A Millennia-Long Fascination With Armor

The Worcester Art Museum’s reopening of its armor galleries goes far beyond the romance with medieval Europe.

WORCESTER, Mass. — What can historical armor tell us about the knights of the past? After years of restoration and preparation, visitors to the Worcester Art Museum can now explore the armor galleries, reopened in November of last year. Although there is a fair bit of lore concerned with chivalry and round tables, this armor exhibition goes far beyond the problematic romantic notion of the white knights of medieval Europe. By collectively presenting armor donned by everyone from hoplites to samurai to Sudanese soldiers, the galleries make an important argument for the global appreciation of these wearable pieces of art.

Why do certain museums in North America have so much armor in their collections? Armor collecting was quite the hobby of Gilded Age collectors and businessmen like William Randolph Hearst and Clarence H. Mackay. These wealthy men and their foundations donated much of their extensive collections to places like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City or the Detroit Institute of Arts. The former, for instance, currently holds the largest collection of arms and armor in the nation, with a staggering 14,000 objects. But what is less well known is that the second-largest armor collection in the United States resides not at the Getty or the Art Institute of Chicago, but within the Worcester Art Museum (WAM) in Massachusetts.

The heart of the WAM’s armor collection originally came from the wealthy collector John Woodman Higgins (1874–1961). The son of a major industrialist, he became a steel magnate in Worcester, then known as the “crossroads of New England” due to its status as a key manufacturing hub with access to multiple railroads and a shipping canal. He was fascinated by medieval chivalry and knights.

Higgins’s collection focused most heavily on European armor, but included a number of examples outside of medieval Europe as well. In 1931, he opened the Higgins Armory Museum to the public in order to display his collections. That institution closed in 2013, but WAM acquired the archive in 2014. After 12 years, the Higgins armor is back on display, alongside other pieces the institution collected in the intervening years.

And this time, the world of armored knights has gone global.

Although medieval European armor appears in the galleries, it is presented with equal billing alongside fascinating works from India, Japan, Egypt, Sudan, Ancient Rome, Classical Greece, and many other places across the globe. Indeed, whatever our modern-day associations may be, one of the earliest known depictions of armor is on the Sumerian Standard of Ur (modern Iraq), which dates to around 2550 BCE and is now held by the British Museum. The WAM presentation carries the history of armor and arms into the present. Visitors can even try on a Mandalorian helmet if they want to engage with the fictional future of the art.

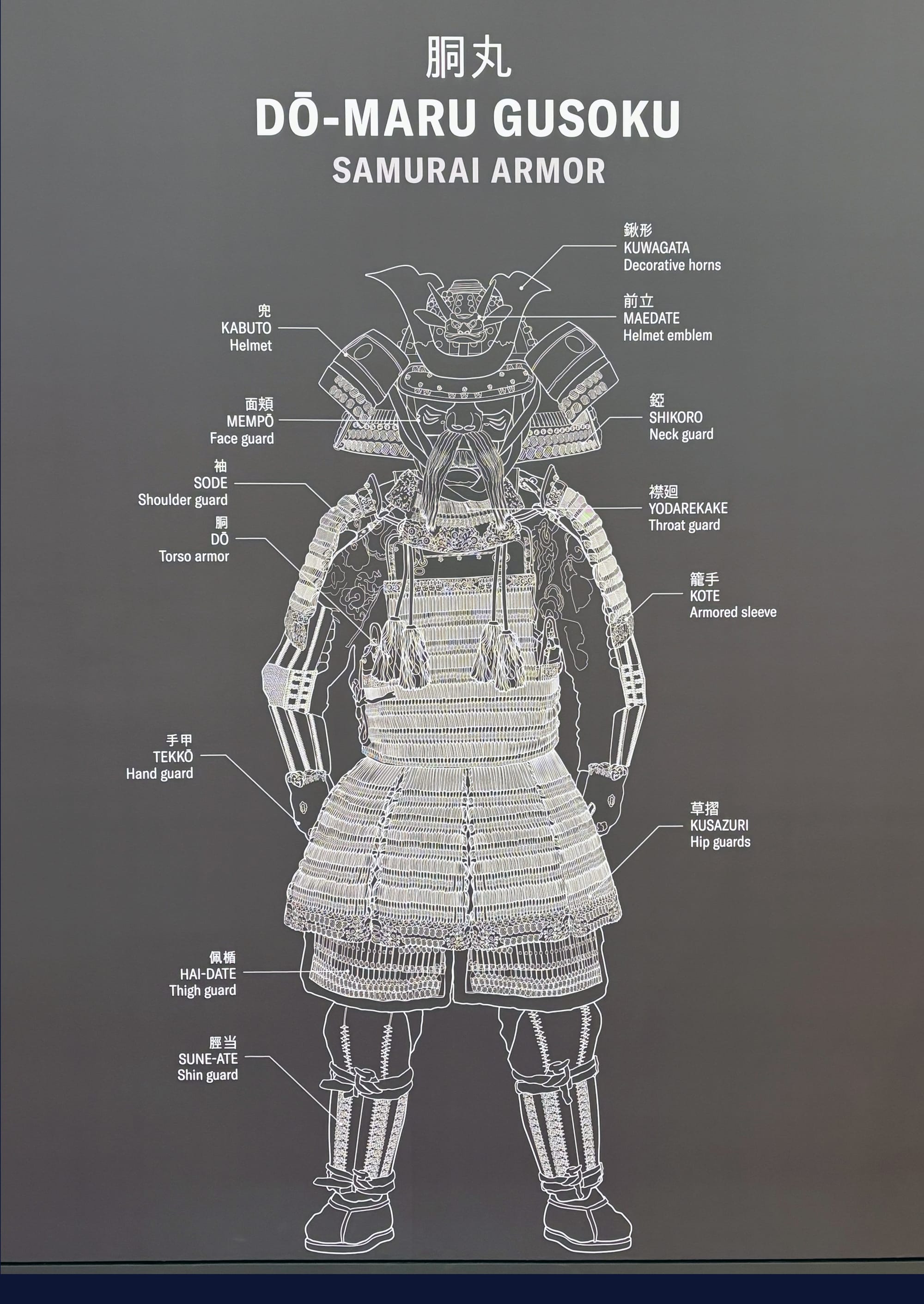

Helpful interactive digital displays allow viewers to explore the labels and items within large glass display cases. They can even peruse the open storage collections that are off view due to space restrictions. Wall diagrams helpfully label suits of armor like the Dō-maru gusoku (samurai armor) and traditional European armor from the Middle Ages. While the gallery walls are packed to the hilt with items and weapons, this lends a sense of cohesion and continuity throughout.

The displays and gallery labels point to the fact that armor was not just for use in battle. Beyond warfare, there was a pageantry surrounding the display of this metal fashion, which was often worn within tournaments and during parades as well. I was impressed by the horse armor and spurs on display for viewers, and even more delighted by the “dog armor” based on a 16th-century medieval European armor suit for a Spanish hunting dog. The Met’s former official armorer (that is a real job!), Leonard Heinrich, designed it for the Higgins Museum in 1943.

It is refreshing to see medieval Europe decentered but still in conversation with both ancient and medieval armor from across the world. As it turns out, the setting of knights’ tales doesn’t just take place in the storied landscapes of the European Middle Ages. They stretch across Eurasia, Africa, Japan, and beyond. The WAM’s galleries don’t remark on this decentering. The galleries instead demonstrate visually that these tales can and should be revised and retold through the diverse arms and armor donned by warriors, resistors, and aristocrats from across the earth — and even those fighting in a galaxy far, far away.