Alexis Rockman Captures Long Island's Flora and Fauna in Dirty Field Drawings

Alexis Rockman is probably known best for his large-scale, vividly colored paintings that encapsulate the threatened state of the natural world, often integrating futuristic imagery.

Alexis Rockman is probably known best for his large-scale, vividly colored paintings that encapsulate the threatened state of the natural world, often integrating futuristic imagery. For two decades, however, he has also created simple, naturalist drawings of individual flora and fauna he observed around the world that capture the diversity of our ecosystems. (The conceptual artist Mark Dion, whom Rockman met in 1988, introduced him to the idea of field research.) From Guyana to Brazil, tar pits in Los Angeles to a fossil field in the Canadian Rockies, the sites Rockman has surveyed have inspired a large number of works he creates using material sourced from those very locations. Last year, the New York City–based artist’s site of choice was close to home: the East End of Long Island. Ninety-three of those works on paper are now on view at the Parrish Art Museum in the exhibition Alexis Rockman: East End Field Drawings, revealing not only the island’s incredible richness of wildlife and vegetation, but also an aspect of Rockman’s work that is strikingly different from his grand paintings.

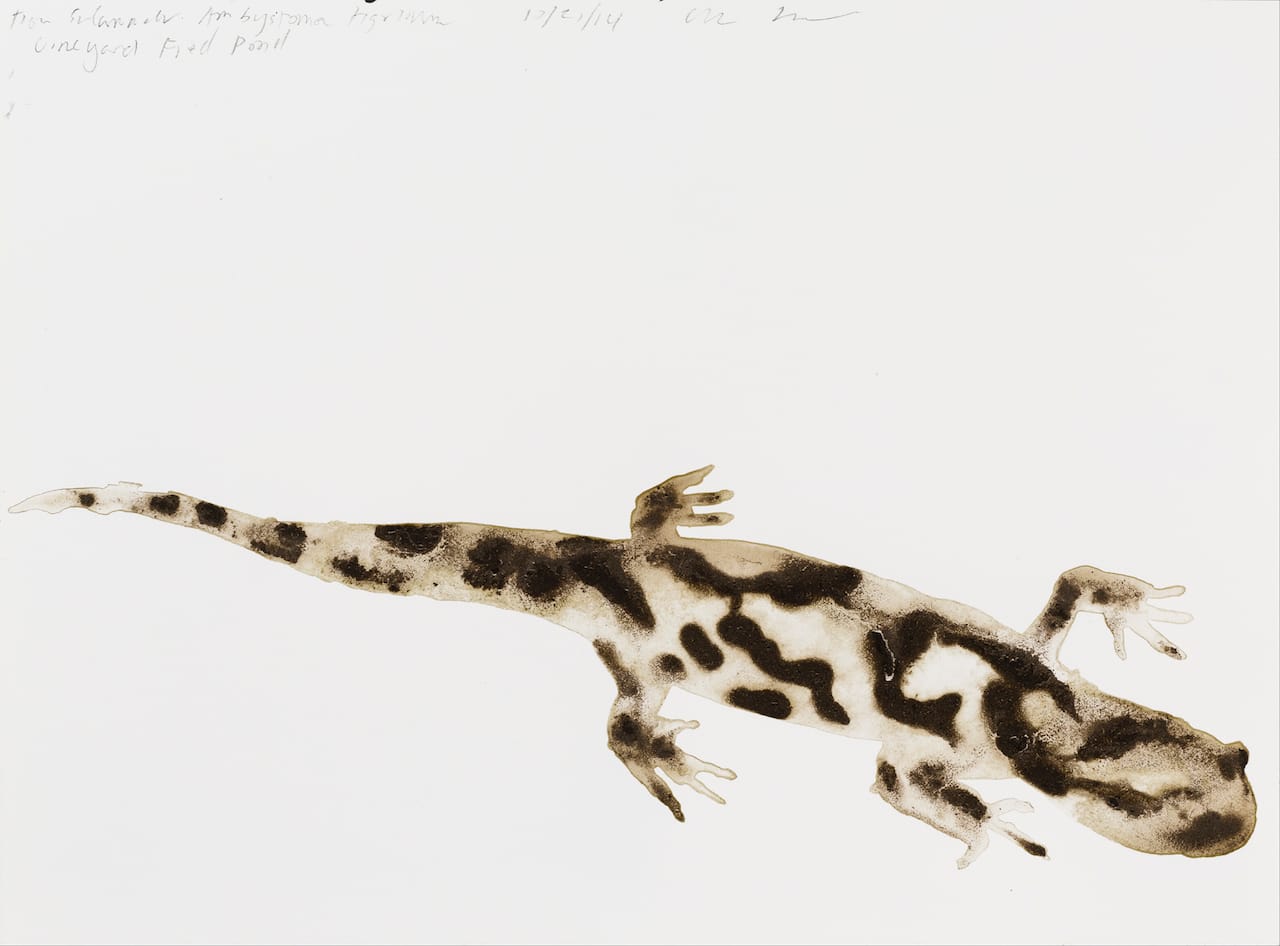

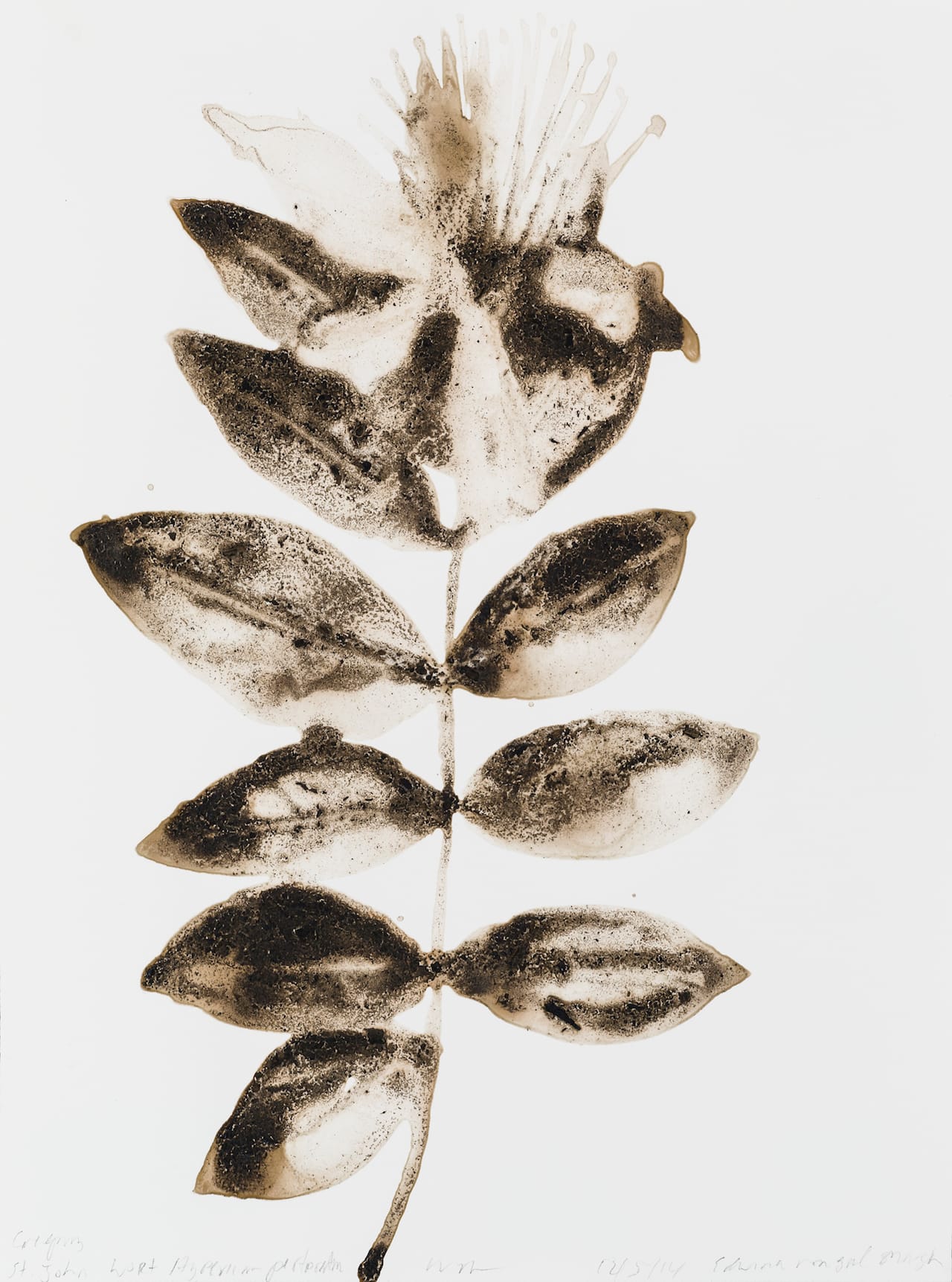

“The Field Drawings are the antithesis of my paintings because they are so immediate,” Rockman says in an interview included in the exhibition catalogue. “They function like pictograms, icons, fossils, or shadows. Because I am using soil or sand as the pigment, the outcome is unpredictable. I never know how the drawing is going to come out.”

Although he considers them field drawings, the works were actually not completed on site but rather rendered in his studio, drawn as reflections of his trips rather than faithful studies of the moment. Rockman worked like a scientist nonetheless, researching the history and fragile ecosystems of the East End and learning about its wildlife and plants. Over the course of seven day trips he explored 18 pockets of the region, noting the birds, plants, fish, and even small insects he saw while gathering sand and soil in Ziploc bags that he carefully labeled with their sites of origin.

At a glance, each work resembles a delicate ink drawing, with faint streaks seeping into dark stains set against stark backgrounds. But the grittiness of the natural world is evident in the works, tying each organism back to its specific location — which he also includes on the paper in light pencil, like a field note. Further blending art and science, Rockman also researched the Latin names of every specimen and included them in the titles of his drawings, emphasizing them as documents of existing creatures. Many of the drawings show rare or invasive species, highlighting an often invisible tension present in these environments. One can only just make out the ghostly petals of a drawing of the threatened pale fringed orchid, for instance, while the rapid-growing mile-a-minute weed stretches across paper in dark, sharply defined lines.

East End Field Drawings also reminds viewers of the incredible diversity of life present on Long Island: great blue herons at Georgica Pond share their habitat with eastern red foxes, wild turkeys, raccoons, brown bats, and opossums; at Kirck Park Beach, Rockman observed jellyfish, harbor seals, sea turtles, and mako shark. Although straightforward and encyclopedic — in contrast to the dense scenes characteristic of the rest of his oeuvre — the field drawings address the same universal concerns about climate change. They capture the environment of this time, while inviting contemplation about the consequences of human activities on the future states of these species.

Alexis Rockman: East End Field Drawings continues at the Parrish Art Museum (279 Montauk Highway, Water Mill, New York) through January 18, 2016.