, by extension, historical record. This book offers a rich and nuanced portrait of what it took to fly in the face of that society, and to do so with great style and flourish. It’s crucial to have full, compelling portraits of those who broke ground, proving that we can be both flawed and remarkable. And here we learn unquestionably that Darling was a remarkable woman.

Candy Darling: Dreamer, Icon, Superstar by Cynthia Carr (2024) is published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and is available online and through independent booksellers.