A Cold Plunge Into Glenn Ligon’s Blue

New works exemplify a line of inquiry central to the artist’s practice: How might language and color merge to birth figuration?

I became acutely aware of my own body as I stepped into Hauser & Wirth on a particularly frigid afternoon in January and met a blast of that stifling, artificial warmth. Even as I was thawing out, a chill ran through me as I peered at a selection of works on paper by Glenn Ligon. I was swallowed up in the pits of blue.

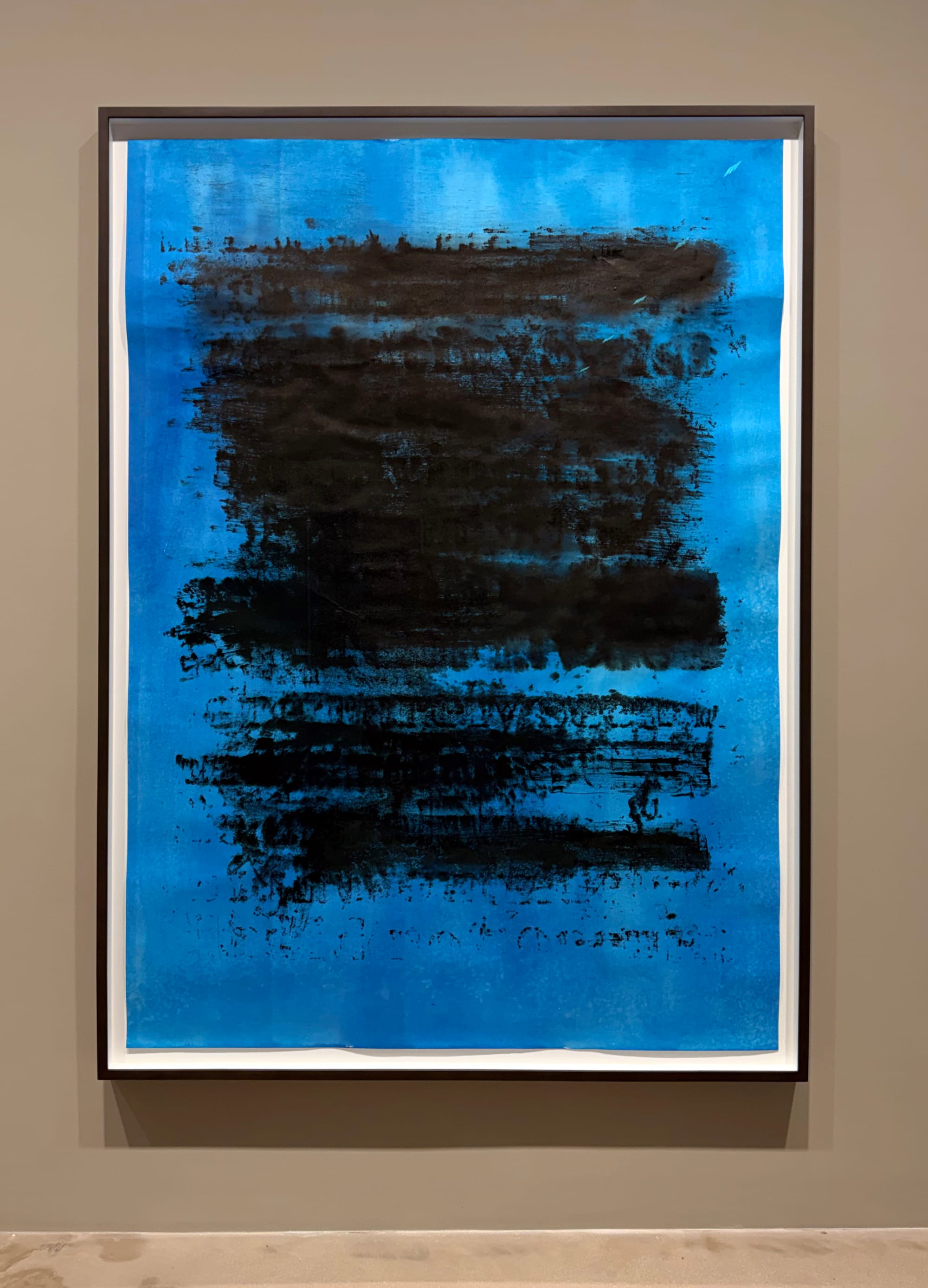

As my gaze cascaded over these resplendent works, I was drawn immediately to “Blue (for JB) #18” (2025). Made of carbon ink and acrylic layered atop a pulp-based torinoko paper, it is almost purely abstract, save for the faint outline of black letters blotting the deep cerulean surface. A mass of a darker cobalt blue unfolds simultaneously across the paper, twisting, turning, and sprouting into a network of black and blue bulbs. Amidst all of this, a singular form emerged. In it, I saw a work by a different artist: the photographer and multimedia artist Lorna Simpson’s “Night Fall” (2023). For a moment, I was convinced that I saw a figure gazing out at me with as much intensity as the central woman lounging in Simpson’s soul-stirring (and intoxicatingly blue) ink and acrylic image.

It is because of this ability to transmute fixed forms into perception-bending experiences for the viewer that Ligon will always be a bit of a magician to me. In his new two-part solo exhibition, Late at night, early in the morning, at noon, the artist quite literally builds on his ongoing engagement with the formal possibilities — and limitations — of abstraction and text, particularly its racialized dimensions. The title of the exhibition is culled from a 1964 introductory text that James Baldwin wrote about an exhibition of Beauford Delaney’s paintings in Paris, particularly a moment where he describes a window through which “everything one saw … was filtered through leaves.”

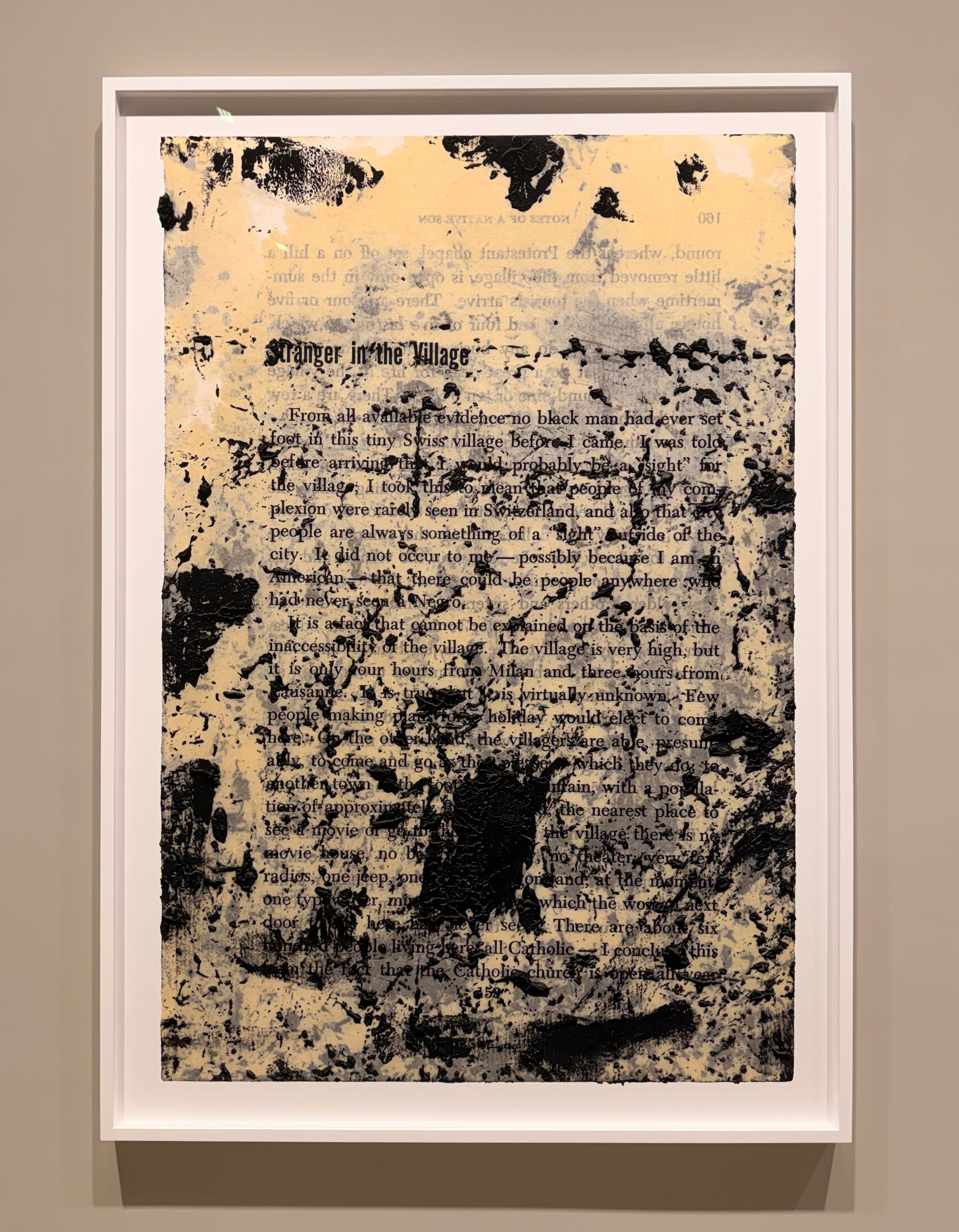

Ligon’s new series of large-scale works on paper, Blue (for JB) (2025), iterates concepts he first explored in his text-based Stranger paintings (1997–ongoing), which reference Baldwin’s 1953 essay “Stranger in the Village.” To create these works, the artist rubs marks onto thin sheets of Japanese kozo paper and layers them onto studies he made for the Stranger paintings. Remnants of Baldwin’s words and shapes are left behind in the process. Then, Ligon augments these rubbings by transforming them into silkscreens on blue surfaces, applying water to them, and letting the ink dance across the paper. These larger works on paper, as well as the 15½-by-12-inch (~39.4 x 30.5 cm) works that make up a series titled Study for Blue (for JB) (2025), exemplify a line of inquiry central to the artist’s practice: How might language and color merge to birth figuration? He seems to suggest that those two elements in tandem create a unique mode of expression that neither alone, nor any other medium, could achieve.

I appreciate Ligon’s decision to grapple with another line from Baldwin’s introduction, in which he writes about light “as blue as the blues when the last light of sun departed.” For me, the moment described in this line becomes less about light and more about darkness — that liminal time when blue is on its way to black. It hints subtly at Ligon’s interrogation beyond color into not only the physical but also the metaphorical interplays of light, dark, and shadow, joining a chorus of discourse surrounding the cultural and formal implications of the colors blue and black. In 2002, David Hammons notably brought viewers into his participatory installation “Concerto in Black and Blue,” which involved viewers casting small blue flashlights against bare walls in complete darkness (read: also blue on black). The resulting work is quasi-sculptural in that it continues to be made and re-made by each new audience. Requiring darkness, as well as active and collective participation, Hammons asserts the value of artwork that evades capture in conventional ways. And in scholar Imani Perry’s 2025 book Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People, she maps an intricate entanglement between the concept of racialized “Blackness” and the color blue.

Ligon's “Blue (for JB) #12” (2025) coaxed me in. I wanted to swim inside its frame, or at least the parts of its surface unmarred by thick layers of black lettering. The type looked as though it had been roughly scrubbed to a point of illegibility, except for a few prominent places. One small point looked to me like the letter “V” peeking out from behind this curtain of chaos. The longer I stared, the more the letter began to resemble an eye, and I experienced a moment of pareidolia — the psychological phenomenon causing humans to see facial features in random patterns. My mind jumped to another work by Simpson, “Howling” (2020), depicting a melting blue landscape ruptured by a tiny sliver through which a woman’s eye looks out. In both works, glimpses of such prominent marks amidst otherwise abstract surfaces lead me to imagine whole figurative worlds layered beneath their surfaces. I felt beckoned to plunge into that icy aqua expanse.

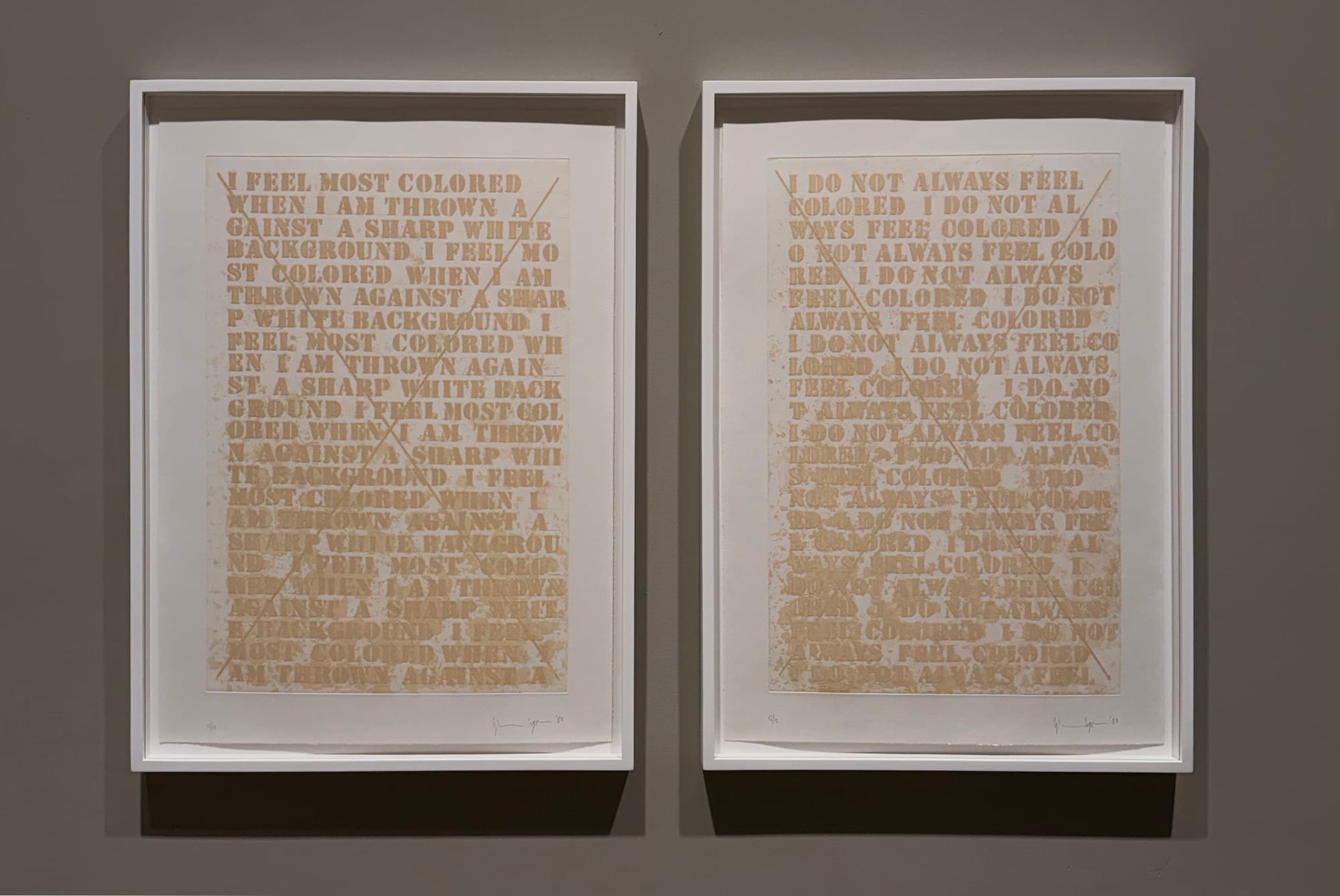

The second part of the exhibition takes place in a separate, smaller gallery and represents a more holistic look back at Ligon’s printmaking practice, spanning the early 1990s until today. In the diptych “Untitled (Cancellation Prints)” (1992 and 2003), color is racialized, with the phrase “I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background” repeating across one of the frames. Both panels in the diptych, however, are “cancelled” out by a thin “X” across their surface. Coupled with the fact that the phrase and letter are both etched in a light cream color — meaning they lack the contrast they allude to — this work further complicates the construct of racialized “color.” Indeed, across all these works, “blue” and “black” seem less descriptive features of physical artworks than their very conceptual canvas.

Glenn Ligon: Late at night, early in the morning, at noon continues at Hauser & Wirth (443 West 18th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through April 11. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.