An Exhibition Goes in Search of Victor Hugo's Artistic Libido

PARIS — With Eros Hugo: Between Modesty and Excess, the Maison Victor Hugo offers up a fervent paradox: how can an author lead a bawdy and risqué lifestyle while handling the subject of sex prudishly in his virtuosic writings?

PARIS — With Eros Hugo: Between Modesty and Excess, the Maison Victor Hugo (once the home of the 19th century French literary master) offers up a fervent paradox: how can an author lead a bawdy and risqué lifestyle while handling the subject of sex prudishly in his virtuosic writings? Curator Vincent Gille may not be able to offer a completely satisfactory explanation of this quandary with this small, elegant, chronologically organized show, but contemplating the question offers stimulating enticements.

A selection of quotations from Victor Hugo’s lesser known written works and correspondence is used as narrative thread throughout this intelligent exhibition. Most of the excerpts are achingly romantic, full of the quiet art of empathy. However, much of the sex depicted in the artworks in their vicinity looks tremendously macho, aggressive, and possibly forced. Throughout, women are depicted as passive or melancholy, contributing to the gloomy mood of the show.

This mood is made even more glum by the energetic bright orange and green gallery walls. Hugo’s often-dramatic drawings are placed here and there in coexistence with other, more accomplished artworks, such as an impressive sculpture of overpowering, frenetic passion by James Pradier, “Satyre et bacchante” (1834), which dominates the large orange gallery, writhing with ferocious debauchery and brutal whimsy. It is rare to encounter a work so captivating that the viewer feels transported through time and immersed in an unfamiliar cultural encounter.

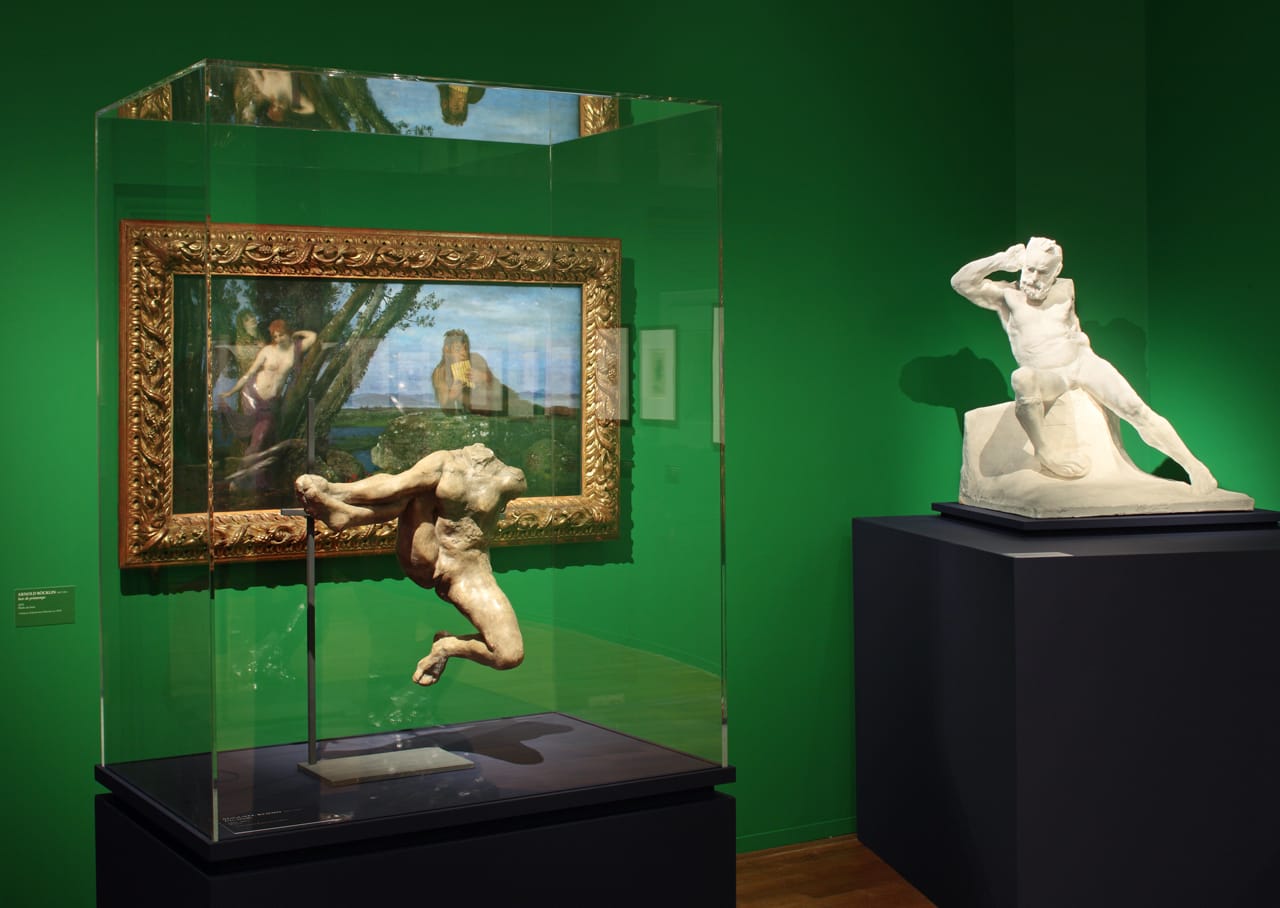

The other scene of eye-popping satyr abduction in the show is an Alexandre Cabanel painting of great turbulence, “Nymphe enlevée par un faune” (1860) — present here in the form of a studio copy by Charles Brun. Originally a historical and genre painter, Cabanel moved to romantic themes after being inspired by Hugo’s collection of poems Les Orientales (1829). Hugo’s poems celebrated liberty, linking the Ancient Greeks with the modern world and embedding freedom of artistic expression into political freedom. Their influence is plainly seen in this and other paintings by Cabanel, like “Albaydé” (1884, not featured here).

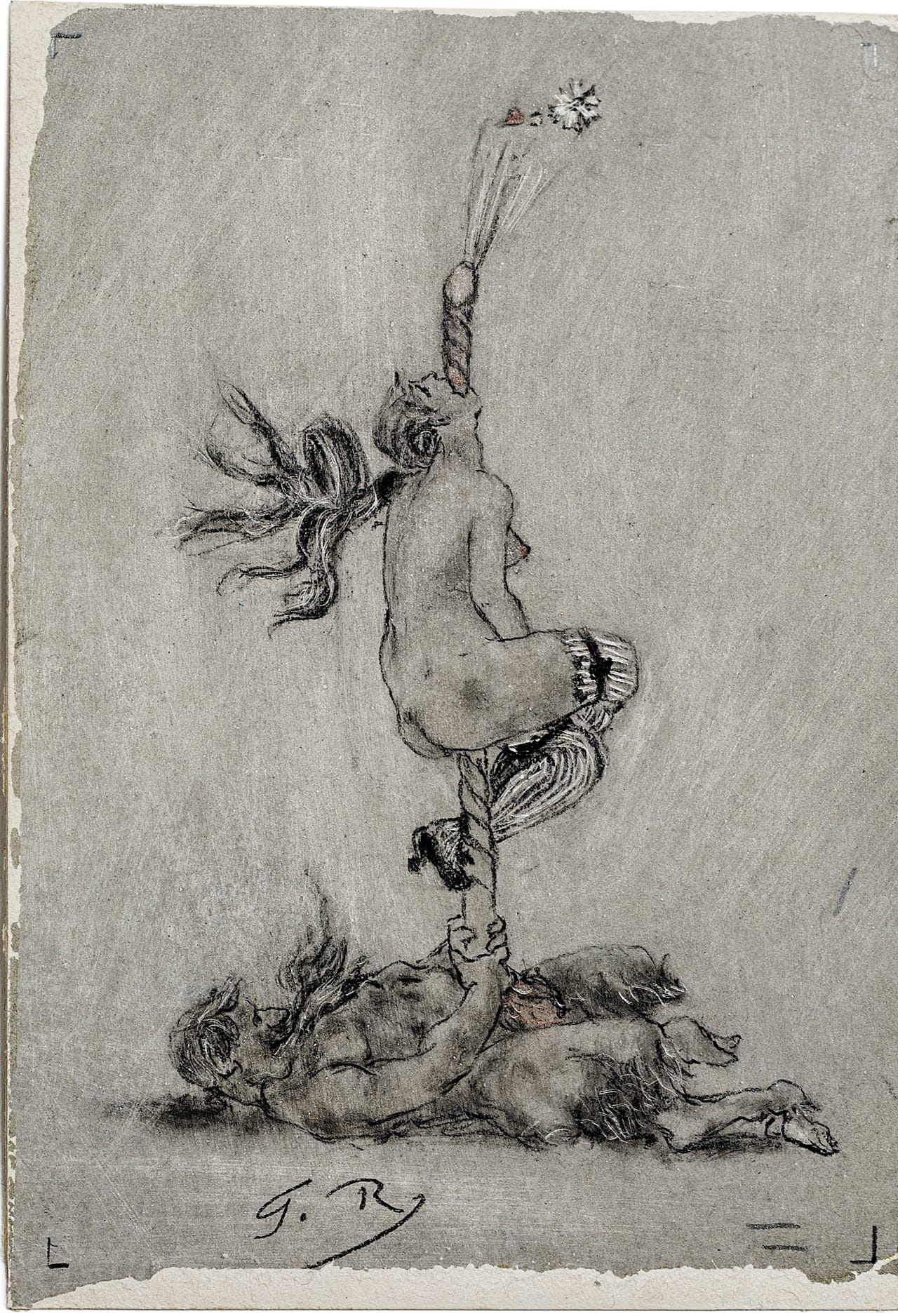

There also is a dastardly drawing by the brilliant Belgian artist Félicien Joseph Victor Rops entitled “La vrille” (late 19th century), which depicts a woman completely impaled on the enormous, threaded phallus of a supine hoofed satyr. It is a disgusting fantasy image, albeit artistically rendered, suggestive of crude sexual violence against women. It comes from the collection of Mony Vibescu, a name that sprung at me like the satyr’s twisted phallus: Prince Mony Vibescu is the fictional character of Guillaume Apollinaire’s 1907 pornographic novel Les Onze Mille Verges (published in English as The Amorous Adventures of Prince Mony Vibescu). Through the character of Mony Vibescu, Apollinaire explored all manner of non-normative sexual activity, from sadism, masochism, scatophilia, and pedophilia, to group sex and homosexuality. The book was highly acclaimed by the Dada and Surrealist poets Louis Aragon and Robert Desnos, and hailed by Pablo Picasso as Apollinaire’s masterpiece.

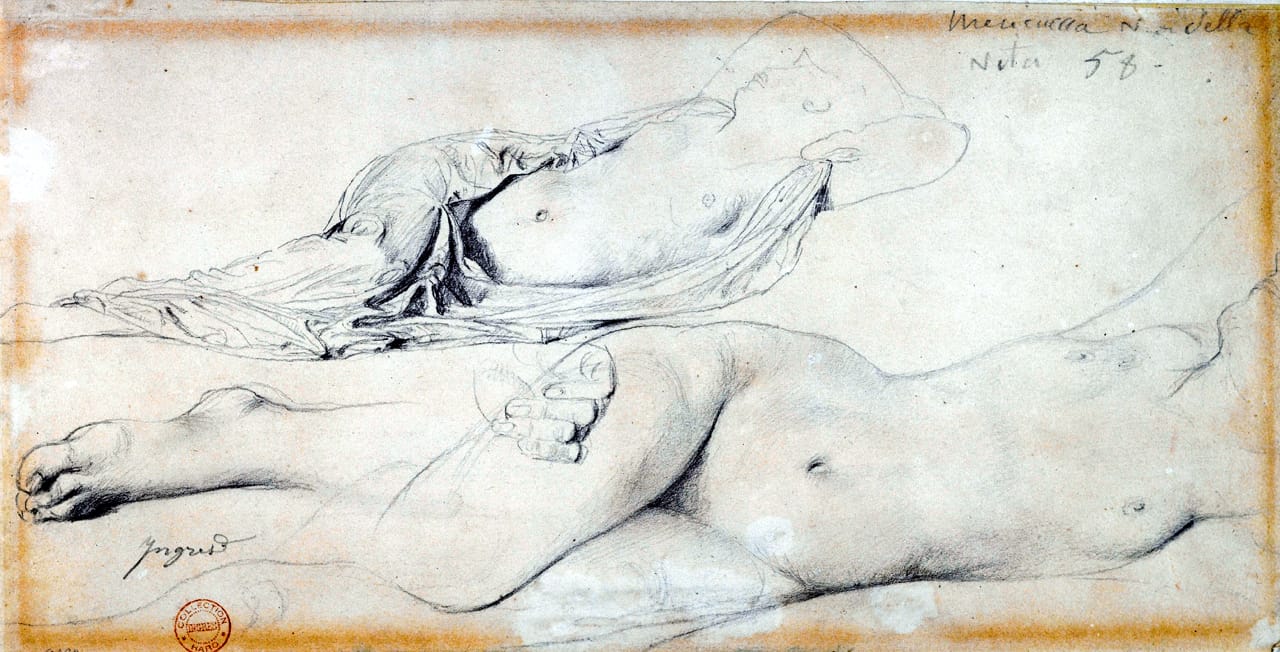

The works by Pradier, Cabanel, and Rops remind us that male sexual desire can be a nasty affair — as if such a reminder were needed. The Swiss Symbolist painter Arnold Böcklin’s masterpiece of lyricism, “Soir de Printemps” (1879), happily softens all that male aggression through the romance of spring seduction, as does Gustave Courbet’s “Les amants dans la campagne” (1844). There are also lovely female nudes, including Hugo’s minimalist “Silhouette de femme vue de face” (late 19th century) and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot’s sultry “Marietta l’odalisque romaine” (1843). Corot’s work is sketchily done in semi-transparent smears of pink ocher, brown, white, and pale green that reveal the original route of the pencil. Hugo’s ink odalisque “Sub clara nuda lucerna” (mid to late 19th century) is also rather accomplished. But it is outshined by the gorgeously sensual and fluid drawing by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, “Étude pour l’Odalisque à l’esclave” (1838), which strangely has a dismembered hand floating around in midst of two reclining nudes rendered with delicate panache.

Floating headless in front of “Soir de Printemps” is Auguste Rodin’s impressively splayed “Iris étude” (1893), on loan from the Musée Rodin. Looking over at her fascinated is another exuberantly exposed Rodin, “Victor Hugo, assis, nu, étude pour le Monument avant” (before 1909) where we encounter an amputated Hugo face to face. The sex paradox is restated here: Why, since Hugo had numerous mistresses (most famously, the actress and courtesan Juliette Drouet) is there almost no overt sexuality described in his books? One of the only two sex scenes in Hugo’s oeuvre is that between the French Roma girl Esméralda and Captain Phoebus in The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. (In the end of the novel — spoiler alert — overt sexual expression is firmly punished, as Phoebus marries Fleur-de-Lys and coldly watches Esméralda’s execution with little remorse.)

I, too, felt little remorse that the paradox of what lies between modesty and excess for Hugo is never resolved here (erotic tenderness in moderation, presumably). The plot goes nowhere. But the scope of the contradictory search is absolutely worth the effort. The exhibition is an intense investigation of Hugo’s hidden artistic libido, assumed but without the details of the subject’s sex life, thus itself an act of artistic projection. Nevertheless, wandering through the show delivers a fine and inventive opportunity to drift in a long-ago time and place where sexual ethics were elegantly strict, at least for the petite bourgeoisie. This bold and utterly first-rate historical exhibition, rich in plot, is just the kind of small-scale jewel that Paris Musées does so well. This public institution, which runs 14 museums in Paris, often crafts dense, ingenious, and even spicy special exhibitions that beg to be seen again and again.

Eros Hugo: Between Modesty and Excess continues at the Maison Victor Hugo (6 Place des Vosges, 4th arrondissement, Paris) through February 21.