Archaeologist Finds Prehistoric European Art World Dominated by Women

Was the majority of prehistoric cave art in southwestern Europe done by women? That's the theory put forth in a study conducted by archeologist Dean Snow, and it's a welcome challenge to the long-held assumption that our ancient artist predecessors were mostly men.

Was the majority of prehistoric cave art in southwestern Europe done by women? That’s the theory put forth in a study conducted by archeologist Dean Snow, and it’s a welcome challenge to the long-held assumption that our ancient artist predecessors were mostly men.

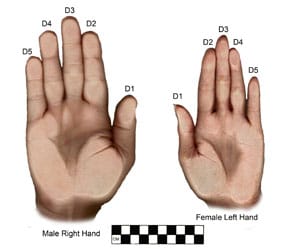

Snow’s study, “Sexual Dimorphism in European Upper Paleolithic Cave Art” (© 2013 Society for American Archaeology, Dean Snow), which was published in the journal American Antiquity and sent by the author to Hyperallergic, focuses on sexual dimorphism (aka the difference in appearance between men and women), using hands as his point of comparison. This makes sense given the plethora of human handprints and stencils in cave art around the world, and Dean was inspired too by the work of a British biologist named John Manning, whose findings offered a way for determining sex in European people based on the ratio of index to ring finger lengths. In women, Manning found, the ratio is, on average, 1; in men, it’s .98.

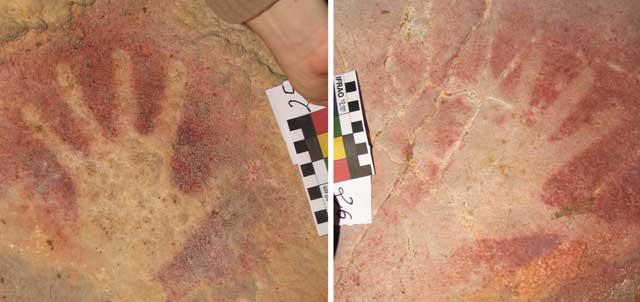

For his experiment, Snow gathered his own samples of handprints from European-descended people and essentially confirmed Manning’s findings, devising a two-step process for determining gender based on handprint. He then took to the caves, namely a handful of Upper Paleolithic ones in France and Spain. Unfortunately, even though the caves “contain a large fraction of the 200–300 hand stencils that are referenced in a wide range of publications,” Snow writes, “only a much smaller number are complete enough or preserved well enough to be potentially measurable.” In the end, he had 32 hand stencils to work with, which he concedes “is smaller than any researcher would prefer” but insists it is nonetheless sufficient.

What Snow found among those 32 samples is that 8 appear to have been done by men, while 24 were likely done by women, making 75% of the sampled cave art the work of women. Not only is that unexpected, but it negates decades of archeological assumptions. As Snow writes:

Most relevant to this article are the traditional assumptions that the Upper Paleolithic parietal art of southwestern Europe was related to hunting and produced by adult or subadult males. As comfortable as these assumptions may have been to modern readers, they are nevertheless untested assumptions. … Our research has shown that at least one common assumption about Upper Paleolithic parietal art can be disproven, namely the assumption that it was produced mainly, if not exclusively, by males.

Virginia Hughes at National Geographic Daily News points out that some experts remain unconvinced, including evolutionary biologist R. Dale Guthrie, whose similar handprint study found that most of the impressions were made by adolescent boys. But Snow remains convinced, not least because his study also found that sexual dimorphism was far more pronounced in the hands of our ancestors, making the results easier to read. He adds that other researchers could use the same technique to carry the inquiry farther but is clear to say that there’s no one-size-fits-all approach; his attempt to determine gender in a Native American sample population, for instance, failed because their hands have developed differently.

Clearly that relegates Snow’s discovery to a very specific group of forebears, but it’s exciting nonetheless. It never hurts to have a reminder that history as we know it is, in reality, a set of common assumptions written by invariably biased humans. The truth could easily be the other way around.